Country summary

Overview

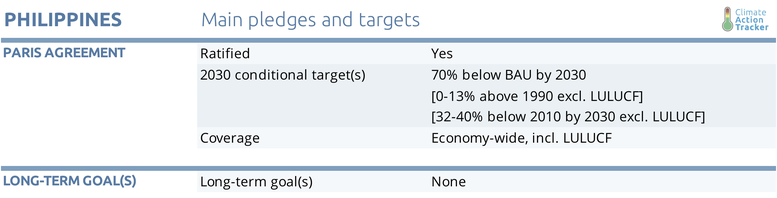

The Philippines’ conditional Paris Agreement 2030 NDC target is rated “2°C compatible” and the Government is currently revising its NDC with view to submitting in 2020. Current policies are not yet on track to meet the NDC target with one of the key issues being the projected growth of coal. In 2015, the Philippines had around 12 GW of coal-fired power capacity under construction or in the pipeline. Since then it has built around 3.2 GW, with another 14.6 GW on the way, triggering concerns over the potential creation of stranded coal assets worth billions.

The Government has acknowledged this with President Duterte recognising in July 2019 the need to “fast-track the development of renewable energy sources and to reduce dependence on traditional energy sources such as coal” aiming to secure the achievement of the Philippines’ long-term vision presented in the AmBisyon Natin 2040. To put the Philippines on a path towards decarbonisation of its energy system and meet sustainable development goals, it needs to combine the goal to decarbonise the energy supply with energy efficiency measures to reduce energy demand. In April 2019, the president signed into law the Energy Efficiency and Conservation (EE&C) Act which established the general governance and strategies to improve energy use in the nation, aiming to reduce overall demand by 24% below BAU by 2040.

However, investments keep flowing in the wrong direction towards coal. Security of its electricity supply is a key issue: The country has experienced a number of power outages earlier in 2019 since the coal-fired installed capacity supplying around 48% of its electricity has not been able to cope with peak demand. The Philippines could increase the reliability of its power system by diversifying the mix towards renewables and storage.

The Philippines power system has been under stress due to the effects of El Niño, which causes warmer weather, and increased electricity demand for air conditioning, and a longer dry season, which lowers hydropower supply and causes issues with the thermal powerplants. Two earthquakes that hit Luzon and Visayas in April 2019 have also caused power outages. Along with the climate and sustainable development imperative to decarbonise, the vulnerability of the system to environmental hazards highlights the need to rethink its current structure.

Increasing renewables rapidly can address these challenges by decentralising and diversifying the Philippine power mix, increasing its resilience. Renewables can enhance the system’s reliability, reduce emissions, while supporting the achievement of the country’s 100% electrification by 2022 target, and advance sustainable development goals. If the Philippines couples low carbon development with energy efficiency goals, it can ensure a more robust power supply for its population.

With the Government currently revising its NDC, hopefully towards higher ambition, including an unconditional target would be an important aspect of scaling up climate action.

While the Philippines’ Paris Agreement target (NDC) is a reduction compared to a business as usual (BAU) pathway, there is no definition of that BAU pathway, rendering the NDC emissions level uncertain. Nor does it quantify future land use emissions, adding to the lack of transparency. In our projections, the CAT assumes that industrial, energy and agricultural emissions are also to be reduced by 70% below a BAU which would result in emissions reverting to 1990 levels by 2030 (excluding LULUCF).

We rate the Philippines’ conditional target of 70% below business as usual (BAU) levels by 2030 “2°C compatible”. The Philippines’ emissions pathway towards 2030, as proposed in its NDC, could be rated “1.5°C Paris Agreement compatible,” if it were unconditional. However, given the conditional nature of the NDC target, we have downgraded it by one category to “2°C compatible” (See “fair share” section). The Philippines’ Climate Change Commission is in the process of revising its NDC that is expected before 2020.

According to our analysis, the Philippines will need to implement additional policies to reach its conditional NDC. Full implementation of the planned “National Renewable Energy Program” and “The Energy Efficiency and Conservation Roadmap” would lower emissions by approximately 10% compared to current policy projections. However, the NDC target is unlikely to be met if all the announced coal-fired power plant capacity (more than 10 GW) were to be built. See Current Policy Projections.

The Philippines’ energy mix relies heavily on coal, which accounted for 26% of total primary energy supply and 34% of electricity generation in 2016. This reliance on coal has caused the emissions intensity of primary energy to increase by 10% since 2010.

In 2015, the Philippines Department of Energy (DOE) announced that more than 10 GW of coal-fired power plant capacity would be constructed by 2025 and released its Coal Roadmap 2017–2040. Despite this, when the Philippines joined the Paris Agreement in 2017, the Secretary of Energy, Alfonso Cusi, stated that ratification would have no effect on these plans.

If all the power plants in the pipeline were to be constructed, the Philippines coal capacity would increase by about 160% above 2016 levels. It would be difficult for the government to achieve its NDC target with all these coal plants. The situation is compounded by the fact that this upswing of development has also increased interest in domestic coal exploration.

Notwithstanding the significant coal pipeline, there has been some regulation of coal-fired electricity as part of the wider Tax Reform for Acceleration and Inclusion (TRAIN) Act, implemented in 2018. The Act raises taxes on coal from USD 0.19 cents in 2017 to USD 2.85 cents per metric tonne in 2020. Even though this measure taxes fossil fuels, and boosts renewable energy cost competitiveness, it is unlikely to incentivise a shift away from coal-fired power generation as major distributors can still pass the higher generation costs on to end consumers.

In 2019 several regulations that support further uptake of renewables are under discussion or have been approved. For example, the Department of Energy (DOE) established a framework for energy storage and off grid power development. Also, improvements in the Green Energy Option Programme, that allows for the user to choose renewable energy suppliers, and the Net-Metering Programme are in the works. Together, they aim to add clarity for end-users, RE suppliers, and network service providers facilitating renewable energy choices and to encourage active participation of consumers in power generation.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter