Targets

Target overview

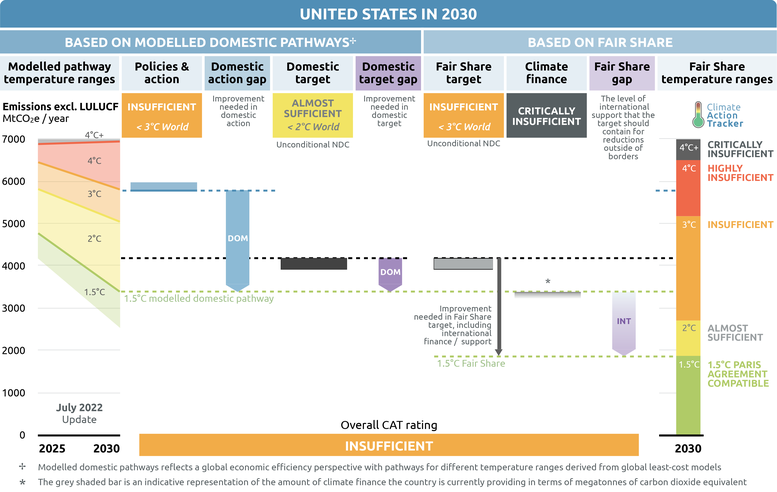

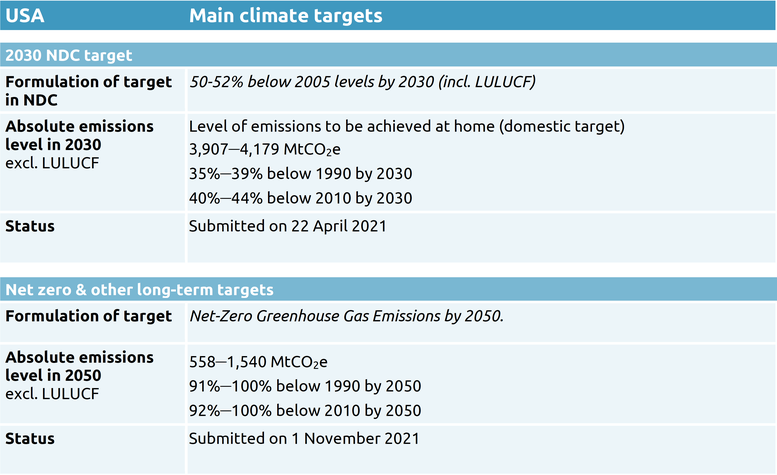

In its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), the US has set a target of reducing emissions by 50%–52% below 2005 levels by 2030 (U.S. Department of State, 2021a). This target covers all sectors and all greenhouse gases (GHG). The CAT excludes emissions from land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF) from this target, resulting in a 44%–47% reduction below 2005 levels by 2030. The CAT rates the US domestic target as “Almost sufficient” and its fair share target as “Insufficient”.

The US submitted a long-term strategy (LTS) to the UNFCCC in November 2021, officially committing to net zero emissions by 2050 at the latest (U.S. Department of State, 2021b).

The effects of COVID-19 induced a drop in emissions that helped the US to meet its 2020 targets under the Copenhagen Accord. Total emissions in 2020 decreased by 21% below 2005 as a result of the economic slowdown. The US 2020 target was to reduce emissions by 17% below 2005 levels by 2020 (U.S. Department of State, 2010). Despite reaching the 2020 target, GHG emissions bounced back in 2021 to pre-pandemic levels.

NDC Updates

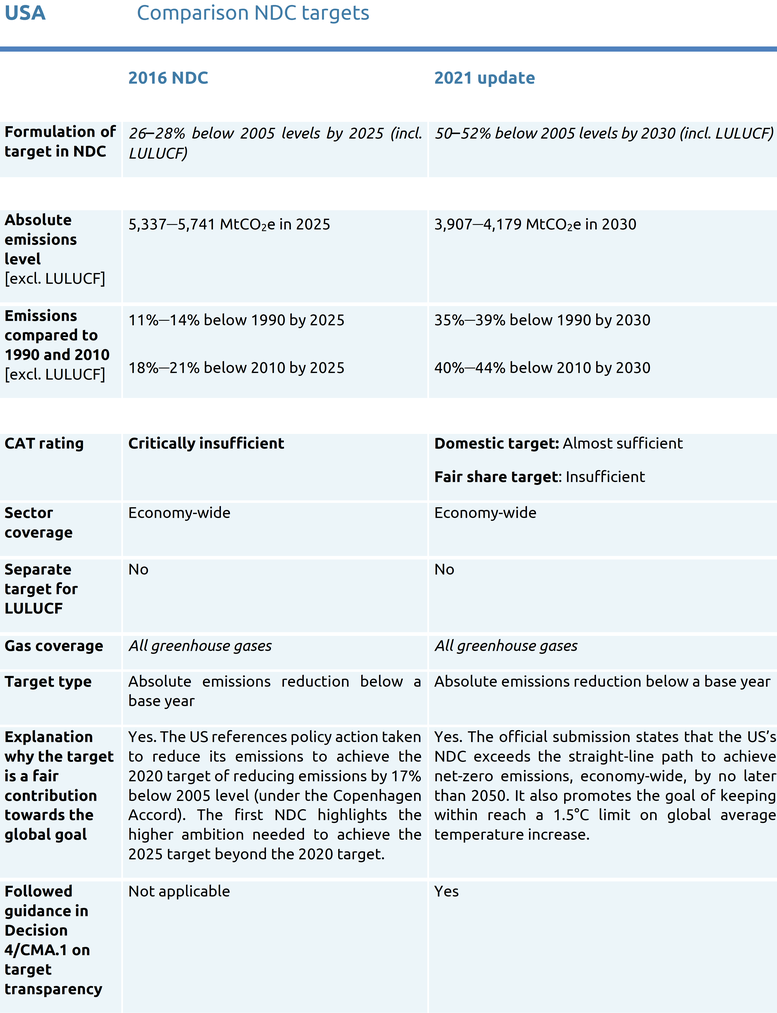

The US submitted a stronger target on 22 April 2021.

President Biden moved to re-join the Paris Agreement on his first day in office. In line with its re-joining, the US submitted a strengthened NDC, committing to reducing emissions by 50%–52% below 2005 levels by 2030, including LULUCF.

The CAT estimates that the 50%–52% reduction target in emissions including LULUCF would translate to a range of 3,907–4,179 MtCO2e absolute GHG emissions in 2030 excluding LULUCF (or 44%–47% below 2005 levels), depending on whether the sink from LULUCF is at the high or low end of the projections (U.S. Department of State, 2021a).

The new NDC target represents major progress beyond the Obama-era target of 26%–28% below 2005 levels by 2025, but is not quite enough to bring US domestic emissions in line with what would be needed to achieve the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C limit.

A CAT analysis indicates that the US should aim to reduce its national emissions by at least 57–63% below 2005 levels by 2030 (incl. LULUCF) and provide support to other countries in order to be consistent with the Paris Agreement 1.5°C limit and put the US on track to achieve President Biden’s stated 2050 net zero target (Climate Action Tracker, 2021d). Of all the NDC updates of the 2020/2021 round, the latest US target is the single biggest reduction in the global emissions gap (Climate Action Tracker, 2021a).

Note: Before September 2021, all CAT ratings were based exclusively on fair share

Target development timeline & previous CAT analysis

CAT rating of targets

The CAT rates NDC targets against what a country should be doing within its own borders as well as what a fair contribution to achieving the Paris Agreement’s long-term temperature goal would be. For what we call the ‘fair share target’, we consider both a country’s domestic emission reductions and any emissions it supports abroad through the use of market mechanisms or other ways of support, as relevant.

The US does not intend to use market mechanisms and will achieve its NDC target through to domestic action alone. We rate its NDC target against both domestic and fairness metrics.

We rate the target of reducing emissions by 50%–52% (or 44%–47% excluding emissions from land-use, land-use change and forestry) below 2005 levels by 2030 as “Almost sufficient” when compared to modelled domestic emissions pathways. The “Almost sufficient” rating indicates that the US target in 2030 is not yet consistent with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C temperature limit but could be, with moderate improvements. If all countries were to follow the US approach, warming could be held at—but not well below—2°C. Although the proposed target represents a significant improvement compared to its first NDC, the new US target is not stringent enough to limit warming to 1.5°C, and needs further improvements.

We rate the target of reducing emissions by 50%–52% (or 44%–47% excluding emissions from land-use, land-use change and forestry) below 2005 levels by 2030 as “Insufficient” when compared with its fair-share emissions allocation. The “Insufficient” rating indicates that the US fair share target in 2030 needs substantial improvements to be consistent with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C temperature limit. Some of these improvements should be made to the domestic emissions target itself, others could come in the form of additional financial support for emissions reductions achieved in developing countries. If all countries were to follow the US approach, warming would reach up to 3°C.

The US’ international climate finance is rated “Critically insufficient” (see below) and is not enough to improve the US’s fair share rating.

We rate the US international public climate finance contributions as “Critically insufficient.” The US has committed to increase its climate finance, but contributions to date have been very low compared to its fair share. To improve its rating the US needs to ramp up the level of its international climate finance contributions in the period post-2020 and accelerate the phase-out of all fossil finance abroad (not only coal).

A high share of existing US contributions has climate as a main component and is largely based on grants, which are more concessional than loans. The US climate finance contributions also exhibit, on average, a declining trend over recent years up to 2019 (OECD, 2018). A clear and sustained increase in international finance contributions is fundamental in the period post-2020.

The Biden Administration announced its International Climate Finance Plan the same day the US submitted its new NDC. The plan focuses on the role of the US to scale up and mobilise international climate finance and align it with country needs, strategies, and priorities to help unlock deep GHG emissions reductions in developing countries. Notably, the plan also calls for a phase-out of international finance for “carbon intensive fossil fuel-based energy” both bilaterally and through multinational fora (The White House, 2021e).

The plan aims to provide the US government with a strategic vision on international climate finance with a 2025 horizon and outlines instruments to globally mobilise USD 100bn a year for developing countries from public and private sources. The plan directs US departments, agencies, and development partners to define a climate change strategy and incorporate climate considerations into their international work and investments. The US also intends to ensure that future reporting is transparent and aligned with the strategic approach to climate finance (detailed reporting, tracking finance and enhanced reporting on mobilisation and impact).

In September 2021, at the United Nations General Assembly, President Biden committed to quadruple annual public climate finance overseas to USD 11.4bn a year by 2024 (relative to the average level during President Obama’s term). This announcement builds on the April 2021 commitment to double annual public climate finance overseas by 2024 (UK Government and UNFCCC, 2021).

In March 2022, the US Congress approved USD 1bn on international climate finance. This finance provision, which is slightly higher than the spending under the Trump administration (Donor Tracker, 2021), falls far short of Presidents Biden’s USD 11.4bn/year pledge the year before. The bill includes USD 270m for adaptation finance, more than ten times lower than President Biden’s pledge of USD 3bn for adaptation finance by 2024. Notably, the bill does not include any funding for the Green Climate Fund (GCF), the primary international vehicle for supporting developing countries in their efforts to respond to and build resilience to the climate crisis (DeLauro, 2022).

Aligned with his commitments, President Biden requested more than USD 11bn for international climate finance in the budget plan of 2023. This marks a significant increase from the USD 2.7bn requested for 2022, of which USD 1bn was approved. The proposal includes approximately USD 1.6bn to the GCF (The White House, 2022f). However, the budget plan represents an initial proposal that is expected to be scaled back in negotiations with Congress before it gets enacted.

The commitment of USD 11.4bn a year by 2024 falls short of the US’ fair contribution and is not enough to close the gap to mobilise international climate finance towards the USD 100bn goal per year, let alone the USD 1bn approved by the congress for 2022. The US would need to substantially scale up its international climate finance provisions in the following years to meet the climate finance targets and regain its credibility as world climate leader.

The USD 100bn global goal is insufficient post-2020. This level of finance, if achieved by a sustained upwards trend in annual contributions, would improve the CAT finance rating. After the June 2021 G7 Summit, President Biden committed up to USD 2bn climate finance “to support developing countries as they transition away from unabated coal-fired power” (Piper, 2021). No clarification on how this amount relates to previous announcements was provided.

In early 2021 the US announced its intention to end overseas funding of “high emitting” fossil fuel projects, but without specifying what is considered ‘high emitting’ (Rowling, 2021). No plans beyond this initial announcement have yet been legislated. President Biden vowed to scale back and end public investments in carbon-intensive fossil fuel-based energy overseas, although he did not provide a date nor further details (The White House, 2021e). The G7 countries collectively committed to end “new direct government support for unabated international thermal coal power generation by the end of 2021” (G7 United Kingdom, 2021). However, there is currently no evidence that US support has stopped for on-going fossil fuel projects abroad, such as the Jawa 9-10 Suralaya Coal Plant in Banten in Indonesia and the Long Phu 1 Coal Plant in Vietnam (EndCoal, 2020).

The announcements made by the Biden Administration are a good sign that the US trend in climate finance is changing, but the Administration and the US Congress have yet to turn them into actions. The critically insufficient rating reflects past action, and the US can improve its rating if the new administration implements and improves its announcements.

Net zero and other long-term target(s)

The Biden administration submitted an updated long-term strategy to the UNFCCC in November 2021, officially committing the US to net zero emissions by 2050 at the latest. The net zero target covers all greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, makes transparent assumptions on CO2 removal by nature-based and technology-based solutions, and specifies several key components for comprehensive planning (U.S. Department of State, 2021b).

The US government has several avenues to improve the scope, target architecture and transparency of its net zero target. The US government could include international aviation and shipping in its target coverage, and explicitly commit to reach net zero emissions within its own borders without any use of international offsets. Furthermore, the target itself could be enshrined in law in combination with adopting a legally-binding review, revision, and reporting mechanism. The US government should further explain why its net zero target is a fair contribution to the global goal of limiting warming to 1.5˚C above pre-industrial levels, and transparently address any existing gap between its net zero target and what would be a fair target.

For the full analysis click here.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter