Policies & action

We rate South Africa’s current policies and actions as “Insufficient”. The “Insufficient” rating indicates that South Africa’s climate policies and action in 2030 need substantial improvements to be consistent with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C temperature limit. If all countries were to follow South Africa’s approach, warming would reach over 2°C and up to 3°C.

Under these current policies, South Africa will not achieve the necessary emissions reductions needed to meet its NDC target range for 2030. If considering South Africa’s planned - but not yet implemented - policies, our rating of policies and actions would improve to “1.5°C compatible”. The stringent implementation of proposed economy-wide and sector-specific policy measures would also enable South Africa to achieve at least the top end of its NDC range.

Policy overview

South Africa is undergoing a period of political change. In May 2024, the country voted to remove the African National Congress (ANC) from majority rule for the first time since the end of apartheid rule in 1994. A coalition government subsequently formed between the ANC, the Democratic Alliance party and smaller parties. The new government assumes power in difficult circumstances (BBC News, 2024). In late 2024, South Africa’s unemployment rate was estimated to be 32% and structural issues with the country's infrastructure continue to present major obstacles for economic development and the energy transition (FRED Economic data, 2024; Rose, 2024). Interest paid on debt also continues to rise as a share of government spending, reaching 15% of total public expenditure in 2023 (Department of Statistics, 2024). Despite these challenges, South Africa continues to pursue GHG reduction and has meaningfully progressed several energy transition policies in 2024.

Using the latest available emissions data, the CAT estimates a decline of close to 3% in emissions between 2021 and 2022. This reverses the growth observed between 2020 and 2021 and means South Africa’s latest post-COVID emissions total is almost 9% lower than the pre-pandemic 2019 total figure.

The CAT estimates South Africa’s emissions under current policies are on track to reach 445–481 MtCO2e excluding LULUCF by 2030, equivalent to 10–17% below 2010 levels excluding LULUCF. Under these current policy projections, South Africa’s emission levels in 2030 will be above the upper bound of the updated NDC target range for the same year (around 8–44 MtCO2e higher).

The range of our latest projections have decreased compared to our previous projection from October 2023. This is due to a downward revision of historical data using more recent government reported inventory data for 2007 to 2020 and updated estimates of 2022 from PRIMAP as explained in the Assumptions section (DFFE, 2023; Gütschow & Pflüger, 2023b).

We further estimate that emission levels could decrease to as low as 395 MtCO2e excluding LULUCF by 2030 if South Africa were to implement its planned policies, including the expansion plans for the renewable electricity procurement, the accelerated switch to low-carbon mode of transport, energy efficiency measures, and a strengthened carbon tax. Under these planned policies projections, South Africa would fall under the upper bound of its 2030 NDC target range. These findings emphasise the emissions reduction potential of a stringent implementation of proposed economy-wide and sector-specific policy measures.

Most of South Africa’s active GHG mitigation policies target the power sector, which is the single largest source of emissions in the country, accounting for over 40% of total emissions in 2022 (South African Government, 2024b). Significant changes are occurring in the sector. The government is attempting to shift the sector in a more market-oriented direction and is targeting increased generation capacity across fossil and renewable sources.

Cross-sectoral policies

The key cross-sectoral polices in South Africa are the recently adopted Climate Change Act and a carbon tax, enacted in 2019. In addition, South Africa is implementing a Just Energy Transition Partnership Investment Plan with the support of several developed countries and private donors.

In July 2024, South Africa’s President Ramaphosa signed the Climate Change Bill into law (South African Government, 2024c). The Climate Change Act represents a significant step forward for South Africa’s governance of climate change mitigation. Under the legislation, the Minister responsible for Environmental Affairs together with the Ministerial Committee on Climate Change must set sectoral emission targets for each GHG emitting sector in line with the national emission target every five years.

Carbon budgets will also be allocated to significant GHG emitting companies to place a cap on emissions and make it mandatory for companies to constrain their emissions. Furthermore, the law requires the responsible persons to implement relevant policies and measures, monitor their effectiveness and report on progress annually to the South African Presidency. The mitigation plans must be made public, inviting scrutiny from third parties. While the Climate Change Act strengthens governance of South Africa’s GHG mitigation efforts, it has been criticized for failing to prescribe penalties for excess sectoral or company emissions. Instead, the government intends to amend the Climate Tax Act so that companies which exceed their carbon budgets will pay a higher rate of carbon tax on excess emissions, effectively allowing emitters to “pay to pollute” (Centre for Environmental Rights, 2023). The effectiveness of the legislation will thus rely on the excess emissions fee being sufficiently penalising to incentivise mitigation efforts.

The importance of South Africa’s carbon tax, adopted in February 2019, is strengthened through this interlinkage with the Climate Change Act. The carbon tax in its present form covers fossil fuel combustion emissions, industrial processes and product use emissions, and fugitive emissions such as those from coal mining (Climate Home News, 2019; Reuters, 2019). The carbon tax rates were last adjusted in 2022 and as of 2025 are applied at a headline rate of R 236/tCO2e (approximately USD 12.50/tCO2e). The government further plans to reach a carbon price of USD 30/tCO2e by 2030 and USD 120/tCO2e by 2050 (National Treasury, 2024). The current structure of the tax allows for substantial reductions in the headline rate due to tax free allocations of 60 to 95% of total GHG emissions of affected firms and the use of carbon offsets to reduce the tax bill. Previous analysis found that the carbon tax does not effectively contribute to emission reductions given the low levy, generous basic allowance and other available exemptions (Szabo, 2021).

South Africa is currently in the process of designing a more stringent second phase of the carbon tax. The South African Treasury published proposed changes to the carbon tax rules in November 2024 with the consultation closing in December 2024. The proposed changes include reducing the tax-free allowance by 10 percentage points in 2026, from 60% to 50% of emissions, and a further 10 percentage points reduction phased in over the 2027 to 2030 period. The allowed use of carbon offsets to reduce the tax bill will simultaneously increase to from 5% of total emissions in 2025 to 20% of total emissions in 2026 and remain at 20% to 2030. Combined, these changes will lead to an estimated effective tax rate of just 69–116 R/tCO2e by 2030 (around 3.7–6.2 USD/tCO2e) (National Treasury, 2024). Thus, the proposals for the second phase of the carbon tax retain generous reductions in headline tax exposure. The carbon tax is therefore unlikely to significantly increase incentives for emission reductions. The South African government has proposed a higher rate of 640 R/tCO2e for emissions exceeding allocated carbon budgets under the Climate Change Act. While this would represent a significant strengthening of incentives, the rate which will be applied to excess emissions and how it will interact with reductions is yet to be finalised. A sufficiently stringent rate is necessary to avoid negating the effectiveness of the Climate Change Act.

Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP)

At COP26, South Africa, France, Germany, UK, USA and the EU made a political declaration to establish a long-term partnership to support South Africa’s pathway to low-emissions and climate resilient development.

The partners resolved to mobilise an initial USD 8.5bn in grants, concessional loans, guarantees, private investments, and technical support in the first five-year period between 2023-2027 to accelerate the decarbonisation of South Africa’s electricity system to achieve the most ambitious NDC target, support a just transition that protects vulnerable workers and communities, and support green industrialisation, including green hydrogen and low-carbon transport technologies (Farand, 2021; Government of South Africa, 2021d).

The South African Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) builds on a country-led, donor-supported process by the South African government, putting a distinct focus on a just transition, including retraining and supporting coal workers. Since the announcement of the partnership, additional international donors, including the World Bank, the African Development Bank and CIF, have increased the available funding from USD 8.5bn to USD 13.8bn. Of the pledged funds, 7% is in the form of grants, with the remaining funds allocated by way of concessional loans and commercial investments (CIF, 2025; World Bank, 2023). Unfortunately, in early 2025, the USA decided to withdraw from the partnership and rescind its committed funding. However, the withdrawal of the USA still leaves South Africa with USD 12.8bn in funding and the government is actively seeking new partnerships (South African Government, 2025b).

Meanwhile, implementation of JET-P projects has commenced. The South African government published an implementation plan in November 2023, with 2024 being the first year of active implementation (South African Government, 2024f). The Just Energy Transition Implementation Plan (JET-IP) outlines the allocation of funds across six portfolios: Electricity, Mpumalanga Just Transition, Municipalities, New energy vehicles, Green Hydrogen, and Skills. The cross-sectoral investment plan notes that the three priority areas of focus are electricity, new energy vehicles and green hydrogen. The bulk of the funds are intended to be allocated to the electricity sector, with 48% of total identified funding requirements planned for this sector. The implementation plan identifies total funding requirements of USD 98bn for full implementation of the plan (South African Government, 2023c). Substantial additional funds must therefore be leveraged from public and private sector sources to implement all planned projects by 2028.

Despite South Africa’s energy crisis and change in government, implementation progress on the JET-IP has progressed. The government publishes data on the grant funded projects of the JET-IP and, as of Q3 2024, just under USD 388mn has reached implementation stage projects (South African Government, 2025a). Granular data on the non-grant forms of finance in the partnership is not readily available but the European Commission reported that USD 2bn had been spent on the JET-IP as of early 2025 (European Commission, 2025). Overall, the evolution of the JET-P process in South Africa reflects the challenging nature of sustaining partnerships between varied countries and implementing long-term plans without the certainty of commitment from key partners. The success of South Africa’s implementation will hinge on sufficient funding from diverse sources remaining available through the implementation period, so that South Africa can sustain the internal resources needed to drive delivery.

Power sector

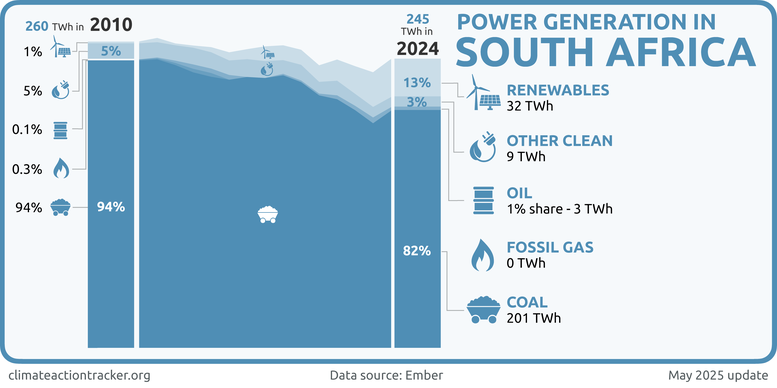

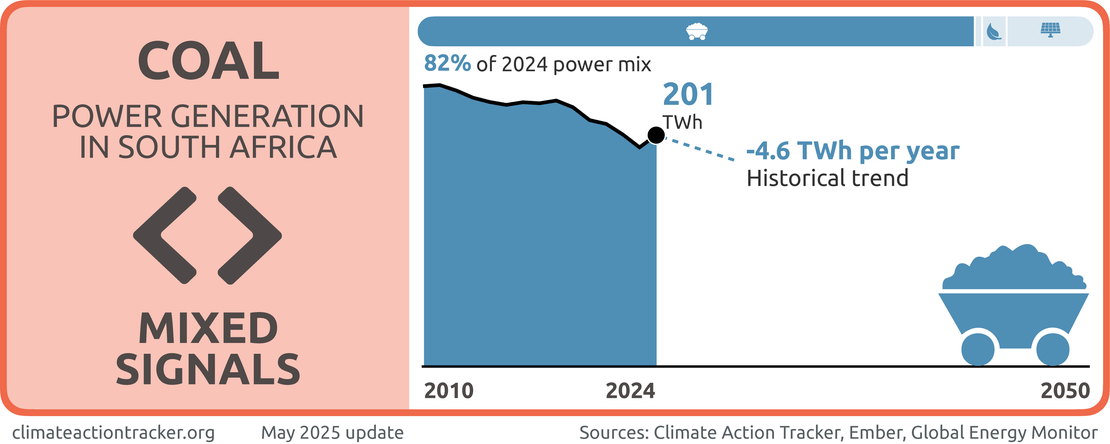

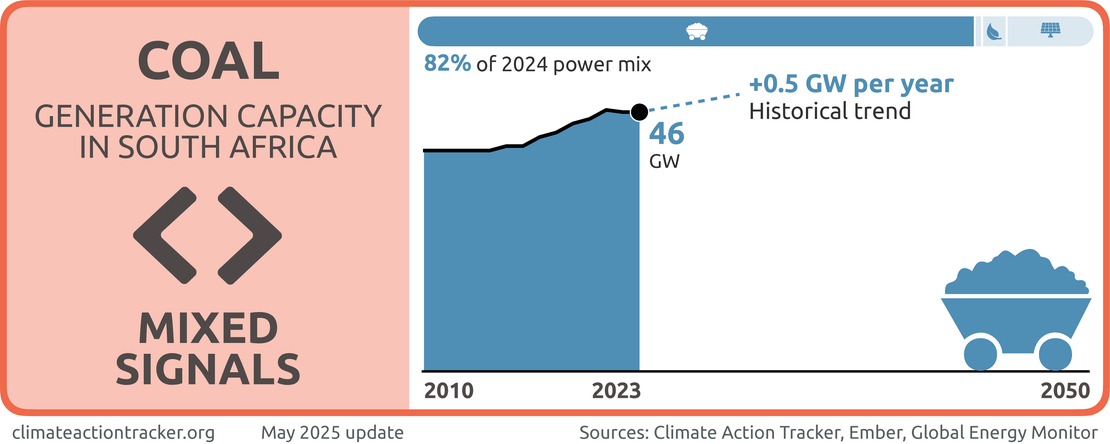

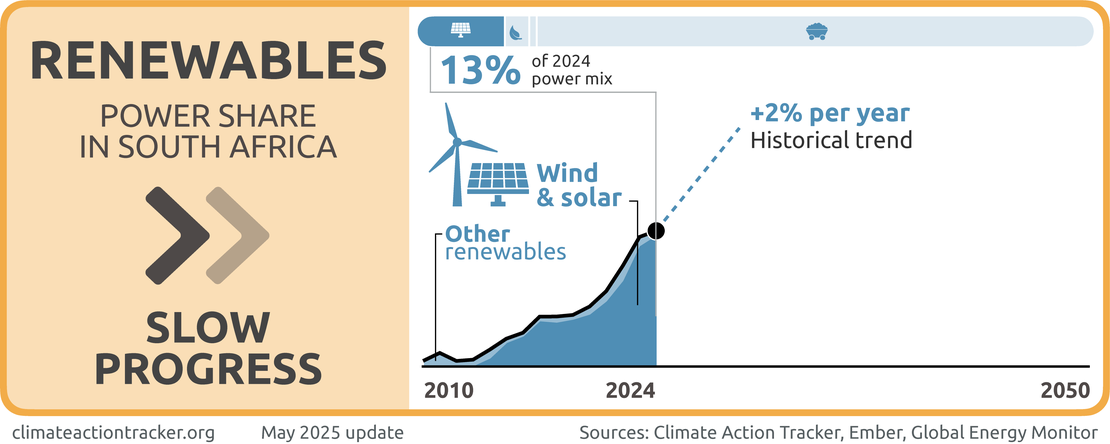

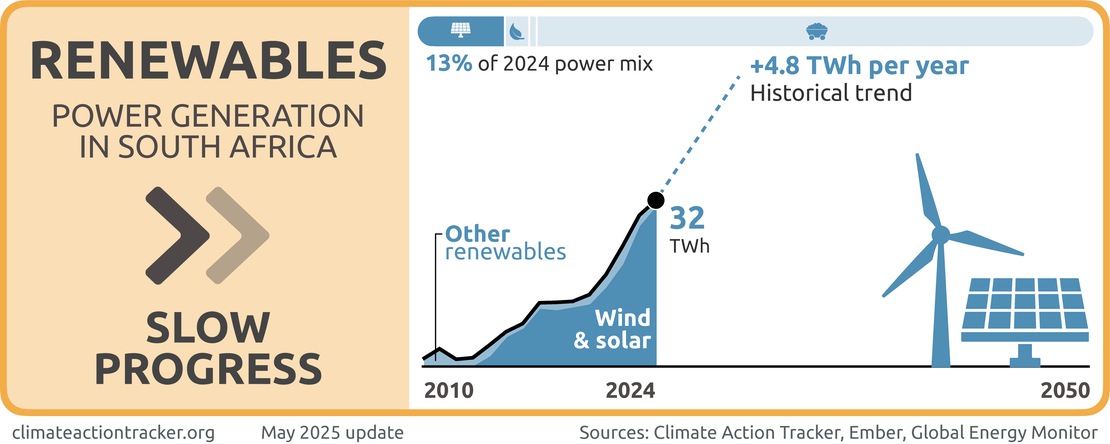

South Africa’s coal-dominated power sector is a major contributor to the nation’s emissions, accounting for over 40% of total GHG emissions in 2022 (South African Government, 2024b). Coal accounted for 82% of the country’s power mix, followed by renewables (13%), nuclear (3%), and oil (1%) (Ember, 2025).

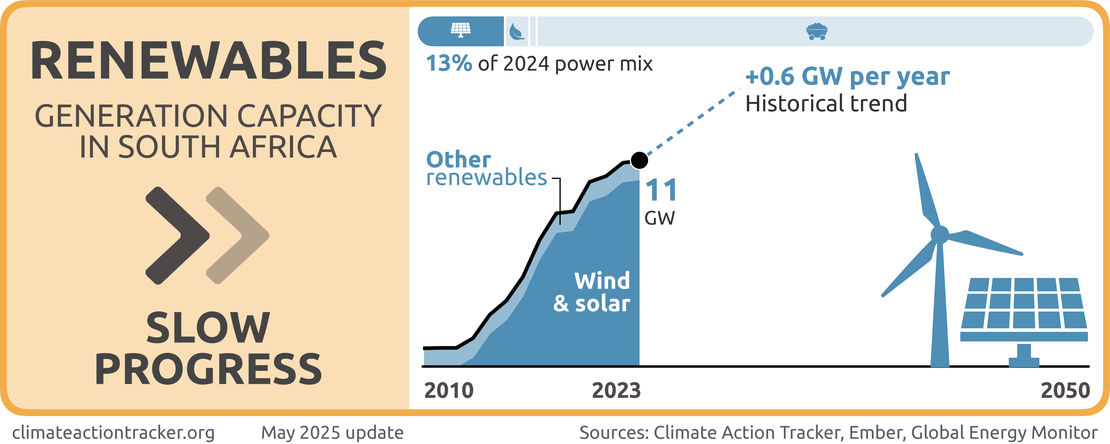

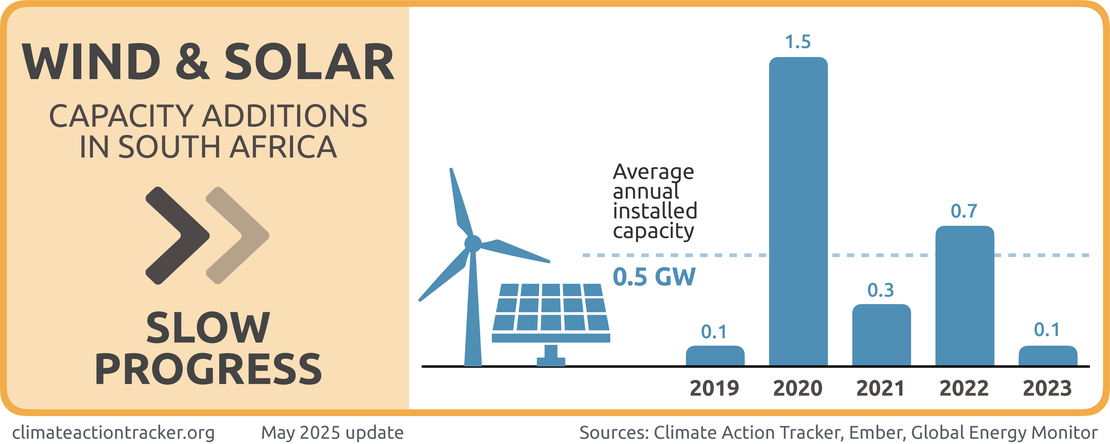

Total generating capacity in the country has been growing steadily and passed 62 GW in 2023, 8% larger than 2019’s installed capacity of just over 57 GW. Coal remains by far the largest source of power at almost 46 GW in 2023, at close to 74% of total generation capacity. Wind and solar capacity has been growing in South Africa in recent years, with utility-scale wind and solar capacity estimated to have grown by more than 30% since 2019, reaching 9.6 GW in 2023. Wind and solar have also increased as a share of total generation in South Africa in the past five years, from 4.5% in 2019 to 11.6% in 2023 (Ember, 2025).

This increase has occurred while overall electricity generation levels have been falling in South Africa. Total utility-scale electricity generated in 2023 was over 7% lower than the pre-Covid figure in 2019. This fall in demand largely reflects the energy crisis which the country has been enduring as opposed to efficiency gains.

South Africa’s ongoing energy crisis and policy response

South Africa’s power sector faces a severe undersupply of generation, exacerbated by its aging coal fleet, substantial under-investment in grid infrastructure and corruption. For over 15 years, Eskom, South Africa’s public utility, has continually resorted to power cuts lasting multiple hours to avoid damage to the grid (Ferragamo, 2023). Equipment breakdowns, maintenance, and repairs negatively affected the operation of multiple coal units in the country’s aging fleet throughout 2023 (Francke, 2023).

The government declared a national state of disaster in early 2023 as load-shedding intensified to make 2023 the worst year on record for power outages (BusinessTech, 2024). Persistent power cuts have significant consequences for people’s lives and livelihoods. A South African Reserve Bank study found the load-shedding in 2022 likely impacted GDP growth by -0.7 to -3.2% (Janse van Rensburg & Morema, 2023). In 2024, the situation improved, with Eskom reporting 300 consecutive days without load shedding. This hopefully signifies a lasting turning point for South Africa (Eskom, 2025).

The heavily indebted public utility Eskom has received a series of government funded bailouts but has so far been unable to fully stabilise the electricity system. In February 2023, the government provided Eskom with debt relief equivalent to over half of the company’s debt to enable investment and maintenance of the power system (Mukherjee, 2023a; National Treasury, 2023). A condition of the debt relief was a moratorium on new borrowing. Given Eskom’s position as the largest owner of generation assets in South Africa, this restriction has considerable implications for the country’s renewables build-out, with the role of private sector actors increasing in importance.

In seeking to address the ongoing crisis in the electricity system, South Africa is undertaking major structural reforms of its electricity market. These include the unbundling of Eskom’s transmission, distribution and generation functions into separate companies, increasing third-party generation, as well as exploring private sector involvement in the buildout and ownership of transmission infrastructure.

In 2024, the South African government passed the Electricity Regulation Amendment Act to establish an independent state-owned transmission network and operator, a role previously held by Eskom alongside its role as electricity generator (South African Government, 2024e). The new Transmission System Operator (TSO) must be established within five years in order to strengthen and develop electricity infrastructure and to establish a competitive market with multiple buyers and sellers, moving towards a decentralised system with greater private sector ownership of energy assets (Department of Mineral Resources and Energy, 2024d; Eskom, 2024a). Some regulatory decisions are already being contested, indicating the challenging nature of structural reforms and redistribution of influence in South Africa’s power sector (Times, 2024). But an effective evolution of South Africa’s electricity market structure is crucial to facilitate greater integration of renewables.

In addition to structural reforms, South Africa has introduced policies focusing on increasing levels of fossil and renewable power generation. Key policies and plans impacting the different energy sources are outlined below.

Coal

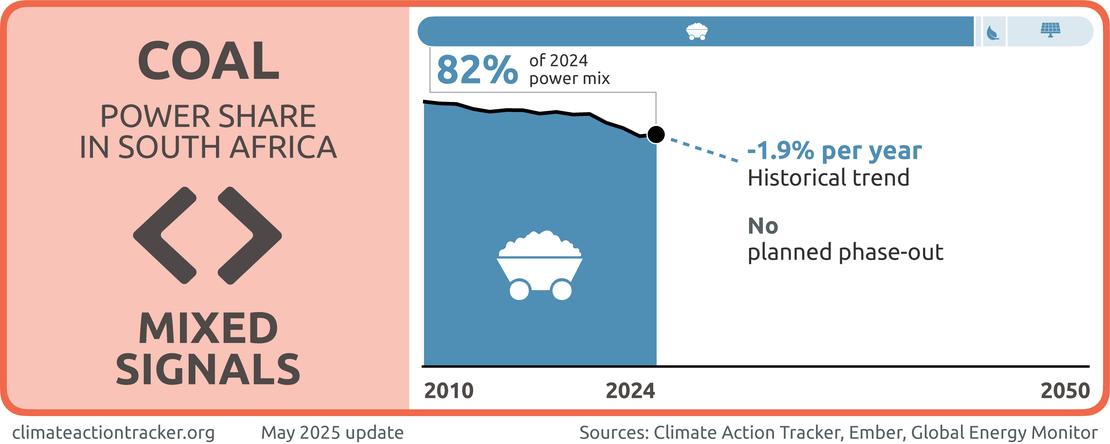

South Africa government is sending “Mixed signals” on coal. While the overall share of coal in the power sector has slowly declined in the last five years, the plant decommissioning roadmap appears to have been delayed, and new coal capacity was recently added to the grid.

The government outlines its plans for the power sector in iterative publications of the Integrated Resource Plan (IRP). The most recent draft 2023 IRP was published for comment in 2024 but the finalised report has yet to be made public, as of January 2025.

In contrast to the 2019 IRP, which called for decommissioning 12 GW of older coal capacity by 2030, the draft 2023 IRP strengthens focus on energy security and seeks to maintain existing coal capacity. In modelling the near-term outlook to 2030, the report recommends delaying coal plant decommissioning and continuing operation of plants beyond their scheduled lifetime if feasible. Actual decommissioning of coal plants does appear to have been delayed, indicating a change of priorities towards electricity stabilisation and energy security. According to the Global Energy Monitor, less than 1.2 GW have been retired as of October 2024 (Cunliffe, 2023; Global Energy Monitor, 2024).

In its pursuit of stabilising the electricity system, South Africa continues to add new coal plants to the grid, with Eskom connecting 800 MW of new coal capacity in June 2024 and nearing completion of a further 800 MW coal capacity in early 2025 (Eskom, 2024b; Green Building Africa, 2024). The nation is undoubtedly navigating a challenging period in its energy transition. Nonetheless, recent analysis suggests that these planned coal power plants will be significantly more expensive than their low-carbon alternatives (Ireland & Burton, 2018; Paton, 2018; PCC, 2023). In the context of extending reliance on coal, the South African energy minister signalled in July 2024 that the country is unlikely to meet its 2030 NDC targets (Reuters, 2024).

Despite the reversal in plans to decommission coal plants, it should be noted that the share of coal in generation in South Africa has been falling in recent years, from just over 89% in 2019 to less than 82% in 2024 (Ember, 2025). If a merit order dispatch system is created in the South African electricity market, as the government appears to have signalled in the Electricity Regulation Amendment Act, coal will become increasingly uncompetitive in scenarios with sufficient renewable generation and flexibility in the system. This will naturally occur if renewables are allowed to compete freely for dispatch, given the near-zero marginal operating cost of wind and solar generation. An ambitious application of the upcoming carbon budget system and enhanced carbon tax penalties will amplify these trends, highlighting the risk of stranded assets with further expansion of the coal fleet in South Africa.

Fossil gas

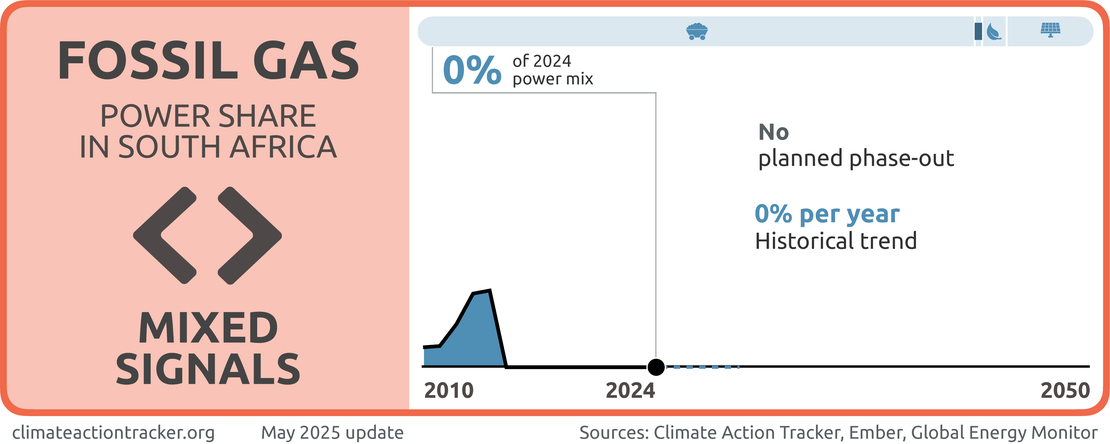

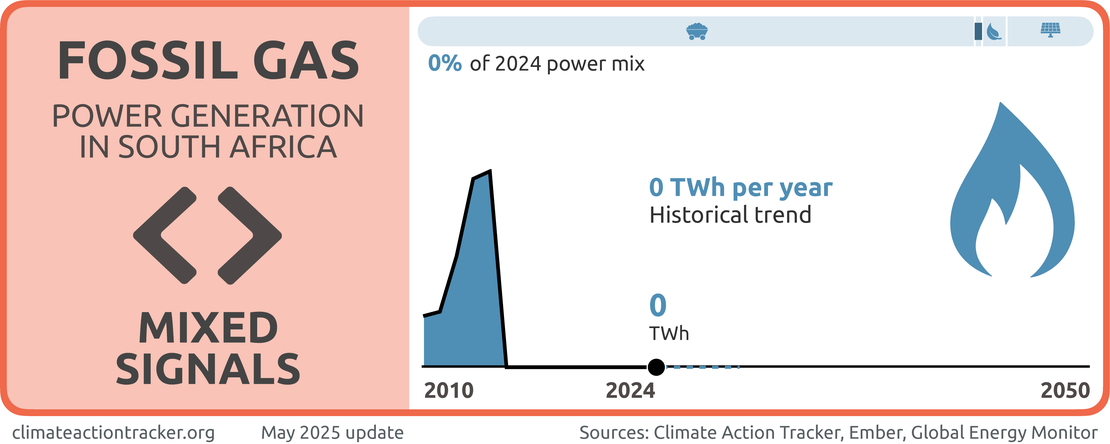

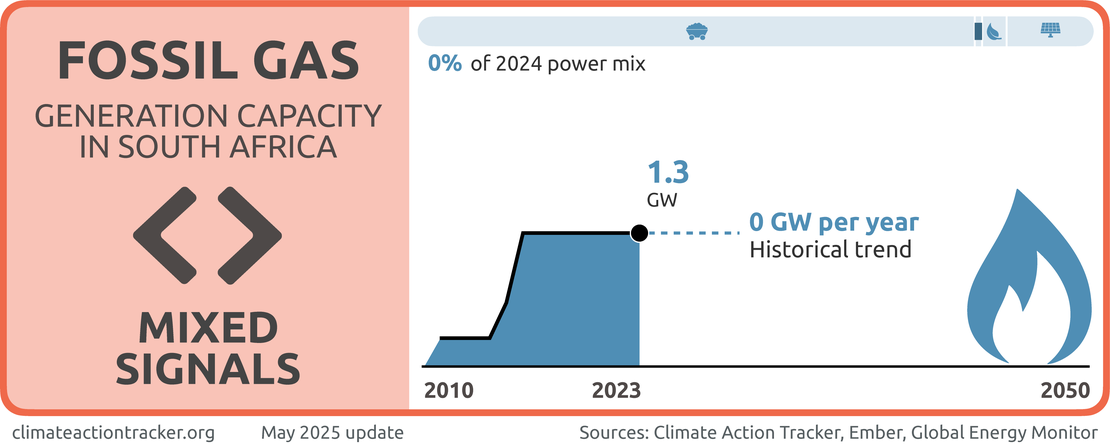

South Africa is sending “Mixed Signals” on fossil gas. Although there is currently no gas-fired power generation, the government intends to significantly expand its fossil gas capacity, as outlined in its draft 2023 IRP.

In a further reversal of policy intention from the 2019 IRP, the modelling results presented in the draft 2023 IRP suggest fossil gas capacity would reach close to 11 GW in 2030 instead of the previously planned 7 GW. The draft 2023 IRP also discusses potential means of increasing fossil gas supply for South Africa, signalling a lack of ambition to transition from coal directly to renewables with a phase-out of all fossil fuels.

South Africa has begun implementing stated plans to increase fossil gas capacity, although progress is slow. In December 2023, the government issued a request for proposal for 2 GW of fossil gas power plant capacity. The bid window has since been extended to March 2025 following issues with the initial process, meaning additional gas capacity is yet to enter construction stage, as of early 2025 (Department of Mineral Resources and Energy, 2024a).

Renewables

South Africa is making “Slow Progress” on deploying renewables. Despite commendable progress in recent years in challenging circumstances, the country’s grid remains dominated by fossil fuels. The approved 2019 Integrated Resource Plan targeted 27.6 GW of renewables to be installed by 2030, excluding large hydro. At just under 10 GW of installed renewable capacity as of 2023, South Africa’s renewable expansion plans are off-track (Cunliffe, 2023). Furthermore, the draft 2023 IRP lowered the expected installed capacity of wind and solar by 2030. Nonetheless, wind and solar capacity and generation has been ramping up in South Africa in recent years, rising from 4.5% of total generation in 2019 to 11.6% in 2023 (Ember, 2025). South Africa will need international support to ensure that current ambition levels are retained and increased further to maximise the country’s potential for renewable electricity generation.

As such, it is imperative that current ambition levels are retained and increased further to maximise the potential for renewable electricity generation in South Africa.

Key policies supporting this trend are the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme (REIPPPP) and the removal of licencing requirements for distributed generation projects up to 100 MW in size. The government has also introduced generous tax rebates to incentivise installation of rooftop solar by commercial and residential customers.

The REIPPPP is presently South Africa’s core method of procuring new renewable capacity. It is a competitive tendering process that invites bids from private operators to develop grid-scale renewable energy capacity. Winning bids are awarded a power purchase agreement, with Eskom typically providing the offtake agreement. Launched in 2011, the REIPPPP successfully galvanised over USD 16bn in successive bid windows in its first 5 years (NDC Partnership, 2016). Most recently, bid window 7 closed in 2024 with the goal of procuring an additional 5 GW of wind and solar capacity. In December 2024 preferred bids of close to 2.5 GW in new wind and solar capacity were announced and additional winning bids may also be procured (Department of Electricity and Energy, 2024; South African Government, 2024a).

The REIPPPP has been very successful in generating interest in renewable energy project development, with all bidding rounds significantly over-subscribed. However, considerable delays in bid rounds and in connecting the procured renewable projects to the grid have arisen. Many South African projects have stalled due to the elevated interest rates and supply chain challenges of recent years (Mukherjee, 2023b).

The second important policy support for renewable expansion is the removal of licencing requirements for distributed projects. In 2021, the government increased the threshold for licencing requirements from 1 MW to 100 MW projects, followed by complete removal of thresholds in December 2022. According to the draft 2023 IRP, these changes have resulted in the registration of an additional 6 GW of distributed generation, but it is not clear what share of this new capacity is renewable (Department of Mineral Resources and Energy, 2024b, 2024c).

Finally, in 2023, the government announced a generous tax rebate scheme to incentivise renewables installation by South African companies. Until 2025, the scheme enables businesses to claim 125% of the cost of installation of renewable generation projects against their tax bill in the year of installation. Another tax incentive has been introduced for households to recover 25% of the costs of installation (South African Government, 2023b).

Given South Africa’s ongoing challenges with transmission infrastructure, off-grid distributed renewables are a promising avenue to stabilise supply and decarbonise electricity in the country, although it is a solution available to higher income households and businesses only.

Overall, these policy trends present a positive outlook for renewables expansion in South Africa in the near term.

Industry

South Africa is host to significant heavy industry with large scale steel and ferroalloy production, along with chemical and cement manufacturing and other industrial activities. These activities account for a substantial share of national emissions, according to South Africa’s most recent UNFCCC National Inventory Report. The government estimates that non-energy emissions in the IPPU sector fell by close to 7% between 2000 and 2022, largely driven by falling demand for industrial goods rather than by policy (South African Government, 2024b, p. 40).

The carbon tax is one of the few mechanisms to directly target industrial emissions, but it has permitted generous tax-free allowances and other deductions to date and has thus not served as a strong incentive to decarbonise industrial operations. It remains to be seen how the tax may be strengthened with the introduction of sectoral carbon budgets as part of the Climate Change Act. The current proposals from the South African Treasury suggest the continuation of generous offsets for the industry sector (National Treasury, 2024).

Policy and planning documents for the South African industry sector generally address sustainable industrial economic development but feature little mention of mitigation targets for the industry sector, nor concrete measures for implementation. The post-2015 draft National Energy Efficiency Strategy proposed industrial sector targets for energy efficiency by 2030 (Department of Energy, 2016). However, as of 2025, there is no follow-up publication detailing implementation.

Further implemented policy measures which target improved energy efficiency in the South African industry include the National Cleaner Production Centre South Africa, a network and information provision programme that promotes energy efficiency measures; its associated Industrial Energy Efficiency Project (IEEP), implemented between 2011–2021, that promoted energy management systems and international best practice energy management standards; the 12L tax incentive which allows businesses to write off verified energy savings from efficiency projects against tax due; and the Green Fund South Africa that financially supports green technology research and implementation. However, these measures may only induce small emissions reduction impacts.

Beyond efforts to decarbonise and improve efficiency, South Africa is also aiming to develop value chains for renewable energy and storage technologies through the South African Renewable Energy Masterplan (SAREM), released for public comment in July 2023 (The dtic, 2023). The plan particularly aims to take advantage of increasing domestic and international demand for these technologies to drive industrial development and create jobs as part of the just transition.

There are limited signs of policy-driven emission reductions in the near future for emissions-intensive subsectors such as steel production and mining, though there has been some interest in hydrogen. The Hydrogen Society Roadmap (2021) and draft Green Hydrogen Commercialisation Strategy (2020) highlight the potential role of hydrogen, and steps to develop green hydrogen for use in steel production, industrial mining, mineral beneficiation, manufacturing, logistics, and other sectors (DSI, 2021; The dtic, 2022). The South African Steel and Metal Fabrication Master Plan 1.0 (2021) mentions hydrogen, along other measures, in consideration of greening the industry (The dtic, 2021). For hydrogen to decarbonise the industry sector, it must be produced using renewable energy.

Analysis by the Climate Action Tracker indicates that the steel industry’s emissions intensity would need to be reduced by about 30% in 2030 and by about 90%-100% by 2050 to be compatible with the Paris Agreement.

Transport

South Africa’s 2024 National Inventory Report estimates that emissions from transport represented around 11% of total GHG emissions in 2022, excluding LULUCF. The overwhelming majority of transport emissions come from road transport (South African Government, 2024b). The South African government estimates that transport emissions have been steadily increasing, with an estimated increase of 27% in transport emissions since 2000.

In 2018 the Department of Transport published the first Green Transport Strategy (GTS) 2018–2050 (Department of Transport South Africa, 2018), proposing a list of measures encompassing public transit development, electric and alternative fuelled vehicles that should be implemented to transition the sector to a low carbon future. The Biennial Transparency Report, published in December 2024, highlights three measures as the most impactful transport focused policies. These are the Bus Rapid Transport System project, which aims to develop bus networks in South Africa’s major cities; the Transnet Road to Rail Programme, which aims to shift freight transport from trucks to more carbon efficient rail; and projects within the Just Energy Transition partnership which focus on Electric Vehicles (EVs), primarily the development of EV manufacturing. In addition to these policies, South Africa has also mandated the blending of biofuels into petrol and diesel supplies, although currently at very low levels (Department of Mineral Resources and Energy, 2020b; IEA, 2024).

Bus Rapid Transit Systems (BRT) have initiated the main switch in modal share of passenger transport in urban areas. Initiatives to expand BRT systems are currently taking place in eight cities and municipalities including Cape Town and Johannesburg. However, BRT still faces challenges such as competition with minibus taxis and overreliance on foreign service plans less suitable for South African cities (Hook & Weinstock, 2021).

South Africa has a large car manufacturing sector, and the government is targeting increased domestic EV production (Department of Trade Industry and Competition, 2021). The automotive industry is one of the country’s largest manufacturing and highest value-added sectors, contributing to over 4% of GDP in 2021 (NAAMSA, 2023). In 2013, the government adopted South Africa’s Electric Vehicle Industry Roadmap to introduce electric passenger vehicles (EVs) (South African Government, 2013).

Three years after the adoption of the roadmap, the first EV was manufactured in South Africa with the production of plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) at Mercedes-Benz’s East London plant (Venter, 2023). Since then, Toyota has also begun manufacturing PHEVs and Ford also announced it will manufacture PHEVs in South Africa (Agbetiloye, 2023; Venter, 2021). While this shows some progress, the industry is still dominated by fossil fuel-vehicles, creating an existential challenge for the auto industry as South Africa’s main export destinations, such as the UK and EU, shift towards EVs (NAAMSA, 2023). In 2025, the government has taken further action to incentivise domestic EV production, introducing a tax deduction worth 150% of the costs of new or improved buildings and machinery for EV manufacture. The tax incentive will apply between 2026 and 2036 (Green Building Africa, 2025; South African Government, 2024d).

On the demand-side, the total number of EVs vehicles sold in South Africa remains marginal. The number of battery EVs sold has been rising in South Africa, but the share in total sales remains low representing just 0.24% of new vehicle sales in 2024 (Kuhudzai, 2025).

Analysis by the Climate Action Tracker shows that the electric vehicle share in annual vehicle sales in South Africa would need to increase to 50–95% by 2030 and 90–100% by 2040 to be compatible with the Paris Agreement.

Buildings

South Africa’s commercial and residential buildings have undergone a major fuel switching process over the past two decades. In both building categories, onsite fuel consumption has fallen dramatically while the use and proportional share of electricity in building energy consumption has been steadily rising (South African Government, 2024b, pp. 80–82). Nonetheless, direct and indirect building emissions per capita in South Africa have been increasing in recent years (Climate Transparency, 2022).

The move away from biomass and coal use for cooking and heating towards the use of more modern appliances that require electricity, which is largely generated by fossil fuels, might significantly increase indirect emissions without a rapid shift to renewables in the power sector. However, the health and welfare benefits resulting from these fuel switching developments are likely to be significant. The increasing electrification of buildings provides a clear pathway to decarbonising the sector via decarbonisation of electricity generation.

Analysis by the Climate Action Tracker suggests that the buildings emissions intensity would need to decline by 50% for residential buildings by 2030 below 2015 values, 90% by 2040, and 100% by 2050 to be compatible with the Paris Agreement.

South Africa has implemented several policies targeting improved energy efficiency and renewable energy use in buildings. In addition to the tax incentives for solar panel installations introduced in 2023 and 2024, active policies include the 12L Tax Incentive for businesses implementing energy efficiency measures, including building measures; public funding for upgrading of municipal buildings; and minimum energy performance standards and labelling requirements for appliances.

In the National Development Plan 2030, the government has also stated an intention to develop zero-emission building standards by 2030 (South African Government, 2012). This would represent a strengthening of the existing standards and codes that South Africa has applied to energy efficiency and usage in new buildings and for major refurbishments of old buildings (Sustainable Energy Africa, 2017).

Relatedly, the government released a regulation for mandatory energy performance certificates in 2020 (Department of Mineral Resources and Energy, 2020a). The regulation applies to four different classes of larger-scale buildings and building owners were required to be compliant by the end of 2022 (Smith, 2021). The compliance date was subsequently extended to the end of 2025 (Department of Mineral Resources and Energy, 2025).

The draft Post-2015 National Energy Efficiency Strategy, which has not been finalised as of 2025, targets reductions of the final energy consumption by 33% in the residential sector and 37% in the public and commercial sector by 2030, compared to a 2015 baseline (Department of Energy, 2016). Information on implementation and tracking of the targets from the Energy Efficiency Strategy, however, does not appear to be available. The upcoming sectoral budgets in the Climate Change Act should result in specific emissions reduction targets for the buildings sector, if implemented rigorously.

Agriculture

In 2022, agriculture accounted for just over 10% of South Africa’s emissions, with the majority coming from livestock. Emissions from agriculture have remained relatively constant since 2000 (South African Government, 2024b).

A limited number of policies in South Africa’s agricultural and forestry sector target climate change mitigation. The 2024 Biennial Transparency Report lists the Comprehensive Agricultural Support Programme as the core policy targeting agriculture. This programme provides technical advice and financial support to farmers and includes increasing sustainable farming practices among its objectives. However, further details of its links to decarbonisation of the sector are not readily available.

The National Climate Change Response Strategy, a climate strategy published in 2011, names climate smart agriculture (CSA) as a practice “that lowers agricultural emissions, is more resilient to climate changes, and boosts agricultural production” (Government of South Africa, 2011). A number of CSA activities are already in place in South Africa (Nciizah & Wakindiki, 2015), but their expected or actual mitigation impacts are not reported.

In 2018, the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, now the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment published two draft agricultural policies for public comment: the draft Conservation Agriculture Policy and the draft Climate Smart Agriculture Strategic Framework (DAFF, 2018a, 2018b).In 2020, a set of guidelines for implementing the practice were published by the department but no legally binding requirements or other policy incentives appear to have been introduced (South African Government, 2020a).

Forestry

Forestry and other land use (FOLU) in South Africa is a net sink of emissions, meaning more carbon is sequestered than emitted. This net sink has overall been increasing since 2008, reaching over 25 MtCO2e in 2020 (DFFE, 2023). According to the 2024 Biennial Transparency Report, the LULUCF sector overall provided a sink of more than 40 MtCO2e in 2022.

A number of mitigation related policy measures in South Africa’s forestry and other land use sector are in operation. The 1st Biennial Transparency Report lists ongoing work programmes on afforestation, forest and woodland restoration and rehabilitation, grassland rehabilitation and thicket restoration. It notes that the National Forests Amendment Act of 2022 aims to promote sustainability in the sector (South African Government, 2022a).

Given the importance of the timber industry, the area of woody crops increased by over 50% since the early 1990s and stabilised over the 2010s (FAOSTAT, 2023). South Africa’s latest national inventory report indicates overall forest land has increased over the same period, however, other sources indicate the tree cover has continuously decreased (DFFE, 2023; FAOSTAT, 2023). It is unclear whether methodological differences or varying definitions are the reason for this apparent mismatch.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter