Policies & action

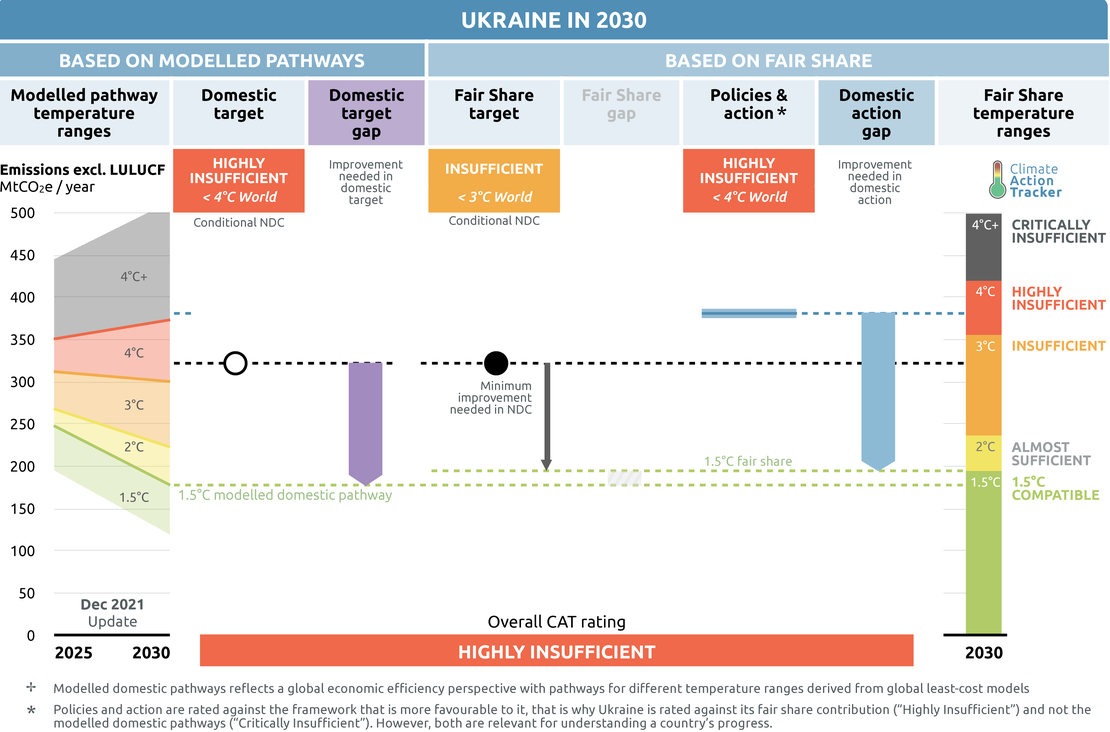

We rate Ukraine’s policies and actions as “Highly insufficient” when compared to their fair share contribution. The “Highly insufficient” rating indicates that Ukraine’s policies and action in 2030 lead to rising, rather than falling, emissions and are not at all consistent with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C temperature limit. If all countries were to follow Ukraine’s approach, warming could reach over 3°C and up to 4°C.

In our rating methodology, we rate a government’s policies and action against the framework that is more favourable to it – fair share or modelled domestic pathways. Ukraine’s policies and action rate more favourably in comparison with its fair share contribution (“Highly insufficient”) than modelled domestic pathways (“Critically insufficient”), hence the former is incorporated into Ukraine’s overall rating, but both are relevant for understanding the country’s progress.

Ukraine’s planned policies would let emissions stabilise roughly at today’s level. If we were to rate the planned policies, we would rate them “Insufficient”, moving closer to a 2°C compatible pathway but it would still require substantial additional measures to be in line with a 1.5°C Paris-compatible pathway.

Policy overview

Between 1990 and 2000, emissions in Ukraine dropped by 55% from 942 MtCO2e to 427 MtCO2e excl. LULUCF. From 2001 to 2007, emissions started to increase again moderately, followed by a steep decline during the financial crisis in 2009 and further declines in recent years as a result of the conflict in Eastern Ukraine. The CAT estimates that Ukraine’s 2020 emissions (excl. LULUCF) were 66% below 1990 levels excl. LULUCF or 319 MtCO2e in total. That is 13 MtCO2e or 4% less than in 2019.

Currently implemented policies and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic are expected to lead to an emissions level of 375-386 MtCO2e excl. LULUCF in 2030, which is above the NDC target of 323 MtCO2e excl. LULUCF. Planned policies would lead to an emissions level of 282-290 MtCO2e excl. LULUCF in 2030, overachieving Ukraine’s NDC target.

In July 2021, Ukraine submitted its updated NDC to the UNFCCC. The submission targets a 65% reduction below 1990 levels by 2030 including LULUCF, a significant improvement on its previous target of at least a 40% reduction below 1990 level by 2030, and for the first time includes an announcement of climate neutrality no later than 2060 (The Government of Ukraine, 2021).

The updated NDC was developed with a team of national and international experts, including broad public participation through a working group comprised of representatives of all relevant ministries, scientific institutions, business associations and non-governmental organisations, and is substantiated by an analytical review and modelling report.

Ukraine is in a difficult situation, as it struggles to access sufficient climate finance. The modelling undertaken to derive Ukraine’s NDC indicates total financing needs of around EUR 540bn in the period 2020-2030 for implementing Ukraine’s updated NDC (IEF, 2021). Since Ukraine is an Annex I country, it is not eligible for GCF financing, although its GDP per capita is among the lowest in Europe and below those of many countries which have received funding from the GCF in the past (Lo, 2021). Since it is also not a member of the EU, Ukraine is also not eligible for initiatives like the Just Transition Fund, which is helping coal-reliant countries like Poland to move away from fossil fuels.

Ukraine’s ongoing war with Russia and economic recession are major hurdles to overcome and the COVID-19 pandemic has additionally severely impacted Ukraine’s economy, leading to a drop in greenhouse gas emissions and accelerating the country’s energy crisis which had slowly been building for years. The quarantine measures enacted slowed down the country’s economic activity, and GDP dropped by 8.2% in 2020 (IMF, 2021). Both energy demand and production had been decreasing and brought the power sector payment regime to the verge of collapse (Prokip, 2020).

In May 2020, the Ukrainian government approved the Economic Stimulus Programme to help stabilise the economy in light of the COVID-19 pandemic (Government of Ukraine, 2020a). The programme included a number of short and medium-term measures for supporting Ukraine's economy for the period 2020-2022. While the document mentions optimising the environmental tax to promote eco-friendly modernisations, links to climate and environmental policy are not only limited, but money from the economic stimulus funds could even be used for restructuring the coal industry to save mining jobs (Government of Ukraine, 2020a; 350.org Ukraine, 2020; Zasiadko, 2020).

Indeed, in June 2020, the Cabinet of Ministers adopted an order prioritising coal use in Ukraine’s power sector, aiming to strengthen the domestic coal industry and preserve 20,000 mining jobs (Government of Ukraine, 2020c). The Ukrainian government should take into consideration that if low carbon development strategies and policies are not rolled out in the economic stimulus package, emissions could rebound and even overshoot previously projected levels by 2030, despite lower economic growth (Climate Action Tracker, 2020).

In March 2020, more than two-thirds of the Cabinet of Ministers were dismissed, which left the Ministry of Energy and Environmental Protection with an interim minister and no clear policy direction for the energy sector (Krynytskyi & Savytksyi, 2020). In April 2021, the Ukrainian parliament appointed Herman Halushchenko, vice president of Ukraine’s state nuclear operator Energoatom, as the new minister (Polityuk & Zinets, 2021). At his first working meeting, Halushchenko outlined his priority tasks: stabilising the energy system, adopting an effective market model that provides affordable electricity for citizens and profits for energy companies, integration in the European market and diversification of energy supplies as well as restructuring the coal industry to drive decarbonisation efforts (Polityuk & Zinets, 2021).

Ukraine is also looking to attract national and international investments for tapping natural gas reserves in its onshore blocks and in the Black Sea. In December 2020, Ukrainian authorities granted state-owned gas company Naftogaz a 30-year exploration and development licence for a large area in the Black Sea, with production set to start in 2024 (Afanasiev, 2021; Hornby, 2021). While locally-produced gas would lower Ukraine’s dependence on Russia, the country should rather focus on increasing its renewable energy generation to move towards a Paris-compatible pathway and avoid technology lock-in and the risk of stranded assets.

The ongoing cost reduction of renewables and the development of battery storage and renewable hydrogen will lead to the disruption of business models for gas-fired power plants in the longer term. This could result in higher electricity costs for customers if Ukraine were to invest in new natural gas projects (Krynytskyi & Savytksyi, 2020).

In January 2020, the Ministry of Energy and Environmental Protection published Ukraine’s 2050 Green Energy Transition Concept (Ukraine Green Deal) and presented it to EU officials as the country’s to meeting the objectives of the European Green Deal (Ministry of Energy and Environmental Protection Ukraine, 2020b; Mitsovych et al., 2020). It was the first Ukrainian strategy document that integrates climate and energy policy and that is based on the long-term energy system model developed for the second NDC (Mitsovych et al., 2020). To become effective, the concept will still need to be supported by concrete policy measures through the National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP), which was expected in 2020 but in September 2021 was still not finalised (EU4Climate, 2021).

Overall, the concept focuses on reducing GHG emissions through improving energy efficiency and boosting the deployment of renewable energy. While this is a step in the right direction, the document sets a 70% target for renewable energy by 2050, while modelling done in 2017 showed that Ukraine could reach a 91% renewable share by the same date (Diachuk et al., 2017; Morgan, 2020).

In July 2018, Ukraine published its 2050 Low Emission Development Strategy. This strategy provides emission reduction pathways for the energy and industry sectors based on four scenarios containing different ambition levels of decarbonisation measures and policies. The Ministry of Energy and Environmental Protection indicated that an update of the strategy together with Ukraine’s Green Deal, published in January 2020, might replace the current Energy Strategy of Ukraine 2035 (Mitsovych et al., 2020).

Since 2011, Ukraine has a carbon tax that applies to CO2 emissions from stationary sources in the industry, power, and buildings sectors. In November 2018, the Ukrainian parliament decided to steadily increase the carbon tax rate (currently 0.02 USD/tCO2) from January 2019 onwards. But even with this increase the rate remains far below 1USD/tCO2 in 2021 and still is among the lowest carbon prices in the world, and therefore unlikely to have an impact (Ministry of Finance of Ukraine, 2018; World Bank Group and Ecofys, 2018). New instruments for taxing carbon emissions are currently being discussed by the Ukrainian government, with one of the options being fuel-based taxation, i.e. taxing primary energy production and imports (Mitsovych et al., 2020).

Energy supply

The energy sector is responsible for 66% of Ukraine’s total emissions excluding LULUCF.

The electricity sector is responsible for roughly 45% of the total projected emission reductions until 2030 under Ukraine’s updated NDC. Modelling shows that to achieve these emission reductions and simultaneously create a well-functioning electricity system, investments of approximately EUR 27bn will be needed in the energy sector until 2030 (Low Carbon Ukraine, 2021).

In 2017, Ukraine updated its energy strategy through to 2035 (Government of Ukraine, 2017a). The strategy set new targets for electricity generation from different energy carriers. In 2035, 25% of electricity generation is projected to come from renewable energy sources including hydropower (2015: 4%), 25% from nuclear power (2015: 26%), and 50% from coal, natural gas and oil products (2015: 70%). However, a step-by-step implementation plan has not been developed.

Between 2018 and 2020, the installed capacity of renewable energy excluding hydropower significantly increased from around 2 GW at the end of 2018 to almost 9 GW at the end of 2020 (IRENA, 2021). In 2020, Ukraine added 1.4 GW of solar PV capacity, reaching a total of 7.3 GW, an increase of 23.5% compared to 2019 (and 771% since 2015) (IRENA, 2021). Total wind capacity at the end of 2020 stood at 1.4 GW with 144 MW added during the year. However, electricity generation from renewable sources still makes up only 8% of Ukraine’s total generation, significantly lower than the EU average of 39%, as illustrated in the graph below.

Renewable energy support schemes

Since 2008, Ukraine has had a feed-in-scheme in place with fixed prices, called the "green" tariff for electricity. The green tariff ensures that all generated renewable power is fed into the grid. The feed-in tariffs (FiT) were initially established at relatively high rates: 0.47 USD/kWh for rooftop solar PV under 100 kW and 0.12 USD/kWh for wind projects with capacity greater than 2 MW and continuously adjusted to market levels in the following years (International Energy Agency, 2017).

The green tariff was very successful: in 2019 alone, national power companies, foreign and Ukrainian investors poured USD 4.5bn into the construction of wind and solar power capacity to take advantage of the generous tariff (Prokip, 2020). However, the government had only budgeted to buy roughly half of the renewable power that companies were expected to produce in 2020 and, since March 2020, the government has put payments on hold and is trying to retroactively reduce the “green tariffs”, which would cause significant corporate losses, putting the whole renewable energy industry at risk (Kossov, 2020; Prokip, 2020).

In June 2020, the Cabinet of Ministers signed a memorandum with renewable energy producers, stipulating that they accept the conditions for the voluntary restructuring of the green tariff. Tariffs for solar power and wind power facilities were retroactively cut by 15% and 7.5%, respectively, for plants commissioned in the period 2015-2019 and by 2.5% for solar and wind power plants commissioned from January 2020 (Government of Ukraine, 2020b). Ukrainian authorities committed to taking every measure to ensure the timely payment to the Guaranteed Buyer and the repayment of debts to RES producers who have agreed on the terms of the restructuring (Government of Ukraine, 2020b).

Due to concerns about the financial sustainability of the existing support scheme, a law introducing a new scheme based on competitive capacity auctions for renewables was signed into law in May 2019 (Mykhailenko et al., 2019; Savitsky, 2018). In August 2021, the Ministry of Energy and Environmental Protection published a draft law on setting up an auction scheme for large-scale renewables (Ministry of Energy and Environmental Protection, 2021b). Under the new regulations, technology-neutral feed-in premiums would be paid to renewable energy plant operators, in addition to the wholesale electricity price under contracts for difference (Bellini, 2021). In December 2020, the Ministry of Energy suggested holding auctions for 155 MW solar PV and 150 MW wind capacity in 2021, with 170 MW for each solar PV and wind to follow in 2022, 180 MW solar and 190 MW wind in 2023, 190 MW solar and 210 MW wind in 2024, and 200 MW solar and 230 Wind in 2025.

Electricity market measures

Ukraine opened its electricity wholesale market in July 2019. Market regulations continue to adjust financial flows in the system, requiring large energy companies to provide more electricity at low prices to the Guaranteed Buyer (GB) so that the GB can use increased profits to finance renewable support costs from the transmission tariff (Mykhailenko & Temel, 2019). Ukraine was, however, neither technically nor legally prepared for the new electricity market and in June 2020 interim Minister of Energy, Olga Buslavets, reported that the GB was roughly half a billion USD behind in payments to renewable electricity producers (Prokip, 2020).

Despite taking steps in the right direction, Ukraine continues to face a severe energy crisis, one that has been building for years due to a lack of long-term energy policy planning and was accelerated by the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, putting the entire renewable energy industry at risk. In April 2020, the cumulative debt in the electricity market amounted to about USD 1.87bn and roughly the same for the gas market (Prokip, 2020). In June 2020, the Ukrainian parliament passed a bill (No. 2386) on debt settlement in the electricity market. In 2021, however, Ukraine is still far behind in its debt repayments, which could, in the short term, lead to 15% to 18% in additional penalties on top of the existing debt (Bondarchuk, 2021).

The new policy instrument on renewable capacity auctions, currently under public discussion, aims to resolve the liquidity issues surrounding the GB and follows the commitments under the memorandum between the Cabinet of Ministers and Ukraine’s renewable energy producers from June 2020 (Radchenko, 2021). Ukraine’s Electricity Market Law of June 2017 aims at aligning Ukraine’s national legislation with the regulation from the European Union’s Third Energy Package on the European gas and electricity markets through which Ukraine’s national electricity market will be liberalised (Government of Ukraine, 2017b; IEA, 2017). This includes separating companies according to distribution and transmission of electricity (Kiyv Post, 2017).

The integration of Ukraine’s power transmission system with the EU is under development and a priority under the new minster of energy and environmental protection. In April 2018, the national transmission system operator Ukrenergo announced—following an earlier announcement in June 2017 on full integration with the European Network of Transmission System Operators Electricity (ENTSO-E) by 2025—the support of full-scale deployment of renewables in Ukraine and investments in grid modernisation (Savitsky, 2018).

Coal phase-out

In November 2021, at COP26 in Glasgow, Ukraine announced it would bring its coal phase-out date forward from 2050 to 2035 as part of becoming a member of the Powering Past Coal Alliance (PPCA, 2021). In addition, DTEK, the biggest private investor in Ukraine's energy sector has also joined the Powering Past Coal Alliance, committing to powering operations without coal by 2040.

This is a substantial improvement to the initial phase-out date set under the Green Energy Transition Concept and an important step forward for Ukraine, the country with the third largest coal fleet in Europe. However, the commitment needs to be substantiated with a concrete phase-out plan and not yet fast enough to be compatible with the 1.5°C temperature limit. In Paris Agreement-compatible pathways for Eastern Europe and Former Soviet Union countries, coal power generation would need to be reduced by 86% by 2030 below 2010 levels, leading to a phase-out by 2031 (Yanguas Parra et al., 2019).

Industry

The industry sector is responsible for 18% of Ukraine’s total GHG emissions excluding LULUCF. However, a significant part of energy sector emissions are also related to industry.

In January 2018, Ukraine’s environment ministry published a draft law that will require large emitters to audit their emissions as an initial step towards Ukraine developing a functioning Emission Trading System (ETS). This was initially intended for commencement in 2020 but in 2021 the Minister of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources indicated that the ETS would not start before 2025 (Carbon Pulse, 2018; ICAP, 2021). The draft law contains no information on the emissions threshold for installations, but sets out plans for a government registry, third party verification, and a process for companies to devise emissions monitoring plans. Industrial production decreased in the last quarter of 2019, leading to a drop in energy demand by early 2020 and resulting in the suspension of operations at the biggest Ukrainian private coal mine in April 2020 and COVID 19 quarantine measures had slowed down activity even further (Prokip, 2020).

There are currently no explicit policy measures in place to stimulate the modernisation of Ukraine’s industry or to boost energy efficiency, particularly due to high up-front costs and given that the unstable investment climate in Ukraine makes it difficult for the sector to attract sufficient funds (Ministry of Energy and Environmental Protection Ukraine, 2021).

However, the draft National Action Plan on Energy Efficiency 2030 foresees an increase in energy efficiency by introducing financial incentives for industrial enterprises, and using revenues from the carbon tax to provide loans to implement relevant measures (Ministry of Energy and Environmental Protection Ukraine, 2021). It is unclear, however, whether the envisaged carbon tax increase (UAH 30/tCO2 (EUR 0.9/tCO2) by 2024) will be sufficient to secure additional funds.

Transport

The transport sector is responsible for about 11% of Ukraine’s total emissions excluding LULUCF: sector emissions have been on an upwards trajectory since 2015. The 2030 National Transport Strategy of Ukraine set a target of 60% emissions reduction below 1990 levels, although the sector had already achieved a 69% reduction in 2017. The updated NDC has only slightly increased this target to 68% emission reductions compared to 1990, keeping emissions more or less stable at today’s levels (Ministry of Energy and Environmental Protection Ukraine, 2021).

While the importing of electric vehicles is exempt from VAT and excise duties until 2022, as of 2015 both the first vehicle registration and environmental tax on emissions from cars have been abolished (Center for Environmental Initiatives, 2020; Ministry of Finance of Ukraine, 2018). In 2020, around 40% of motor vehicles registered in Ukraine were manufactured in 1999 or earlier and less than 1% of the vehicle fleet were electric or hybrid vehicles (Ministry of Energy and Environmental Protection Ukraine, 2021).

The Ministry of Energy and Environmental Protection expects that electric vehicles will make up only 3% of the domestic vehicle fleet in 2030 under current policies, which is in stark contrast to the initial target of a 50% share in 2030, set in the National Transport Strategy of Ukraine (Ministry of Energy and Environmental Protection Ukraine, 2021). Nevertheless, the electric car market is slowly growing and public charging points have increased by 57% in the period between 2019-2020 with a total of 8,500 charging points across the country (UkraineInvest, 2020).

In September 2020, the government extended the scope of the ‘Warm Loans Programme’ for energy efficiency improvements in buildings to include charging equipment for electric vehicles (Ministry of Energy and Environmental Protection Ukraine, 2020a).

Buildings

In 2018, buildings sector emissions accounted for approx. 8% of Ukraine’s total GHG emissions and the residential buildings sector alone was responsible for 30% of Ukraine’s total final electricity consumption (IEA,2020).

In January 2020, the cabinet of ministers approved a concept on energy efficiency in buildings and zero-energy consumption buildings along with a national action plan on these issues (Mitsovych et al., 2020). In 2020, a total of EUR 85m was spent on energy efficiency improvements in residential buildings through Ukraine’s National Energy Efficiency Fund (EUR 50m) and the ‘Warm Loans Programme’ (EUR 35m), which provides individual residents with loans for such improvements (Ministry of Energy and Environmental Protection Ukraine, 2021). In September 2020, the government prolonged the ‘Warm Loans Programme’ for another year and extended the scope to include the purchase of energy storage systems, charging equipment for electric vehicles and smart electricity meters (Ministry of Energy and Environmental Protection Ukraine, 2020a).

Despite these efforts, most residential and non-residential buildings are not yet up to date with modern energy efficiency standards: in Ukraine, energy needs for heating amounted to 250-450 kWh/m2 compared to 180 kWh/m2 in Germany or 150 kWh/m2 in Scandinavian countries (IEF, 2021).

The analytical review report for Ukraine’s NDC sets out four priority areas to cut emissions in the buildings sector: 1) nationwide modernisation of buildings, 2) replacement of low-efficiency boilers, 3) substitution of fossil-fired heating systems and 4) nationwide reconstruction of residential buildings (Ministry of Energy and Environmental Protection Ukraine, 2021).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter