Policies & action

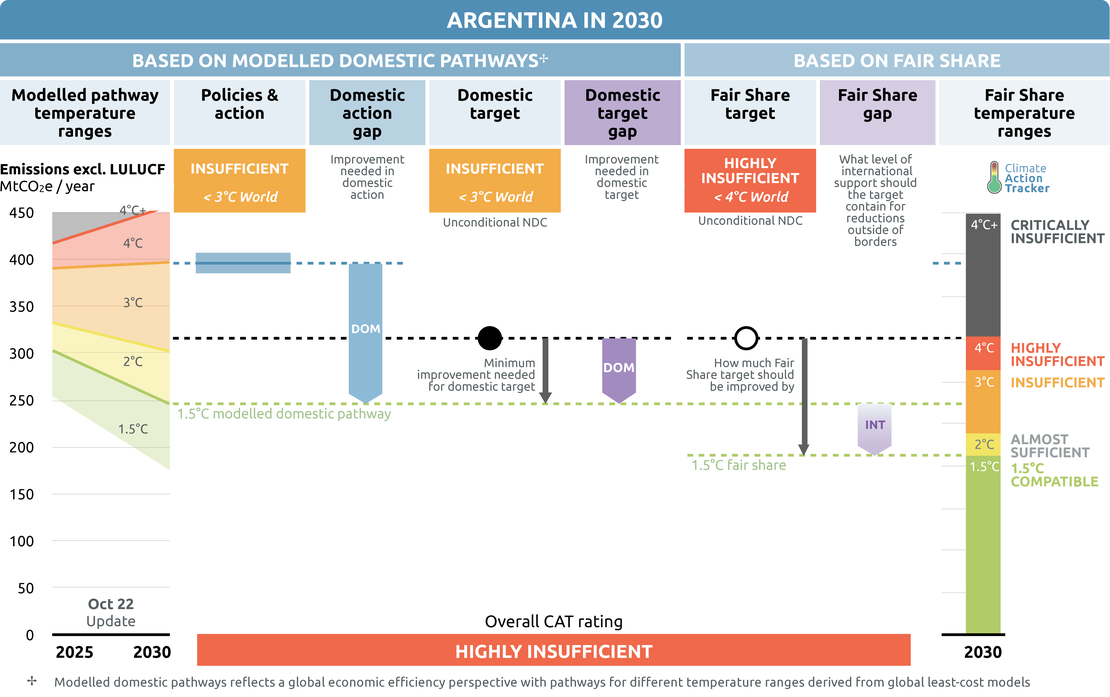

We rate Argentina’s policies and actions as “Insufficient” when compared with modelled domestic emissions pathways. The “Insufficient” rating indicates that Argentina’s climate policies and action in 2030 need substantial improvements to be consistent with the 1.5°C temperature limit. If all countries were to follow Argentina’s approach, warming would reach over 2°C and up to 3°C.

Argentina’s current policies would lead to above 3°C when compared to its fair share contribution. Whether Argentina will achieve its unconditional NDC depends mostly on how it develops its energy sector. The sector’s development will be directly affected by the economic recovery after the current crisis, the expansion of fossil fuel infrastructure and renewables, and future energy demand.

Argentina’s policies and action rating has improved compared to CAT’s last assessment. This change is not due to more ambitious policies being implemented, but rather to revised GDP growth forecasts for the country, reflecting both the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, and Argentina’s ongoing economic crisis, which lead to a lower emissions increase.

In 2021, emissions in Argentina rebounded back to 2019 levels after a sharp drop in 2020 due to COVID-19. This puts Argentina’s projections under current policies at approximately 21-28% above its 2030 target. Under the planned policies scenario, if Argentina were to implement additional policies to scale-up low carbon energy sources and reduce energy demand, it could reduce that gap to 9%–15% above its unconditional target of 315.9 MtCO2e by 2030 (excl. LULUCF, in AR4 GWP). To be consistent with the 1.5°C temperature limit, Argentina would need to develop substantially more ambitious policies, especially to develop renewable energy, stop deforestation, and reduce livestock-related emissions.

Since taking office in December 2019, the current government undertook a series of changes in the structure of its ministries. On the one hand, the Secretariat of Energy dismantled the Sub-Secretariat of Renewables and the former Sub-Secretariat of Hydrocarbons was upgraded to a secretariat, indicating the government’s priority in oil and gas exploitation over the development of renewables in the energy sector. On the other hand, both the former Secretariat of Agriculture and Secretariat of Environment took up ministerial ranks again, with a Secretariat of Climate Change under the environment ministry (Gobierno de Argentina, 2019).

This administrative restructuring has resulted in an increased focus on developing fossil fuel infrastructure and nuclear power, and a deprioritisation of renewables. For example, the design and timeline of the next renewable auction round, RenovAr 4 (Djunisic, 2019), has not been defined as of September 2022 and seems to be a low priority for the new government.

In 2022, the government fast-tracked a previously mothballed project to build a pipeline connecting Vaca Muerta with the national gas network to enable a substantial ramp-up of production. The first stage of the project is expected to be completed during 2023, with an additional pipeline planned for 2024.

Additionally, new conventional oil field discoveries off the coast of Namibia have sparked exploration plans off the coast of Buenos Aires. This is because both continents were much closer at the time of the formation of those reserves. The first explorations will be led by YPF with Shell and Equinor and will start in 2023. They expect to find up to 1 billion oil barrels (Government of Argentina, 2022c).

In July 2022, the government agreed to implement a segmented tariff scheme to make subsidies less regressive, and possibly save up to USD 500min subsidy spending in 2023. The new finance minister, Sergio Massa, announced shortly after his appointment that the subsidy scheme would further include a consumption cap of 400 kWh per household per month, beyond which all subsidies would be removed (Diamante, 2022). This is a step in the right direction, but in the context of high political instability, and substantial internal pushback on these reforms, their implementation and future impact are still unclear.

In 2021, the government updated its biofuel blending mandates, reducing biodiesel blending from 10% to 5%, with the option of a further reduction to 3% depending on how input prices after final fuel prices for consumers. A recent study has calculated that this reduction can lead to increasing cumulative emissions by 7.9–11.7 MtCO2e in the period 2021–2030 (Magnasco & Caratori, 2021).

Policy overview

Most recent estimates show that the ongoing domestic crisis and the effects of the global economic fallout as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine led to a decrease in Argentina’s GDP by 9.9% 2020, followed by a recovery of 10.3% in 2021(Banco Central de la República de Argentina, 2022; IMF, 2022; OECD, 2022). The CAT estimates that this economic slowdown decreased economy-wide emissions by 6.2% in 2020 compared to 2019 levels and increased again by 6% in 2021 (excl. LULUCF).

Under current policies, total emissions (excluding LULUCF) are still projected to grow significantly after 2021, namely by about 20%–27% above 2010 levels by 2030, reaching about 384–407 MtCO2 in 2030 (excl. LULUCF). This is equivalent to emissions 63%–72% higher than 1990 levels and means missing the unconditional NDC target by 21%–28%. Argentina’s policies and action rating has improved compared to CAT’s last assessment. This change is not due to more ambitious policies being implemented, but rather due to revised GDP growth forecasts for the country, reflecting both the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, and Argentina’s ongoing economic crisis, which lead to a lower emissions increase.

Our analysis of current policies is based on the projections developed by National University of Central Buenos Aires (UNICEN) (Keesler et al., 2019). The planned policy scenarios are also based on a set of UNICEN scenarios that assume full implementation of the renewable targets, additional energy efficiency measures and other mitigation measures from sectoral plans. These scenarios are aligned with the assumptions and developments included in the Energy Scenarios of 2019 from the Ministry of Energy (Ministry of Energy and Mining Argentina, 2018).

Even assuming full implementation of current and planned policies, Argentina will not be able to achieve its unconditional NDC target. Additionally, current and future plans for the development and exploitation of national oil and natural gas resources can threaten the achievement of Argentina’s targets (see more detail in the section on energy supply below).

In January 2018, Argentina implemented a carbon tax covering most liquid and solid fuels sold in the country, originally based on a price of 10 USD/tCO2e, which was then scaled down to 5 USD/tCO2e. In January 2019, the tax also became operational for fuel oil, mineral coal, and petroleum coke, at 10% of the full tax rate, with an annual increase of 10 percentage points until reaching 100% in 2028. The tax is estimated to cover 20% of the country’s GHG emissions. Natural gas is exempted from the tax, as is CNG and fuel consumption in international aviation and shipping, as well as the export of these fuels.

The tax is a first step in the right direction. Yet, significantly higher carbon prices are required for Paris compatibility (at least USD 40–80/tCO2 by 2020 and USD 50–100/tCO2 by 2030 (Stiglitz et al., 2017)). Our policy projections, as well as the new scenarios from the Ministry of Energy, do not yet specifically reflect the recently implemented carbon tax. An earlier proposal in Argentina included a carbon price of 25 USD/tCO2e but the final decision was made for a much weaker tax.

National NGOs have criticised the final rule as too unambitious and merely a tool to align with international activities to increase the chances for access to the OECD, rather than an instrument to safeguard the environment (FARN, 2017). The law distributes the tax revenues to different areas, most of which are not directly linked to climate change or environmental issues (Ley 27430 - Impuesto a Las Ganancias - Modificación, 2017).

In July 2019, Argentina was the first country in Latin America to declare a climate emergency. While the draft declaration included 15 points and an action plan, the final text was reduced to only two paragraphs and is considered to have symbolic character. The declaration was approved after passing through the Senate (Himitian, 2019).

Since taking office in December 2019, the current government has undertaken a series of changes in the structure of ministries to decrease government spending and set priorities in line with its agenda (Government of Argentina, 2019). The following departments dealing with climate change were directly affected by these changes: both the former Secretariat of Agriculture and Secretariat of the Environment took up ministerial ranks again, with a dedicated Secretariat of Climate Change under the new Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development.

The Secretariat of Energy further dismantled the Sub-Secretariat of Renewable Energy, merging it into a broader Power Energy Sub-Secretariat. The former Sub-Secretariat of Hydrocarbons was upgraded to a secretariat, a clear indication of the government’s priority on oil and gas exploitation over renewables development in the energy sector. This administrative restructuring has resulted in an increased focus on developing fossil fuel infrastructure and nuclear power, and a deprioritisation of renewables.

In December 2019, the Congress passed a law on climate change (ley n.° 27520) that seeks to establish minimum budgets for the adequate management of climate change, including for the design and implementation of mitigation and adaptation policies, actions, instruments, and strategies. The law makes provisions, amongst others, for the development of a National Climate Change Response Adaptation and Mitigation Plan (PNAyMCC), the Jurisdictional Response Plan, a National System for GHG Inventory and Monitoring of Mitigation, and institutionalises the National Climate Change Cabinet (GNCC) (National Congress of Argentina, 2019a). The law positions the treatment of climate change as national policy and leaves an institutional legacy ensuring the permanence in time of the National Climate Change Cabinet, even after the change in government.

As of September 2022, the government is still working on its new National Climate Change Response Adaptation and Mitigation Plan, as well as on its Long-term Strategy. It is uncertain to what extent sectoral mitigation plans designed during the previous administration are still being implemented and/or will be incorporated into the forthcoming plan.

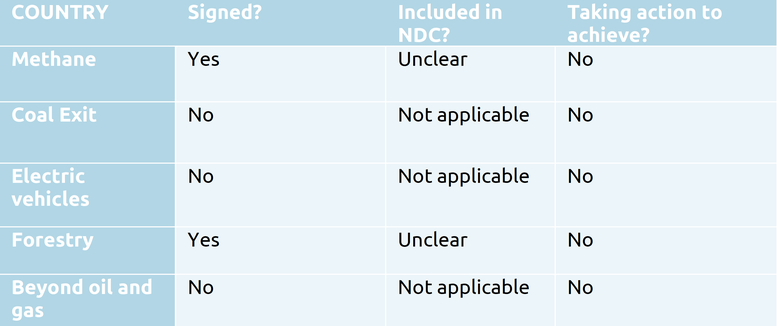

Sectoral pledges

In Glasgow, four sectoral initiatives were launched to accelerate climate action on methane, the coal exit, 100% EVs and forests. At most, these initiatives may close the 2030 emissions gap by around 9% - or 2.2 GtCO2e, though assessing what is new and what is already covered by existing NDC targets is challenging.

For methane, signatories agreed to cut emissions in all sectors by 30% globally over the next decade. The coal exit initiative seeks to transition away from unabated coal power by the 2030s or 2040s and to cease building new coal plants. Signatories of the 100% EVs declaration agreed that 100% of new car and van sales in 2040 should be electric vehicles, 2035 for leading markets, and on forests, leaders agreed “to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030”.

NDCs should be updated to include these sectoral initiatives if they’re not already covered by existing NDC targets. As with all targets, implementation of the necessary policies and measures is critical to ensuring that these sectoral objectives are actually achieved.

| ARGENTINA | Signed? | Included in NDC? | Taking action to achieve? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methane | Yes | Unclear | No |

| Coal exit | No | Not applicable | No |

| Electric vehicles | No | Not applicable | No |

| Forestry | Yes | Unclear | No |

| Beyond oil and gas | No | Not applicable | No |

- Methane pledge: Argentina is one of the 95 countries that signed the methane pledge. While Argentina’s carbon emissions have almost doubled since 1990, its methane emissions have remained relatively stable with current emissions only roughly 5% above 1990 levels (Gütschow, Günther, & Pflüger, 2021). Nevertheless, methane still accounts for 26% of all national GHG emissions in terms of global warming potential, above the global average of around 20% (Global Methane Initiative, 2022). While methane is covered in Argentina’s NDC target, the NDC contains no specific targets nor actions aimed at reducing methane emissions. Current methane emissions are 98.6 MtCO2e, with two thirds related to livestock. Meeting the 30% methane reduction target would mean a 29.5MtCO2e reduction.

- Coal exit: Argentina did not sign the Coal Exit agreement. The country’s electricity generation matrix is dominated by natural gas and large hydro, with coal contributing only around 1.4% in 2019. Argentina has neither plans to phase-out coal, nor a pipeline to develop more capacity.

- 100% EVs: Argentina has no plans to phase-out the sale of ICE vehicles, and did not sign the agreement. Transport emissions in the country are significant, representing 27% of energy-related emissions. The uptake of EVs in the country is very slow: only 55 vehicles were sold in 2021. However, sales of hybrid vehicles are increasing substantially, with around 5800 sales in 2021, and the expectation of further increases once electric vehicles become cost competitive in the country(Bloomberg Linea, 2022).

- Forestry: Argentina signed the forestry pledge at COP26 in 2022. The forest sector is a source of emissions in Argentina, with deforestation being responsible for around 47 MtCO2e in 2018. The country has sectoral plans in place to reduce deforestation, and a system to provide incentives for producers through ecosystem services payments. However, local organisations report that these policies are being under-funded and not properly enforced (Escobar, 2021).

- Beyond oil and gas: Argentina has no plans to stop the exploration and production of fossil fuels. On the contrary, new offshore exploration activities are planned for 2023, and Argentina keeps providing incentives for companies operating at the Vaca Muerta gas field (Government of Argentina, 2022c, 2022d).

Energy supply

Argentina’s energy sector is its biggest source of GHG emissions, reaching 193MtCO2eq in 2018 (54% of the total). Total energy supply increased 78% between 1990 and 2019, and fossil fuels still account for around 90% of the total, mostly gas (52%) and oil (36%). Electricity generation almost tripled in the period 1990-2020, reaching 143 TWh in 2020. While still dominated by fossil fuels, especially gas (54%), in the period 2015-2020, wind and solar PV have taken off, reaching 8% of total generation in 2020, from almost 0% in 2015 (IEA, 2022).

In recent years, Argentina has centred its energy sector strategy around the exploitation of abundant gas reserves in the “Vaca Muerta” formation as a source of cheap oil and gas for national consumption and exports (Secretaría de Energía Argentina, 2018). However, the long-term development of Vaca Muerta remains uncertain even in the context of high oil and gas prices due to increasing political and economic instability and associated risks for investors.

Oil and gas

In 2022, high international fossil fuel prices, resulting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, rekindled interest in Vaca Muerta after two years of low oil and gas prices, which caused production in Vaca Muerta to decline and future developments to be put on hold. According to the government, production of shale oil and gas reached its highest level since 2011 in May 2022, with 245,000 barrels of oil per day, and 76 Mm3 of gas per day, a 57% and 39% increase respectively compared to last year (Government of Argentina, 2022d).

In 2022, the government fast-tracked a previously mothballed project to build a pipeline connecting Vaca Muerta with the national gas network to enable a substantial ramp-up of production. The first stage of the project is expected to be completed during 2023, with an additional pipeline planned for 2024.

These efforts to increase domestic gas production are framed in the Gas.Ar Plan, published in November 2020, which announces the target of producing 30,000 Mm3 of natural gas in four years. This plan includes incentives and benefits for companies looking to produce natural gas and aims to replace imports and save the government USD 2.6bn in fiscal spending and over USD 9bn in foreign currency (Government of Argentina, 2020c).

Additionally, new conventional oil field discoveries off the coast of Namibia have sparked exploration plans off the coast of Buenos Aires. This is because both continents were much closer at the time of the formation of those reserves. First explorations will be led by YPF with Shell and Equinor and will start in 2023. It is expected to find up to one billion barrels of oil (Government of Argentina, 2022c). This would significantly increase Argentina’s reserves, currently at 2.5 billion barrels (World Population Review, 2022).

These developments will most likely impact total emissions in the country through increases in fugitive emissions, as well as creating lock-in of fossil infrastructure and disincentives for a deeper transformation of the energy sector. While their impact on total energy consumption is uncertain, it is possible that increased domestic production of fossil fuels will lead to higher consumption.

The government has made a commitment to the IMF that it will increase its foreign currency reserves and reduce primary fiscal deficit. Replacing gas imports with domestic production is part of the plan to achieve the first, while reducing energy subsidies is key to achieve the second.

In December 2019, the new administration froze electricity and gas tariffs for six months as it developed a new pricing framework and looked to renegotiate contracts with utilities. Amid the COVID-19 crisis and the lockdown, the government extended the term of the capped tariffs until the end of 2020, to then further extend them until the second half of 2022 (National Congress of Argentina, 2019b, 2020).

During the first half of 2022, issue of energy subsidies was a focal point of debate within the governing coalition. In July, the government agreed to implement a segmented tariff scheme to make subsidies less regressive, and possibly save up to USD 500m in subsidy spending in 2023. The new finance minister, Sergio Massa, announced shortly after his appointment that the subsidy scheme would further include a consumption cap of 400 kWh per household per month, beyond which all subsidies would be removed (Diamante, 2022). This is a step in the right direction, but in a context of high political instability, and substantial internal pushback on these reforms, their implementation and future impact is still unclear.

Electricity supply

The former government of President Mauricio Macri introduced various policies that could potentially reduce emissions of the energy sector, including a renewable energy law and a biofuels law (Government of Argentina, 2015b & Government of Argentina, 2016b). The renewable energy law (Law 27.191), published at the end of 2015, aims to incentivise the development of renewable electricity generation and foster the use of renewable energy across sectors. The law establishes renewable energy targets and mandates an 8% share of renewables (including hydro smaller than 50 MW) in electricity consumption by the end of 2017 and a 20% share by the end of 2025 (Government of Argentina, 2015).

An auctioning scheme—RenovAr—is in place to support this target. Up to now, four auctioning rounds have been held (RenovAr 1, 1.5, 2 and 3), leading to the contracting of 4.7 GW of renewable electricity (Morais, 2019). Furthermore, a long-term market for renewable energy (MATER), established through Resolution 281-E/2017, encourages bilateral agreements between energy producers and large-scale consumers. The resolution prioritises the dispatch of renewable generation in case of curtailments due to transmission network congestions (Ministry of Energy and Mining, 2017). The sub-secretariat of renewable energy, which led all these policies and frameworks that paved the way for the entry of renewables, was dismantled in the restructuration of the new government and merged with the sub-secretariat of power energy. Together with PPAs, these three instruments combined have led to the commissioning of 6.5 GW of renewable power in Argentina by 2019.

In April 2019, the Argentinian government announced a fifth round (RenovAr 4), under which it expects to contract around 1 GW of new renewable capacity. In contrast to RenovAr 3, which focused on small-scale renewables with a capacity up to 10 MW per installation, RenovAr 4 will be directed to large scale wind and solar power projects and will include grid infrastructure projects, which are considered a bottleneck for further renewables development in the country (Bellini, 2019). However, the design and timeline of the RenovAr 4 auction have not been defined as of September 2022 and seem to be a low priority for the new government (Djunisic, 2019).

The tightening of capital controls by President Fernandez and the renegotiation of foreign debt with the IMF will likely have an impact on Argentina’s emerging renewable industry, which relies on global finance to thrive. The political risk, the limited access to credits and grid limitations are also discouraging investors and slowing down the growth of the renewable industry (Energía Estratégica, 2020).

The current limitations in the grid put the fulfilment of the renewable targets by 2025 at risk (MAyDS & MINEM, 2017). Concerns about grid limitations had been raised before RenovAr 3, potentially causing a delay in the grid connection of the contracted capacities and making additional auction rounds more difficult to realise. The national grid operator CAMMESA has recognised this issue and is planning on the extension of the electricity grid (CAMMESA, 2018; Télam, 2017).

So far, however, the only measure taken to alleviate this bottleneck has been to make contract conditions more flexible for capacities contracted during previous RenovAr rounds for projects that will not be completed. Resolution SE N°1260/2021 aims to free up transmission capacity from the grid and enable new projects to replace those that will not be completed. It is estimated that between 1.5 and 2 GW of capacity booked in the network is allocated to projects that for different reasons are on stand-by (Energias renovables, 2021).

Announced in COP 26, the Australian firm Fortescue will invest USD 8.4bn in the Argentinian province of Rio Negro to develop green hydrogen. The first phase of the project will generate 650MW and include a wind farm and a port for transportation. It will initially be destined for export, but capacity can be expanded to 8GW in future phases, enabling the dedication of some production for the domestic market. This project fits into a provincial plan to produce 2.2 Mt by 2030 (Garcia Pastormerlo, 2021).

The government has shifted its focus from renewables towards gas and nuclear power. In July 2022, as part of its nuclear plan, the government announced a deal with Chinese manufacturers to start construction of a new nuclear plant with a capacity of 1.2GW before the end of 2022 and plans for the development of an additional plant. The project will cost USD 8.3 billion and will be 85% Chinese financed (Government of Argentina, 2022a).

Agriculture

Agricultural emissions in Argentina were 113 MtCO2e in 2018, accounting for roughly one third of Argentina’s total emissions (excl. LULUCF), and 7% of total energy demand (Government of Argentina, 2022b). The agricultural sector is a major economic powerhouse of the country, and especially to its export market. Key commodities produced in Argentina are soybeans, wheat, maize, and cattle. In total, agricultural commodities represented 71% of Argentinian exports in 2020, and USD 38.6 billion in value.

Despite the high emissions in the sector, Argentina’s national action plan for agriculture and climate change only includes three concrete measures planned for the agriculture, livestock and forestry sector up to 2030, including afforestation (area from 1.38 million to 2 million hectares between 2018 and 2030), crop rotation (increasing the area under cereals (wheat, maize) and decreasing the area under oilseeds (soybeans, sunflower)) and biomass utilisation for energy generation, particularly for off-grid use (Secretaria de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable, 2019a). None of them address the livestock sector, however, which is responsible for over half of the emissions of the agriculture sector, the sector is only mentioned under ‘others’ as a side note with no clear goals or targets.

Considering the high level of methane emissions, combined with the associated deforestation this activity has caused, the agriculture and cattle-ranching sector offers great potential for Argentina to constrain its emissions. This large potential was confirmed by a document published by the Ministry of Agroindustry in 2017, which examines a number of possible measures for mitigating climate change in the agricultural sector, which could improve the productivity of the sector and also reduce land use changes and deforestation linked to agricultural practices and by increasing carbon sinks, including sinks in the soil (Andrade et al., 2017).

Another recent study analyses the potential of supply-side mitigation options to reduce emissions in the agriculture and land use sector including feed optimisation, livestock health monitoring, the use of cover crops and crop rotation, synthetic fertiliser management and the use of silvopastoral systems. It found that the combined technical mitigation potential for these measures was of around 28.1 MtCO2e, or around 14% below the reference scenario in 2030. Compared to a sectoral carbon neutrality in 2050 scenario, the emissions gap was of 103 MtCO2e for 2030 (Gonzales-Zuñiga et al., 2022).

This shows the need for transformation in the sector: even implementing best practices and increasing the efficiency of agricultural production, the sectoral gap to a Paris-compatible emissions pathway is very large. Argentina will need a deeper transformation of its food system if it is to keep its emissions within the 1.5˚C temperature limit.

Argentina’s average share of emissions from LULUCF over the past 20 years are more than 20% of the country’s total emissions. Argentina should work toward reducing emissions from LULUCF, particularly reducing deforestation and to preserve and enhance land sinks.

LULUCF emissions in Argentina were around 39.3 MtCO2e in 2018 according to its Fourth Biennial Update Report (Government of Argentina, 2022b), accounting for 10% of national GHG emissions. LULUCF emissions have been on a downward trend partially thanks to the implementation of the 2007 Native Forests Law (Law 26.331). They decreased by 65% in 2018 compared to 2007 levels but remain a significant source of emissions in Argentina.

Argentina has around 54 million hectares of native forests, as well as 1.3 million hectares of cultivated forests. According to its fourth BUR, in 2018 some 187,000 hectares were lost due to the expansion of agricultural land, forest fires, and overexploitation of forest resources (Government of Argentina, 2022b). The government acknowledges that some of this land clearing is illegal, and the better enforcement of forestry regulations is needed.

The Native Forests Law aims at controlling the reduction of native forest surface, focused on achieving net-zero change in forest areas. The law sets minimum budgets to be spent on forest protection, established a capacity building scheme and requirements for provinces to comprehensively monitor and track forest areas. It also establishes the National Fund for Enriching and Conserving Native Forests that disburses funds to provinces that protect native forests (Law 26331, 2007).

As early as the late 1990s, Argentina implemented Law 25.080 to promote investments in afforestation and preventing forest degradation (Ley 25.080, 1999). According to Argentina’s fourth Biennial Update Report, this law, which has been amended by Law 26.432 in 2008, has contributed to a total of 1.3 million hectares of forest area, with a target of 1.6 million in 2030 (Government of Argentina, 2022b). However, independent sources claim that the program has been de-funded and ecosystem services payments have been greatly decreased in real terms, and its effectiveness to continue to support afforestation and preservation is at risk (Escobar, 2021).

In 2018, and in the frame of the UN REDD+ program, Argentina has submitted its National Action Plan on Forests and Climate Change (PANByCC), which includes a target of 27MtCO2eq reduction from land use emissions by 2030 (UNREDD, 2022).

Alongside the implementation of its PANByCC, Argentina launched its ForestAr 2030 initiative, which aims to develop a broad stakeholder dialogue and strategy to conserve natural forests and to deliver on the country’s commitment to reducing climate change while achieving other sustainable development benefits.

The stakeholders’ agreed vision is to use forests sustainably by 2030, generating opportunities which strengthen the regional economies (Gobierno de Argentina, 2018b). In the context of this initiative, the government created the National Plan for the Restauration of Native Forests through Resolution 267/2019, which seeks to restore 20 million hectares of native forest per year by 2030 (Resolución 267/2019, 2019).

Industry

Between 1990 and 2018, direct emissions from industry in Argentina rose from 29.7 MtCO2e to 54.6 MtCO2e, i.e. by 86%, according to the Fourth Biennial Update Report (Government of Argentina, 2022b). Over this period, activity-related GHG emissions increased by 157%, while energy-related emissions increased by 58%. In 2018, the total contribution of Argentina’s industry sector (54.6 MtCO2e) to total national emissions (excluding LULUCF) was around 16% and represented 23% of total energy demand.

The biggest subsectors by production value are food and beverage manufacturing (31%), construction (14%) and manufacture of chemical substances and products (12%). The industrial sector is also the biggest consumer of natural gas after thermoelectric generation plants. However, most process-related emissions stem from steel and cement production.

The Renewable Energy Law 27.191, adopted in 2015, also specifically fosters the use of renewable energy in the industry sector. It mandates all large-scale electricity users to comply with the renewable energy targets, i.e. 20% of national electricity consumption by 2025. Users can either do so by purchasing electricity from the wholesale market or by signing third-party power purchase agreements with independent renewable energy producers. While the policy will not have an impact on direct emissions from the industry sector, it will support emissions reductions of electricity generation. Resolution 281-E/2017 furthermore encourages bilateral agreements between energy producers and large-scale consumers (with electricity demand greater than 300 kW) through a long-term market of renewable energy (MATER) (Ministry of Energy and Mining, 2017).

To boost energy efficiency in the industry sector and beyond, the Argentinean government developed the Argentinean Fund for Energy Efficiency (FAEE) in 2009. One of the objectives of this fund is to improve energy efficiency among small and medium enterprises (SMEs) through energy audits.

While subsidies for electricity consumption of SMEs have significantly decreased over recent years, the government granted new subsidies to large-scale users in 2017. Through Joint Resolution 1-E/2017, the Ministries of Energy and Industry award a discount of up to 20% on electricity prices for energy-intensive industries until the end of 2019 (Ministry of Energy and Mining, Ministry of Industry, 2017).

At the same time, the government seeks to promote energy management systems for industrial companies. In 2018, the Ministry of Energy passed Provision 3/2018, which establishes that companies benefitting from reduced electricity prices under Resolution 1-E/2017 have to implement the ISO norm 50001 on energy management systems, including the development of an energy management action plan, energy performance targets and indicators to monitor progress (Ministry of Energy and Mining, 2018).

Transport

In 2018, emissions from the transport sector in Argentina represented 16% (~51 MtCO2e) of Argentina’s GHG emissions (excluding LULUCF) according to the Fourth Biennial Update Report, and approximately 31% of energy demand.

Since 2008, the government has incentivised the use of public transport in large urban areas through the development of Bus Rapid Transit Systems (BRTS). As of 2020, 18 BRTS are in place, with a goal to reach 20 by 2030 (Government of Argentina, 2022b).

In 2015, the government passed Law 27.132 which stresses the importance of increasing rail transport in the country (Ley 27.132 - Política de Reactivación de Los Ferrocarriles de Pasajeros y de Cargas, Renovación y Mejoramiento de La Infraestructura Ferroviaria, Incorporación de Tecnologías y Servicios., 2015). In June 2018, further steps were taken to facilitate access to new private freight transport operators and promote large-scale investments in railways (enel Subte, 2018). At the same time, however, the government is also promoting road infrastructure, e.g. through the ‘Plan Vial Federal’, which may undermine the climate goals in the transport sector (Climate Action Tracker, 2019).

For fuel switch, the Biofuels Law 26.093, in force since 2006, promotes the use and production of biofuels through blending mandates and fiscal incentives for biofuel producers (Ministry of Justice and Human Rights, 2006). The blending mandate for biodiesel was set at 10% as established in Resolution 44/2014 (Resolución 44/2014, 2014), while Resolution 37/2016 required a minimum 12% of bioethanol blend in transport fuels from 2016 (Resolución 37/2016, 2016).

In 2021, the government updated biofuel blending mandates, reducing biodiesel blending from 10% to 5%, with the option of being further reduced to 3% depending on how input prices after final fuel prices for consumers. A recent study has calculated that this reduction can lead to increasing cumulative emissions by 7.9-11.7 MtCO2e in the period 2021-2030 (Magnasco & Caratori, 2021). However, a reduction in the production of first-gen biofuels can also have positive effects in land related emissions, reducing the pressure to expand agricultural lands and demand for the commodities used as feedstock (Rulli et al., 2016).

In 2018, the Ministry of Transport passed Decree 32/2018 which modifies the National Transit Law (Law 24.449) in order to include EVs in the regulatory framework (Gobierno de Argentina, 2018a). In 2017, Decree 331/2017 reduced the tariffs on EVs to encourage the import of up to six thousand EVs in the three following years (Gobierno de Argentina, 2017). In 2018, Decree 51/2018 was adopted which eliminates the import duty rate on electric buses destinated for pilot projects (Decreto 51/2018, 2018). In March 2021 the government also introduced a new mandatory light-duty vehicle label to reflect fuel efficiency and emissions in all new vehicles under 3.500 kg.

The uptake of EVs remains low in Argentina, but it is slowly picking up due to incentive policies. In 2021, the Argentinian Association of Automobile Dealerships reported 5871 new sales of low-emissions mobility light-duty passenger vehicles, out of which 99% where hybrid cars and only 1% plug-in EVs (Bloomberg Linea, 2022).

Buildings

In 2018, emissions from the buildings sector in Argentina represented 8% (~28 MtCO2eq) of Argentina’s GHG emissions (excluding LULUCF) according to Fourth Biennial Update Report. They grew by 60% between 1990 and 2018. Residential buildings played a major role in this increase, almost doubling from 13.5 MtCO2e in 1990 to 24 MtCO2e in 2018, while emissions from commercial and institutional buildings remained stable at around 4 MtCO2e/yr. In 2018, buildings represented around 25% of energy demand.

As a response to the COVID-19 crisis, the government has allocated ARS 100 billion (USD 1.4 billion approximately) for the construction and refurbishment of buildings, schools and hotels. However, the measure is not accompanied by sustainability and energy efficiency guidelines (Government of Argentina, 2020a).

Since 2017, several pilot programmes set up by the Argentinean government have been underway in a few cities such as in the city of Rosario, aiming at validating the efficiency norms to subsequently apply them as public polices at the national level (Climate Action Tracker, 2019). Targeting infrastructure more directly, the Efficient Public Lighting Plan (PLAE), launched in 2017, aims to reduce emissions from street lighting by 50% (Ministerio de Energía y Minería Argentina, 2007).

In 2017, the government adopted Law 27.424 to promote the use of renewables in the building sector. The Law encourages small-scale electricity users (residential and commercial) to produce their own energy from renewable resources. This law encourages self-consumption of electricity through the introduction of net-metering (Ley 27424 - Régimen de Fomento a La Generación Distribuida de Energía Renovable Integrada a La Red Eléctrica Pública, 2017). The implementation of these incentives is supported by the Distributed Renewable Generation Fund (FODIS) which provides loans, lower interest rates, and encourages research and development (Climate Action Tracker, 2019).

In 2018, the government adopted an energy efficiency labelling scheme for residential housing, aiming at improving access to information for consumers and incentivise efficiency improvements. The voluntary certification had been applied to 1400 households by 2019 and is still being implemented although no further updates have been provided.

With a view to household appliances, Resolution 319/99 set up an energy labelling scheme in 1999, which has been amended several times (Resolución 319/99, 1999). Furthermore, the labelling scheme defined in PRONUREE was complemented with Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS) for certain appliances (Secretaría de Energia, 2018). Law 26.473, passed in 2008, bans the import and commercialisation of incandescent lamps for residential use as of 2011 (Law 26473, 2008).

Waste

Between 1990 and 2018, Argentina’s waste emissions more than doubled, accounting for 6% (19.3 MtCO2e) of Argentina’s total GHG emissions in 2018. Waste production is in the order of 1kg per person per day in Argentina (Government of Argentina, 2022b).

In 2005, Argentina implemented a National Strategy for the Management of Urban Solid Waste (ENGIRSU). Its objectives are to reduce, reuse and recycle waste as well as to avoid landfills in order to protect the environment (Ministerio de Salud y Ambiente Argentina, 2005). However, the implementation of norms regarding waste management falls within the jurisdiction of Provinces, which can lead to disparities in its enforcement.

In 2021, the Environment Ministry released resolution 290/2021 establishing the National Programme to Strengthen the Circular Economy. This policy aims at improving waste collection and treatment systems, reducing waste and increasing recycling rates. To date, no policies have been implemented in Argentina to directly reduce GHG emissions from waste.

According to Argentina’s Fourth Biennial Update Report, there has been progress on segmented waste collection and treatment. Big urban centres have also implemented systems to capture and store or destroy methane from waste, while in the rest of the country, solid urban waste is still disposed of in open landfills without sanitary treatment.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter