Country summary

Overview

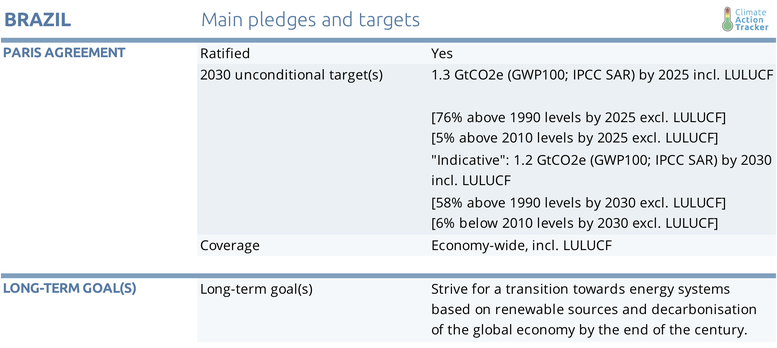

President Bolsonaro’s administration is at odds with the urgent need for climate action in Brazil. Current energy infrastructure planning which foresees a very important role for fossil fuels in the decades to come and the developments in the Land Use and Forestry sector reflect a worsening of national climate policy implementation and ambition. Brazil will need to implement additional policies to meet its economy-wide NDC targets.

Brazil’s remarkable progress in forestry emissions mitigation observed since 2004 has stopped, and deforestation and resulting emissions increases have recently picked up speed again, with the 2019 dry season breaking records in deforestation and forest fires. The Bolsonaro administration, supported by “ruralist” legislators who have traditionally opposed forest protection policies, has continued with the weakening of environmental institutions, including substantial budget cuts, which has severely reduced Brazil’s ability to monitor, inspect, and prevent environmental crimes, including illegal deforestation.

While it’s hard to predict the exact effect of these changes on emissions, most of them have the potential to drive up environmental offenses, as evidenced by the most recent monitoring data. Given the key role of the Land Use and Forestry sector in Brazil’s NDC and the huge global importance of its forests for environmental services, biodiversity, and carbon sequestration, the Brazilian government urgently needs to strengthen mitigation action in this sector—instead of weakening it.

The current administration has not implemented any new policies to halt emissions growth in other sectors. This is illustrated by the situation in the agriculture sector, which is the second largest contributor to Brazil’s GHG emissions. One of the key drivers of increasing deforestation is the expansion of the agricultural frontier and cattle ranching areas. While historical data shows that expanding the agriculture frontier through deforestation is not necessary to increase productivity and adding value and productivity in agriculture can be achieved by investment in more sustainable and efficient agriculture methods, we find no new policy instruments or regulations to advance implementation of emissions mitigation in this critical sector.

For the energy sector, while Brazil is well on track to overachieve its indicative NDC sectorial targets under current policy projections, energy emissions are projected to grow around 15% from current levels by 2030.

Despite government inaction, market trends for renewable energy are positive in Brazil. The latest national energy auction for new capacity, held in October 2019, resulted in three quarters contracted being awarded to renewable energy, with solar (which was allowed to participate for the first time) offering the lowest price of all (21 USD/MWh), followed by wind (24 USD/MWh). The only contracted energy from fossil fuels came from two gas power plants which offered a price almost twice as high as solar and wind.

While market developments bring hope for renewable energy developments, policy developments may ultimately limit the options for long-term deep decarbonisation of the economy as a consequence of unnecessarily locking Brazil in a carbon-intensive energy infrastructure.

The current energy infrastructure planning is a source of concern as it appears to continue favouring fossil fuels, including coal and gas, as opposed to what is required under the Paris Agreement. A clear example of this are Brazil’s plans for fossil fuel production, set to expanding substantially in the next decade, with a large part of this expansion coming from as yet unexploited unconventional resources.

According to our most recent assessment, Brazil will need to implement additional policies to meet its NDC targets, and with current policies is expected to reach emissions levels (excluding LULUCF) of 1,056 MtCO2e in 2025 and 1,088 MtCO2e by 2030 (respectively, 25% and 28% above 2005 levels). Emissions in most sectors are expected to rise at least until 2030 and the current administration has not implemented any new policies to halt emissions growth.

The main policy instruments included in our current policy projections pathway are the energy efficiency national plans and the incentives for the uptake of renewables in the energy sector, including capacity auctions in the power sector, and the ethanol and biodiesel mandates in the transport sector, as well as the national biofuels policy RenovaBio. Brazil has enacted other sectoral plans to reduce emissions in other sectors of the economy, but was most of those policies and instruments are still not part of national development planning or regulation, we have not included in our current policy projections emissions pathway.

On forestry, in 2018, Brazil recorded the world’s highest loss of tropical primary rainforest of any country, reaching 1.3 million hectares, largely due to deforestation in the Amazon. National estimates show total deforestation reaching 7,900 km2 in 2018, which is an increase of 13.7% from 2017 levels, and 72% from the historic low reached in 2012 (PRODES, 2019).

The 2019 dry season breaking records in deforestation and forest fires, despite weather conditions being milder than in previous years, point to an increase in anthropogenic causes, including illegal deforestation. This trend takes Brazil in the opposite direction of its Paris Agreement commitments, which include a target of zero illegal deforestation in the Amazonia by 2030.

On energy, under current policy projections, the indicative NDC target of a 45% share of renewables in the total energy mix by 2030 will be overachieved, with renewable energy expected to represent 47% of the energy mix in 2027 and 48% in 2029 according to the most recent energy plan. However, unless additional policies are put in place, emissions in the energy sector will continue to rise, leaving the huge national potential for renewable power generation untapped.

On transport, while biofuels have contributed significantly to improve the emissions intensity of the road transport sector in Brazil, full decarbonisation of the transport sector will require a fast uptake of electric vehicles (EVs). In terms of EVs, Brazil is a laggard, with a very small penetration rate and without a clear strategy to substantially increase the adoption of this technology.

To peak emissions and rapidly decrease levels afterward as required by the Paris Agreement, Brazil will need to reverse the current trend of weakening climate policy, by sustaining and strengthening policy implementation in the forestry sector and accelerating mitigation action in other sectors— including a reversal of present plans to expand fossil fuel energy sources.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter