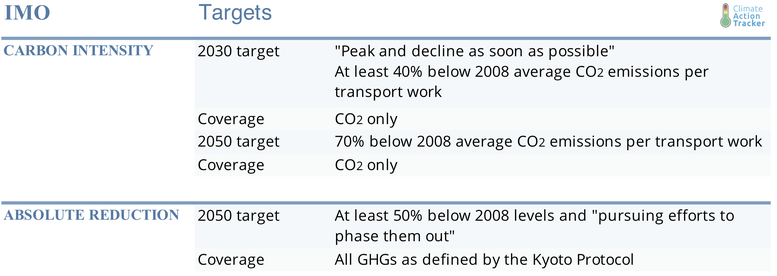

Targets

Summary table

In April 2018, the IMO adopted its Initial Strategy to reduce GHG emissions (IMO, 2018). The strategy recognises the need for emissions to “peak and decline” and to pursue “efforts towards phasing them out as called for in the Vision as a point on a pathway of CO2 emissions reduction consistent with the Paris Agreement temperature goals”. It includes one target for 2030 and two targets for 2050, both compared to the 2008 baseline.

In 2008, the year that the IMO takes as a baseline for its targets, average ship speed and corresponding emissions were at an all-time high (ships are less efficient at faster speeds). In a response to falling demand following the 2008 financial crisis, carriers reduced supply capacity by scrapping older vessels, cancelling orders for new ships and lowering ship speeds, to avoid freights rates reduction; all measures which drove emissions reductions (Spero & Raval, 2013).

Methodological considerations: Voyage vs Vessel based approaches

In its 4th GHG Study, the IMO presents two methodological approaches to reporting historical emissions: one based on the type of vessel and the other based on the voyage of the ship. The report puts forward three key arguments in favour of using the new voyage-based approach and invites the IMO members to reconsider the targets’ base year: the voyage-based approach is aligned with IPCC guidelines; it is closer to top-down estimates such as the IEA data and the vessel-based approach have overestimated international shipping emissions allocating emissions by type of ships which could have had also domestic travels. While this new approach represents a step in the right direction to ensure consistency across IMO reporting and country GHG inventories following IPCC guidelines, it is key to ensure that a uniform approach is taken to avoid double counting or loopholes in emissions accounting (Psaraftis & Kontovas, 2021). In this assessment, we have used the voyage-based historical emissions to ensure consistency with our country analysis, which reports GHG emissions following IPCC guidelines. Historically, the IMO has used the vessel-based approach and it remains unclear if the IMO will fully transition to the new methodology and update its targets using the new estimates - or if the organisation will keep the baseline as evaluated in its 3rd IMO GHG study. In any event, it should be emphasised that there remains significant, if not substantial, uncertainties in relation to international shipping greenhouse gas emissions.

2030 target

Under the Initial Strategy, IMO member countries agreed to cut carbon intensity of the fleet by at least 40% below 2008 levels by 2030. In its June 2021 meeting (the 76th Marine Environment Protection Committee), the IMO was set to decide on how to define ‘carbon intensity’. Two options were on the table:

- Demand based: the amount of CO2 emitted per each tonne of goods per nautical mile (gCO2/t-nm) - also called Energy Efficiency Operational Indicator (EEOI).

- Supply based: the amount of CO2 per capacity of carriage (deadweight) per nautical mile (gCO2/dwt-nm) or also called Annual Efficiency Ratio (AER).

The ICCT estimates that the supply-based approach (i.e. AER) would result in fewer actual emissions by 2030 than the EEOI. Additionally, the IMO’s reporting system provides the necessary data to apply the supply-based approach, whereas it would take years to implement the EEOI, as it would have to first implement a reporting framework to gather the necessary data (ICCT, 2021). The outcome of the MEPC76 indicates that the IMO will choose a 2% yearly carbon intensity reduction between 2019 - 2039, which would result in emissions reduction levels aligned with the supply-based approach (AER).

However, IMO member countries are likely to miss their 2030 carbon intensity target. Using the AER metric, we estimate that CO2 emissions would lead to approximately 750-784 MtCO2 in 2030, depending on the growth in trade, representing an increase of 10-12% below projected emissions levels by 2030 under current policies. This target is not ambitious: the sector had already reached more than a 30% reduction in carbon intensity in 2018 (Comer et al., 2018; A. D. (ICCT) Rutherford et al., 2020). Industry players and think tanks have called for stronger targets to be included in the revised 2023 strategy (Climate Home News, 2020; Ship & Bunker, 2020).

2050 target

The Initial Strategy also sets a carbon intensity target of 70% below 2008 levels by 2050. Using an AER metric, we calculate that this corresponds to an absolute CO2 emission reduction of 498-568 MtCO2 in 2050 compared to 2008, or 18-29%. Under our current policy projection (973-1086 MtCO2e in 2050), the shipping sector is not on track to reach this 2050 target.

The Strategy includes a second 2050 target, which covers all GHG emissions. Under this goal, all international shipping GHG emissions would be cut by at least 50% below 2008 levels. Achieving this target would result in an estimated absolute GHG emission level of 397-501 MtCO2e in 2050. For CO2 emissions, the level would be 388-491 MtCO2. It is the CO2 amount that is displayed in our graph, as our rating system is based on CO2 emissions only. The range of the target represents the uncertainty due to the choice of methodological approach to measure historical emissions: voyage-based and vessel-based (lower and higher bounds respectively). Furthermore, when considering GHG emissions in total, the target is likely to be impacted by the shift already observable from CO2 emissions to methane emissions through ships transitioning to LNG as a fuel instead of heavy fuel oil (HFO).

While the absolute target is stronger than the carbon intensity target, there is room for further strengthening, particularly in light of the fact that according to its strategy, the IMO also aims to go about “pursuing efforts towards phasing [emissions] out as called for in the Vision as a point on a pathway of CO2 emissions reduction consistent with the Paris Agreement temperature goals” (IMO, 2018). The difference between the carbon intensity target and the absolute target indicates the role of trade growth in emissions and the importance of setting an absolute target independently of economic forecasts. Studies show that cost-effective, full decarbonisation of the sector is possible before 2050 (Energy Transitions Commission, 2019; OECD, 2018).

Country targets: NDCs & net zero

To keep the Paris Agreement temperature goal within reach, it is imperative that national governments take responsibility for emissions from international bunkers, and actively work to bring those to zero.

For countries that the CAT analyses, we will also begin to track whether international shipping has been included in their net zero targets. This information will be available on individual country pages in the coming months.

Rating

The CAT rates the 2030 and 2050 carbon intensity targets as ‘highly insufficient’, indicating that the target is consistent with limiting warming to between 3°C and 4°C if all other sectors were to follow the same approach as international shipping. It is important to note that the 2030 carbon intensity target is highly dependent on projected demand. Our target calculations are based on demand projections as provided by the IMO 4th GHG study. See assumptions sections for more details.

The CAT rates the IMO’s 2050 second target, assessed here on CO2 emissions only, as ‘insufficient’, indicating that the target is consistent with limiting warming to between 2°C and 3°C if all other sectors were to follow the same approach as international shipping.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter