Policies & action

CAT rates Saudi Arabia’s policies and actions compared to fair share as "Highly Insufficient." This rating indicates that Saudi Arabia’s policies and action in 2030 lead to rising, rather than falling, emissions and are not consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C. If all countries were to follow Saudi Arabia’s approach, warming could reach over 3°C and up to 4°C.

Since our previous assessment, Saudi Arabia’s policies and action rating has changed from "Critically insufficient" to "Highly insufficient" when compared to fair share. Importantly, this adjustment does not indicate any actual improvement in Saudi Arabia's policies compared to our previous assessment. Rather, this reflects a literature update to our fair share (FS) ranges, aligning our equity approaches with international environmental law and excluding studies based solely on cost-effectiveness. We also incorporated additional recent studies to capture the latest research in the field.

Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against modelled domestic pathways and fair share) can be found here.

Policy overview

Saudi Arabia has yet to adopt policies that would substantially reduce its GHG emissions or its reliance on fossil fuels. On the contrary, the CAT projects that its emissions will rise to 819–845 MtCO2e in 2030, a 12–15% increase from 2023 levels. It remains difficult to assess whether Saudi Arabia will reach its 2030 emissions reduction target, given the significant uncertainties surrounding the target itself (see details in the Assumptions section).

Saudi Arabia’s two flagship climate strategies—the Saudi Green Initiative (SGI) and the Middle East Green Initiative (MGI)—lack credible measures to reduce the country’s emissions. Both emphasise afforestation, biodiversity, and other nature-based solutions, but do not address the real driver of emissions: fossil fuel production and consumption. Despite its "Vision 2030" economic diversification plan, launched nearly a decade ago, the Saudi economy remains structurally dependent on fossil fuels, with oil accounting for approximately two-thirds of total budget revenues in 2022.

Oil production continues to undermine climate action. Saudi Aramco, the state-owned oil company, had planned to boost its production capacity to 13 million barrels per day by 2027 through major field expansions. Even though a government directive in early 2024 halted that plan, capacity remains high at 12 million barrels per day, and Aramco has stated that it remains ready to increase output at the government’s request (Attarwala, 2024).

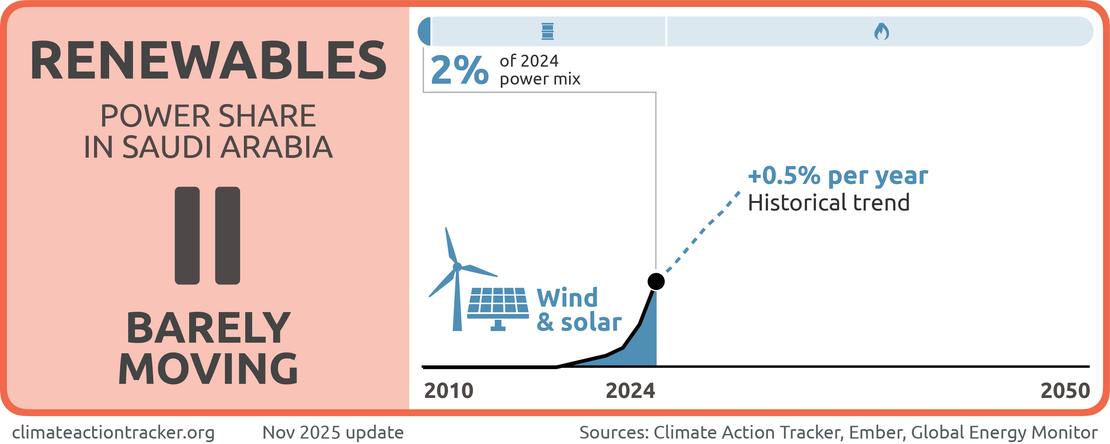

Saudi Arabia’s energy system remains entirely dominated by fossil fuels, which supplied almost 100% of the total energy in 2024 (IEA, 2024). While the government has articulated an ambition to transition towards cleaner energy—most notably, the target of generating 50% of electricity from renewable sources by 2030, a central pillar of both Vision 2030 and the SGI—concrete policy implementation has been sluggish. Despite its vast solar potential, Saudi Arabia had only installed about 4.3 GW of renewable energy capacity as of 2024, accounting for only 2% of its electricity generation.

Achieving its renewable energy target would not drastically cut Saudi Arabia’s emissions but merely stabilise them. Even if the country was to meet its 50% target, the CAT projects that emissions would rise slightly to 756 MtCO2e by 2030, marking a 3% increase above 2023 levels.

Carbon crediting schemes

In 2022, Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund, the Public Investment Fund (PIF), and the Saudi Stock Exchange, Tadawul, set up a voluntary carbon market in the Middle East and North Africa. The first auction in November 2022 offered one million tonnes of international carbon credits (Tamo & Ratcliffe, 2022).

In 2023, the government launched a domestic, government-led GHG crediting mechanism, the Greenhouse Gas Crediting and Offsetting Mechanism. It purportedly enables companies to offset their emissions by buying credits, which are encouraged—but not required—to be aligned with Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. The scheme is voluntary, project-based, and covers all sectors (KAPSARC, 2025).

The establishment of a voluntary carbon market in Saudi Arabia should complement and not distract from—or displace—critically-needed domestic mitigation efforts. Information on how the Kingdom intends to use its carbon crediting scheme remains unclear, which presents major risks that carbon credits with questionable integrity could be used to mask continued high levels of domestic emissions. For more information on the role of voluntary carbon markets under the Paris Agreement and their associated risks (NewClimate Institute & Schneider, 2020).

Power sector

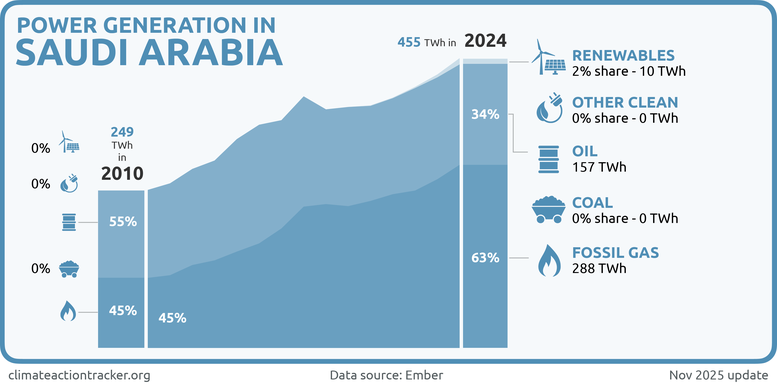

The power sector is the largest source of GHG emissions in Saudi Arabia. The sector is responsible for almost 50% of energy-related CO2 emissions in 2022 (IEA, 2025a). In 2024, Saudi Arabia still produced nearly 100% of its electricity with fossil fuels: approximately 63% from fossil gas and 34% from oil (Ember, 2025).

Despite this heavy reliance on fossil fuels, comprehensive policies to decarbonise the power sector remain limited. While the government has articulated an ambition to transition towards cleaner energy—most notably through a target of generating 50% of electricity from renewable sources by 2030, a central pillar of both Vision 2030 and the Saudi Green Initiative—concrete policy implementation has been slow. Notable policy instruments in place include long-term power purchase agreements (PPAs), competitive auctions, and public-private partnerships.

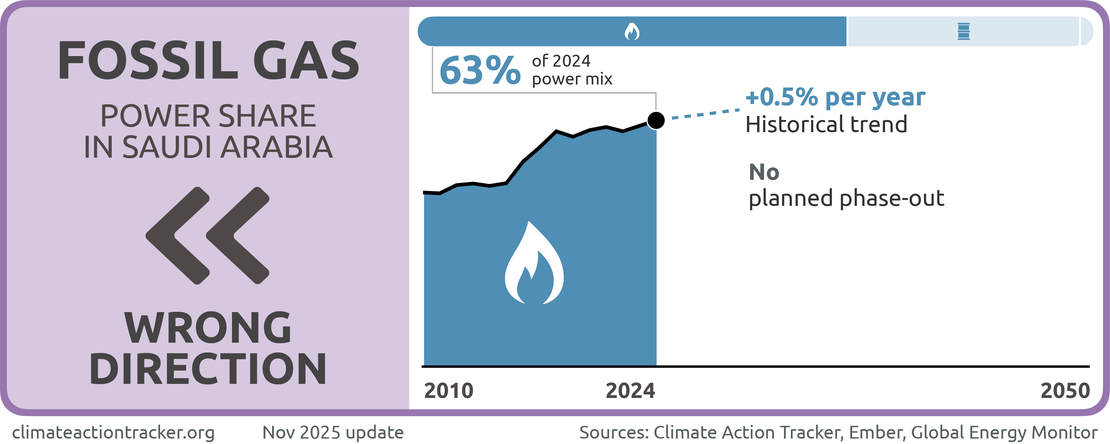

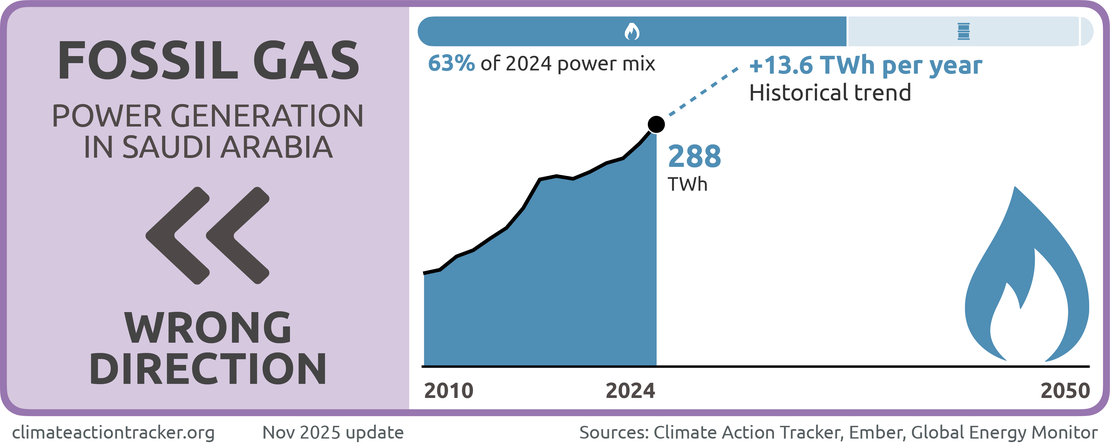

Fossil gas

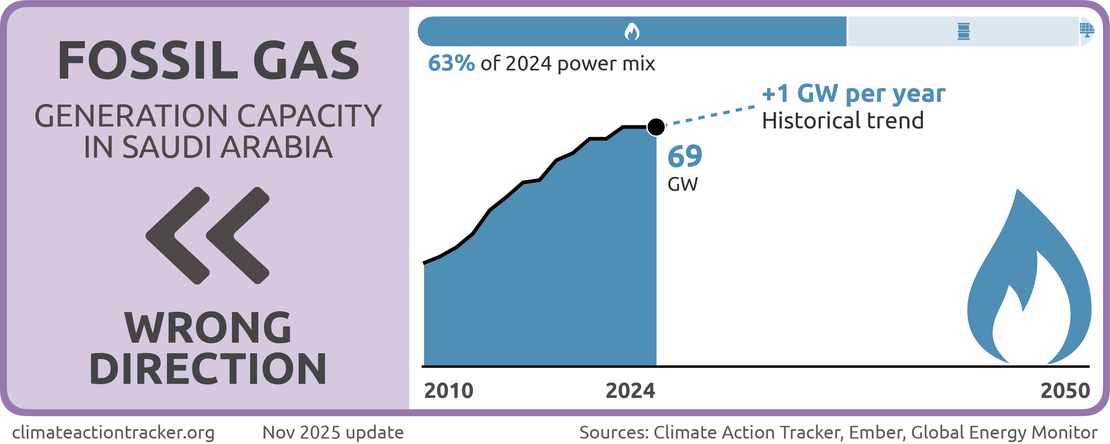

Saudi Arabia is headed in the "Wrong Direction" on fossil gas. The share of gas in the power mix has increased marginally over the last five years, and stands at 63% in 2024. In absolute terms, fossil gas generation has increased from 224 TWh in 2019 to 288 TWh in 2024 (Ember, 2025). Saudi Arabia has no intention of phasing out fossil gas from its power sector. As indicated in its Second Biennial Update Report, the government currently aims for 50% of total electricity to be generated with fossil gas by 2030 (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2024b).

Saudi Arabia is planning to further expand its fossil gas power capacity, with a substantial number of projects in the pipeline. In 2024, generation capacity totalled nearly 70 GW. By 2030, Saudi Arabia plans to have 42 GW of new CCS-ready gas capacity: 9 GW are currently under construction and 21 GW have already been tendered. Four new gas-fired power plants, with a total capacity of 5.6 GW, started operation in 2023 (Enerdata, 2024).

Fossil gas is a fossil fuel and needs to be phased out as part of the global decarbonisation needed to reach the 1.5˚C temperature warming limit. While the pace of action could be slower in developing countries than in wealthier nations, they should still aim to eliminate unabated fossil gas from electricity generation by 2040 (Climate Action Tracker, 2023).

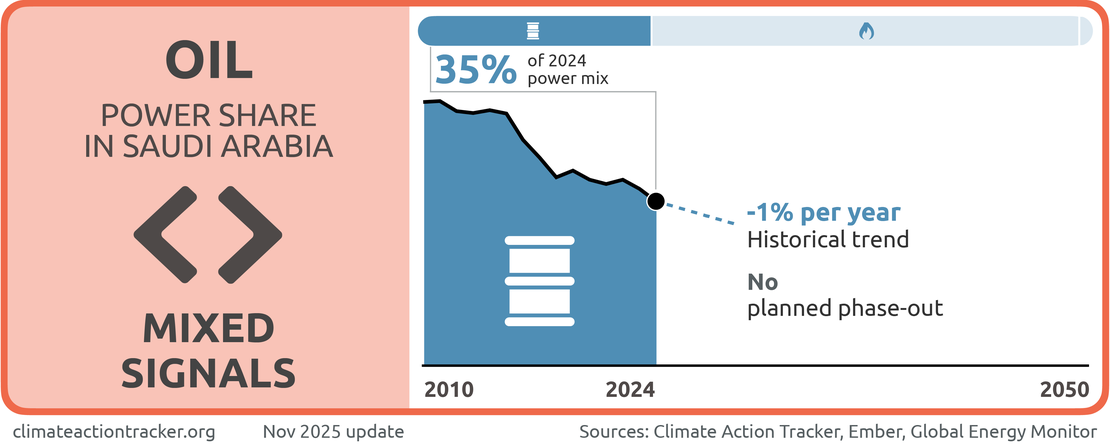

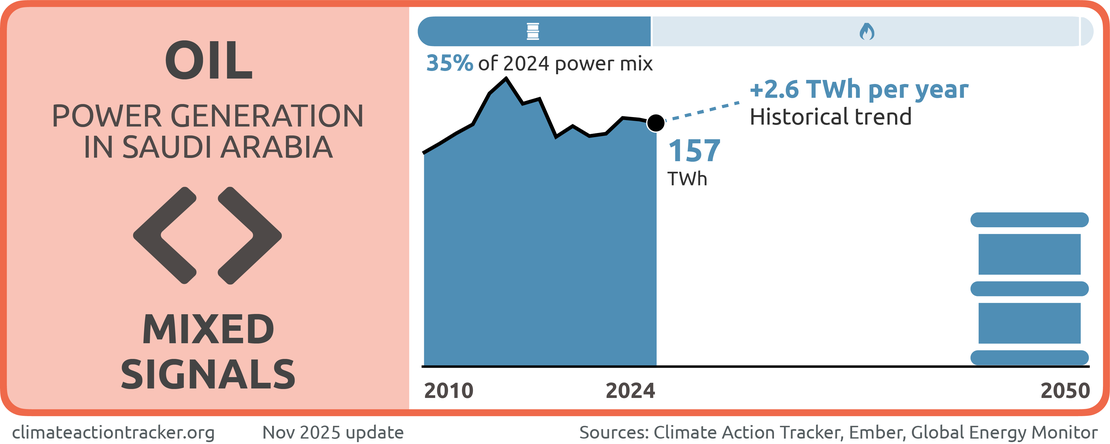

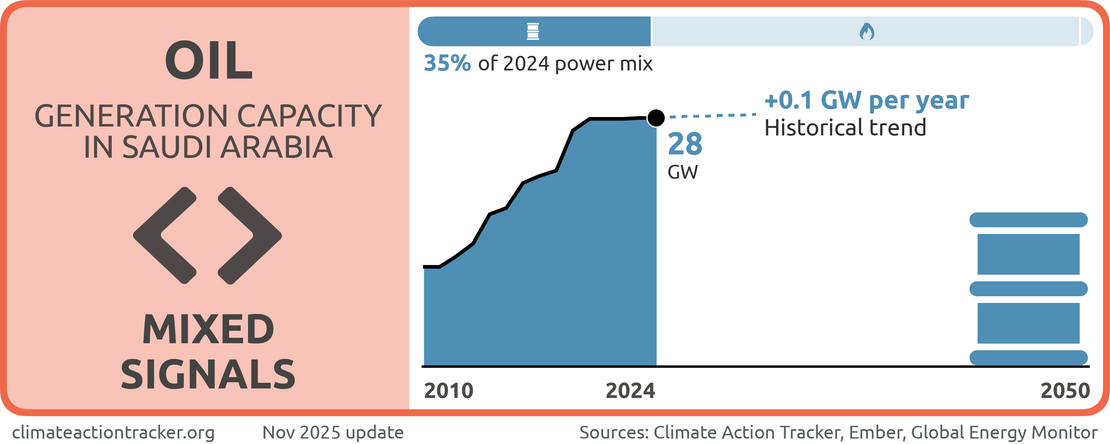

Oil

Saudi Arabia is sending "Mixed signals" on oil. While the government aims to fully phase out oil from its power generation by 2030, it remains completely off track. Although the share of oil in the power mix has decreased over the last five years to 34% in 2024, absolute oil generation has remained largely stagnant (Ember, 2025). Total installed oil-fired generation capacity has also remained relatively stable at approximately 28 GW over the last five years.

Fossil fuel subsidies

In 2022, Saudi Arabia had the G20's highest share of fossil fuel subsidies per capita (Black et al., 2023). Fossil fuel subsidies, both direct and indirect, continue to distort energy prices by keeping oil and fossil gas prices artificially low, discouraging investment in cleaner alternatives.

Saudi Arabia, acknowledging the need for reform in its Vision 2030 strategy, took initial steps to address this issue (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2021d). The government introduced a 5% VAT on fuel and increased the VAT rate for goods and services from 5% to 15%, including those in the hydrocarbons sector (SPA, 2020).

Nonetheless, explicit and implicit fossil fuel subsidies provided by the government increased from USD 141bn in 2019 to USD 253bn in 2022, accounting for 16% of Saudi Arabia’s GDP in 2019, and 27% in 2022 (Black et al., 2023). Driven by soaring energy prices and the demand rebound following the pandemic, these subsidies have primarily benefited the domestic oil sector.

Research shows that adequate pricing of fossil fuels could help cut 36% of global CO2 emissions (Parry & Black, 2021). Setting prices that reflect the true costs of fossil fuels would also further increase the cost-competitiveness of mitigation technologies, such as renewable energy.

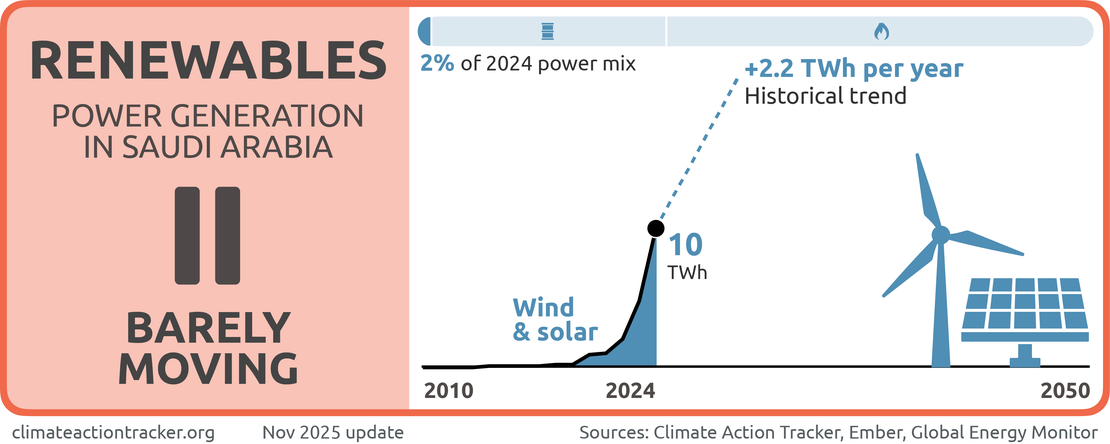

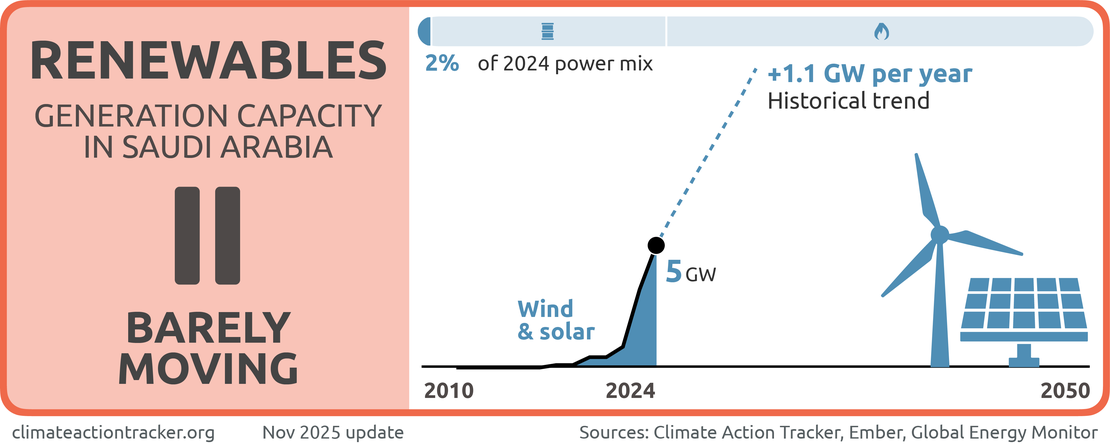

Renewables

The renewable energy sector remains in its infancy in Saudi Arabia. Although renewables-based generation has grown slightly over the past five years, renewables only accounted for 2% of the power mix in 2024 (Ember, 2025). Installed renewable capacity stood at 4.7 GW in 2024. In sharp contrast, Saudi Arabia had 97 GW of oil and gas plants in operation, with an additional 8 GW of fossil plants under construction as of August 2024 (Abdulkareem & Ellaboudy, 2025).

Despite its vast potential, Saudi Arabia’s renewable energy sector has been mired in uncertainty, with ambitious announced plans having largely failed to materialise. The government has put forward multiple renewable energy targets, but made little tangible progress in the last decade. In the first iteration of Vision 2030, which was released in 2016, the government revised its renewable energy target downward to an ‘initial’ 9.5 GW installed capacity by 2023 (Borgmann, 2016). In 2019, the Ministry of Energy released an updated version of the strategy, which aimed to install 27.3 GW of renewable energy capacity by 2023 and 57.8 GW by 2030. The most recent target, presented as part the SGI, aims for 50% of electricity to be generated with renewable energy and 50% with fossil gas in 2030. As part of the SGI, Saudi Arabia also aims to install 100–130 GW of renewable energy capacity by 2030 (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2021d, 2024a, 2025)

Despite some limited progress in the last three years, the pace of renewables deployment in Saudi Arabia remains far too slow to meet the government’s latest 2030 targets, having undershot its 2023 target by almost 25 GW. We evaluate progress in this sector as "Barely Moving."

Hydrogen

Saudi Arabia hopes to position itself as a leader in the global hydrogen market. The government aims to produce four million tonnes of hydrogen by 2030, with at least 50% from green sources. A large green hydrogen production facility is being built in the smart city NEOM (Bell, 2023; Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2023). The plant is expected to be operational in mid-2026 and produce 600 tonnes of green hydrogen per day using both wind and solar energy. Further, the government has announced plans for a green hydrogen facility in Yanbu, which aims to become one of the world's largest facilities with a target of producing 400,000 tonnes of green hydrogen by 2030 (Discover Green Hydrogen, 2025).

The government is pursuing "clean hydrogen" development with a view to diversifying its revenues and becoming less reliant on hydrocarbon exports (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2024b). Considering its strategic location near global shipping lanes and its vast renewable energy potential, Saudi Arabia is also well-positioned to lead the decarbonisation of the maritime sector (KAPSARC, 2023). While it has the potential to become a leader on green hydrogen production, it should, however, first prioritise the rapid scaling-up of renewable capacity to decarbonise the domestic economy, which is currently not pursued at the necessary speed.

Building a robust pipeline of renewable capacity to meet domestic energy needs and eventually compete in the global "green" hydrogen market will be a gradual process, given the low base of renewables in Saudi Arabia. Substantial policy commitments and investments in renewable electricity are critical for Saudi Arabia to position itself as a future leader in "green" hydrogen. Without this shift in the status quo, it will only be able to rely on fossil gas and unproven CCS technologies to produce "blue" or "grey" hydrogen, neither of which are "renewable" nor emission-free.

While hydrogen production from fossil gas tends to be cheaper than green hydrogen in many contexts, it remains expensive; a lot of energy is lost in the conversion process and production is highly susceptible to market price volatility. Gas price fluctuations caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, for example, tripled the cost of grey hydrogen in 2022. Also, emission penalties under carbon pricing are expected to further increase the cost of fossil fuel-derived hydrogen. At the same time, with falling renewable energy costs and technology improvements, green hydrogen—particularly produced with solar PV and wind—could become cost-competitive with fossil fuel-derived hydrogen in the near future (NewClimate Institute, 2023).

Nuclear energy

Saudi Arabia has no nuclear power capacity but intends to build a nuclear power plant in Duwaiheen. Procurement efforts are ongoing in 2025, but information on development plans and timeline is limited. While nuclear electricity generation does not emit CO2, the CAT does not consider nuclear as the solution to the climate crisis due to its risk profile, which includes nuclear accidents and proliferation, high and increasing costs compared to renewables, long construction times, incompatibility with variable supply of electricity from wind and solar, and its vulnerability to heat waves.

Grid infrastructure

In order to meet its 2030 renewable energy target, the government will need to significantly invest in grid infrastructure. The Saudi Electricity Company is spearheading a USD 126bn six-year infrastructure initiatives to improve and expand transmission and distribution grids (James, 2024).

Saudi Arabia is moving ahead with grid interconnection plans with neighbouring countries, focusing on smart grid technologies, which could facilitate a future uptake and integration of renewables (Al-Gahtani, 2024). Saudi Arabia is currently working on grid interconnection project with Iraq, India, Jordan, and Egypt (RE Global, 2023).

Industry

Oil production

Oil extraction has been the backbone of the Saudi economy for decades. Saudi Arabia is the world’s second largest oil producer after the United States and is OPEC’s leading member (Energy Institute, 2025). It produced approximately 11% of the world’s oil in 2022 and holds 17% of proven oil reserves.

While the government has taken small steps to diversify the economy, Saudi Arabia remains highly dependent on hydrocarbon revenue. In 2024, petrochemical commodity exports accounted for 68% of total commodity exports, representing an increase of 2% in value and weight compared to the previous year (SPA, 2025).

Over the past two decades, oil rents, which are the difference between crude oil market prices and production costs, have consistently contributed at least 20% of Saudi’s annual GDP (World Bank, 2021). The dependency between Saudi’s GDP growth and the oil market puts sustainable growth of Saudi Arabia’s economy at risk. Recent geopolitical conflicts have again highlighted the vulnerability of the global oil market to exogenous shocks.

Saudi Arabia does not plan to end investment in new oil production, which is required to hold global warming to 1.5°C (IEA, 2023). While Aramco abandoned its plan to increase oil production capacity to 13 million barrels per day by 2027, this decision appears largely driven by strategic considerations rather than a commitment to phase out fossil fuels. It reflects changes in the global oil market, including slowing demand growth and increased production from non-OPEC countries, particularly the US (Wilson & Tani, 2024).

The government’s current diversification plans do not include scenarios with a decline in global oil consumption in the coming decades, which is required to meet the objectives of the Paris Agreement and to reach net zero CO2 emissions by mid-century (IEA, 2023; IPCC, 2018). Both the "business-as-usual" and the "2030 renewable energy target" scenarios outlined in KAPSARC’s Energy Policy Solutions project hydrocarbon exports to significantly increase until 2050 (see Assumptions section for more information on the KAPSARC scenarios).

At COP28, Saudi Aramco signed the Oil and Gas Decarbonisation Charter (OGDC), a new initiative which aims to "accelerate climate action" in the fossil fuel sector. However, the OGDC only addresses a fraction of relevant emissions from oil and gas production. Although most emissions come from fuel combustion, the initiative solely focuses on reducing emissions within the operations of oil and gas companies, such as during drilling and refining processes. Without a commitment to reducing the extraction and burning of fossil fuels, the charter fails to address the main driver of climate change. So far, none of the signatories have agreed to cut fossil fuel production.

Fossil gas

Saudi Arabia is not a significant gas exporter, but it has domestic gas resources that are used in the power sector, as well as for petrochemical production and desalination. In 2024, production stood at 115bn cubic metres in 2024, which made Saudi Arabia’s gas market the sixth largest in the world. Recently, the government has also invested in gas-to-liquid and LNG projects, but it is deemed unlikely that it will import LNG any time soon (Joseph, 2025).

Carbon capture and storage

Saudi Arabia is betting on carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies to reach its climate goals while sustaining its fossil fuel production and exports. CCS refers to technologies which use engineered methods to capture CO2 from a source and store it geologically - or use it elsewhere. CCS can be applied to a range of different CO2 sources in different sectors. As of 2025, Saudi Arabia only had one operational CCS plant which is used for enhanced oil recovery (EOR) (Global CCS Institute, 2025).

The government has a target to capture and store 44 million tonnes of CO2 annually by 2035. To this end, Saudi Arabia is in the process of building a CCS hub at the industrial complex of Jubail to capture CO2 from fossil gas plants. The hub is expected to be operational from 2027 and the plans are to capture up to nine million tonnes of CO2 per year from three Aramco fossil gas plants (The CCUS Hub, 2023). But given the track record of CCS technology, these planned capture rates are contentious.

CCS technologies are not commercially viable, nor are they proven at scale, despite large public subsidies for research and development globally. Relying on CCS diverts attention and resources away from cost-effective mitigation options. The use of CCS should be limited to industrial applications where there are fewer options to reduce process emissions—not to reduce emissions from the electricity sector where there are cost-effective mitigation alternatives, not least because CCS does not remove 100% of emissions from power plants. Given the levelised cost of renewable energy, it would be far cheaper to increase renewable capacity than deploy CCS.

Saudi Arabia is promoting the concept of a Circular Carbon Economy (CCE) to reduce emissions from oil and gas production (Luomi et al., 2021). This, however, only addresses a fraction of relevant emissions, given that most emissions come from fuel combustion rather than oil and gas extraction and processing. Saudi Arabia’s CCE plans largely rely on the development and deployment of CSS technologies (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2022).

Transport

The transport sector accounted for 29% of total final energy consumption (IEA, 2024), and approximately one quarter of energy-related CO2 emissions in 2022 (IEA, 2025a).

Public transport and railways

The transport sector is dominated by individual, road-based transport but the government has sought to expand its public transportation network in recent years. The King Abdulaziz Public Transport project is a major initiative to modernise transportation in the city of Riyadh. The capital is the second city in Saudi Arabia to have a metro network after the Makkah metro opened in 2010 (Saudi Gazette, 2020). Following a delay, the Riyadh metro system was inaugurated in November 2024 and is nearing completion in 2025 (RCRC, 2025). The Riyadh bus system is designed to complement the metro.

The Saudi government has also taken steps to invest in rail transport. However, while the Haramain High-Speed Railway connecting Makkah and Medina is an electric line, most of Saudi Arabia’s other rail lines—particularly for freight and long-distance passenger travel—are powered by diesel. In 2010, the government launched the Saudi Railway Master Plan, aiming to construct a 9,900-km network by 2040 (OBG, 2020). The first phase, running until 2025, includes constructing and upgrading 5,500 km of tracks for freight and passenger transport, including interlinkages to the wider Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) railway network. The light rail network in the smart city NEOM is complete as of 2024 (Godfrey, 2024).

Electric vehicles

Saudi Arabia has taken steps to increase electric vehicle (EV) uptake, as well as developing its own EV manufacturing industry. As part of its Vision 2030 strategy, the government aims to produce 50,000 EVs annually by 2030 and for 30% of Riyadh’s vehicles to be electric by 2030 (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2021d). The government has invested USD 40bn through the Public Investment Fund (PIF) for local manufacturing and infrastructure (Cita EV, 2025).

In 2022, Saudi Arabia introduced its first domestic EV brand called Ceer, through a joint venture between PIF and Foxxconn, the Taiwanese car manufacturer (Bell & Narayanan, 2023). Manufacturing facilities for Ceer vehicles are under construction, with a planned 175,000-unit output per year. Additionally, Lucid Motors has reached an annual production capacity of 155,000 units. To reduce reliance on the import of components, 15 component manufacturing facilities are under development (Saudi Arabia Transport & Mobility, 2025).

To incentivise EV adoption, several policy instruments are in place, including custom duty exemptions, a zero VAT for EV chargers, fleet adoption incentives, and investments in charging infrastructure. As a result, the number of charging stations increased from 1,200 in 2023 to 5,000 in 2025 – with a target of 50,000 by 2030 in both urban and rural regions (Saudi Arabia Transport & Mobility, 2025).

EV adoption is increasing significantly, albeit at low levels: in 2021, there were 375 EVs on the road. By the end of 2023, the number had reached 12,000 (Cita EV, 2025). Despite the progress made, achieving Saudi Arabia’s 2030 EV target will be challenging. The government will need to accelerate the deployment of charging infrastructure and introduce additional measures to promote greater EV adoption (Oliphant et al., 2022).

Buildings

In 2022, direct energy use in the residential sector was responsible for only 1% of total energy-related emissions (IEA, 2025a). However, when considering indirect emissions, including from electricity use or embodied carbon in building materials, the share is considerably higher. According to some estimates, buildings in Saudi Arabia consume around 80% of total electricity (Felimban et al., 2019). Over 70% of this is used for cooling purposes alone, which is projected to increase as the climate crisis worsens (Sánchez, 2025).

Key challenges include inefficient air conditioning units and inefficient building designs. Consequently, Saudi Arabia is taking steps to improve the energy efficiency in buildings. Through the national Energy Services Company, TARSHID, the government aims to renovate numerous government buildings, public schools, hospitals, and mosques throughout the country (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2021b).

In 2012, the Saudi Energy Efficiency Center (SEEC) launched the Saudi Energy Efficiency Program (SEEP), which targets several sectors of the country’s economy (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2022). Through this program, SEEC has introduced a series of measures in the building sector, including energy efficiency standards and a mandatory labelling programme for insulation materials and air conditioners (ACs). SEEC has also developed guidelines designed to optimise energy consumption in buildings, with a focus on ACs, washing machines, refrigerators, lighting, and heaters. Since their introduction, these standards and guidelines have been further refined and continue to be enforced.

In 2024, the government established a new energy code for new buildings, which includes requirements for building envelopes, AC systems, lighting, and hot water systems (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2024c). More recently, the government's focus has also shifted towards the existing residential buildings stock, but notable policy instruments are still lacking.

Land use and forestry

In 2012, the latest year for which national data is available, the land use and forestry sink only stood at 9 MtCO2e (UNFCCC, 2020), with forests covering a mere 0.5% of Saudi Arabia’s total land area in 2021 (World Bank, 2023). The government has announced plans to plant 450 million trees by 2030 and 10 billion trees over the coming decades as part of the Saudi Green Initiative (SGI). According to the government, this initiative foresees afforestation and land restoration measures to increase the Kingdom’s forestry sink to 200 MtCO2e by 2030. Yet progress is behind schedule: by mid-2025, Saudi Arabia had reportedly only planted 151 million trees (Aboalsaud, 2025).

While reforesting and bolstering the land sector can be highly beneficial to the climate and biodiversity, they risk diverting attention away from the urgent need to phase out fossil fuels and cut GHG emissions. Saudi Arabia’s strong focus on expanding forest sinks could allow emissions in critical sectors like energy and transport to continue rising unchecked. Reducing emissions through tree planting also has inherent limitations. Unlike other sectors, forestry and land use emissions pose unique challenges due to their high variability, measurement complexity, potential reversibility (e.g. forest fires), and high volatility.

Methane

In 2023, the methane sector accounted for 9% of total GHGs, the majority coming from the waste and energy sectors (Gütschow et al., 2025).

At COP26, Saudi Arabia signed the Global Methane Pledge, in which signatories agreed to cut methane emissions in all sectors by 30% globally over the next decade. While its 2021 NDC does not have explicit emission reduction targets for non-CO2 gases, it includes several measures to manage methane emissions, such as the objective to achieve zero flaring in the oil and gas industry (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2021b). However, Saudi Arabia is still planning to ramp-up its oil production capacity towards the end of the decade, making it difficult—if not impossible—to reduce its methane emissions in line with the Global Methane Pledge.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter