Policies & action

Canada’s emissions are finally starting to trend downwards as the government continues to implement its climate policy agenda, but there remains a significant gap between current policies and Canada’s NDC target. Implementing planned policies will contribute significantly to closing that gap, but further action is needed.

Our rating of Canada’s policies and action has improved to “Insufficient”, with the latest emissions projections showing significantly lower expected emissions for 2030. That said, it is still far from 1.5°C compatibility on a global least cost basis. If all countries were to follow Canada’s approach, warming could reach over 2°C and up to 3°C.

If Canada can successfully implement all of the measures it has planned, it would go a long way to closing this ambition gap.

Policy overview

The speed and scale of Canada’s climate policy implementation does not match the urgency of the climate crisis and much more work is needed. Emissions in 2030 are projected to be 603 MtCO2e (excl. LULUCF contributions) or 20% below 2005 levels, lower than our last update, due to continued policy implementation, but a far cry from the 377–495 MtCO2e level Canada needs to reach to meet its updated NDC target.

In March 2022, Canada released its latest climate change plan, building on earlier strategies released in 2016 and 2020 (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2020a, 2022a; Government of Canada, 2016b). The measures outlined in the plan are not yet sufficient to ensure Canada meets its NDC target, nor have all been implemented yet. It came on the heels of a damning report in November 2021 by Canada’s Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development outlining 30 years of the government’s failure to meet its targets and reduce greenhouse gas emissions (Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, 2021; Office of the Auditor General of Canada, 2021).

Canada is developing additional policies which are captured in our planned policies scenario. Of the major initiatives (regulations for clean electricity, post-2026 LDV model year standards, oil and gas methane target, and landfill gas), only the EV sales mandate has been implemented since the government released its 2023 projections. Our current policy projection is based on these projections and modified to include the impact of the EV sales target.

A federal election was held on April 28, 2025, with the Liberal Party winning the most seats (Elections Canada, 2025). New Prime Minister Mark Carney was known during his financial career for being forward-looking on the risks posed to the economy by climate change, however uncertainty remains around the new government’s priorities. The Liberals once again have a minority government and will need to rely on the support of other parties to drive forward their policy priorities.

Mandatory carbon pricing had been in effect across Canada since 2019, although the consumer-facing price was zeroed out on April 1, 2025 via regulatory change (Government of Canada, 2018a; Government of Canada, 2025). The industrial carbon price, which is estimated to account for 20-48% of Canada’s emissions reductions in 2030, remains in effect (Canadian Climate Institute, 2025). In preparation for further policy changes, the last government designated almost half of the CAD 15 billion (USD 11bn) in the Canada Growth Fund to be spent on Contracts for Difference or similar offtake agreements to offer stability to investors (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2023a).

The legislation enacting the carbon pricing scheme, the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act, was found to be constitutional by the country’s top court in March 2021 after three provinces challenged it (Supreme Court of Canada, 2021). A second challenge from the province of Manitoba was also dismissed by the Federal Court in October 2021.

Under the scheme, all Canadian provinces and territories must have a cap-and-trade system or carbon tax in place. Jurisdictions without such systems or taxes will fall under the federal backstop. The federal system has two components: a regulatory charge on fossil fuels and an output-based pricing system (OBPS), which applies to major emitting industrial facilities. The federal government will review its carbon pricing benchmark in 2026.

The initial carbon price of CAD 20/tCO2e was set in 2019 and increased by CAD 10 per year, reaching CAD 50/tCO2e in 2022. In its latest climate plan, the government stated it will increase the carbon price by another CAD 15 per year for the 2023–2030 period, reaching CAD 170/tCO2e in 2030 (around USD 125) (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2020a; Government of Canada, 2021k). While the carbon price is heading in the right direction, it is still below the USD 170–290 (2015$) needed to be compatible with 1.5°C (Boehm et al., 2023).

A 2022 audit of the scheme found the government had taken steps to address some of the scheme’s weaknesses, but that requirements for large emitters were poor and could be strengthened (Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, 2022a; Office of the Auditor General of Canada, 2022a).

In June 2022, the federal government established a GHG Offset system for activities not covered by carbon pricing (Government of Canada, 2022e). Credits generated under the system can be used to reduce the compliance costs of industrial facilities covered by the OBPS. At the start the system only covered landfill methane recovery and refrigeration systems, but protocols are being developed for forest management, livestock feed management, enhanced soil carbon, and direct air carbon dioxide capture and sequestration (Government of Canada, 2022c). Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) recently published a draft Reducing Manure Methane Emissions federal offset protocol for a public comment period, ending on April 29, 2025 (Government of Canada, 2025). The ministry is also looking into ways to remove barriers and enhance participation in the system by Indigenous peoples (Government of Canada, 2022f).

Industry

Oil and gas production

At over a third of total emissions, oil and gas production represents Canada’s largest source of emissions (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2024). While the sector’s emissions dropped in 2020 due to the pandemic, they are projected to reach again 2019 levels under current policies by 2030 as production is projected to increase. Canada’s exported emissions from oil and gas are continuing to rise, surpassing its total domestic GHG emissions, and sitting at about 939 MtCO2 in 2022 (Bernstien, 2024). This comes at a time when the IEA has called for no new investments in oil, gas and coal if we are to stay below the 1.5°C limit of the Paris Agreement.

The government seems incapable of kicking its oil and gas addiction. It has promised to set a cap on emissions for the sector, and believes this can be achieved while increasing production. Regulations for the cap are being consulted on in 2024 and are due to be finalised in 2025. They are not yet modelled in our projections. The government is also planning to strengthen methane emission regulations in the sector (see the Methane section below) (Government of Canada, 2023b).

In April 2022, the government approved an offshore oil and gas megaproject, Bay du Nord (Impact Assessment Agency of Canada, 2022a). The project is required to be net zero from 2050 onwards, but production could continue until 2058 (Impact Assessment Agency of Canada, 2021, 2022a). The environment and energy ministers disagree over whether this will be the last development of its kind in Canada (CBC News, 2022). Whether the project will actually proceed is unclear: the company delayed the project by three years amidst concerns over high costs, and challenges to the environmental and economic assessments continue (Canada, 2023; Federal Court of Canada, 2023; Nickel, 2023; Sierra Club, 2024).

The costs of current oil and gas expansion projects continue to rise. The Trans Mountain oil pipeline expansion, due to start operation in 2024 (Calgary Herald, 2023; Trans Mountain Corporation, 2022), is now expected to cost seven times more than when the government first purchased the pipeline (CAD 5.4 bn) (Lindsay, 2021; Williams, 2023). In June 2022, a budget watchdog concluded that it was not viable and would cost the government around CAD 600 million in net losses (Thurton, 2022). Others have estimated that losses will be much higher (The Energy Mix, 2022; Williams, 2023).

Costs associated with the pipeline for the country’s first LNG export terminal, on the country’s west coast, are also soaring (Jang, 2022; Simmons, 2022). While this pipeline is not government-owned, there are questions as to whether it will be able to recoup all of the subsidies provided (Simmons, 2022). The LNG project will only begin exporting fossil gas to Asia in 2025–2026.

Meanwhile, a new anti-greenwashing regulation is causing oil and gas industry associations to scrub their websites of unsubstantiated CCS claims (Noakes, 2024).

Net-Zero Producers Forum

Canada is part of the ‘Net Zero Producers Forum’, along with other oil and gas majors: Norway, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and the US (Natural Resources Canada, 2021a; U.S. Department of Energy, 2021). The forum’s stated aim is to develop ‘pragmatic net zero emission strategies’, including reducing methane emissions and supporting the use of CCS, but it does not tackle the core issue of phasing down production. Beyond holding its first Ministerial meeting and establishing a working group in March 2022, there is little evidence of concrete action more than a year after its formation. Meanwhile, investors and international oil companies continue to exit Canada’s tar sands (Morgan, 2020; Reuters, 2021; The Canadian Press, 2020; Total, 2020; Tuttle, 2022).

Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance (BOGA)

The province of Quebec is a member of BOGA, but Canada as a whole is not. In April 2022, Quebec passed a law banning any further production and mandated that existing drill sites be shut down within three years (Government of Quebec, 2022). The move is largely symbolic as the province is not a producer of oil and gas (Canada Energy Regulator, 2022).

Coal mining

In 2021, the government committed to banning thermal coal exports from and through Canada by 2030 (Liberal Party of Canada, 2021b; Prime Minister of Canada, 2021b). The reference to ‘through Canada’ is important, as many American west coast miners export their coal through Canada due to resistance to developing the export infrastructure in their own country (Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, 2021; Kuykendall, 2021). While establishing the ban is in the trade minister’s mandate letter, he has not yet taken action to implement it (Global Affairs Canada, 2022; Prime Minister of Canada, 2021a). On the contrary, Canadian coal exports soared in 2023, causing the opposition party to call the government to task on this issue (The Canadian Press, 2024a, 2024b).

Canada had been criticised for its hypocritical stance on coal mining, and for not subjecting a thermal coal mine expansion to a federal impact assessment, notwithstanding its position in the Powering Past Coal Alliance (Rabson, 2020). In June 2021, Canada clarified its policy position on thermal coal mining, finding that any new mines or expansions of existing mines would likely cause unacceptable environmental effects (Government of Canada, 2021i). One coal mining expansion project is still attempting to get approval, with environmental groups fighting the government's decision to lift the requirement for an environmental impact assessment (Ecojustice, 2023; Impact Assessment Agency of Canada, 2022b).

Methane

15% of Canada’s emissions come from methane. The oil and gas sector is the largest source (48%) of Canada’s methane emissions, followed by agriculture (27%) and waste (18%) (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2024). The government has committed to reducing methane emissions from the sector by 40–45% below 2012 levels by 2025 and at least 75% by 2030, going beyond the pledges made in its 2022 national methane strategy (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2018, 2021a, 2022d). It adopted regulations to support the 2025 target in 2018 but does not appear to be on track to achieve the 2025 goal (Government of Canada, 2018b, 2023e, 2020c, 2020a, 2020b). Additional regulations to support the 2030 goal were drafted in 2023 and are expected to be finalised in 2024 (Government of Canada, 2022k). The government is confident that they will allow it to reach and even exceed the 75% goal (Government of Canada, 2023d). We have modelled these in our planned policies scenario.

While strengthening its methane targets is a step in the right direction, emissions could be even higher than currently reported. Canada reports on emissions from the sector using bottom-up methods based on internationally agreed standards (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2021b). Research based on atmospheric measurements rather than energy statistics, suggests that emissions could be much higher (Chan et al., 2020; Liggio et al., 2019; MacKay et al., 2021). Canada made improvements to its upstream oil and gas methane emissions estimate methods in its 2022 inventory, which resulted in an upwards revision of emissions of between 31–39% over the last decade (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2022e). It will continue to work to improve measuring and monitoring efforts as part of its national methane strategy (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2022d).

Canada signed the Global Methane Pledge at COP26.

Transport

Transport is the second largest source of emissions in Canada, after oil and gas, representing just under a quarter of the country’s emissions (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2024). In its latest projections and progress reports, Canada foresees transport emissions reductions of 19% below 2005 levels by 2030 (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2023b, 2023a).

Canada is taking steps to reduce transport emissions, but not at the speed needed for such a large source of the country’s emissions. A 2022 ‘action plan’ on road transport did little more than rehash existing targets, plans and funding schemes (Transport Canada, 2022a).

Electric Vehicles

Targets

Canada has had EV sales targets for the past several years. By 2035, 100% of new passenger car and light-duty trucks sales need to be electric vehicles, with interim targets of 20% by 2026 and 60% by 2030 (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2022a). In December 2023, the government adopted the necessary regulations to make these targets legally binding (Government of Canada, 2023g). Plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) are included in the definition of electric vehicles but their contribution to the sales target is capped at 20% from 2028. The sales targets increase in stringency annually, though at a slower pace in earlier years. The GHG impact of the regulations grows over time, but only contributes to minor reductions by 2030 (less than 5 MtCO2e).

In 2023, ~19% of all passenger car and truck sales were EVs, of which 8% were battery electric (Statistics Canada, 2024). Canada should easily achieve its (fairly low) 2026 interim target of 20%.

The CAT has not developed EV benchmarks for Canada; however, our US benchmark suggests that Canada’s targets are not 1.5°C compatible: 95–100% of all US passenger cars and light-duty trucks sold in 2030 should be zero emission vehicles.

The government aims to electrify its own light-duty vehicles LDV fleet by 2030 (Natural Resources Canada, 2022a).

Medium and heavy-duty vehicles

Canada has also set targets for its medium and heavy-duty vehicles (MHDVs) with the goal of achieving a 35% sales target by 2030 and 100% by 2040 for some models (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2022a). Stakeholder consultation on the regulations to make these targets binding has begun, but the timeline for their adoption is not clear (Government of Canada, 2022g, 2023a).

Infrastructure and support programmes

The government began supporting the development of EV-related infrastructure and charging networks in 2016 (Natural Resources Canada, 2021b, 2021c, 2023). Canada has about 26,000 chargers at 10,000 locations across the country (Natural Resources Canada, 2024). Analysis suggests that Canada will need between 440,000-470,000 chargers in 2035 to support its 100% sales target (Dunsky Energy + Climate Advisors, 2022).

The government missed an opportunity to support residential charging infrastructure by not including them in the most recent building codes, though some municipalities are taking action (Kozelj, 2024). Making buildings EV-charger-ready through minor changes at the time of construction can significantly reduce the costs when the necessary equipment is actually installed (Efficiency Canada & Carleton University, 2022).

Since 2019, the federal government has provided rebates for the purchase or lease of EVs and will continue to do so until March 2025 (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2020a; Transport Canada, 2022b). In July 2022, it launched a four-year, half billion CAD programme to support the purchase of medium and heavy duty electric vehicles (Transport Canada, 2022c).

Vehicle emission standards

Canadian fuel economy standards for light and heavy-duty vehicles are aligned with federal-level regulations in the US (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2020a; Government of Canada, 2021h, 2018c). The Biden administration has been working on reversing the Trump era rollbacks, adopting new rules for emissions and fuel standards (see US assessment for details). GHG standards for new trailers have been delayed for several years in response to legal challenges to those standards in the US.

Fuel standards

In July 2023, the Clean Fuel Regulations finally took effect, though are unlikely to have much of an impact until 2025 (Bakx, 2023; Government of Canada, 2022p). The regulations require producers and importers of gasoline and diesel to reduce the carbon intensity of their fuels from 2016 levels, with increasing annual reductions through to 2030.

The regulations create a credit market for compliance, which allows those not subject to the regulations (like EV charging stations or low carbon fuel producers (e.g. biofuels)) to participate. The regulations aim to improve production processes in the oil and gas sector, foster production of low carbon fuels and enable end-use fuel switching in transport. The fuels used by remote communities, and in international shipping, and domestic and international aviation are exempt from the regulation. The renewable fuel content requirements, 2% for diesel and 5% for gasoline, as set out in the Renewable Fuels Regulations, have been incorporated in these new regulations (Government of Canada, 2010).

These regulations were first proposed in 2016 as part of the Pan-Canadian Framework (Government of Canada, 2016a). Originally, standards were also supposed to be prepared for gaseous and solid fuels; however, these were delayed due to industry concerns over trade impacts and have since been shelved (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2020a; Government of Canada, 2017).

Aviation

Canada lacks effective policies to address its aviation emissions, which stand at 22 MtCO2e in 2019. Most of these emissions are not covered by its carbon pricing system, as this pertains to interprovincial travel only, and its clean fuel regulations (see above) do not extend to jet fuel. 70% of Canada’s aviation emissions are from international flights (Government of Canada, 2022b).

In 2022, Canada updated its aviation action plan (Government of Canada, 2022b). As part of the plan, the government commits to exploring ways to consistently apply carbon pricing to domestic aviation emissions.

The plan charts a pathway to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050, in which a shift to Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) is responsible for close to half of the needed reductions. In combination with increased efficiency in equipment and operations, this would offset the expected growth in air travel and bring emissions back to their 2005 levels (around 12 MtCO2e). These residual emissions would then need to be balanced by negative emissions, such as direct air capture. Around 70% of fuel used in 2050 would be SAF with a 90% reduction in lifecycle emissions compared to conventional jet fuel. Lower lifecycle emissions would increase the need for negative emissions outside the sector.

Canada does not produce commercially relevant amounts of SAF currently. In 2023, the airline industry produced a SAF roadmap which is considered an integral part of the government’s aviation action plan. The roadmap charts the requirements for this nascent technology to be able to grow to 25% fuel share by 2035. The roadmap assumes around 50% lifecycle emissions savings in SAF in contrast to the 90% reduction in the aviation plan.

Notably, the aviation plan’s four emission reduction measures are all targeting emission reductions per flight, rather than reducing the number of flights by making other transport modes more attractive. The plan only mentions a new highspeed rail network to connect the airports, rather than incentives to shift travel to rail connections to central stations in the major cities (Government of Canada, 2022b).

Buildings

A little over a tenth of Canada’s emissions are from the buildings sector (excluding electricity) (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2024). Under the climate plan, the government hopes to cut emissions from the sector by 37% below 2005 levels, by 2030, yet emissions have stagnated since 2005 and the last progress report’s NDC-compatible scenario shows 25% of reductions (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2022a, 2023b, 2023a). Provinces, and not the federal government, have jurisdiction over building regulations; however, there is much the federal government can still do to provide direction and support.

The federal government has been active in four key areas under the 2016 Pan Canadian Framework (Government of Canada, 2016b):

1) Creation of a ‘net-zero energy ready’ building code for new buildings,

2) programmes to encourage retrofits and fuel switch in existing buildings,

3) energy efficiency labelling, and

4) standards and renovation programmes in Indigenous communities.

Building on this framework, the government held a consultation in 2022 on a new Green Buildings Strategy aligned with the overall 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan (Government of Canada, 2021j; Natural Resources Canada, 2022b). The three main goals under the strategy are

1) all new buildings to be net-zero carbon ready by 2032 latest,

2) deep retrofit rate to increase to 3–5% per year by 2025,

3) transitioning from fossil-fuel based to electric water and space heating systems.

The Strategy was scheduled for release in 2023 but appears to be delayed.

The new building codes were adopted in 2022, after a two year delay (but are referred to as the ‘2020’ codes) (National Research Council Canada, 2020, 2022a, 2022b). They adopted a tiered system for the first time, which includes a ‘net zero energy ready’ level. (‘Net zero energy ready’ means that the building is efficient enough that a renewable energy system, once added, would be able to provide all of the building’s energy needs). The aim is to move to progressively more stringent tiers so that by 2030 all new buildings are net zero energy ready.

Provinces have agreed to implement this code by 2024 and subsequent updates with a year and a half from publication (Efficiency Canada & Carleton University, 2022). While the codes are heading in the right direction, they are missing key elements: there are no GHG emission requirements, nor provisions to support renewable or EV readiness, though GHG emissions will be addressed in the next update cycle (Efficiency Canada & Carleton University, 2022; Natural Resources Canada, 2022b).

As 80% of the buildings stock that will exist in 2030 has already been built (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2022a), accelerating energy-efficient renovations and retrofits is crucial to decarbonising the sector. Canada has several programmes which support its goal of a 3–5% deep retrofit rate, including CAD 200m for a Deep Retrofit Accelerator Initiative for large buildings (Natural Resources Canada, n.d.), but additional measures are likely needed to achieve this goal. While we have not undertaken this analysis for Canada, the CAT estimates the USA and the EU would need to renovate at least 3.5% of the existing buildings stock per year to be compatible with the 1.5°C temperature limit.

The government has also been slowly updating its energy efficiency regulations for a number of residential and commercial products (water heaters, furnaces, etc) and is planning a further round of revisions (Government of Canada, 2022l, 2019c, 2019b). Often the regulatory updates seek to align with existing standards in the USA. As part of the Green Buildings Strategy, it will adopt regulations to prohibit the installation of new oil or fossil gas heating systems and will develop incentives to accelerate heat pump adoption.

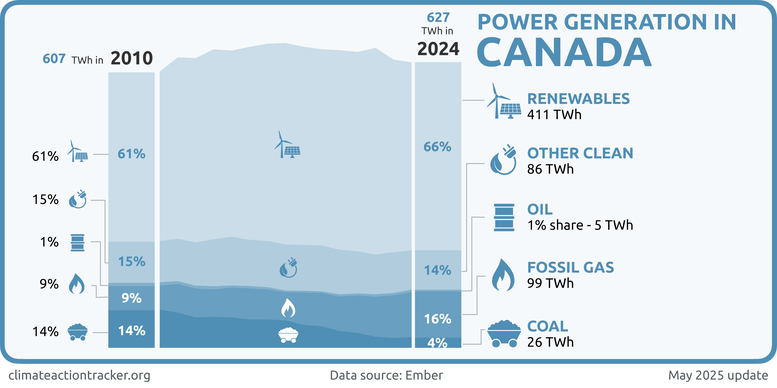

Power sector

Electricity generation is responsible for less than 10% of Canada’s emissions. Its share of the country’s emissions has been falling since 2015 as Canada shifts away from coal (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2023b). Canada’s Clean Electricity Strategy and Clean Electricity Regulations were fnalised in December 2024, pushing back Canada’s initial net zero electricity grid target from 2035 to 2050 (Government of Canada, 2024).

To be 1.5°C compatible, Canada would need to phase out all fossil fuels in the power sector by 2035 (Climate Action Tracker, 2023a). The CAT does not see a role for CCS in the power sector, given its high cost, low technological maturity and residual emissions (Climate Action Tracker, 2023b).

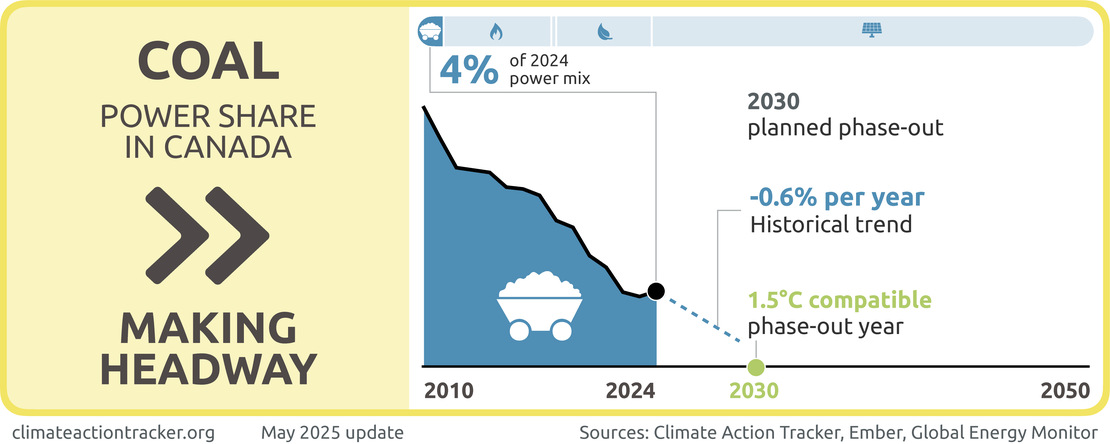

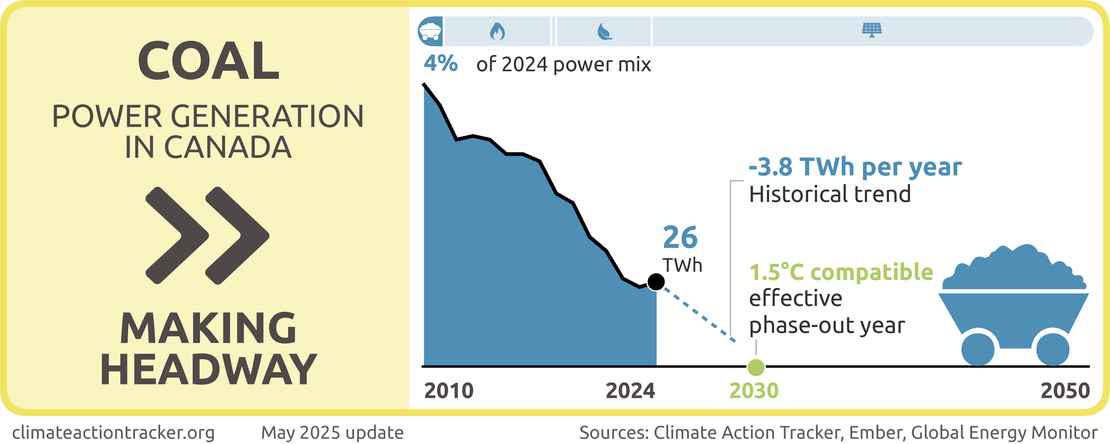

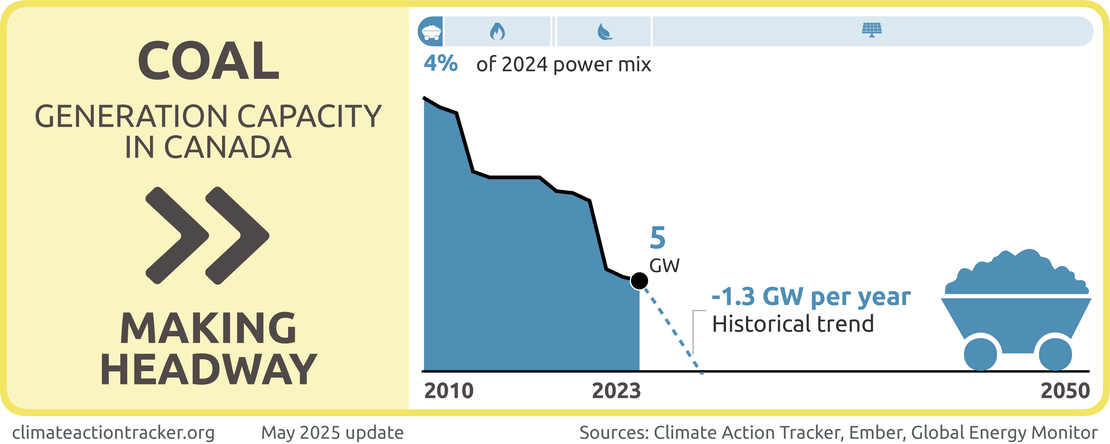

Coal power phase out – almost, but not quite

We evaluate Canada as "Making headway" on coal power. Coal generation has decreased significantly over the last 5 years, with coal's share of the overall power mix also steadily declining. Canada co-founded the Powering Past Coal Alliance in 2017 and has had a regulatory system in place since 2018 to phase out “unabated” coal power by 2030. Canada is on track to achieve this phase-out target. Currently only three of Canada’s ten provinces still generate power from coal. Alberta phased out coal-fired generation in 2024, well ahead of its initial commitment of 2030 (Natural Resources Canada, 2023b).

While Canada's coal phase-out efforts are positive, there are some limitations. Current regulations still allow for plants which emit up to 420 gCO2/kWh, roughly half the emissions intensity of conventional coal power (Government of Canada, 2018d). However, the regulations are designed to allow for coal-fired power generation with carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology.

The CAT does not see a role for coal power with CCS for three main reasons:

- CCS does not remove 100% of emissions from power plants

- Heavily relying on unproven CCS for power generation simply prolongs the use of fossil fuels, diverting attention and resources away from the necessary and urgent switch to renewable energy generation that drives down actual emissions.

- The use of CCS should be limited to industrial applications where there are fewer options to reduce process emissions—not to reduce emissions from the electricity sector where renewables are cost-effective mitigation alternatives

Canada’s experience with CCS at Saskatchewan’s Boundary Dam coal plant since 2014 demonstrate these challenges, as it has been plagued with technical and operational problems and has still not met its annual CO2 capture target (Rives, 2022; SaskPower, 2022b, 2022a; Schlissel, 2021; Taylor, 2019).

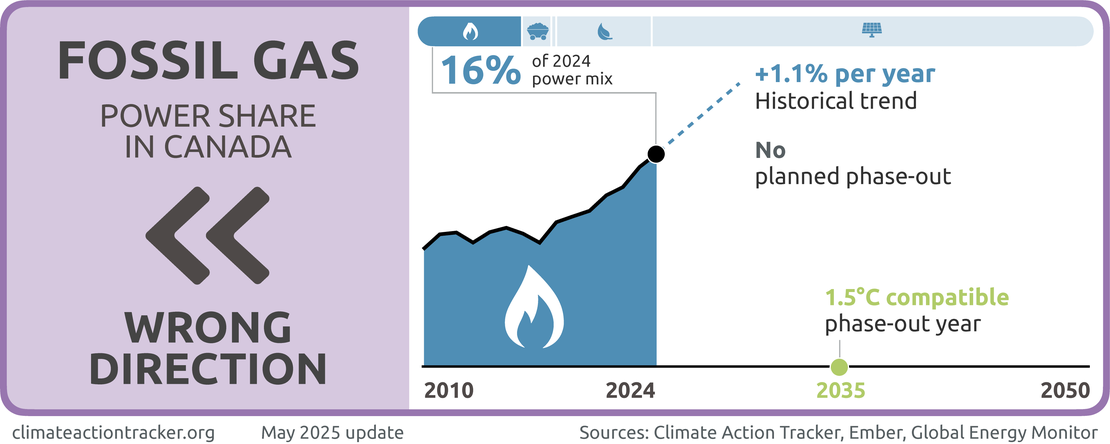

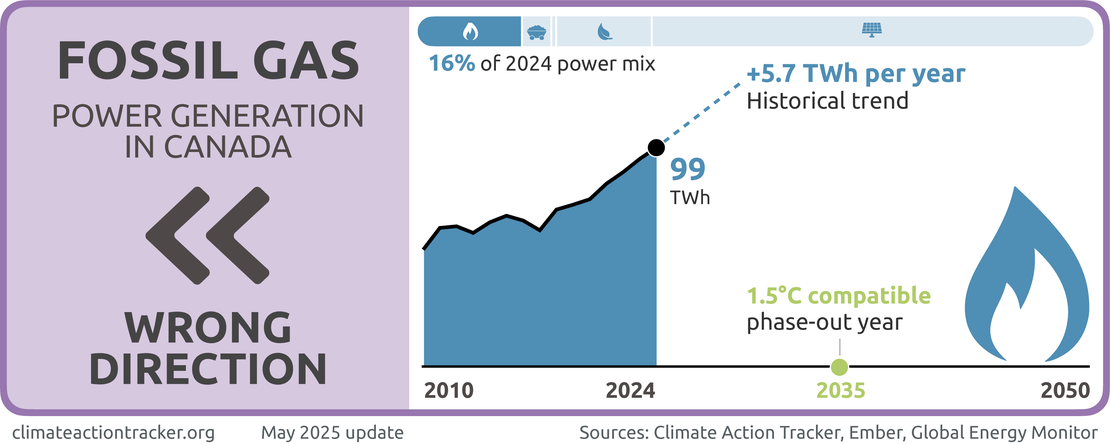

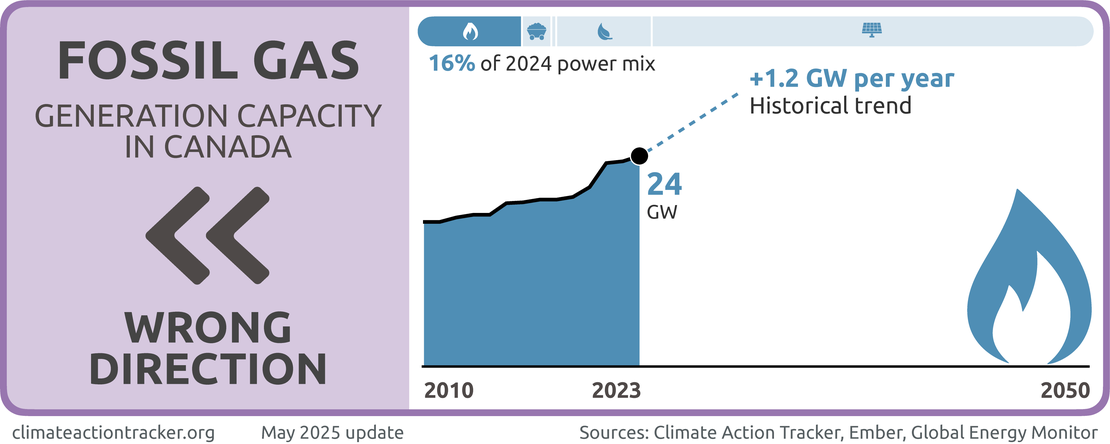

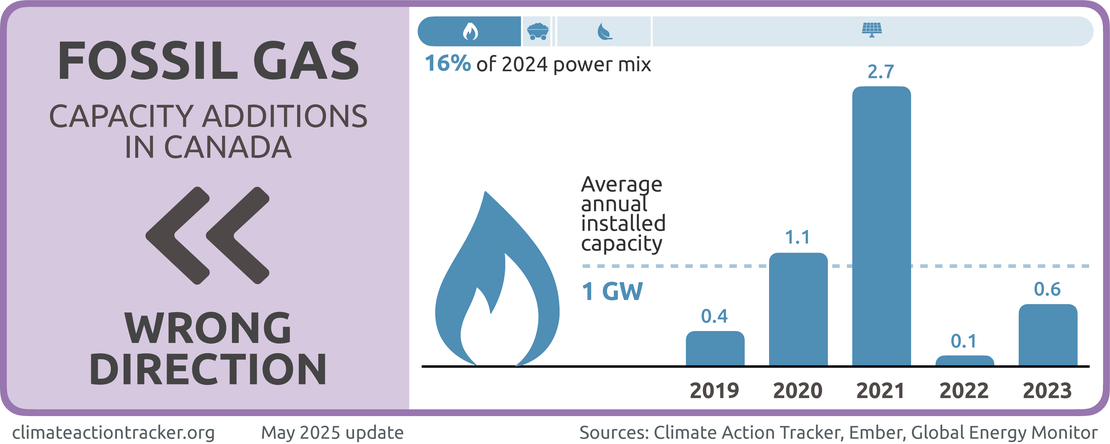

Fossil gas power phase-out

Canada is moving in the "Wrong direction" on fossil gas. Electricity generated from fossil gas has increased over the last five years, with fossil gas's share of the overall power mix also rising steadily. This trend runs counter to what is needed for 1.5°C compatibility, which would require developed countries like Canada to phase out unabated fossil gas by 2035.

Canada introduced new Clean Electricity Regulations in December 2024 to operationalise the 2050 net zero emissions electricity grid target established in the Clean Electricity Strategy. The Regulations update emissions performance standards for all grid-connected fossil-generated electricity above 25 MW capacity (Government of Canada, 2022g, 2023a, 2018e). Government projections estimate the Regulations will result in 180 MtCO2e emissions reduction between 2024-2050.

The regulations contain concerning exemptions and flexibility provisions. Exemptions will apply in cases of emergencies, when fossil gas without CCS may be used, and for remote northern communities (where much of the power is diesel generated). For older facilities, only emissions that exceed the sector benchmark of 370 gCO2/kWh need to be offset. Planned units which are under construction by 31 December 2027 and meet certain criteria will be allowed to operate without an Annual Emissions Limit until the end of 2049 (Government of Canada, 2024).

Canada continues to build and rely on fossil gas in its power sector. Cascade Power, a 900 MW fossil gas plant, due to start operation in 2024 could fall under such an exception (Cascade Power, 2021). SaskPower is also building new fossil gas plants to come online in 2024–2026 (SaskPower, 2022a). Continuing investment in fossil gas infrastructure is concerning, especially given that the cost of fossil gas is expected to increase further, while renewable electricity generation continues to get cheaper. Fossil gas in generation has increased significantly over the last five years, rising an average 5.74% per year. This is not compatible with the 1.5ºC limit, which would require developed countries like Canada to phase out unabated fossil gas by 2035.

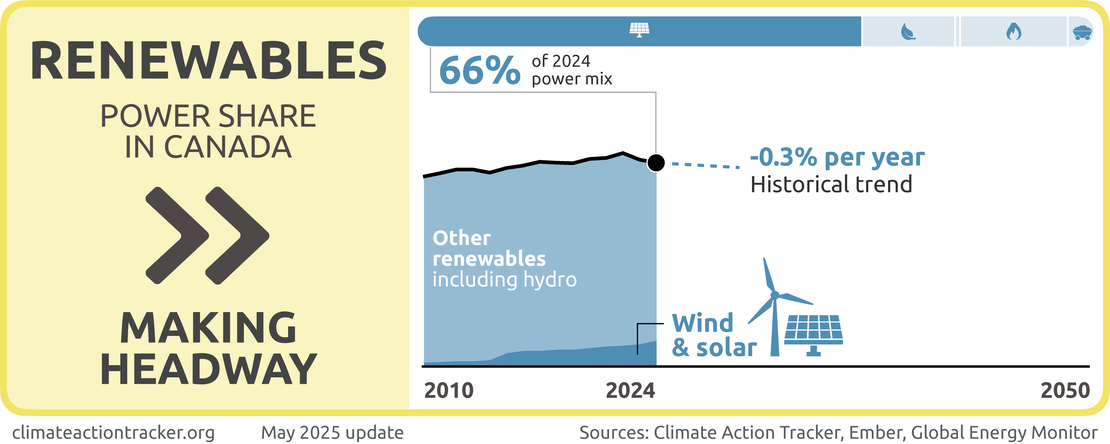

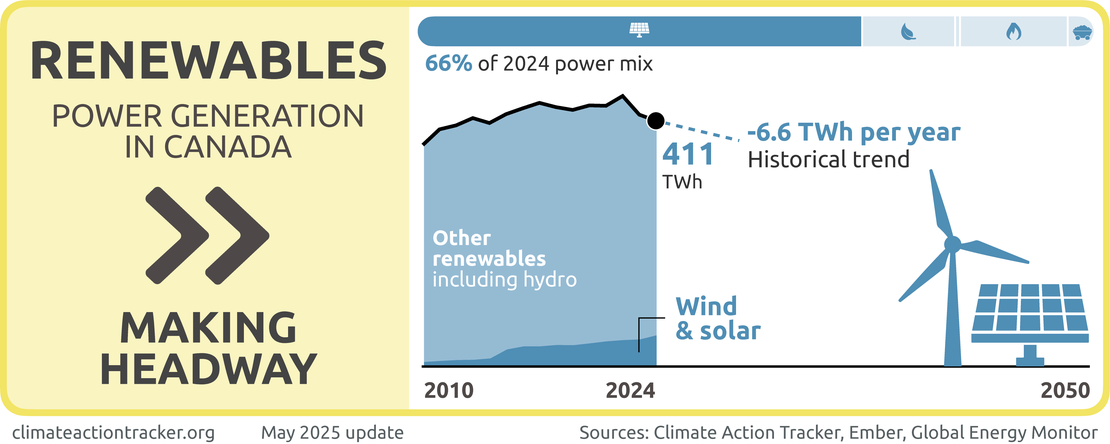

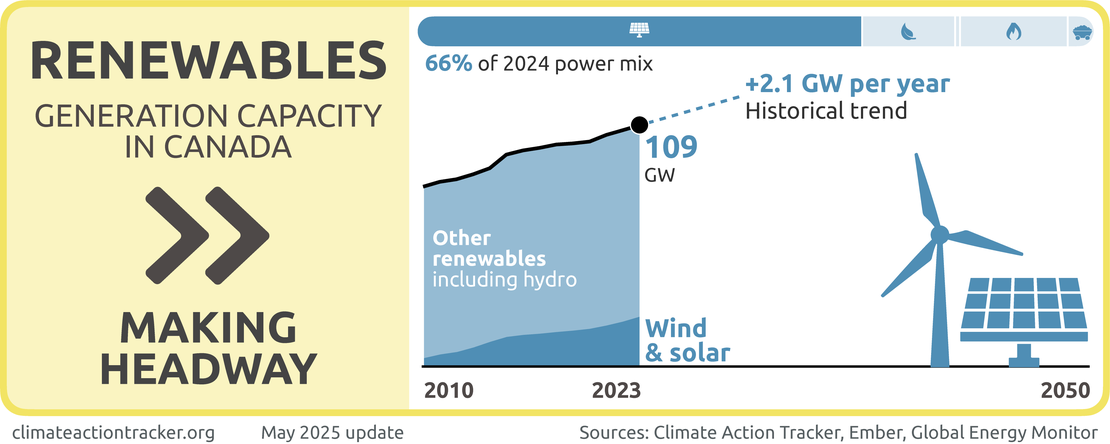

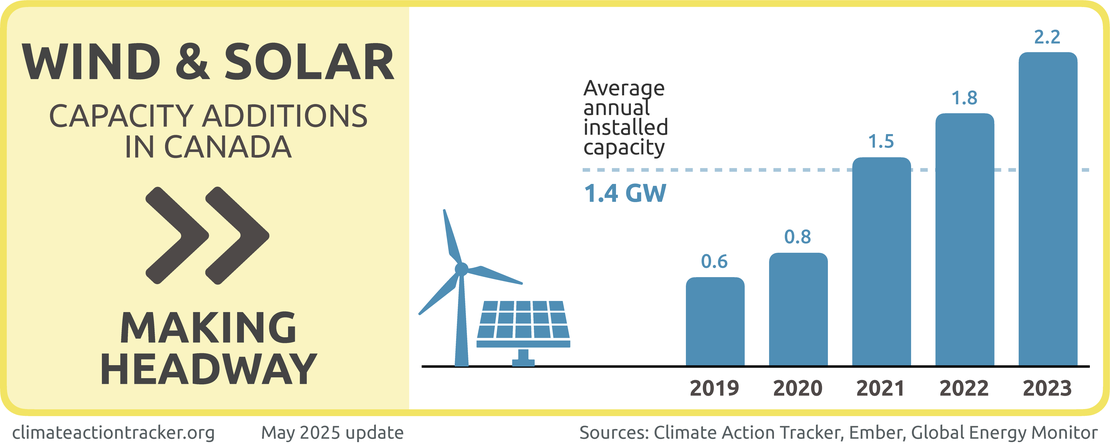

Renewables

Canada is "Making headway" on renewables. The share of wind and solar in the power mix has been increasing over the last five years, with a nearly 3 TWh increase per year in overall power generated from these sources. Two-thirds of Canada’s electricity is already renewable, due to a long legacy of hydropower that still supplies 60% of demand. Wind and solar power are increasing fast, having grown from 2% to 7% market share in the last decade. Another 15% is nuclear power, leaving less than 20% to be supplied from fossil sources (IEA, 2023).

Despite this strong starting position for achieving an early carbon-free grid, under current policy, Canada is expected to use gas for power generation beyond 2030, betting on CCS to deliver on its promise of a net-zero emissions grid by 2050. To be fully 1.5°C compatible, Canada would need to accelerate its renewable deployment to phase out all fossil fuels in the power sector by 2030 (Climate Action Tracker, 2023a).

Canada has several funding programmes for ‘clean electricity’ projects, including renewables, nuclear and CCS-projects as well as programmes to fund storage and grid strengthening (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2022a). However, the CAT does not see a role for CCS in the power sector, given its high cost, low technological maturity and residual emissions (Climate Action Tracker, 2023b).

Hydrogen

Canada released its Hydrogen Strategy in 2020 (Natural Resources Canada, 2020). It sees the shift to hydrogen as a key contributor in meeting both its 2030 NDC and net zero goals. The Strategy estimates that Canada could reduce emissions by 22–45 MtCO2e by 2030, representing 15% of total reductions, by supplying 6% of final demand, primarily in the transport and industry sectors. By 2050 it foresees savings of 90–190 MtCO2e through the use of hydrogen representing 26% of total reductions, by supplying 30% of final demand. The Strategy is not limited to green hydrogen (produced with renewable energy only), but includes hydrogen produced from fossil fuels with CCUS.

In contrast, Canada’s latest climate plan only includes a 15 MtCO2e reduction from hydrogen use by 2030. As much of the hydrogen would be produced using fossil gas, an additional 30 MtCO2e of CCUS capacity would be needed to capture the associated emissions (Office of the Auditor General of Canada, 2022b). For comparison, Canada’s only commercial CCS abated coal-fired power plant in operation was designed to capture 1 MtCO2e and has not yet achieved this target (see above for details).

Canada’s Commissioner for the Environment and Sustainable Development has heavily criticised the estimates in the Hydrogen Strategy, finding the underlying assumptions on policy implementation and price development ‘unrealistic’ (Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, 2022b; Office of the Auditor General of Canada, 2022b). One example is the assumption that a blending level of 7.3% can be achieved in the medium term: In the absence of blending obligations for 2030 a carbon price of at least CAD 500/tCO2, rather than the anticipated CAD 170/tCO2, would be required to achieve this.

Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine has reinforced the need for securing green hydrogen production and supply. In August 2022, Canada and Germany established a Hydrogen Alliance through which Canada would aim to start exporting hydrogen to Germany in 2025 (Government of Canada & Government of the Federal Republic of Germany, 2022).

Agriculture

Agriculture was responsible for around 8% of Canada’s total emissions in 2022 (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2024). The sector is projected to contribute around 4% of the emissions reductions in its latest 2030 climate plan. While the sector is responsible for 27% of the country’s methane emissions, it will contribute only about 1% of the reductions under Canada’s methane plan. Policy action is a mix of cross-cutting measures, individual targets and programmes and funding initiatives.

In 2020 Canada announced a voluntary target of reducing emissions from fertiliser use by 30% below 2020 levels by 2030, a key source of N2O emissions (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2020a). Direct emissions from synthetic nitrogen fertiliser have increased substantially since 2005. The government concluded consultations on the approaches to achieve the target in August 2022, but has not yet announced the next steps (Government of Canada, 2022c, 2022m, 2022n).

Some agricultural activities will be eligible for the federal government’s GHG offset system, established in June 2022. Credits generated under the system can be used to reduce the compliance costs of industrial facilities covered by the government’s carbon pricing system (OBPS). Protocols for projects related to livestock feed management and enhancing soil organic carbon are currently being developed and ones for manure management and anaerobic digestions are planned (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2022d; Government of Canada, 2022c).

Health Canada for the first time did not include a meat category, instead choosing to focus on “protein foods” (Government of Canada, 2019a; Health Canada, 2019). It also recommends choosing plant-based protein more often than other sources. Reducing emissions from agriculture, including through shifting the system to a more plant-based diet, will be key to meeting the Paris Agreement’s temperature goal.

Waste

Waste sector emissions accounted for around 3% of Canada’s total emissions in 2022, but 18% of the country’s methane emissions (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2024). Municipal landfills are the primary source of emissions. Efforts to reduce methane emissions to date have only been able to balance out the increased waste generated from a growing population and thus current methane levels from landfills are at about the same level as 20 years ago (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2022d).

Canada anticipates cutting methane emissions from the waste sector by 45% between 2020 and 2030 (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2022d). The government issued draft new regulations for consultation in 2023; final regulations are expected in 2024 (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2022b; Government of Canada, 2023d).

In June 2022, the government finalised the details around generating offset credits from landfill methane recovery and destruction projects (Government of Canada, 2022j). These credits can be used to reduce the compliance costs of industrial facilities covered by the government’s carbon pricing system (OBPS).

The Food Waste Reduction Challenge (discussed in the agriculture section) will also contribute to avoiding emissions in the sector.

Forestry

Canada’s vast forests have historically been both a source and a sink of emissions, officially contributing a small source in recent years. However, forest fires, and other disturbances like insect outbreaks, are not included in Canada’s forestry accounting. If these disturbances had been considered in 2018, for example, they would have added another 200 MtCO2e to Canada’s emissions, more than a quarter of the country’s reported total (Office of the Auditor General of Canada, 2023). Forest fires are intensifying across the country, with 2023 setting a tragic record: 16.5 Mha of land were burnt, an area larger than the country of Greece and over double the previous record from 1989 (Natural Resources Canada, 2023a).

Canada’s net zero strategy assumes a 100 MtCO2e sink in 2050 to assist with achieving the country’s net zero target (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2022c). According to its most recent inventory of 2024, Canada’s forests have never been a net sink. Canada will need significantly more action in this sector if it is to achieve such a large sink.

Two Billion Trees

Canada has a number of initiatives to support nature-based solutions (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2020a, 2022a). Its flagship plan, finally launched in 2021, is to plant two billion trees during the 2020s (Government of Canada, 2021a; Liberal Party of Canada, 2019; Natural Resources Canada, 2021c).

In April 2023, the country’s Auditor General expressed concern over the slow rollout of the plan, concluding that the two billion target would not be met without significant changes (Office of the Auditor General of Canada, 2023). The government contends that it is now back on-track (Natural Resources Canada, 2023e), yet the programme’s website still lacks basic tree planting information (how many planned versus actually planted) or any information about GHG sequestration.

The programme was designed to sequester up to 2 MtCO2e by 2030 and up to 11–12 MtCO2e by 2050, but the auditors concluded that it will be a tiny net source of emissions (0.1 MtCO2e) to 2030, due to emissions from planting activities and site preparation, and only sequester 4.3 MtCO2e in 2050 (Office of the Auditor General of Canada, 2023). Even if achieved, these emission reductions may be at least partially cancelled out by emissions from forest fires, given that several projects under the programme are used to reforest areas lost to recent wildfires (Natural Resources Canada, 2023c).

For context, Canada intends to rely on 12 MtCO2e of sequestration towards in 2030 in its base case, which includes this programme, and up to 27 MtCO2e with additional programmes.

GHG Offset System

Afforestation projects are not yet eligible to register credits under the federal GHG Offset system, but the government has considered allowing this in future (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2020b; Government of Canada, 2021f). If projects under the two billion trees initiative were eligible, this could open the door to double-counting of emissions reductions across the two systems.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter