Pledges And Targets

Summary table

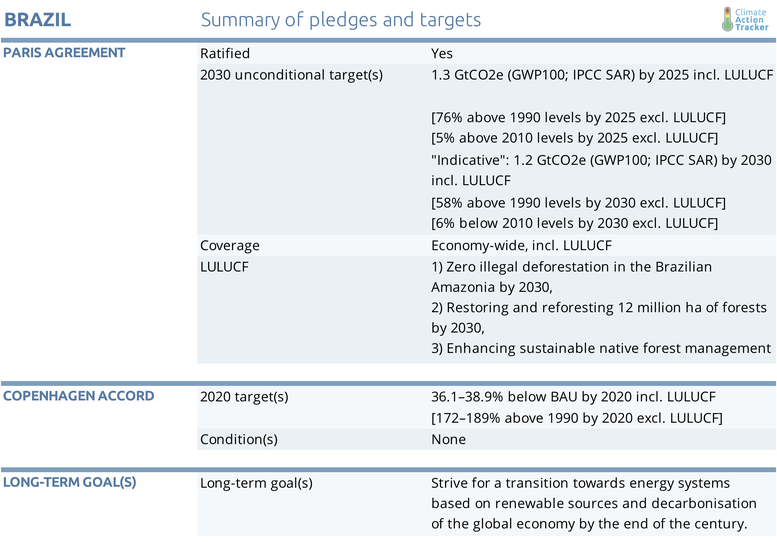

Paris Agreement

Brazil ratified the Paris Agreement on September 21, 2016, committing to reduce emissions to 1.3 GtCO2e by 2025 and 1.2 GtCO2e by 2030 (Government of Brazil, 2015), as stated originally in its INDC (Intended Nationally Determined Contribution), which is equivalent to 37% and 43% below 2005 emissions levels including LULUCF (GWP-100; IPCC AR5).

While the nominal reduction targets appear to be challenging and ambitious at first glance, after taking into account that the base year for the NDC targets (2005) was a year with particularly high emissions, the real target represents very little effort beyond current ambition levels. Between 2005 and 2012, LULUCF emissions decreased 86% in Brazil thanks to the successful implementation of anti- deforestation policies, resulting in a decrease of 55% in total net emissions in the same period. This means that the NDC effectively translates to a decrease of only 7% in emissions incl. LULUCF below 2012 levels by 2030.

The CAT assesses emissions excluding LULUCF, and shows emissions from LULUCF separately. We rate governments only based on emissions excluding the LULUCF sector. Taking into account the strong decrease observed in LULUCF emissions between 2005 and 2012 and the projected emissions levels for this (Ministério da Ciência Tecnologia Inovações e Comunicações Brasil, 2017), the CAT estimates that the NDC targets translate to an increase in non-LULUCF emissions above 2005 levels (GWP-100; IPCC AR4) of 17% in 2025 and a 5% increase in 2030 (equivalent to 76% and 58% above 1990 levels [GWP-100; IPCC AR4]).

In previous versions of our assessment we used LULUCF emissions projections consistent with the REDD PAC model, as used originally by the Brazilian Government for the formulation of the NDC (REDD and Policy Assessment Centre, 2015). However, due to methodological differences and modelling assumptions, the Brazilian Government has abandoned the REDD PAC model in its discussion on how to implement the NDC. Since early 2018, we have updated our LULUCF emissions projections to reflect the Brazilian Government’s most recent modelling exercise (Ministério da Ciência Tecnologia Inovações e Comunicações Brasil, 2017), which has higher emissions projections from this sector than in the REDD PAC model.

Copenhagen Pledge for 2020

Brazil was one of the first major developing countries to put forward an emissions reduction target with its Copenhagen pledge in January 2010. It committed to reducing its emissions incl. LULUCF by between 36.1% and 38.9% in 2020, compared to BAU emissions. This target is equivalent to a 172–189% increase on 1990 levels excl. LULUCF. The target was turned into national law in December 2010, which contained no conditionality on international funding, making it more stringent than Brazil’s international target (Presidência da República, 2010).

However, there was also a difference in the proposed BAU: it increased. Whereas Brazil’s Copenhagen Pledge suggested a BAU level of 2.7 GtCO2e/a by 2020, its national law includes a BAU level of 3.2 GtCO2e/a with the same percentage reduction. That translated into a 20% increase of 2020 emissions levels compared to the Copenhagen Pledge.

The Brazilian government has recently claimed the achievement of the 2020 LULUCF pledge three years ahead of time (Observatório do Clima, 2018b). While the statement is factually true, there are a number of caveats that should be considered:

- Brazil had already achieved most of the deforestation reductions of the 2020 pledge in 2012 (see also our previous assessments). Since then, LULUCF emissions have started increasing again.

- The BAU emissions pathway used as reference for the 2020 pledge assumes very high emissions. The BAU pathway itself is based on an inflated projection, making an assumption of 5% annual GDP growth after 2010 (Presidência da República, 2010), which is far above actual developments (The World Bank, 2017).

- To achieve its pledge, Brazil has proposed a series of measures and policies targeting the LULUCF sector and, notably, the government has committed to reducing annual deforestation rates by 80% below average levels 1996–2005 by 2020. These reductions are far from being achieved according to recent government figures. For instance, the 80% deforestation reduction in the Amazon specified in the Decree would mean 3,907 km² deforested per year, but, in the 12 months to July 2017, 6,947 km² were lost.

- The reversal in LULUCF policies by the outgoing government, expected to be made worse by the incoming government, is projected to have negative consequences for deforestation, potentially causing Brazil to miss its 2020 and NDC deforestation targets by a large margin (Rochedo et al., 2018; Soterroni et al., 2018) To illustrate this, we have added alternative projections for LULUCF produced by national experts (Rochedo et al., 2018) to our main graph, and calculated the indicative 2020 non-LULUCF emissions target that would be required if LULUCF emissions were to follow this trend, instead of the official government projections.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter