Summary

Overview

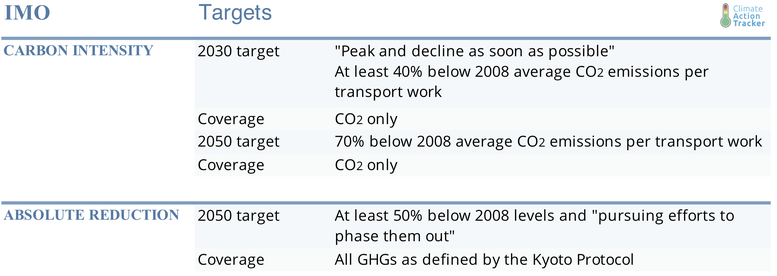

The IMO continues to move at a snail’s pace, failing at its recent meetings to adopt meaningful measures to cut international shipping emissions. The sector’s emissions will continue to grow through to 2050 unless there is further policy action. The CAT rates the 2030 target as highly insufficient (changed from critically insufficient in our previous assessment), a change in rating that is not derived from any improvement in action, but rather from an IMO decision on the exact definition of the target. The sector will not meet this already weak target with its current measures and would need to vastly exceed the target to get itself on a Paris compatible pathway.

The IMO may be forced to accelerate its pace with the recent release of the ‘Fit for 55’ package under the European Green Deal. Four proposed regulations are addressing either maritime emissions or facilities available at ports to facilitate the use of low or zero-carbon fuels. The revised EU ETS includes international maritime emissions covering half of both incoming and outgoing voyages, ships at berth and intra-EU voyages.

The scheme will not allow any free emissions allowances and thus will impose a real cost on ship owners. However, its full implementation will not take place before 2026 when 100% of emissions will be covered, starting with only 20% in 2023. The proposed FuelEU Maritime regulation sets a binding emissions intensity reduction target per energy consumption of 6% by 2035 and 75% by 2050 below 2020 levels. The revised directive on fuel taxation newly includes navigation and covers intra-EU navigation, fishing and freight transport incentivising the use of zero or low carbon fuels. By 2030, if proposed revisions are passed under the Alternative Fuel Infrastructure Directive, ports will need to provide shore-side power outputs to meet 90% of the demand however. Worryingly, the regulation also incentivises the development of natural gas infrastructure at ports and leaves it to member states to decide on the level of deployment by 2025, which creates a material risk of getting stuck with high-cost, high emission stranded assets.

Updated historical data from the IMO shows some concerning trends. Methane emissions increased by 150% between 2012 - 2018, mostly driven by an increase in ships equipped with Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) fuelled engines. LNG is not an option to support the transition to alternative energy sources, notwithstanding a perception in the industry that it is a key bridging fuel. Studies have shown that instead of reducing emissions, adopting LNG could increase international shipping’s climate impact when the whole life cycle of all GHG gases are taken into account. Investments in LNG facilities are growing and could lead to stranded assets or perpetuate a carbon “lock-in” effect as ships and onshore LNG infrastructure would make it more difficult to transition to low-carbon fuel.

In its latest GHG study, the IMO changed its approach to estimating emissions. Historically, it has calculated emissions using a method that allocated emissions based on the type of vessels. As this led to an overestimation of the international shipping emissions, the IMO has now introduced a method based on the voyage taken, in line with IPCC guidelines, defining international voyage between two ports of different countries. Under the new method, historical annual emissions in the years 2010-2020 are almost 200 MtCO2 per year lower than under the vessel-based method (between 142 MtCO2e and 183 MtCO2 difference per year). While this new approach represents a step in the right direction to ensure consistency across IMO reporting and country GHG inventories following IPCC guidelines, it is key to ensure that a uniform approach is taken to avoid double counting or loopholes in emissions accounting. The IMO 4th GHG study invites its member to reconsider the targets baseline based on this new approach which would lead to a more ambitious GHG 2050 target.

Policy action has been far too slow. At its November 2020 meeting, the IMO failed to pass meaningful short-term policies measures that were on the table. To reduce emissions, the IMO member states have voted for draft energy efficiency requirements for existing ships. They discussed two indexes for adoption in June 2021 – the EEXI and the CII – to provide shipowners with a cap in improving their energy efficiency. However, they set the bar low enough that ships will already comply with the new requirements due to their slow steaming. How carbon intensity is defined has also yet to be decided, with two options on the table: a supply-based metric (AER) and a demand-based metric (EEOI). The ICCT estimates that the AER would allow an actual level of emissions by 2030 lower than the EEOI, although both remain far from what a Paris compatible pathway would require and still allow emissions to grow.

The IMO did no better at its June 2021 meeting. The Marine and Environmental Protection Committee (MEPC) agreed on the pace it would reduce its CO2 emissions to meet its already weak –and close to being achieved –“2030 carbon intensity target. While still meeting its 2030 target, this 2% annual carbon intensity reduction between 2019 - 2030 will allow emissions to grow in the current decade instead of peaking as required by the IMO’s own strategy to peak GHG emissions as soon as possible” and by Paris compatible pathways.

The Republic of the Marshall Islands and the Solomon Islands governments have called for a carbon levy on shipping emissions – starting at USD 100/tCO2, then transitioning to USD 250/tCO2. While the starting price would be too low to have any impact on reducing emissions, USD 250/tCO2 would allow zero-emissions technologies to become competitive and could potentially lead to full decarbonisation of the sector by 2035. The outcome of the June 2021 meeting is going in the opposite direction: no decision was reached on whether to implement the carbon tax. The committee decided on its usual very slow pace to reach a decision: the proposal will be discussed over the course of the next two years for implementation – if any – in the following years.

We now rate the 2030 carbon intensity target as ‘highly insufficient’, compared to ‘critically insufficient’ in our 2020 assessment. This change is the result of the MEPC’s decision in June 2021 to annually reduce carbon intensity by 2% and updated current policies projections from the 4th IMO GHG study. See the assumption section.

Whereas the Kyoto Protocol explicitly made the IMO responsible for reducing international shipping emissions, the Paris Agreement calls for economy-wide reductions and does not mention the IMO. In the absence of leadership from the IMO, some countries have started to take action to reduce international shipping emissions on their own. For example, the UK included international shipping emissions in its sixth carbon budget (2033-2037), which is set to reduce GHG emissions by 78% below 1990 levels.

To keep the Paris Agreement temperature goal within reach, it is imperative that national governments take responsibility for emissions from international bunkers, and actively work to bring those to zero. The CAT analysis of international shipping coverage in countries’ NDCs is here: CAT_2021_06_InternationalShipping_NDCTracking and our evaluation of its inclusion in net zero targets will be available on our individual country pages later in 2021.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter