Country summary

Assessment

Singapore’s initial reaction to the COVID-19 crisis was swift, announcing funds to cope with the health crisis and reboot the economy in February 2020, with four stimulus packages announced as of June 2020 to support the economy, worth 19% of GDP. If appropriately directed, the financial stimulus funds could provide an opportunity for economic recovery while accelerating plans for a low emissions strategy and a low carbon future. However, there is no sign that Singapore intends to use the funds in this manner and, given the nation has a very weak climate target, rated “Highly insufficient”, it could do well to do so.

The impact of COVID-19 on the economy is projected to reduce emissions in Singapore in 2020, followed by an upward emissions trajectory - based on current policy. Singapore imposed two months of lockdown and began easing restrictions in June. The period of lockdown is projected to shrink GDP in 2020 and reduce activity in emissions intensive sectors.

The CAT’s projections for 2020 and 2030 have changed as a result of COVID-19. Singapore’s emissions are 8% to 12% lower in 2020 and 2030 when factoring in the economic impact of the pandemic. The projected drop in emissions is due to the impact on the economy from Singapore’s lockdown.

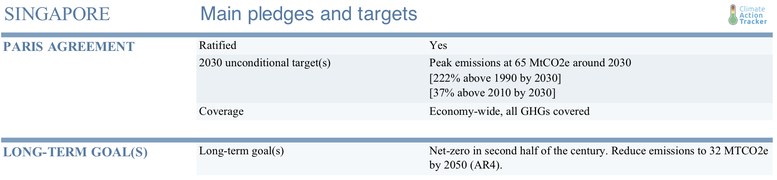

Singapore was already on track to substantially overachieve its very weak 2020 and 2030 targets, without implementing any additional policies. Singapore updated its 2030 target in March 2020, but the updated target is not an increase in climate action, contrary to the Paris Agreement requirement to scale it up. The government converted its emissions-intensity target to an absolute emissions target of 65 MtCO2e for around 2030, which is 28% above 2014 emission levels.

In April, Singapore released a Long Term Low Emissions Development Strategy, aiming to halve emissions from their peak in 2030 to 30 MtCO2e by 2050. The strategy shows a lack of commitment to reaching net-zero emissions, aiming to achieve net-zero “as soon as viable” in the “second half of the century”. Singapore needs to substantially strengthen its 2030 Paris Agreement target, which could form the basis for a more ambitious long-term target.

While renewable energy capacity has expanded, natural gas remains the dominant energy source in the power sector, accounting for 96% of electricity generation. At the Singapore International Energy Week in October 2019, the Minister for Trade and Industry made a speech noting that natural gas would continue to play a role in meeting the country’s energy needs for the next 50 years. At the same time, he unveiled a new 2 GW target for solar energy by 2030.

In 2019, Singapore began implementing a carbon tax for industrial facilities of $5 SGD/tonnes CO2-equivalent (tCO2e) (roughly $3.7 USD/ tCO2e). This low starting price is not high enough to generate the incentives for a large-scale switch to low-carbon generation technologies in the medium term that would set emissions reductions on a trajectory compatible with the Paris Agreement. The carbon tax will remain at $5 SGD/ tonnes CO2 equivalent until 2023. The government has indicated it plans to increase the tax to $10-15 SGD per tonne by 2030. Based on even the most conservative estimates for a 1.5°C compatible pathway, the carbon tax needs to be considerably higher.

In April 2019, the government-controlled Development Bank of Singapore (DBS) announced it would stop funding new coal-fired power stations globally, yet it continues to be involved in several proposed coal power plants in Southeast Asia.

In the transport sector, energy demand and associated emissions are expected to flatten out as a result of multiple measures to promote public transport, modal shifts, and improve the emissions intensity of road transport.

Singapore’s update of its First Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) emissions target is very weak compared to its currently implemented policies. Even without any additional policies, Singapore will overachieve its weak NDC target, while absolute emissions will continue to rise at least until 2030.

We rate Singapore’s updated NDC 2030 target, which is at the same level as the first NDC, “Highly insufficient”, meaning that Singapore’s climate commitments are not in line with any interpretation of a “fair” approach to the former 2°C goal, let alone the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C limit.

As of June 2020, Singapore has announced four stimulus packages worth SGD 92.5 billion, or 19% of GDP, but there is no indication they are aligned with the Paris Agreement or Singapore’s low emissions strategy. There is a lack of clarity of where funds will be channelled making it difficult to assess the impact on low emissions development. The COVID-19 recovery economic stimulus funds, if appropriately directed, offer an unprecedented opportunity for economic recovery through investment support for renewable energy, energy efficiency and research and development in the energy and industry sectors. Emissions in Singapore are dominated by the energy and industry sectors. Energy and transformation industries represent 38% of total emissions, industrial processes 4%, fuel combustion from industry 40%, and fugitives 2% in 2014 (National Environment Agency, 2018). Transport represents 14% of emissions, LULUCF 0.1%, buildings 0.1% and 0.6% of emissions are from waste (National Environment Agency, 2018). Our current policy projections indicate Singapore’s emissions will be 48 - 50 MtCO2e by 2030, similar to the latest recorded historical levels in 2014 of 49 MtCO2e.

The carbon tax, targeting upstream emissions from large emitters, started at 5 SGD/tCO2e from 2019 and will be reviewed by 2023 with the intention of increasing it to between 10 SGD/tCO2e and 15 SGD/tCO2e by 2030. This carbon tax is far too low compared to IPCC estimates for a 1.5°C compatible price. A tax at appropriate level could encourage more renewable energy in place of fossil fuel energy by adding a price for the emitted carbon. However, higher tax levels are likely needed to encourage a significant shift to decarbonising the power sector.

Singapore’s implemented mitigation policies have focused on replacing oil in the electricity generation sector for less carbon intensive fossil fuels, resulting in natural gas representing over 96% of electricity generation in 2016, with around 1% coal and around 3% municipal waste and solar. To diversify its energy mix, Singapore has expanded its solar energy capacity in recent years, going from 26 MW of installed Solar-PV capacity in 2014 to 202 MW in Q2 2019.

Additional policies in the power sector include multiple incentives to increase the share of renewable generation and the expansion of Waste-to-Energy (WTE) capacity. The Public Utilities Board (PUB), Singapore’s National Water Agency, launched a floating solar PV testbed at Tengeh Reservoir in October 2016, and has plans for floating solar projects at reservoirs. The SolarNova programme that forms part of Singapore’s plan to reach 350 MW of installed solar PV capacity by 2020, has accepted three tenders with more to come.

However, Singapore’s energy mix is likely to remain very uniform in the future, resulting in a prolonged dependence on fossil-fuels.

Outside the power generation sector, Singapore’s mitigation efforts almost exclusively consist of measures aimed at further improving energy-efficiency through programmes like Green Mark standards for buildings, green procurement, public transport, fuel efficiency standards, home appliance efficiency standards, industrial energy efficiency, and waste management. However, with a fossil fuel dependent energy mix, the effect of these policies in emissions is limited and does not compensate for the overall increase in energy demand.

Singapore has been moving to promote modal shifts towards public transport and to improve the emissions intensity of road transport. In 2014, the transport sector made up 13.6% of total emissions.

Singapore’s plans to increase the length of the rail network from 230 km in 2019 to about 360 km by 2030 will enable eight in ten households to be within a ten-minute walk of a train station. Singapore’s target for the public transport modal share during morning and evening peak hours is to reach 70% by 2020 and 75% by 2030, up from 59% in 2008 and 67% in 2017.

Since February 2018, the growth of private vehicles has been effectively capped, when the permissible growth rate of private vehicle population was reduced from 0.25% to 0%.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter