Policies & action

Switzerland’s efforts to tackle climate change were struck a blow after the failure of its amended CO2 Act to pass in a June 2021 referendum. Under current policies, Switzerland is projected to miss even its less ambitious proposed domestic target of a 33% reduction below 1990 levels.

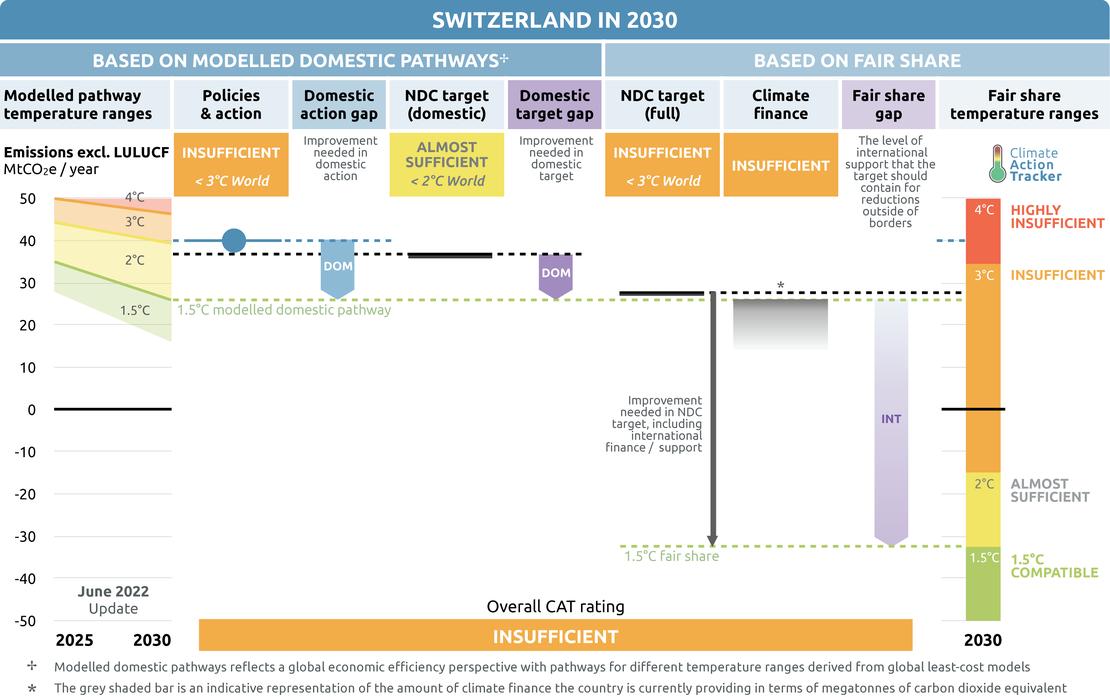

The CAT rates Switzerland’s current policies as “Insufficient” when compared to modelled domestic pathways. The “Insufficient” rating indicates that Switzerland’s climate policies and action until 2030 need substantial improvements to be consistent with the 1.5°C temperature limit when compared to its modelled domestic pathways. If all countries were to follow Switzerland’s approach, warming would reach over 2°C and up to 3°C.

Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against modelled pathways and fair share) can be found here.

Policy overview

Switzerland’s 2021 emissions were estimated to be 44 MtCO2e and are expected to reach around 40 MtCO2e by 2030 (excluding LULUCF), under its current policies. This projected reduction is lower than previous estimates as a result of the COVID-19 related economic slowdown, and are equivalent to a 19% and 25% reduction below 1990 levels, respectively (excluding LULUCF). Switzerland is therefore not projected to meet its currently proposed target of a 33% reduction in domestic emissions below 1990 levels under current policies. However, it may partially meet its overall NDC of a 50% reduction below 1990 levels through the use of carbon credits from international mechanisms.

In Switzerland’s 4th Biennial Report, released in December 2019, the implementation of all planned policies including the updated CO2 Act is projected to lead to a 35% reduction in total GHGs by 2030, enough to meet its current domestic target. This scenario has been removed from the present analysis, as it is not clear which of the previously planned measures will make it into the next iteration of Switzerland’s CO2 Act.

The rejected revision of the CO2 Act stated that its purpose was to limit the average increase in global average temperature to well below 2°C and pursue efforts to limit the temperature rise to 1.5°C. However, the emissions reduction targets included in this updated law were not aligned with what would be a fair-share, or least cost, effort to achieve this outcome.

The new proposed CO2 Act revision, released at the end of 2021 for public consultation, includes a number of weaker provisions than the original version (Swiss Confederation, 2021b). This includes a limitation of the carbon levy for the buildings sector to a maximum of CHF 120 (USD 130) which it is scheduled to reach already in 2022. New taxes are proposed to be avoided altogether in favour of tax incentives and funding instruments in the transport, buildings, and industry sectors.

The Swiss government’s reaction to the public referendum rejecting its target has been to propose reducing the domestic emissions target from 75% of the total target down to 60%, against the clear level of concern expressed by Swiss residents in a recent poll, where climate change was a close second to the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of the issues perceived to be most concerning (le News, 2021).

In October 2020, Switzerland and Peru signed a carbon credit agreement where Switzerland will finance emission reduction projects that are designed to contribute to sustainable development in Peru while the emissions reductions would count towards the Swiss NDC (Lo, 2020). In order to ensure environmental integrity, both Peru and Switzerland willhave to apply robust accounting systems so that the reductions are only counted once. Switzerland has subsequently signed similar agreements with Ghana, Senegal, Georgia, Vanuatu, and Dominica between late 2020 and the end of 2021 (IHS Markit, 2021).

Switzerland’s most relevant cross-sectoral climate policy is the carbon levy charged on fossil fuels. Due to a slower than expected decrease in emissions, the fee was increased in 2018 from CHF 84 (USD 91) to CHF 96 (USD 104) per tonne of CO2, From January 2022, it was raised to CHF 120 (USD 130) as emissions have not dropped sufficiently (Swiss Broadcasting Corporation, 2021). The combustion of different fossil fuels is charged depending on their emissions intensity, e.g. light heating oil is charged with CHF 254.40 for 1,000 litres whereas natural gas is charged CHF 255.40 for 1,000 kg of natural gas (Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, 2020a).

The majority of the proceeds from the levy is reimbursed to the citizens. Under the previous version of the CO2 Act, CHF 300m (USD 330m) of the remaining annual revenue was to be spent on emissions reduction in the building sector, and a further CHF 25m (USD 27.5m) on the Technology Fund (Der Bundesrat, 2012). In the most recent updated version of the CO2 Act this was raised to CHF 420m (USD 454m) per year with up to CHF 35m (USD 38m) to be made available for supporting geothermal energy projects for building heating (Swiss Confederation, 2021a).

Another cross-sectoral instrument influencing greenhouse gas emissions is Switzerland’s emissions trading scheme. Companies participating in the emissions trading are excluded from the obligation to pay the emissions levy. In March 2019, after two years of negotiations, the Swiss Parliament adopted a law linking the Swiss emissions trading scheme with the European EU ETS which came into effect on 1 January 2020.

While both systems continue to function separately, the emissions certificates can now be used interchangeably between the two systems (Bundesamt für Umwelt, 2019). After linking with the EU ETS, the price of Swiss emissions allowances broadly aligned with the higher EU allowance prices, which will accelerate emissions reductions by the emitters responsible for a third of emissions resulting from the combustion of fossil fuels (EEX, 2019; Swiss Federal Audit Office, 2017). In November 2019, the Federal Council expanded the scope of the Swiss ETS to include civil aviation and fossil-thermal power plants (ICAP, 2020).

The Swiss National Bank, in the face of pressure to use its investments to influence companies linked to climate change, has refused to implement green criteria for its investments. In response to calls for implementing criteria restricting investments into polluting companies, the bank maintained that such a shift would hurt its monetary policy and must maintain flexibility on how it invests its stores of foreign currency (Reuters, 2021).

Sectoral pledges

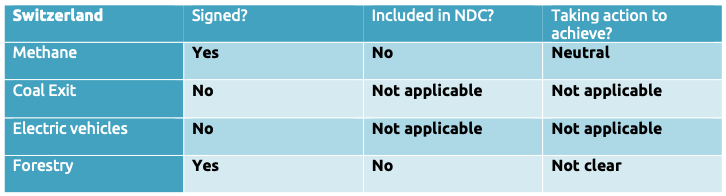

In Glasgow, four sectoral initiatives were launched to accelerate climate action on methane, the coal exit, 100% EVs and forests. At most, these initiatives may close the 2030 emissions gap by around 9% - or 2.2 GtCO2e, though assessing what is new and what is already covered by existing NDC targets is challenging.

For methane, signatories agreed to cut emissions in all sectors by 30% globally over the next decade. The coal exit initiative seeks to transition away from unabated coal power by the 2030s or 2040s and to cease building new coal plants. Signatories of the 100% EVs declaration agreed that 100% of new car and van sales in 2040 should be electric vehicles, 2035 for leading markets, and on forests, leaders agreed “to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030”.

NDCs should be updated to include these sectoral initiatives, if they aren’t already covered by existing NDC targets. As with all targets, implementation of the necessary policies and measures is critical to ensuring that these sectoral objectives are actually achieved.

- Methane pledge: Switzerland signed the methane pledge at COP26, a significant commitment given Switzerland’s significant agricultural methane emissions. A commitment to target a reduction in methane emissions has not, however, been included in Switzerland’s NDC, despite making up a tenth of Switzerland’s total GHG emissions in 2020 (Government of Switzerland, 2022). A 30% reduction in methane emissions below 2020 levels would represent a decline of 1.4 MtCO2e. There have been no recent policy developments to target further reductions.

- Coal exit: Switzerland has not adopted the coal exit agreement from COP26. However, there is no coal-fired power generation in Switzerland. Consequently, there is no mention of coal phase out nor a targeting of coal-related emissions in Switzerland’s NDC.

- 100% EVs: Switzerland did not adopt the EV pledge at COP26. This is despite seeing strong growth in EV sales in 2021, with Switzerland having an EV share of sales (22%) above the EU27 average (18%) (European Alternative Fuels Observatory, 2022b).

- Forestry: Switzerland signed the forestry pledge at COP26. Its most recent NDC does not refer to a specific target for forestry emissions, or for halting deforestation. It’s recently updated forest plan also does not include quantitative targets for reducing emissions from this sector or realising net negative emissions.

Energy supply

In 2020, over 97% of electricity in Switzerland was generated from renewable (62%, mostly hydro) or nuclear (35%) sources of energy, with the renewable share shown in Figure 1 (IEA, 2021). The Swiss power sector has been included in the ETS since 1 January 2020, but this only affects a small number of operators given the sector’s highly decarbonised nature.

Share of renewable electricity generation

In response to the COVID-19 crisis, waiting times for subsidies to solar PV projects were shortened with the intention of protecting the development of such renewable energy sources (Bundesamt für Energie, 2020c). A total of CHF 46m (USD 50m) has been made available to project planners, installers and local planning bodies. In addition, an exemption has been introduced for projects that would have been subjected to a lowering of remuneration rates from April 1 2020 due to COVID-19-related delays.

A May 2017 referendum adopted the Energy Strategy 2050, a package of measures aiming at increasing energy efficiency, reduction of CO2 emissions, and steadily replacing nuclear energy by renewables (Bundesamt für Energie, 2018a). Many of these measures were included in the reform of the Energy Law that went into effect in January 2018.

According to the law, nuclear energy is set to be steadily replaced by renewables, with the first nuclear plant having already been shut down in December 2019. By 2035 electricity generation from hydro power plants should remain at the current level of around 37.4 TWh. Electricity generation from non-hydro renewables should increase from around 3.3 TWh to 11.4 TWh in the same period. The law also sets the goal of decreasing electricity consumption by 13% below 2000 levels by 2035. It also introduces some changes to feed-in tariffs for renewables, including shortening the period during which installations receive the tariffs from 20 to 15 years (Die Bundesversammlung der Schweizerischen Eidgenossenschaf, 2018; VSE, 2019).

Industry

Most GHG emission reduction policies and measures affecting Switzerland’s industry sector are implemented under the CO2 Act and cover CO2 emissions from fossil fuel use. These include the CO2 levy on heating and process fuels, the Swiss emissions trading scheme, and the negotiated reduction commitments.

A number of key non-CO2 emissions, however, are not covered under the Act, and have been targeted separately. For example, a number of provisions relating to substances stable in the atmosphere cover all F-gases and are expected to result in a reduction of roughly 1.1 MtCO2e in emissions of such gases in 2020 (Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, 2020c).

Similar to the EU, Switzerland also uses an emissions trading scheme (ETS) to lower emissions from large energy intensive entities. However, the Swiss ETS is much smaller than the European ETS, not only because of the smaller market but also due to the fact that the emissions generated by 54 companies in the power, cement, pharmaceutical, refinery, paper, district heating, and steel sectors covered by the scheme represent only 10% of the country’s emissions. Emissions from the sector were capped in 2013 at 5.63 MtCO2, and required to be reduced by 1.74% per year in order to reach a target of 4.91 MtCO2 in 2020 (13% reduction on 2013 levels) (Mission of Switzerland to the European Union, 2017). From 2021, the annual required rate of reduction rose to 2.2% of the 2010 baseline, which applies until 2030 (Federal Office of the Environment, 2020).

To deal with the allowances’ price volatility, in 2011 the European Commission and Swiss government opened negotiations on linking both carbon markets. While the price of allowances has been increasing in the EU ETS and averaged over EUR 25 in 2019, the price of Swiss allowances fell from CHF 40 (USD 44) in 2014 to CHF 8 (USD 8.8) in 2018. In March 2019, the Swiss Parliament adopted a law linking the Swiss emissions trading scheme with the European EU ETS (Bundesamt für Umwelt, 2019), and as a result, the price of Swiss allowances rose to CHF 18.2 (USD 20) by the end of 2019 (Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, 2020b). The schemes were officially linked on 1 January 2020 and this is likely to ensure high allowance prices in the Swiss ETS moving forward.

Transport

Emissions from the transport sector were responsible for over 31% of Switzerland’s total GHG emissions in 2020 (excl. LULUCF), and until 2008, emissions from this sector increased to 13% above 1990 levels (Government of Switzerland, 2022). Since then, they have been steadily decreasing and in 2020 they fell below 1990 levels for the first time since 1996, primarily due to lower car travel during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In response to the COVID-19 crisis, the aviation industry received bank guarantees of almost CHF 2 bn with the requirement that the aviation companies cooperate in the development of future climate policy (Schweizer Parliament, 2020b). The Federal Council failed to pass other, more concrete and binding requirements. For example, a stipulation that airlines must reduce their emissions in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement was rejected, as was a condition that emergency funds received must be used in a way that contributes towards the achievement of net-zero emissions. A proposal requiring airlines to participate in the development of sustainable e-fuels was also rejected.

The inclusion of domestic and international aviation between Switzerland and member states of the European Economic Area (EEA) into Switzerland’s ETS since 1 January 2020 is a significant policy development, with emissions from the sector in the scheme to be capped at 2018 levels (Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, 2020c). In addition, starting from 2020 for new designs, and from 2023 for in-production models, aircraft in Switzerland will be subject to CO2 emission targets. Switzerland has indicated its intention to participate in the carbon offsetting and reduction scheme for international civil aviation (CORSIA), under which emissions are capped at 2019 levels. Applicable standards and recommended practices for the scheme are currently being prepared by the International Civil Aviation Organisation, with the pilot phase beginning in 2021. This scheme has significant shortcomings, meaning it is unlikely to deliver the substantial reductions needed to achieve the ICAO’s aspirational goal of carbon neutral growth from 2020.

After a continuous decrease in average emissions intensity of passenger cars from 198 gCO2/km in 2002 to 134 gCO2/km in 2016, it rose for three consecutive years, reaching 138 gCO2/km in 2019 (Bundesamt für Energie, 2020a). In 2020, with sales of electric vehicles beginning to climb, this fell by over 10% to 124 gCO2/km (Bundesamt für Energie, 2021a). The emissions intensity of light commercial vehicles have fallen 17% since data collection began in 2011, reaching 176 gCO2/km in 2020. Both values are significantly above the average of European passenger and light commercial vehicles, which were 122.4 and 158.4 gCO2/km, respectively in 2019 and almost certainly declined in 2020 (European Commission, 2020).

In 2012, Switzerland adopted a regulation that included the goals of reducing emissions for newly-registered passenger cars to 130 gCO2/km, in alignment with EU vehicle emissions regulations (Swiss Federal Office of Energy, 2019). Since 2020, as with the latest EU regulations, the emissions of new cars cannot exceed 95 gCO2/km. The emissions reduction goal for vans and light trucks is 147 gCO2/km from 2020 onwards. The previous amendment of the CO2 Act introduced an emissions reduction target for the period after 2025: between 2025 and 2029 emissions of passenger vehicles should be 15% lower than in 2020. By 2030 this reduction should – like in the case of the EU – decrease by 37.5% below the 2021 value, with vans and light duty trucks required to be 31% below the 2021 value.

Emissions from heavy duty vehicles were to decrease by 30% between 2020 and 2030 (Schweizer Parlament, 2020a). The prescriptions targeting light duty vehicles have been kept, while the target for heavy duty vehicles has been scrapped in the latest version of the amended CO2 Act. Car importers exceeding those limits were to be required to pay a penalty of between CHF 95 and 152 for each gCO2/km they exceed.

Despite the clear need to take more action to reduce emissions from passenger and commercial vehicles, the penalty for exceedance of emissions limits was decreased for the fourth and each following gCO2/km of exceedance from CHF 142.50 to 104.50 (Bundesamt für Energie, 2018b). This will reduce the costs of purchasing inefficient and carbon-intensive vehicles.

Although the average cost of exceedance was reduced in this manner, the total penalties paid by importers has risen dramatically since 2017 due to the increasing average fuel consumption of new vehicles. In 2017, total penalties paid by importers was CHF 2.9m, rising to CHF 78.1m in 2019, and CHF 132m in 2020, with the average penalty per vehicle in 2020 totalling CHF 556 (Bundesamt für Energie, 2020b, 2021b).

Given the very low emissions intensity of Switzerland’s power sector, a shift to electric mobility has a disproportionately high impact on overall emissions reductions. In 2021, over 22% of all new passenger cars in Switzerland were electrically chargeable vehicles, which includes battery-only (13%) and plug-in hybrid (9%) vehicles (European Alternative Fuels Observatory, 2022a).

Although the uptake of electric vehicles is accelerating, their share of new sales in Switzerland remains significantly below that of some countries with a comparable level of income that make electric cars more affordable (e.g. 45% in Sweden, 31% in Finland, 86% in Norway in 2021), and only slightly higher than the EU27 average in 2021 of 18% (European Alternative Fuels Observatory, 2022b). However, the share of battery electric vehicles in total car sales alone in 2021 (13%) almost reached the 15% target for 2022 outlined in its Roadmap for Electric Mobility 2022 (Bundesamt für Energie & Bundesamt für Strassen., 2018). Such strong sales already in 2021 demonstrates that the target is unambitious.

The share of freight transported by rail in Switzerland in 2020 was, at 37%, much higher than in the EU, which was 18% in 2019 (Bundesamt für Statistik, 2021). However, it was significantly below the share of freight transported by rail in this country in the 1980s (around 53%). This decreasing trend was especially clearly noticeable in 2017 when the number of products transported by rail decreased by 7% while the number of products transported by road increased by 1.5% (Bundesamt für Statistik, 2018).

The previous revision of the CO2 Act introduced a levy on airplane tickets at between CHF 30 (USD 32) and CHF 120 (USD 130), however this was scrapped in the current proposed revision (Schweizer Parlament, 2020a; Swiss Confederation, 2021a).

Buildings

In 2020, the buildings sector, including services and households, was responsible for roughly 24% of Switzerland’s total GHG emissions (excl. LULUCF), a decrease compared to 1990 when they represented around 32% of the country’s emissions (Government of Switzerland, 2022). This has been the result of emissions in this sector decreasing much faster – by 37% between 1990 and 2020 - than in the case of the overall emissions. However, this decrease was still not enough to meet the goal of a 40% reduction in emissions below 1990 levels by 2020 that was adopted in the 2012 CO2 Regulation (Der Bundesrat, 2012).

The rejected CO2 Act included an extension of this target, requiring cantons to develop building standards for new and existing buildings to ensure total buildings emissions are 50% below 1990 levels by 2026/27 (Schweizer Parlament, 2020a). In addition to this, fossil fuel heating systems were to be banned for use in new buildings from 2023, while replacement heating systems in 2023 would not have been permitted to emit more than 20kgCO2/m2 of building space, which was to be further reduced by 5kgCO2/m2 in each subsequent year.

All of these measures have been scrapped in the amended proposal and replaced with funding instruments to encourage adoption of heat pumps and the creation of district heating networks, but with no sector-wide emissions reduction target (Swiss Confederation, 2021a). An increase in the funding for building heating upgrades in the previously amended CO2 Act to CHF 450m (USD 486m) has been maintained in the current proposal.

Energy efficiency standards for buildings are decided at the regional level, while municipalities are allowed to introduce even stricter standards (Immopro, 2017). In 2014, the regional governments agreed on a new standard - called MuKEn14 – to be implemented by all regions before 2018, which became binding in 2020. For new builds, the standard amounts to 35 kWh/m2 for single and multi-family houses. For warehouses, the standards are even stricter and should not exceed 20 kWh/m2. Each house should also be equipped with a renewable source of power amounting to at least 10 W/m2 of the living space (EnFK, 2014).

These targets have already been met by some of the buildings complying with the Swiss “Minergie” standards. There are three major categories: Minergie houses should not consume more than 55 kWh/m2 for new single houses and 90 kWh/m2 for renovations. For Minergie-P the standards are 50 kWh/m2 and 80 kWh/m2 respectively. For Minergie-A the standards are 35 kWh/m2 for both, new builds and renovations. By April 2022, there were over 53,000 Minergie certified buildings in Switzerland (Minergie, 2022).

Agriculture

Emissions from the agriculture sector in 2020 constituted around 13% of total emissions (excluding LULUCF) – representing a roughly constant share of total emissions as they have been decreasing at around the same pace as overall emissions (Government of Switzerland, 2022).

The Climate Strategy Agriculture aims to reduce agricultural emissions by at least one third by 2050 with technical, operational, and organisational measures, and by another third with measures influencing food consumption and production (Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, 2020c). It includes both mitigation and adaptation to climate change in the agricultural sector.

Switzerland’s Agricultural Policy 2014-2017 and 2018-2021 contains the abolition of unspecific direct payments (livestock subsidies, general acreage payments), additional funds for environmentally friendly production systems, and for the efficient use of resources (e.g. increase in nutrient efficiency and ecological set-aside areas, reduction of ammonia emissions). It is expected to result in reductions of 0.2 MtCO2e in 2020 (Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, 2020c). Discussions on a successor to the 2018-2021 policy called AP22+ were placed on hold until Spring of 2023 at the earliest (Swiss Government, 2021a).

Forestry

Except for a few select years, forestry constitutes a sink of emissions in Switzerland of between 1-4 MtCO2 annually (Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, 2020c). Under current policies, however, this is expected to change, with the sector projected to become a source of emissions between 2020 and 2030 of roughly 1 MtCO2e per year. In 2020, 31% of Switzerland’s total area was covered by forests, roughly the same percentage since 2017 (Government of Switzerland, 2022).

The Forest Policy 2021-2024 aims to coordinate the ecological, economic and social demands on forests, managing forests in a sustainable manner. It includes a long-term target of a CO2 balance between forest sink, wood use and wood substitution effects. Given the current age structure of Swiss forests, this implies aiming at increased harvesting rates over the coming years. The targeted annual mitigation impact of the Forest Policy 2021-2024 is 1.2 MtCO2e (Bundesamt für Umwelt, 2021).

Waste

Emissions from the waste sector in Switzerland made up roughly 2% of total GHG emissions (excluding LULUCF) in 2020 and registered an absolute decrease of almost 40% between 1990 and 2020 (Government of Switzerland, 2022). Since 2000, the disposal of untreated municipal waste into landfill has been prohibited, with an increase in the capacity of waste incineration plants implemented to accommodate this ban (Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, 2020c). These incineration plants have substantially reduced methane emissions from Swiss landfills and produce roughly 2% of Switzerland’s total energy consumption.

A further measure in the waste sector is the ordinance on the avoidance and management of waste, implemented in 2016, which promotes closed-loop material flows. While a large proportion of Switzerland’s municipal solid waste is already recycled (53% in 2015), further improvements could be made in the reduction of environmental pollution and strengthening the reliability of the waste removal system as a whole (Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, 2018).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter