Country summary

Overview

It remains doubtful whether South Korean President Moon Jae-In’s plan to reduce the power sector’s share of coal and nuclear power - and increase renewables - would lead to the substantive greenhouse gas emissions reductions needed to meet the country’s “highly insufficient” 2030 climate pledge (NDC), let alone to reduce emissions in line with the Paris Agreement’s long-term goal.

The third Energy Master Plan up to 2040 adopted in June 2019, together with the 2017 power sector plan for the period up to 2030, aims to increase the renewable electricity share to 20% by 2030 and 30–35% by 2040 - up from 3% in 2017. The government has yet to commit to a complete phase-out of its coal-fired power plants. Climate Action Tracker projects that South Korea will remain short of reaching its targeted 20% renewable energy share by 2030.

The new plan suggests the government is still considering giving permits to seven coal fired power plants, which is disappointing given it had, in May 2017, announced it was reconsidering plans for all coal fired power generation. Coal would still account for more than a third of generated electricity in 2030 – at odds with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5˚C temperature goal that requires an OECD phase-out of coal by 2030, and by 2050 globally.

The increased target for renewables was a positive sign that the government is willing to take stronger actions to tackle climate change. However, if fully implemented, the plan would only stabilise, not decrease emissions (see “Planned policy projection” in the graph), as South Korea's power generation mix will, under this plan, continue to remain heavily dependent on fossil fuel-fired power. However, based on recent literature, the CAT projects that the government will fall short of this 2030 renewables target.

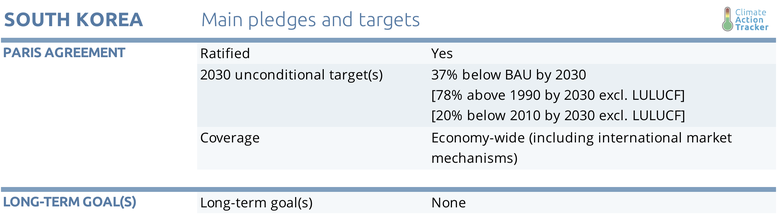

Overall, South Korea still needs to substantially strengthen its Paris Agreement target, which we currently rate “Highly insufficient”. What is worse, current and planned policy projections are far from meeting its NDC target and would be rated “critically insufficient”. The government still needs to implement more stringent policies for this weak target, let alone the level of action needed to be considered “1.5˚C-compatible”.

Air pollution from coal-fired power plants has been a serious issue in South Korea, which has been a key driver for the recent announcement of early retirements of six old plants. Climate change mitigation - and the considerable air pollution benefits it would deliver - could gain significant attention in the next general election in April 2020.

Currently implemented policies are estimated to lead to an emissions level of 727–786 MtCO2e/year in 2030 (150–155% above 1990 levels), excluding emissions from land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF). To reach its 2030 NDC target, South Korea will have to significantly strengthen its climate policies.

For the power sector, the impact of the Eighth Electricity Plan is not quantified in CAT’s analysis of South Korea’s current policy projections, due to the lack of laws or measures to implement them. The CAT estimates that if fully implemented (and taking into account the expected lower level of electricity demand highlighted above), these announcements would lead to about 20% reduction in electricity-related emissions below the upper bound projections of the current policies scenario in 2030 (refer to “Planned policy projection” on the graph above) and result in similar emission levels as the lower bound projections of the current policies scenario.

The Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS), which replaced a previous feed-in tariff scheme and has been in place since 2012, is the main policy instrument to promote renewable energy. The RPS scheme requires major electric utilities to increase their renewable and “new energy” share in the electricity mix to 10% by 2023 (Korea New and Renewable Energy Center, 2019). Our current policies scenario projections on renewable electricity is modest partly due to this unambitious RPS.

One of the main cross-sectoral policy instruments implemented to date is the Korea Emissions Trading Scheme launched in 2015 (ICAP, 2019b). The ETS cap for Phase II (2018–2020) was announced in July 2018 and is set to increase from 1,686 CO2e in Phase I (2015–2017) to 1,796 CO2e in Phase II.

In the transport sector, the number of annual electric vehicles (EVs) sales doubled from 2017 to 2018 to 33,000, accounting for over 2% of total new car sales in 2018 (IEA, 2019a). The South Korean Government is pushing the uptake of EVs through subsidies and tax rebates (IEA, 2019a), with the goal of having 430,000 EVs on the road by 2022. The government is also investing in a programme to improve charging infrastructure.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter