Country summary

Overview

The Philippines is further advancing the implementation of its ambitious Paris Agreement target, as the first country in the Southeast Asian region to set a moratorium on new coal, and implementing several measures to support renewables. These actions would halt emissions growth and potentially curb the Philippines’ emissions by up to 35% below current policy projections in 2030.

Several typhoons and COVID-19 have put a significant strain on the country and make economic rescue a national priority. However, the ongoing review of ‘Philippine Energy Plan’ provides a chance for the government to accelerate decarbonisation. We rate the Philippines’ conditional 2030 Paris Agreement 2030 target “2°C compatible”, as it would require emissions to decline significantly. Philippines is not yet on track to achieve this target, as emissions increase. The NDC review is an opportunity for the government to solidify the ambition it has outlined in recent announcements.

The CAT expects the Philippines’ emissions to decrease 5-8% in 2020 compared to 2019. The decline has mostly been driven by the sharp reduction in energy demand, especially in the transport sector. The government projects an even sharper decrease in emissions due to a shift away from fossil fuel imports during the pandemic.

The government has focused on the post pandemic economic rescue, proposing few green recovery measures. The ARISE (Accelerated Recovery and Investments Stimulus for the Economy of the Philippines) stimulus package intends to accelerate the recovery by injecting PHL 1.3 trillion (USD 26 billion) into the economy. The main measures target credit guarantees for small businesses, cash aid programs and other social protection measures. The CARE (Corporate Recovery and Tax Incentives for Enterprises) is one exception. It reduces the income taxes of renewable energy-related companies as an attempt to increase ‘green’ investments and jobs.

Other developments indicate that renewables may gain space in the electricity mix in the near future. In November 2020, the Department of Energy announced it will not endorse new coal plants and push “for the transition from fossil fuel-based technology utilisation to cleaner energy sources to ensure more sustainable growth for the country.” Between 8 and 10 GW of the Philippines’ coal-fired power plant pipeline, which is now at 12 GW, could come under the moratorium.

Additionally, the draft ‘Philippine Energy Plan’ (PEP) forecasts a much higher uptake of solar energy, in comparison to the ‘National Energy Renewable Programme.’ A series of reforms are underway to create a more competitive electricity market that favours renewable energy. The establishment of new renewable market rules, under which renewable auctions will take place, and a carve-out clause allowing utilities to curtail coal-fired power generation, will level the national playing field.

However, recent developments in the energy sector remain contradictory. The draft PEP does not include the moratorium on new coal-fired power plants announced in October, and aims to introduce inflexible nuclear power to the power grid. These developments are not in line with President Duterte’s speech in July 2019 when he stated the need to “fast-track the development of renewable energy sources and to reduce dependence on traditional energy sources such as coal.” The review of the PEP, which covers the next two decades, is an important moment to outline a path for the energy sector compatible with the Paris Agreement.

The moratorium on new coal could reduce emissions by 32-35% in 2030 in comparison to our current policy projections. The Philippines is the first among the coal-dominated South East Asian countries to implement such a moratorium. This measure could curb the Philippines’ emissions curve and bring the country much closer to its NDC target. There is a lot of uncertainty, as the full effect of the COVID-19 pandemic or the recovery measures on economic development are still unclear. However, the economic downturn in 2020 will influence emissions for many years. The CAT’s current policy projections show emissions 2-7% lower in 2030 compared to our previous estimate in December 2019.

The government is currently revising its NDC, hopefully towards higher ambition. Including an unconditional target would be an important aspect of scaling up climate action.

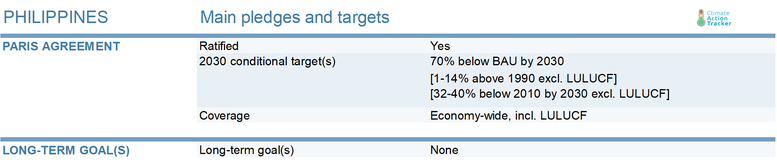

We rate the Philippines’ conditional target of 70% below business as usual (BAU) levels by 2030 “2°C compatible”. The Philippines’ emissions pathway towards 2030, as proposed in its NDC, could be rated “1.5°C Paris Agreement compatible,” if it were unconditional. However, given the conditional nature of the NDC target, we have downgraded it by one category to “2°C compatible.”

According to our analysis, the Philippines will need to implement additional policies to reach its proposed targets. However, the combination of COVID-19’s impact and the coal moratorium could curb the Philippines’ emissions and bring the country much closer to its NDC target.

The Philippines’ electricity mix is projected to remain dependent on coal, but recent developments demonstrate a political shift. Energy Secretary Alfonso Cusi announced on October 27 that new coal-fired power plants will no longer receive permits from the Department of Energy (DOE), putting the country’s massive coal pipeline under question (Ahmed & Brown, 2020; Department of Energy, 2020b).

This measure alone could reductions emissions by roughly 60 MtCO2e in 2030 in comparison to our current policy scenario – equivalent to a 32% to 35% reduction. These emissions reductions were quantified using independent projections that do not necessarily reflect the government plans regarding the uptake of renewable sources, but reflect the maximum impact of the policy – including the possibility of policy spill overs (Ahmed & Brown, 2020).

However, many open questions about the moratorium remain to be clarified. The projects that would fall under the moratorium still needs to be defined. Also, the Philippines needs to align the PEP with its recent announcements. Adding the moratorium to policy documents, such as the PEP and NDC, would show the country’s commitment to push “for the transition from fossil fuel-based technology utilization to cleaner energy sources.”

Meralco, the Philippines’ largest electricity utility, has included a carveout clause in its power purchase agreements in 2020 (Ahmed & Dalusung, 2020). This clause allows for curtailment of coal power amid lower demand caused by the pandemic. These developments, combined, can support a shift away from coal-fired power generation even though major distributors can still pass the higher generation costs on to end consumers (Department of Energy, 2018).

Recent plans to expand the role of gas in the system building terminals to import natural gas do not contribute to the country’s energy independence and would lock in large-scale fossil fuel infrastructure. This would become a barrier to moving to zero emissions power generation (Ahmed, 2020a).

Several regulations supporting further uptake of renewables are under discussion or have been approved. For example, the DOE established a framework for energy storage and off-grid power development (Department of Energy, 2019d, 2019e). The draft circular on Green Energy Tariff Programme (GETP) outlines plants for technology and location-specific renewable auctions. These developments are expected to promote real competition in the country power market (Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, 2020).

The Philippines has begun taking action on energy efficiency; in 2017, the Department of Energy published the Energy Efficiency Roadmap 2017-2040. Overall, the Energy Efficiency Roadmap mandates energy savings equivalent to 24% across energy demand sectors in 2040, compared to the reference energy demand outlook.

The Renewable Energy Act of 2008 aimed to accelerate the exploration, development and utilisation of renewable energy in the Philippines (Congress of the Philippines, 2008). The National Renewable Energy Program (NREP), established in 2011, is the blueprint for the implementation of the Act and seeks to triple the renewable energy capacity level from 4.8 GW in 2010 to 15.3 GW by 2030 (IRENA, 2017).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter