Country summary

Overview

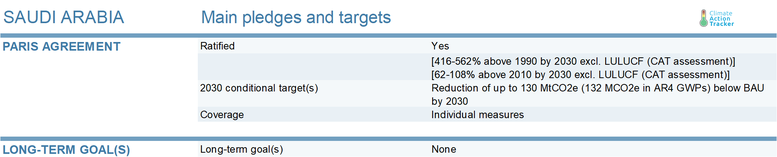

The COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing economic crisis have had a profound impact on Saudi Arabia. With an economy largely dependent on oil export revenues, sinking global oil demand and a freefall in prices have already made a dent in the government budget. As the host of the G20 Summit in November 2020, Saudi Arabia has an important role in shaping the global economic recovery measures. In March 2020, the G20 Leaders pledged to inject USD 5 trillion to the global economy to respond to the financial impacts of the pandemic. Despite “Safeguarding our Planet” and climate mitigation efforts being important agenda points for this year’s summit, Saudi Arabia has reportedly made efforts to censor the discussion around fossil fuel subsidy removal. Saudi Arabia’s domestic climate targets lack in ambition: its 2030 NDC target is “Critically Insufficient”.

We expect Saudi Arabia’s GHG emissions in 2020 to be 3% to 6% lower than in 2019 due to the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic. In May 2020, Saudi Arabia’s crude oil exports declined to six million barrels per day, down from ten million in April. Domestic demand for oil products has also decreased and reached a low point in April (-15% compared to 2019). Tourism to the holy site of Makkah has also been restricted; only a few thousand local visitors were allowed during the Hajj pilgrimage in late July, when usually up to two million pilgrims gather.

The Saudi government has put forward economic recovery measures to respond to the economic crisis brought by the pandemic, but at the same time it has also hiked VAT from 5% to 15% to remediate the loss of revenue from lower oil exports and prices. In April 2020, it also approved USD 240 million (SAR 0.9 billion) worth of additional subsidies to electricity consumers in the commercial, industrial and agriculture sectors. None of the recovery measures address climate change; on the contrary the subsidies provide additional support to an electricity system powered nearly exclusively by fossil fuels.

Saudi Arabia has put few climate policies in place, and diversification away from an oil-based economy has been slow. In early 2019, the government announced a new renewable energy target aiming to achieve 27.3 GW by 2023 and 57.8 GW by 2030, as part of its “Vision 2030” strategy. These new targets are higher than those issued in 2016, which aimed for 9.5 GW of renewable energy by 2023. Progress to date has, however, been slow: only about 0.4 GW of renewable energy capacity had been installed by 2019. According to its “Vision 2030”, Saudi Arabia is also working on a phase-out of fossil fuel subsidies. In December 2017, however, the Saudi government announced it would slow down this fossil fuel subsidy phase-out to enhance the economy.

Another measure of “Vision 2030” was the listing of a small share of the national oil company Saudi Aramco on the stock market in December 2019, making Saudi Aramco the most valuable listed company worldwide. The listing of Saudi Aramco could open the state-owned company to increased international scrutiny, including around climate-related risks. The Climate Accountability Institute recently revealed Saudi Aramco is the company that has contributed by far the most to global carbon dioxide emissions since the 1960s.

The CAT current policy emissions projections for Saudi Arabia are 6–9% lower in 2030 compared to our previous projections in December 2019, due to the impact of the pandemic on emissions. The projected drop in emissions due to the pandemic would make it a good moment for Saudi Arabia to increase ambition on its “Critically Insufficient” climate pledge. There is, however, no indication it will issue an ambitious updated climate commitment in 2020, as called for in the Paris Agreement.

Saudi Arabia’s 2030 climate commitment is highly unclear, due to a lack of data availability, including the absence of any national emissions projections and the fact that Saudi Arabia has not published the baseline corresponding to its Paris Agreement target. The CAT rates Saudi Arabia’s climate commitment “Critically Insufficient” based on available information.

According to our analysis, Saudi Arabia can reach the upper end of its “Critically Insufficient” pledge with post-COVID-19 current policies. Given there is no business as usual (BAU) scenario available linked to the Paris Agreement pledge and uncertainty around the impact of COVID-19, it is however difficult to assess whether Saudi Arabia’s current policies meet the NDC.

Based on our assessment, we expect Saudi Arabia’s emissions to reach a 75–95% increase above 2010 levels in 2030. The policies included here are the 2015 deregulation of energy prices and the transformation of the electricity mix, including the development of renewable energy.

It also appears that Saudi Arabia has decreased its nuclear ambitions. In 2013, Saudi Arabia announced it planned to build 17 GW of nuclear energy by 2032 and later revised this objective to 17 GW by 2040. In September 2019, the newly appointed Minister of Energy stated that Saudi Arabia would “proceed cautiously” with nuclear energy development. There are now tentative plans to build 2.8 GW by 2030.

In 2018, Saudi Arabia signed a memorandum of understanding with SoftBank Group to build 200 GW of solar energy by 2030. In previous assessments, we had taken this project into account in a “planned policies” scenario. In October 2018, reports came out stating the project had been shelved— but the Saudi government refuted this. Yet, there have been no developments since. Given the lack of progress and the new 2030 renewable energy targets announced by the Saudi government in 2019, we deem the likelihood of this project moving ahead low. We have therefore removed this mega-project from our emissions projections as a separate “planned policies” scenario.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter