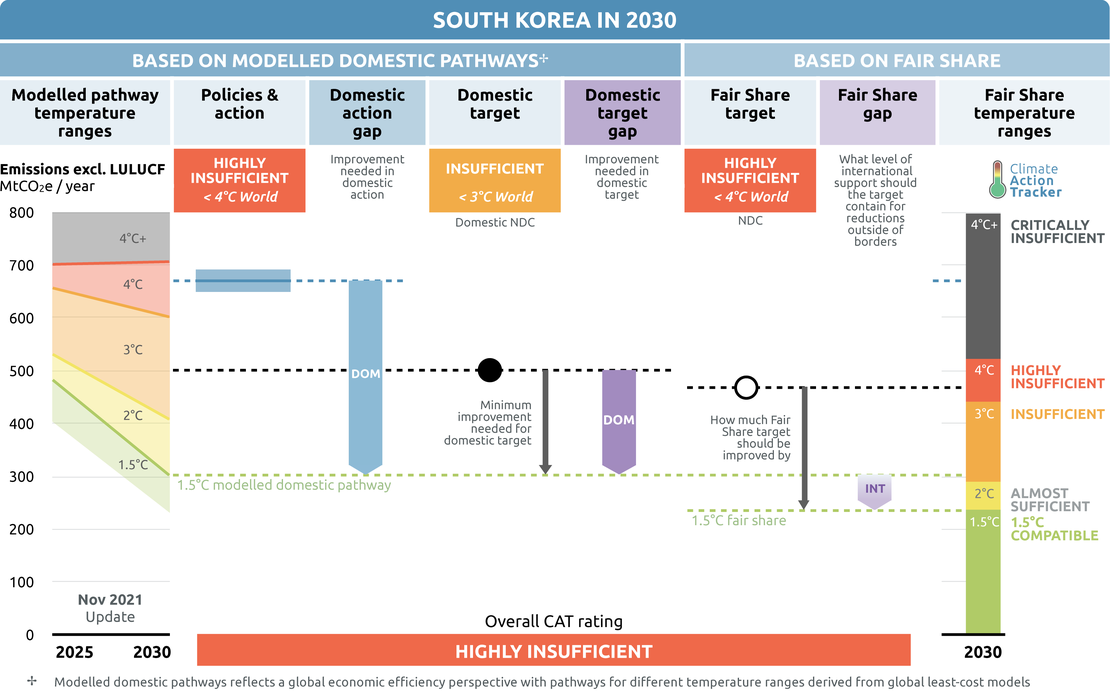

Policies & action

We rate South Korea’s policies and action as “Highly insufficient”. The “Highly insufficient” rating indicates that South Korea’s policies and action in 2030 are not at all consistent with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C temperature limit. If all countries were to follow South Korea’s approach, warming could reach over 3°C and up to 4°C.

South Korea’s climate neutrality target is enshrined in law through the Framework Act on Carbon Neutrality and Green Growth (Carbon Neutrality Act), which was passed in August 2020. The Act introduces a climate impact assessment, which is aimed to assess the climate impacts of major national plans and development projects. Emissions reductions targets will now be integrated into national budget planning through the climate-responsive budgeting program. The Act also sets up a climate response fund, which will be used to support the structural transformation of carbon-intense industries.

The Green New Deal was announced in 2020, and commits around USD 31bn to green remodelling, green energy, and eco-friendly vehicles (Ministry of Economy and Finance, 2020).

By 2025 the Green New Deal targets 42.7 GW of renewable power capacity, 1.13 million electric cars, 200,000 hydrogen cars, and the scrapping of 2.2 million old diesel cars. The final deal did not introduce the carbon tax as promised earlier in the year, however, this is mentioned as a planned policy in South Korea’s 2050 carbon neutrality scenarios, published in October 2021 (Republic of Korea, 2021b).

Another promise was to stop coal financing, and this commitment was confirmed in April 2021 at the U.S. Leaders’ Summit on Climate, where South Korea announced it will immediately stop financing coal projects abroad (Wang, Liu and Wang, 2021). Yet, just one month later, exceptions were announced for retrofitting, CCS, and approved projects (SFOC, 2021). Despite this backpedalling, major Korean financial groups like KB, Shinhan, Hana, and Woori, have all announced plans to make their investment portfolios carbon neutral by 2050 (Jee-Hee, 2021).

The two framework policies for the energy supply sector are the 3rd Energy Master Plan adopted in June 2019 for the period up to 2040 (MOTIE, 2019a) and the Ninth 15-year Basic Plan for Electricity Supply and Demand (Ninth Electricity Plan) adopted in December 2020 for the period up to 2034 (MOTIE, 2020). The 3rd Energy Master Plan aims to increase the renewable electricity share to 20% by 2030, and to 30–35% by 2040 - up from around 6% in 2020 (IEA, 2021b), mainly by increasing the total renewable power capacity up to 129 GW (MOTIE, 2019a). The Ninth Electricity Plan sets a similar renewables target of 20.8% in 2030 and envisages a significantly lower electricity demand growth. The plan includes the retirement of 24 coal plants (but not before their economic lifetime (Lee, 2021)), and considerable roles for LNG and nuclear, which are targeted to account for 23% and 25%, respectively.

One of the main cross-sectoral policy instruments implemented to date is the Korea Emissions Trading Scheme launched in 2015 (ICAP, 2019). In comparison with its previous phase, Phase III (2021-2025) targets a 4% reduction in emissions, expands coverage of national GHG emissions from 68% to 73.5%, increases auction shares, and tightens benchmarks for coal-fired power generation.

The Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS), replaced the previous 2012 Feed-in Tariff scheme, and is the main policy instrument to promote renewable energy in South Korea. The RPS scheme requires major electric utilities to increase their renewable and “new energy” share in the electricity mix to 10% by 2023 (Korea New and Renewable Energy Center, 2019). The revised Renewable Energy Act, passed in March 2021, raised the threshold to 25% by 2034.

Currently implemented policies are estimated to lead to an emissions level of 649-691 MtCO2e/year in 2030 (‑3% to 3% relative to 2020 levels, or 106% to 120% above 1990 levels) depending on the eventual impact of the COVID-19 crisis, excluding emissions from land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF).South Korea announced that it will join the Global Methane Pledge and reduce methane emissions by 30% compared to 2018 (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of South Korea, 2021). This means a reduction of about 10 MtCO2e in 2030 below the CAT projections for policies and action.

Policy overview

Between 1990 and 2020, South Korea's emissions more than doubled. Emissions steeply increased in the early 1990s, with growth then continuing at a slower pace. The CAT projections for current policies show emissions decreasing from 2020, leading to an emissions level of 649-691 MtCO2e/year in 2030. South Korea currently commits, in its NDC, to achieve 540 MtCO2e/year excluding LULUCF (81% above 1990 emission levels). To reach this target, South Korea needs to significantly strengthen its climate policies, even more so if the country is to achieve its new 2030 target or carbon neutrality by 2050.

One of the main cross-sectoral policy instruments implemented to date is the Korea Emissions Trading Scheme launched in 2015 (ICAP, 2019). Phase III (2021-2025) of the ETS was announced in September 2020 and increases the scope from 68% to 73.5% of national GHG emissions, covering 685 companies in 69 subsectors, including steel, cement, petrochemicals, refinery, power, buildings, waste, and aviation (Ministry of Environment, 2020). The ETS system includes both direct and indirect emissions (emissions from electricity use). The allowable share of offsets for an entity’s compliance obligations decreases from 10% to 5%, while the share of auctioning for 41 of the 69 covered sub-sectors will increase from 3% to 10%, in comparison to the previous phase. The remaining sub-sectors receive 100% free allocation, determined by an assessment of carbon leakage. The increased shared of auctioning, however, remains low compared to the EU ETS, which in Phase IV auctions 57% of allowances (International Carbon Action Partnership (ICAP), 2021).

The Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) replaced the Feed-in Tariff scheme in 2012 and is the main policy instrument to promote renewable energy. The RPS scheme requires major electric utilities to increase their renewable and “new energy” share in the electricity mix to 10% by 2023 (Korea New and Renewable Energy Center, 2019). The revised Renewable Energy Act, passed in March 2021, raised the threshold to 25% by 2034.

The Ninth Electricity plan sets clear electricity mix targets, which confirmed the Moon administration’s intention to shift electricity generation away from coal (MOTIE, 2020). The target scenario in the Ninth Plan envisages a reduction in the share of coal from 40.4% in 2019 to 29.9% in 2030 and an increase in renewables, from 6.5% in 2019 to 20.8% in 2030, while significant roles are still envisaged for nuclear (25%) and LNG (23.3%). We estimate that this shift in the power mix, together with the decreased electricity demand detailed in the Ninth Plan, would lead to a 5% reduction in total emissions compared to the Eighth Plan.

In the revised 2030 GHG Roadmap, published in 2019, South Korea provides details on sector-specific reduction targets as well as policy options. For the building sector, the plan mentions strengthening permit standards for new buildings, promoting green renovation, identifying new circular business models, and expanding renewable energy supply. For the industry sector, the plan focuses on energy efficiency and industrial process improvement measures but also on the promotion of eco-friendly raw materials and fuel (Ministry of Environment, 2018).

The Hydrogen Roadmap, published the same year, sets targets for hydrogen in the transportation and energy sectors: 2.9 million hydrogen vehicles by 2040 and 15 GW of power generating capacity from fuel cells (MOTIE, 2019b). South Korea’s current hydrogen demand of 13,000 t/year in 2019 is produced from petrochemical industry by-products. Under the Hydrogen Roadmap, the demand will increase to 5.36 million t/year by 2040; the additional demand in the short-term will be met by LNG and therefore will not lead to significant emissions reductions. South Korea is, however, investigating options for producing green hydrogen in the long-term.

In December 2020, the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries announced the First National Plan for the Development and Popularisation of Green Ships (2021-2030), which aims to explore advanced emissions-free technologies and sets targets to reduce shipping emissions by 70% by 2030 and convert 15% Korean ships to “green ships” (Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, 2021).

Energy supply

In 2020, electricity and heat production accounted for 53% of national CO2 emissions from fuel combustion (IEA, 2021a). South Korea’s power generation increased fivefold over the period 1990–2020 and is dominated by coal-fired (39% in 2020) and nuclear generation (27% in 2020) (IEA, 2021b). In 2020, the share of coal-fired power generation decreased from 43% to 39%, compensated by increases from LNG (+0.7%), nuclear (+2.2%), and solar (+1.2%). This shift resulted in record-low carbon intensity of South Korea’s electricity sector. However, the share of fossil fuels remains very large at 67% in 2020 and while the share of renewables in the sector has doubled in the last five years, it remains small at around 6%, considerably lower than the EU, Japan, and the US (see Figure below).

Motivated by air pollution, concerns over safety of nuclear power plants and climate change, President Moon Jae-In intends to reverse the policy direction of his predecessors by reducing reliance on nuclear and coal-fired power and increasing the share of renewable electricity in the long-term. The Green New Deal, announced in 2020, commits around 9.5 billion USD to green energy projects and targets 42.7 GW of renewable power capacity by 2025 (Ministry of Economy and Finance, 2020).

The two framework policies for the energy supply sector are the 3rd Energy Master Plan adopted in June 2019 for the period up to 2040 (MOTIE, 2019a) and the Ninth 15-year Basic Plan for Electricity Supply and Demand (Ninth Electricity Plan) adopted in December 2020 for the period up to 2034 (MOTIE, 2020). The 3rd Energy Master Plan was developed in concert with the previous Eighth Electricity Plan (MOTIE, 2017).

The 3rd Energy Master Plan aims to increase the renewable electricity share to 20% by 2030, and 30–35% by 2040 - up from 3% in 2017 (IEA, 2019), mainly by increasing the total renewable power capacity up to 129 GW. This plan, however, neither sets targets for reducing the share of coal and nuclear power, nor a timeline for the phase-out of coal-fired power plants.

The Ninth Electricity plan sets clear electricity mix targets, which confirmed the Moon administration’s intention to shift electricity generation away from coal (MOTIE, 2020). The base scenario presented shows the retirement of 24 coal power plants by 2030, leading to a reduction in coal-fired power generation from 40.4% in 2019 to 34.2% in 2030, while the target scenario presented includes further retirement of coal capacity, leading to a 29.9% share in 2030.

The 2030 share of nuclear and renewables in both scenarios remain at 25.0% and 20.8%, respectively – the reduction of coal share between the base and target scenarios is compensated entirely by LNG, which ranges between 19.0% and 23.3% in 2030. Compared with the shares presented in the Eighth Electricity Plan, the share of coal in the power mix is slightly reduced, but this is compensated by an increasing share of nuclear and LNG, not renewables. We estimate that if fully implemented (and accounting for the reduced electricity demand forecast highlighted above), the Ninth Plan would lead to a 5% reduction in total emissions compared to its predecessor.

While this plan is a slight improvement on the previous revision, fossil fuels will still account for over 53% of the power mix in 2030. The long-term reliance on fossil fuels is a burden for South Korea considering it relies almost entirely on imports to meet fossil fuel consumption, and is among the world’s top five importers of LNG, coal, and petroleum liquids (US EIA (U.S. Energy Information Administration), 2020).

In terms of research and development of advanced technologies, the roadmap for hydrogen economy published in January 2019 (MOTIE, 2019b) sets a goal of power generating capacity from fuel cells from 308 MW in 2018 to 15 GW by 2040. South Korea’s current hydrogen demand of 13,000 t/year in 2019 is produced from petrochemical industry by-products. Under the Hydrogen Roadmap, the demand will increase to 5.36 million t/year by 2040, and the additional demand in the short-term will be met by LNG, so will not lead to significant emissions reductions. South Korea is, however, investigating options for producing green hydrogen in the long-term.

The Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) replaced the Feed-in Tariff scheme in 2012 and is the main policy instrument to promote renewable energy. The RPS scheme requires major electric utilities to increase their renewable and “new energy” share in the electricity mix to 10% by 2023 (Korea New and Renewable Energy Center, 2019). The revised Renewable Energy Act, passed in March 2021, raised the threshold to 25% by 2034. This law is effective from October 2021 and will support South Korea in achieving its renewable energy targets.

South Korea’s power sector policies and plans are far from being compatible with the Paris Agreement 1.5 °C temperature limit, under which coal-fired power must be phased-out before 2030 and the role of LNG also needs to decrease. The Ninth plan shows that coal will not be phased out until 2054, with 27 GW coal capacity still online in 2034. Climate Analytics estimates that a Paris-compatible decommissioning schedule would require South Korea to retire 4.2 GW of coal capacity each year (Ganti et al., 2021). Under this scenario, units currently under construction would only operate for four years. These scenarios could halve the number of premature deaths linked to air pollution from South Korean coal plants within the next five years and prevent 18,000 premature deaths in the long-term, when compared to the current 2054 phase-out plan (Ganti et al., 2021).

In a similar analysis, Climate Analytics estimate that an accelerated, Paris-compatible, coal-to-renewables transition could lead to almost a threefold increase in jobs when compared to the 2054 phase-out plan (Zimmer et al., 2021). In the scenario presented, job losses related to the coal phase-out would be outweighed by newly created jobs in the construction, installation, operation and maintenance of renewable energy and energy storage infrastructure, which amount to 63,000 additional jobs by 2025 and up to 92,000 in 2030.

South Korea could increase its renewable energy target from 20.8% in 2030 to more than 50% in 2030, particularly given a number of studies demonstrate that South Korea could achieve high shares of renewable energy, including reaching close to 100% by 2050 (Hong et al., 2019; Climate Analytics, 2020).

Industry

In 2019, the industry sector accounted for 11% of national CO2 emissions from fuel combustion (IEA, 2021a). The main policy regulating industrial emissions is the ETS, which in Phase III (2021-2025) covers 73.5% of national GHG emissions and 685 companies in 69 subsectors, including main industries like steel, cement, and petrochemicals. Companies subject to the ETS are eligible for financial support from the government, which can be used to install energy-efficient equipment and processes (IEA, 2020).

The majority of existing energy efficiency measures in industry are voluntary, such as the Energy Champion programme, the Energy Intensity Reduction Agreement, and the Energy Management System (IEA, 2020). The main regulation for energy efficiency in industry is the Target Management System, which requires companies that emit over 50 ktCO2e (or 15 ktCO2e for individual businesses), to set a legally binding energy reduction target in consultation with the government.

In 2021 the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy launched the Green Steel Committee, which aims to align the domestic steel industry with South Korea’s climate neutrality target (Min-hee, 2021). At the launch, several major Korean steel manufacturers signed a joint statement for 2050 carbon neutrality, including POSCO, Hyundai Steel, Dongkuk Steel, KG Dongbu Steel, Seah Steel, and SIMPAC.

Transport

In 2019, the transport sector accounted for 18% of national CO2 emissions from fuel combustion (IEA, 2021a). The revised 2030 GHG roadmap intends to expand the supply of eco-friendly vehicles (including the supply of three million electric vehicles in 2030) (Ministry of Environment, 2018). In January 2019, the Korean Government also announced a roadmap for a hydrogen economy, setting goals of producing 6.2 million fuel cell electric vehicles and building 1,200 fuelling stations across the country by 2040 (MOTIE, 2019b).

The Green New Deal, announced in 2020, commits around USD 17bn to the development of eco-friendly vehicles and related infrastructure (Ministry of Economy and Finance, 2020). By 2025 the government plans to introduce 1.13 million electric cars, 200,000 hydrogen cars, and scrap 2.2 million old diesel cars.

South Korea is the world’s fifth largest car manufacturing country (OICA, 2019) and home to major companies such as Hyundai and Kia. In 2014, South Korea strengthened its light-duty vehicle emissions standard to 97 gCO2/km by 2020 (Transportpolicy.net, 2019), which is comparable to the EU’s new standards (95 gCO2/km) (ICCT, 2019).

Buildings

In 2019, the buildings sector accounted for 8% of national CO2 emissions from fuel combustion (aggregate of residential and commercial sectors) (IEA, 2021a). South Korea is gradually applying stricter energy conservation designs to meet zero-energy buildings standards for all new buildings by 2025 (APERC, 2019).

The 2030 GHG roadmap outlines several policies and measures for reducing emissions from the sector, including strengthening permit standards for new buildings, promoting green renovation, identifying new circular business models, and expanding renewable energy supply.

The Green New Deal commits around USD 4.5bn to green remodelling, which aims to ensure that new and renovated buildings are energy-efficient and constructed from sustainable materials (Ministry of Economy and Finance, 2020). By 2025 the Green New Deal plans to remodel 225,000 homes, 440 day-care centres, and 1,148 facilities.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter