Country summary

Overview

The South African government finally approved its Integrated Resource Plan (IRP2019) in October 2019, confirming the trend change in power sector planning indicated in the draft for comment from August 2018. The plan reduces the role of coal compared to previous planning and increases the adoption of renewables and gas. Unlike earlier drafts, the IRP2019 proposes extending the operational lifetime of South Africa’s sole nuclear power plant by 20 years, up to 2044.

The final plan marks a major shift in energy policy, which is remarkable for a coal-dominated country like South Africa. It aims to decommission over 35 GW (of 42 GW currently operating) of coal-fired power capacity from state-owned coal and utility giant Eskom by 2050.

However, it would still see South Africa complete nearly 6 GW of costly coal capacity currently under construction and commission another 1.5 GW of new coal capacity by 2030. IRP2019 includes a detailed phase-out plan for coal-fired power plants, which, despite improvements to earlier plans, still shows that substantial amounts of coal capacity will run beyond the year 2050. For Paris-compatibility, coal must be phased out globally, at the very latest by 2040.

The plan also proposes a significant increase in renewables-based generation from wind and solar as well as gas-based generation capacity by 2030 (an additional 15.8 GW for wind, 7.4 GW for solar and 2.5 GW for gas by 2030), with no further new nuclear capacity being procured.

Implementing the IRP2019 will enable South Africa to achieve its 2030 NDC target. However, we rate South Africa’s NDC target as “Highly Insufficient” based on the upper end of the NDC range. In this context, South Africa should consider revising its target downward for 2030 to be resubmitted to the UNFCCC as part of the Paris Agreement’s ambition raising cycle of 2020.

To be in line with the Paris Agreement goals, South Africa would need to adopt more ambitious actions by 2050 beyond the IRP2019, such as even further increasing renewable energy capacity by 2030 and beyond, fully phasing out coal-fired power generation by latest 2040, and substantially limiting natural gas use.

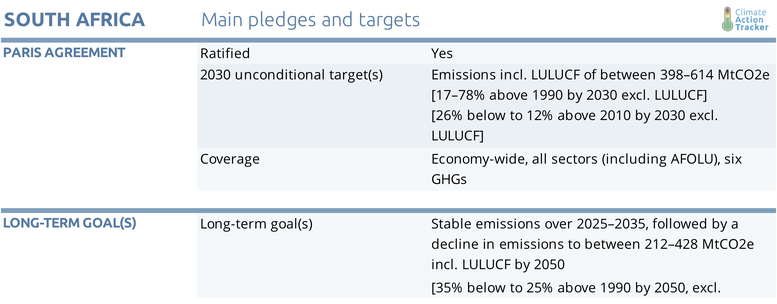

Although South Africa is one of the few countries that has put forward absolute emissions targets in their NDC, we still rate this target “Highly Insufficient”.

Our analysis shows that under its currently implemented policies and continued low economic growth, South Africa will overachieve the less ambitious end of its emission reduction targets throughout all years. Its current policy projections fall within the “peak, plateau, decline” pathway that the South African government defined as its NDC.

The CAT’s projections show South Africa’s emissions trajectory under its implemented policies in 2020 and 2030 is expected to decrease compared to today, but end up at 50% and 33% to 30%, respectively, above 1990 levels excluding LULUCF. If South Africa’s economy were to grow at a higher rate, emissions until 2030 may end up higher than currently expected. If the current trends continue, South Africa has already reached a peak in emissions.

In the first quarter of 2019, South Africa experienced several instances of rolling blackouts instituted by Eskom, the state-owned grid operator and owner of most of the nation’s coal-fired power plants. These recent operational problems add to overall concerns on future reliability and sustainability of South Africa’s electricity supply.

Uncertainty around Eskom’s financial solvency also remains a contributing factor to overall planning uncertainty and ongoing delays in progress on renewable capacity extension. In this context, President Ramaphosa appointed an Eskom Sustainability Task Team in December 2018 to provide recommendations to address Eskom’s many operational, structural, and technical challenges.

The South African government finally implemented a carbon tax in June 2019 after two years of consultations, although its immediate impact is likely to be limited given there are tax exemptions for up to 95% of emissions during the first phase until 2022.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter