Country summary

Assessment

Turkey is at a crossroads with regards to its energy future: current government plans foresee decreasing its dependency on gas imports through both the use of domestic lignite coal, with still 34GW in the pipeline, and renewable energy sources. Although Turkey’s emissions will increase under current policies, it will overachieve its "Critically Insufficient” – but not yet ratified – INDC, which is so weak that it allows GHG emissions to double compared to current levels.

Coal-fired power plants receive increasing criticism from the population, and the coal pipeline, while still huge, has decreased in the last year. Meanwhile, costs for renewables in Turkey are at record lows, which brings into question the economic attractiveness of further embarking on fossil energy.

The Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources announced in May 2019 it was holding tenders for coal mines promoting domestic lignite, and the long-delayed 1.3 GW Hunutlu thermal power plant construction was launched in September 2019 despite being in a biological preservation zone. This stands in strong contrast to Turkey’s need to reduce the use of coal in electricity by close to zero by 2030.

While the stated aim for this coal expansion is improved energy security, water shortages in the region are already casting doubt on the operating efficiency, output and reliability of thermal power plants, and these stresses are expected to intensify. Turkey has also begun constructing its first nuclear power plant amid international protest at the earthquake risk, but its Japanese-French nuclear power plant project was cancelled in June 2019.

The ongoing reduction in the costs of renewable energy technology and storage means that reliable power can be obtained cost-effectively without resorting to coal-powered generation. In fact, installation costs of solar photovoltaic in Turkey are among the lowest in the world.

However, while Turkey already achieved its National Renewable Energy Action Plan Solar Energy Capacity Target (5 GW by 2023), there is a slowdown in its wind power installations (approaching 7.4 GW at year’s end), throwing wind energy capacity goals into doubt (20 GW by 2023). In its recently published 11th development plan (July 2019), Turkey has increased its renewable electricity generation target from 30% to 38.8% by 2023, but should consider setting longer-term renewable energy targets. The Turkish government has also committed to investing almost US$ 11 billion in energy efficiency measures and its National Energy Efficiency Action Plan, if fully implemented, is expected to reduce Turkey’s emissions by 14% below current policy projections by 2030.

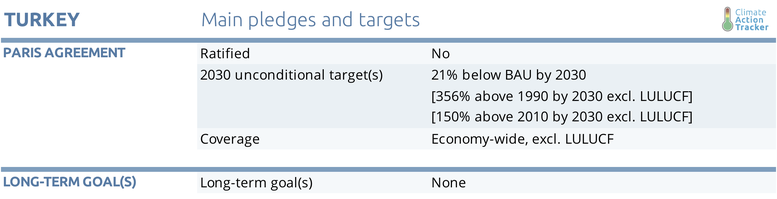

Aside from the Energy Efficiency Action Plan and renewable energy auctions with varying levels of enforcement, Turkey has made little progress on climate action implementation. It still hasn’t ratified the Paris Agreement. In September 2019, prior to the UN Climate Summit, Turkey has been analysing the financial package proposed by Germany and France with the support of U.N. and the World Bank supposed to answer Turkey’s concerns by ratifying the agreement but with no outcomes so far. The government appears to be standing still in developing measures that might reduce its GHG emissions: its 7th National Communication (NC7) projections in 2018 have identical projections as the previous version (NC6) as well as the 2015 INDC BAU. However, the NC7 describes more precisely the policies included within the NC6.

For full details see pledges and targets section.

Turkey remains the only G20 country that has not ratified the Paris Agreement. Excluding LULUCF emissions, the target in the INDC is equivalent to a 90% increase from 2017 levels (latest historical year included in our analysis).

We rate Turkey’s INDC target “Critically Insufficient”. Turkey’s commitment is not in line with interpretations of a “fair” approach in line with holding warming below 2°C, let alone with the Paris Agreement’s stronger 1.5°C limit. This means that if most other countries followed Turkey’s approach, global warming would exceed 3–4°C.

In the recently published 11th development plan, Turkey’s primary energy demand is expected to increase of 18% by 2023 above 2018 levels, and it targets an increase of electricity production from domestic sources (including coal) of 46% by 2023 above 2018 levels. 2018 saw the commissioning of two new power plants in Turkey (Yumus Emre and Çan-2), the Soma Kolin Power Plant, totalling 1.2 GW of additional capacity, started operations in June 2019, and recently started the construction of the long-delayed 1.3 GW Hunutlu thermal power plant although it has faced difficulties in obtaining a permit, as it is located in a biological preservation zone. The government is continuing to press for large expansion in coal power with close to 34 GW of planned power plants (announced, pre-permitted and permitted) and 2018 saw Turkey breaking its record in domestic coal production, which reached 101.5 million tonnes.

Turkey is also embarking on building Nuclear Power Plants (NPP), having announced that three NPP will come into operation between 2023 and 2030. The first, a four unit 4.8 GW NPP at Akkuyu, is the result of a partnership with Russia’s Rosatom. The foundation from its first unit (1.2 GW) was completed in May 2019 and this unit is expected to be fully operational by 2023. The full four-unit NPP is expected to be operational by 2025. The European Parliament recently voted against the construction of the Akkuyu plant, calling for the inclusion of neighbour countries in the process and pointing out the risks of severe earthquakes in that region.

Although the second NPP at Sinop in Northern Turkey is facing difficulties after the Japanese construction partner withdrew from the project, the government is still planning on its construction, but has yet to announce new partners and funders. Discussions are underway with Chinese interests for the third NPP.

In 2016, the government introduced the Renewable Energy Resource Areas (YEKA) strategy, a tender process to procure the production of renewable energy on ‘Renewable Energy Designated Areas,’ (REDAs). The first auction in March 2017 was awarded for a solar PV power plant production, but construction has not yet started. A 1 GW wind onshore was awarded by auction in August 2017 and the turbine factory in the Aegean city of Izmir is expected to be up and running by the end of 2019. A third wind onshore auction (1 GW) has recently (May 2019) been awarded to the German-Turkish consortia (Enercon-Enerjisa).

While there was a successful tender process in 2017 (1 GW Solar and 1 GW Wind Auctions), the 1.2 GW off-shore wind auction initially announced for June 2018 and postponed to 2019 has not yet taken place. This was followed by the cancellation of the second solar PV YEKA auction, originally planned for January 2019. The last auction to be recorded was awarded in May 2019 for a 1 GW Onshore Wind Tender to Enercon-Enerjisa Consortium (Presidency of The Republic of Turkey, 2019). So even though the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources has new plans to install an additional 10 GW of solar PV and 10 GW of wind capacity in the coming decade, and prices from recent auctions show a very competitive renewable energy sector, if the delays for renewables experienced so far were to continue, we are not confident this timeline will be met, and periods of policy uncertainty refrain investors and industry actors which is harmful to job creation (IRENA, 2019a) . On the positive side, if Turkey achieves its plan to increase its installed capacity in wind and solar energy by almost 21 GW by 2024, it will be among Europe’s five top countries for the amount of renewables.

Due to its strategic location and the forecasted increasing demand on Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) worldwide, Turkey is continuing its efforts to become a gas trading hub by developing its storage and regasification capacities: two new floating storage and regasification units (FSRU) planned by 2023 when the second FSRU was commissioned in January 2018. From January to June 2019, the country’s imports reached a record high and in 2018 LNG imports represented 22.5% of total gas purchased. The CAT, however, cautioned in June 2017 that natural gas has a limited role to play as a bridging fuel in the power sector and runs the risk of overshooting the Paris Agreement long-term temperature goal if fully operational or creating stranded assets.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter