Country summary

Overview

Viet Nam lacks policy action for a green economic recovery, and has not focused efforts on emissions reductions. Viet Nam has recent positive renewable energy policy developments, but this does not outweigh carbon intensive plans. Solar capacity has increased despite the pandemic and global supply chain disruptions, and Viet Nam has met its solar target early. Viet Nam could become a regional leader for solar and has a large untapped potential for offshore wind, yet the coal pipeline is still expansive even considering draft plans to cancel some planned coal projects.

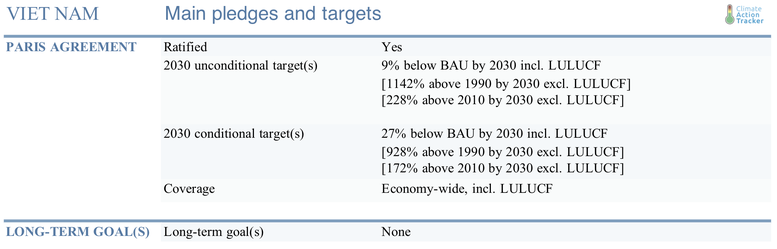

Viet Nam updated its Paris Agreement NDC target in 2020 without driving more ambitious action. The update resulted in a slightly lower emissions level that is still well above the current policy projection. The CAT continues to rate the target as “Critically insufficient”. A target based on a reduction from current policy projections would ensure real progress in climate action.

We expect that GHG emissions in 2020 will be 0-4% lower than 2019 levels. Despite the pandemic, the majority of GDP projections indicate economic growth for 2020 and beyond, although they are significantly lower growth rates than the pre-pandemic projections. Viet Nam’s renewable energy projects have pressed ahead in 2020, including the largest solar farm in Southeast Asia. Viet Nam has not initiated a green recovery. Economic stimulus funds, worth over USD 13 billion, have so far focused on tax breaks, debt restrictions and preferential interest rates.

Renewable energy can help revive the economy with job creation opportunities, if the stimulus were directed appropriately. Over the past three years, the nation has added 4.5 GW of solar, and met its 2025 solar target in 2019. The new solar auctions plans are a recent positive policy development. Viet Nam needs to address the required electricity grid upgrades, as renewables are being curtailed, placing mounting risks on the bankability of renewable projects. Renewables have reached the tipping point as the lowest cost option to meet the country’s growing electricity demand while supporting sustainable development.

If it were to abandon a larger portion of its plans for substantial added coal-fired power generation in favour of a shift to renewable energy, Viet Nam could become a leader in South East Asia. Viet Nam has set a new renewable energy target of 15-20% by 2030 and 25-30% by 2045 in the total primary energy supply but still has the second largest coal pipeline in Southeast Asia. The draft Power Development Plan 8 indicates some of the planned coal capacity will be cancelled or postponed. Viet Nam’s intends to ramp up gas imports and gas-fired power capacity, despite uncertainties arising from the pandemic’s impact on the global market, and trends towards decarbonisation with renewables. These plans will likely result in stranded assets given the need for the global phase-out of coal by 2040, including in Viet Nam and to reach more than 50% share decarbonisation in electricity generation by 2030 in the ASEAN region.

The CAT’s emissions projections for 2030 for Viet Nam are between -4% and 6% different to the pre-COVID-19 current policy projection. The CAT’s projections are presented as a range to account for the uncertainty of the pandemic’s impact on Viet Nam’s economic growth. In any case, emissions will increase sharply by 2030 with no sign of peaking. The extent of the emissions increase will depend on a number of factors including the direction of Viet Nam’s policy response to COVID-19 considering the substantial funds made available, while the CAT’s projections are based on a range of GDP projections assuming the same emissions intensity. If Viet Nam’s policy response is fossil fuel heavy, emissions are likely to be high in 2030.

The CAT’s rating for Viet Nam remains unchanged as ‘Critically Insufficient’. The updated Paris Agreement target is 17 MtCO2e stronger and the transparency and sectoral coverage has improved, yet the target does not drive real climate action as it can still be easily met with current policies. Viet Nam’s 2030 climate commitment is consistent with a warming of over 4°C: if all countries were to follow Viet Nam’s approach, warming would exceed 4°C. This means Viet Nam’s climate commitment is not in line with any interpretation of a “fair” approach to the former 2°C goal, let alone the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C limit.

According to our analysis, Viet Nam will vastly overachieve its updated NDC targets with currently implemented policies. The new targets are based on a new but still hyperinflated business-as-usual scenario. A target based on a reduction from current policy projections would ensure real progress in climate action.

Viet Nam’s COVID-19 response involves a USD 1.16 billion assistance package for company tax breaks or tax extensions, plus a credit support and fiscal package of USD 12 billion to restrict debt and set preferential interest rates, with other details to be confirmed. To date, Viet Nam instituted a temporary, 22 day lockdown period, and has one of the world’s lowest rates of COVID-19 transmission. The short lockdown and very low transmission rates may allow for the economy to continue growth, albeit at a lower level than 2019. Most GDP projections for 2020 show economic growth. Projections ranging from -1% decline to 4.2% growth for 2020. Projections also show the possibility for an economic rebound of up to 6.7% growth by 2021.

Viet Nam has introduced solar policy developments and overachieved national solar targets. The solar feed-in-tariff expired in June 2019, followed by a 10 month period without a replacement policy. The government extended the tariff in 2020, with a plan to transition the feed-in-tariff to competitive bidding through a solar auction strategy by the end of 2020. The pilot program will begin the transition, and is expected to run in November 2020 to May 2021.

There are 29 solar projects with a capacity of 1.6 GW that are likely to be approved for the pilot transition programme, with the possibility of another 103 solar projects with an additional 10 GW capacity. The largest solar farm in Southeast Asia entered into operation in Viet Nam in October 2020, despite the pandemic and global supply chain disruptions, with a generation capacity of 0.42 GW. In less than two years, Viet Nam went from negligible installed capacity in 2017 to 4.5 GW installed in 2019, overachieving the revised PDP solar targets over five years early. The revised PDP 7 aimed for 850 MW of solar in 2020 and 4 GW by 2025.

Viet Nam is currently revising its planned coal power generation capacity, and while some coal plans may be cancelled or postponed, the coal pipeline remains substantial. The current power development plan (revised PDP7) is coal heavy to cope with rising energy demand.

Despite plans to cancel some coal projects, Viet Nam still plans to considerably ramp up coal. The government’s draft power plan PDP 8 cancels or postpones more than 17 GW of planned coal in the revised PDP 7. Around 18 GW is still planned for development in the 2020 to 2025 period, with 7.6 GW planned for post 2030. Viet Nam has a capacity of 20 GW of coal.

The current policy pathway is not in line with the Paris Agreement, given the need to phase out coal for power generation by 2040 and to reach a Paris Agreement-compatible share of decarbonised electricity generation of at least 50% by 2030 in the ASEAN region according to research by Climate Analytics.

There is increasing resistance to coal within Viet Nam. Six provinces out of 63 have called for the cancellation of planned coal power plants due to environmental concerns. The proposed cancellations in the draft PDP 8 amount to over 17 GW of coal-fired capacity. The Viet Nam Business Forum has cited concerns over the financial, security, environmental and public health risks of coal, and has developed a business case for investment in clean energy, rather than coal.

The revised PDP 7, the draft PDP 8 and Resolution 55 have shown an increasing policy commitment to gas. The global market for gas is uncertain, especially in light of the global market disruption related to the pandemic. Uncertainty in the sector risks investment in stranded assets, when the transition can focus on long term decarbonisation with renewables.

The large uptake of renewables has created pressure on the electricity grid. The state-owned company Vietnam Electricity (known as EVN) has curtailed renewable energy without compensation, placing mounting risks on the bankability of renewable projects. Between June 2019 and January 2020, 0.44 GW of new wind and solar were forced by the EVN to curtail output to the grid.

A draft law under consideration by the National Assembly, if passed, would create a national plan to reduce GHG emissions, including strategies for ministries. The draft also includes plans for Viet Nam to join international carbon markets.

Viet Nam’s climate policy is particularly important given its vulnerability to climate change. Climate policy can help achieve sustainable development and address energy security issues, particularly through transitioning to renewable energy to meet the domestic energy demand and support job creation.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter