Policies & action

Policies and action rating

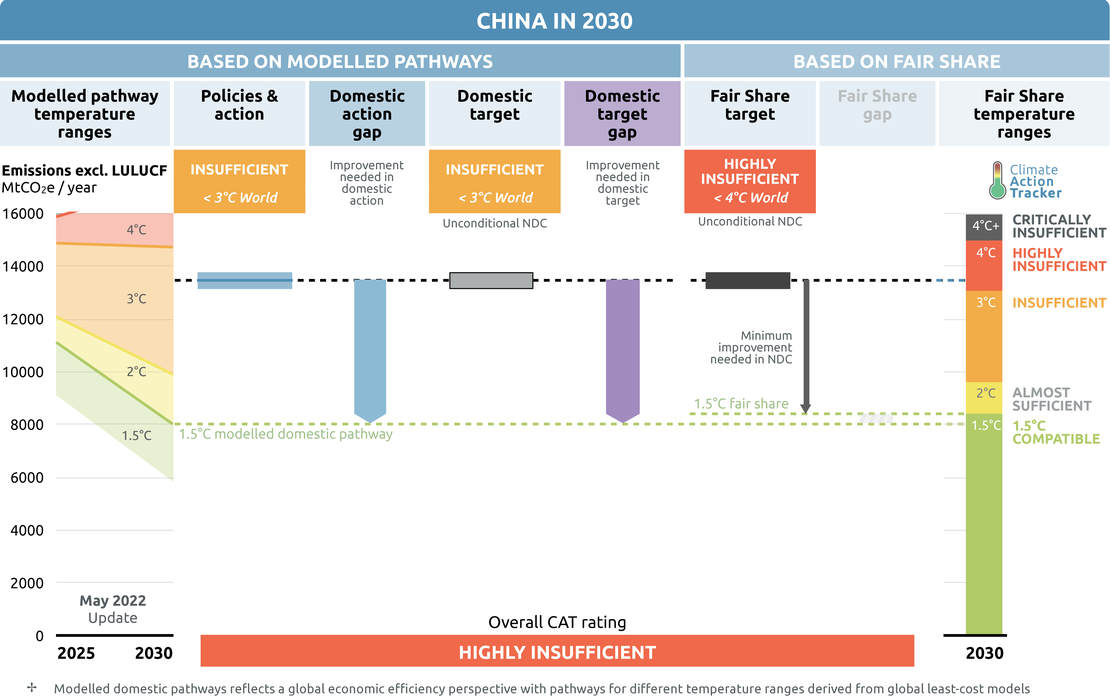

According to our analysis, China is likely to overachieve its energy-related NDC targets under its current policies projections as well as its carbon intensity NDC target. After revising our projections to incorporate the latest policy developments and analysis, we project GHG emissions levels of 13.2 to 13.8 GtCO2e in 2030.

The CAT rates China’s policies and action as “Insufficient” as current policy projections closely match China’s modelled domestic pathways consistent with global warming of over 2°C and up to 3°C by the end of the century (if all countries had this level of ambition). The “Insufficient” rating indicates that China’s climate policies and action in 2030 need substantial improvements to be consistent with the 1.5°C temperature limit. China is expected to implement additional policies with its own resources but will also need international support to implement policies in line with full decarbonisation. Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against modelled domestic pathways and fair share) can be found here.

Policy Overview (Summary)

China’s policy projections (including COVID-19 impacts) have been updated to reach GHG emissions levels (excl. LULUCF) of between 13.2 to 13.8 GtCO2e/yr in 2030, representing an increase in total GHG emissions of 262% to 278% above 1990 levels. The projections suggest China is likely to comfortably achieve its updated NDC targets, despite possibly increasing emissions in the short-term. Our current policies scenario, which incorporate China’s latest policies and guidance as well as technological trends, show that growth in non-fossil energy will surpass the country’s official NDC targets.

The CAT estimates China’s 2021 emissions at 14.1 GtCO2e, with the 2020 estimate revised down to 13.6 GtCO2e from 13.8 due to updated data. The COVID-19 pandemic initially led to a lockdown of economic activity in China in 2020, with carbon-intensive sectors heavily affected, but rebounded with surges in carbon-intensive construction and heavy industry activity.

In the second half of 2020, coal consumption rose by 3.2%, oil consumption by 6.5%, and gas consumption by 8.4%. Cement and steel production rose by 8.4 and 12.6% respectively, leading to an increase in energy consumption of 2.2% (Myllyvirta, 2021; Reuters, 2021). Emissions in 2021 grew even faster (by 3.4% compared to 1.7% from 2019–2020), due to a 10% increase in electricity demand—a growth of 750 TWh—mainly powered by coal (IEA, 2022b, 2022a).

Power consumption in China is again expected to increase by 5% to 6% in 2022, with the country forecasting an additional installation of 30 GW from coal-fired power plants by the end of the year to a total of 1140 GW, and an additional 180 GW by 2030 (from 2020 levels) (CEC, 2021).

In April 2021, President Xi Jinping announced at the Leaders’ Climate Summit that China will “strictly control coal consumption” over the next 14th Five-year Plan (14th FYP) period (2021–2025) and “phase down coal consumption” over the 15th FYP period (2026–2030) (Xinhua, 2021a). China also submitted its NDC and LTS ahead of COP26 with implications for declining coal consumption.

However, China’s outlook on coal appeared to have reversed by the end of 2021, as coal output rose to 4.13 billion tonnes (up 5.7% from 2020) over the year—China’s highest total ever (China Energy News, 2022; National Bureau of Statistics, 2022). Coal consumption subsequently also grew by 4.6% in 2021.

Growing reliance on coal, as well as oil and gas, is a result of increased energy security concerns over the past year. Ensuring a stable supply of fossil fuels has been a key strategic priority since China’s power shortage in 2021, and received significant focus in both China’s 14th FYP on energy (first circulated in January 2022) and “Two Sessions” government plenary meeting in 2022 (Global Times, 2022; NDRC and NEA, 2022). Many headline targets in the 14th FYP on energy focused on guaranteeing production capacity of fossil fuels, rather than capping their use.

Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine is likely to have exacerbated China’s concerns on energy security and thus prompt the country to increase its reliance on fossil fuels, accelerate deployment of renewables and other energy sources, and expand import channels (Bloomberg News, 2022). Prior to the war, China was a significant importer of fossil fuels from Russia, accounting for 20% and 25% of Russia’s exported oil and coal respectively (EIA, 2022; IEA, 2022c). China also imported 16.5 billion m3 of natural gas from Russia in 2021 and has since made plans to increase imports in the next decade by 25% with new oil and gas contracts worth $117.5 billion (Chen, 2022; Soldatkin and Chen, 2022).

While China is positioned to continue its strategic energy cooperation with Russia, which has been stockpiling yuan reserves and has already offered China discounted prices on oil, it is uncertain whether China will risk incurring economic sanctions placed by western countries on doing business with Russia; already, some Chinese banks have shied away doing so (Bochkov, 2022; Lo, 2022). Another strategy for China would be to expand its fossil fuel importing channels from non-Russian sources; while the 14th FYP on energy was drafted prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it clearly outlines a strategy to consolidate and expand cooperation with key oil and gas producing countries in the Belt and Road (NDRC and NEA, 2022).

Despite a growth in coal capacity, renewable energy (RE) continues to be a national priority and is expected to go beyond the updated non-fossil share (25% by 2030) and renewable capacity (1,200 GW by 2030) NDC targets. Installed RE capacity surpassed 1,000 GW in 2021 according to the government, showing an exponential trajectory from the approximately 250 GW installed in 2010 and 500 GW installed in 2015 (National Bureau of Statistics, 2022; Xinhua, 2022a). Both wind and solar exceeded 300 GW in 2021, and the CEC forecasts an additional 140–150 GW in wind and solar capacity to be added over the course of 2022 (CEC, 2022).

In 2021, the National Energy Administration (NEA) set a further target for renewables to make up half of the country’s installed capacity by 2025 (SASAC, 2021). China’s 14th FYP on energy, published in 2022, includes a target to raise the non-fossil share of electricity generation to around 39% in 2025. China’s Energy Supply and Consumption Revolution Strategy (2016–2030) has the additional target of a 50% non-fossil share of electricity generation in 2030.

The outlook on China’s 15% gas target in primary energy supply in 2030 has received a downward outlook to 12% projected by the China National Petroleum Corporation (Chow and Singh, 2021).

Industry subsectors are critical to achieving China’s new climate targets, and the steel, cement, and aluminium sectors are reportedly the first of seven sectors targeted in the expansion of the country’s national emissions trading system (ETS) (Wang, 2021; Wulandari, 2022). China's aluminium sector had initially targeted a peak in carbon emissions by 2025 (and to reduce emissions from that peak by 40% in 2040), with steel targeting a peak in 2025 (and to reduce CO2 by 30% from the peak in 2030), and cement targeting a peak in 2023. However, the discussed targets have not been officially adopted, while the carbon peaking date for the steel sector has been delayed to 2030 (Y. Wang, 2022).

In the transport sector, rapid uptake of electric vehicles (EVs) has continued with 7.8 million new energy vehicles (NEV) in 2021, of which 82% are battery EVs (Zhang, 2022). China’s NEV market share is reportedly on track to reach its 2025 20% target in the next year, reaching this market share target years in advance (Xinhua, 2020; Ren, 2022). China’s LTS stipulates that 40% of new vehicles sold by 2030 should be NEVs, with authorities suggesting a target of 50% NEV/50% hybrid new vehicle sales target by 2035 (Tabeta, 2020; Government of China, 2021).

In 2021, China launched its Emissions Trading Scheme, which covers 2,200 companies in the power sector (coal and gas plants) (ICAP, 2021). The ETS covers approximately 4.5 GtCO2/year and had a transaction volume of carbon emission allowances totalling approximately 179 Mt in 2021 (over 114 trading days) (Tan, 2022). The policy instrument aims to encourage further improvements in the CO2 emissions-intensity of coal plants, as well as earlier retirement for a young coal-fired power plant fleet.

Studies suggest that in its current form the scheme’s ability to reduce national emissions remains limited, but it could be an effective tool if benchmarks were tightened over time (Gray, 2021; IEA, 2021c). China’s emissions intensity benchmark for the power sector is expected to decrease around 8% from its 2019–2020 allocation level in 2022 (PV Europe, 2022). The ETS will expand to seven other sectors in the future (IEA, 2020a).

China’s strategy under its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which involves 126 countries that could account for as much as 66% of global carbon emissions in 2050, is shifting away from coal as the government pledged to end financing for building coal plants overseas (Jun et al., 2019; Carbon Brief, 2021). In July before the announcement, 56% of the global coal pipeline had been supported by China (Nicholas, 2021). Over 2021, China’s two global policy banks provided no new energy finance commitments to international governments for the first time since 2000 (Springer, 2022). The pledge could result in the cancellation of 43 GW of new coal projects across Asia, including no new coal projects in countries such as Bangladesh and Sri Lanka (CREA and Global Energy Monitor, 2021). However, the interpretation and execution of the pledge remains uncertain as new coal plants are being reportedly built in Indonesia with support from Chinese companies (Panda Paw Dragon Claw, 2022).

Glasgow sectoral initiatives

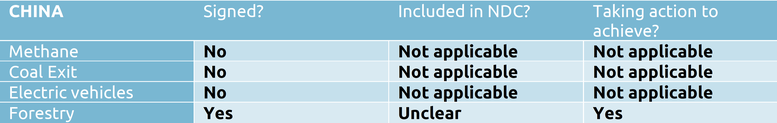

Four sectoral initiatives were launched in Glasgow to accelerate climate action on methane, the coal exit, 100% EVs and forests. At the time, the CAT estimated these initiatives would close the 2030 emissions gap by around 9% — or 2.2 GtCO2e, though assessing what is new and what is already covered by existing NDC targets is challenging.

The Global Methane Pledge seeks to cut emissions of methane gas in all sectors by 30% globally over the next decade. The Global Coal to Clean Power Transition initiative seeks to transition away from unabated coal power by the 2030s or 2040s and to cease building new coal plants, though some countries who joined did not agree to all measures.

Signatories of the 100% EVs declaration agreed that 100% of new car and van sales in 2040 should be electric vehicles, 2035 for leading markets. These targets are in line with the CAT’s Paris Agreement compatible benchmark for passenger transport to reach at least a 75% EV market share in by 2030, and 100% globally by 2040. Under the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forest and Land use, leaders agreed “to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030”.

Countries should update their NDCs to include any sectoral initiatives that are not covered by existing NDC targets. As with all targets, implementation of the necessary policies and measures is critical to ensuring that these sectoral objectives are actually achieved.

- Methane pledge: China did not adopt the methane pledge. Methane is a significant source of GHGs emissions in the country—surpassing 1.4 GtCO2e/year since 2020 according to our estimates—split between the energy (~47%), agriculture (~39%) and waste (~14%) sectors.

China’s updated NDC does not have explicit reduction targets for non-CO2 gases, though Measure 13 outlines their goal to accelerate control of these gases and phase out HFC gases under the Kigali Amendment.

The methane pledge unveiled at COP26 was received cautiously from China, with national experts citing different national circumstances and political gaming as potential reasons for not joining. However, China has continued its intention to tackle methane emissions, as evidenced both by its 14th Five-Year-Plan outline and the “U.S.-China Joint Glasgow Declaration on Enhancing Climate Action” during COP26, where the two largest global emitters stated their intent to cooperate to control and reduce methane emissions and China stated its intent to “develop a comprehensive and ambitious National Action Plan on methane, aiming to achieve a significant effect on methane emissions control and reductions in the 2020s”. If China were to sign up to and implement the pledge, we calculate that it would reduce methane emissions by 420 MtCO2e/year in 2030.

- Coal exit: China has not adopted the coal exit, though it is the largest consumer and builder of the fossil fuel. China is forecast to have 1140 GW of coal-fired power plants installed by the end of 2022, more than half of the world’s installed capacity. The country is committed to decrease its reliance on coal (and fossil fuels in general) in its NDC and has signalled a peaking of coal consumption by 2025. However, China still has over 200 GW of domestic coal-fired power plants in the pipeline in 2022.

Although the peak of China’s coal capacity and consumption is uncertain in its NDC and other high-level medium-term policies, building (and utilising) additional coal capacity will make it more difficult to achieve its NDC’s non-fossil energy targets and long-term carbon neutrality targets. For more detail on coal developments, see the section on Energy Supply below.

- 100% EVs: China did not adopt the EV target during COP26. Transport emissions are substantial in China, with an estimated 750 MtCO2e/year coming from passenger cars alone in 2022.

Decarbonising transport is not explicitly part of China’s NDC commitments, although its energy and emission peak targets have implications for transport emissions. While China did not sign up to the initiative, the country’s LTS notes that its domestic EV sales share will reach an equally ambitious trajectory of 40% by 2030 (Government of China, 2021). For more details on transport sector emissions, refer to the Transport section below.

If China was to reach 100% zero emission vehicle sales by 2035, it would reduce emissions by 50 to 90 MtCO2e/year in 2030 depending on the carbon intensity of electricity.

- Forestry: China signed the forestry pledge at COP26 on November 2, 2021, committing to end deforestation by 2030. While such a commitment is not part of China’s NDC, the document contains a target to increase the forest stock volume by 6 billion cubic meters from the 2005 level. For more details on China’s forestry policy developments, see the Forestry section below.

Energy Supply

Controlling coal and fossil-fuel consumption

China is making another reversal in its coal strategy and outlook by doubling down on the fossil fuel for energy security. This shift came amidst China’s concerns over its power shortages in 2021 and led to the highest annual coal output by year end, at 4.13 billion tonnes (up 5.7% from 2020) according to the National Bureau of Statistics. China’s coal consumption in 2021 also grew to 2.93 billion tonnes of coal equivalent, up 4.6% from 2020 and made up 56% of the nation’s energy consumption (National Bureau of Statistics, 2022). Coal capacity grew by 25 GW in 2021, where for the fourth year in a row, the global coal fleet outside the country shrank (Global Energy Monitor et al., 2022).

In 2021, China’s long-term dependence on coal was seemingly weakened when President Xi Jinping announced at the Leaders Climate Summit that China will “strictly control coal consumption” over the next 14th FYP period (2021–2025) and to “phase down coal consumption” over the 15th FYP (2026–2030) (Xinhua, 2021a).

In the leadup to the announcement, moving away from coal had seemingly become a political priority as the Central Environmental Inspection Team (CEIT) publicly criticised the National Energy Administration (NEA) for negligent coal planning and regulation and treatment of energy security (i.e., coal) as the nation’s top priority (while falling behind in low-carbon energy growth) (Lo, 2020). Malpractice in the coal industry was also heavily targeted, with a growing list of people investigated and arrested for corruption (Xinhua, 2021b; Zheng, 2021).

However, recent developments suggest coal will continue to play a core and possibly increasing role in energy supply for the foreseeable future. While “in principle”, the country supposedly will not build any more coal-fired power projects (whose sole purpose is to generate electricity) it clarifies that it will continue to build coal-fired power plants under two exceptions: to provide energy security and to support flexible peaking services under further development of renewable energy (China Energy News, 2022).

China’s response to its well-documented power shortage in 2021—caused by a mix of high energy demand pressure and low coal supplies—has led to a resurgence and re-emphasis of coal as a source to shore up energy security. China’s post-pandemic recovery led to almost 750 TWh of increased electricity demand in 2021 compared to 2020, half of the world’s year-on-year energy demand increase. The domestic coal supply had been insufficient due to disruptions in imports from Indonesia and Australia, anti-corruption investigations in Inner Mongolia, increased demand from recovery activities (+11% in first half of 2021), and rising coal prices that delayed restocking of supplies (Meidan and Andrews-Speed, 2021; IEA, 2022a).

In response, China introduced new coal-friendly policies to counter the shortage, including opening new mines, stabilising coal prices and raising coal cap prices, and increasing production targets (Global Times, 2021; NDRC, 2021; Xinhuanet, 2021). Power consumption in China is again expected to increase by 5–6% in 2022, with the China Electricity Council (CEC) forecasting an additional installation of 30 GW from coal-fired power plants by the end of the year. Between 2020–2025, the CEC expects China to add 150 GW new coal capacity, with an additional 30 GW before 2030 (CEC, 2021).

However, as China eventually decreases its dependence on coal power and oil—the latter which it has pledged to peak and plateau before 2030—it is likely to compensate with increased consumption of natural gas rather than with clean energy sources, given the country’s energy demand is also rising.

Just weeks before Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine, China and Russia agreed long-term significant oil and gas contracts (for up to 30 years) to increase imports into China (Chen, 2022). China has now overtaken Japan to become the world’s largest liquified-natural-gas importer and is building 90 GW of new gas plants to satisfy heating and power needs in the future. The country plans to extend its gas pipeline infrastructure by 40%, which would double its LNG import capacity (Rozansky and Shearer, 2021; Caixin, 2022).

These developments could potentially lead to stranded assets in the order of USD 89bn (Langenbrunner, Joly and Aitken, 2022). While China’s Energy Supply and Consumption Revolution Strategy (2016–2030) targets a 15% share of gas in its energy mix by 2030, the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) expects gas to satisfy only 12% by 2030 (Asia Pacific Energy, no date; Chow and Singh, 2021).

China’s increased coal consumption and development in the last five years has been inconsistent with the Paris Agreement and is contrary to the declining global trends since 2018. Although China has cancelled 484 GW of its coal pipeline since Paris, it still accounted for half of the world’s coal-fired generation and coal-fired power plant pre-construction pipeline in 2020 (Ember, 2020; E3G, 2021).

Politically, over the last decade the narrative around coal has been a back-and-forth affair. Controlling and decreasing coal consumption has been China’s explicit policy objective since the development of its National Action Plan on Climate Change (2014–2020), while the 13th Five Year Plan (FYP) period (2016–2020) introduced a slew of coal-related targets, such as a ban on new coal-fired power plants (lifted in 2018), and a cap of 1,100 GW of installed coal capacity. Much hope was placed on 2021’s 14th FYP to put more stringent regulation on coal development.

While forthcoming power sector and climate change FYPs may shed more light, the first outline suggests that China will remain dependent on the dirtiest of fossil fuels in the next planning period for energy security reasons, a theme stretching across previous decades (Kemp, 2021).

To be compatible with a 1.5°C pathway, China would need to decrease the share of unabated coal in power generation to at least 35% in 2030, with a complete phase-out before 2040 (Climate Action Tracker, 2021a). China’s coal share of power generation was 64% in 2020, making it one of the most coal-reliant power sectors out of the world’s biggest emitters (see graph below).

To reach China’s long-term carbon-neutrality target by 2060, the country must retire nearly 600 of its coal-fired power plants in the next 10 years, according to Transition Zero (Gray, 2021). Another study suggests that if China were to follow-through with its coal capacity addition plans (~200 GW), its stranded asset costs could increase by 2.7x to approximately USD 150bn (W. Zhang et al., 2021).

Renewable and non-fossil energy growth

China’s growth in renewable energy (RE) capacity installations have not slowed, despite parallel increases in fossil fuel capacity. RE capacity surpassed 1,000 GW in 2021, showing an exponential trajectory from the approximately 250 GW installed by 2010 and 500 GW installed by 2015 (National Bureau of Statistics, 2022; Xinhua, 2022a). Both wind and solar exceeded 300 GW each in 2021, with hydropower still representing the largest single source of renewable capacity. The CEC forecasts an additional 140–150 GW in wind and solar capacity to be added over the course of 2022 (CEC, 2022).

For 2020, China had set targets for non-fossil capacity installed—340 GW of hydropower, 200 GW of wind power, 15 GW from biomass, 120 GW of solar power—and comfortably overachieved them (by two-fold in the case of solar) with the exception of nuclear, according to our analysis. China updated its RE targets in its NDC in 2021 to increase the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to “around 25%” in 2030, (up from “around 20%”), and increase the installed capacity of wind and solar power to 1,200 GW by 2030. The 14th FYP also set an interim target in the NDC with a 20% non-fossil share target in 2025.

The National Energy Administration (NEA) in 2021 also set a target for renewables to make up half of the country’s installed capacity by 2025, which has since been confirmed in guidance to state-owned enterprises (SASAC, 2021). Under these strategic visions, we expect combined solar and wind capacity to exceed 800 GW in 2025 alone, with hydro exceeding 400 GW. Our analysis estimates non-fossil energy sources to account for 23% to 26% of China’s total primary energy demand in 2025 and 30% to 32% in 2030.

If China’s trend of RE installations continue at the expected rate, the country will easily achieve its NDC target for solar and wind installation. According to the Energy Research Institute, an affiliate of the National Development and Reform Commission, China’s pathway to achieve its 2060 carbon neutrality target would result in 1,650 GW of wind and solar in 2030 (due to forecasted economic competitiveness of the technologies coupled with China’s 2030 CO2 peaking target)—450 GW more than the country committed in its NDC RE installation pledge (ERI, 2021). In our projections, China approximately reaches this figure in 2030, suggesting its rate of renewable installations are on track to reach the 2060 target. The Ministry of Ecology and Environment expects half of China’s energy consumption in 2045 to be satisfied with RE, with the figure rising to 68% in 2060 (nuclear expected to rise to 13%).

To be compatible with a 1.5°C pathway, China would need to have shares of renewable electricity generation reach at least 75% in 2030, although China is not on course to reach that mark. Compared with the other two largest emitters, China has faster projected growth in renewables. Globally, all countries will need to have 98–100% renewable electricity shares by 2050 to be 1.5°C-compatible.

Industry

Industry is the largest energy consuming sector in China, accounting for about 59% of the country’s final consumption in 2020. Between 2020–30, energy demand from this sector is expected to increase another 14%.

Half of the direct energy consumed in the sector currently comes from unabated coal—representing about 70% of China’s total coal consumption—although use of the fuel is expected to plateau in the next decade (IEA, 2021d). Some government researchers suggest that coal use in steel and cement sectors should have peaked in early 2020s (Xu and Singh, 2021). Use of electricity and natural gas in industry has increased by 70% and doubled since 2010 (IEA, 2021a).

Steel and cement output from real estate and infrastructure construction, which had been largely responsible for growing industry emissions in the lead up to the global pandemic in 2020, was boosted when the post pandemic stimulus response targeted infrastructure construction. While subsectors such as cement and oil product production dropped significantly in the first months of 2020, the second half of the year showed cement production reversing its trend, increasing by 8.4%, while steel production increased by 12.6%. China’s CO2 emissions subsequently surged 4% over the same period (Myllyvirta, 2021).

In 2021, China produced just over 1.1 billion tonnes of crude steel, a 2.8% decrease compared to 2020 (National Bureau of Statistics, 2022). While China’s domestic steel demand is expected to peak in the coming years, global appetite for steel is likely to increase in developing regions such as ASEAN, Africa, and India (IEA, 2021b).

Given the Chinese industry’s gargantuan energy consumption, the decarbonisation of industry subsectors is critical—and central—to achieving national climate and energy targets. Key emitting sectors, such as steel, aluminum, and cement, had seemingly been rising to the challenge and aligning expectations with the 14th FYP and NDC update. The three sub-sectors are likely to be the first targeted in the scope expansion of the country’s ETS (Wang, 2021; Wulandari, 2022).

The cement sector discussed an emissions peak in 2023, in line with calls from the China Building Materials Federation as well as independent estimates from a group consisting of the Chinese Academy of Environmental Planning, a public institution (Schmidt, 2022).

The iron and steel sector initially targeted a peak in 2025 with aims to reduce its carbon emissions by 30% from the peak by 2030, while the China Nonferrous Metals Industry Association reported a possible extended target of a 40% reduction by 2040 (Finance Sina, 2021b; Hu and Ng, 2021). In the draft version of the ‘Nonferrous Metals Industry Carbon Peak Action Plan’, China’s aluminum sector was set to target a peak in carbon emissions by 2025 (although analysts claim this may be sooner), and to reduce emissions from that peak by 40% in 2040 (Bloomberg, 2021; EEO, 2021). However, the discussed targets have not been officially adopted.

A carbon peaking date for the steel sector was delayed to 2030 in its new high-level guidance (from 2025 in the consultation version) (Y. Wang, 2022). The five-year delay in steel sector peaking could be to allow the sector breathing room amidst energy and supply chain security concerns and to consolidate a less ambitious target that could be reached by all steel companies (rather than as a sector) in a bid to tackle other industry concerns such as overcapacity and pollution (Guoping and Zou, 2022; Lin, 2022).

It remains unclear how these targets will affect China’s New Infrastructure Plan, the country’s strategic goal to transition its industrial sector towards research and development and technological innovation, as the initiative creates a heavy need for construction materials. China is also set to release the China Standards 2035 plan, which aims to use the technological advantage gained in Made in China 2025 to set domestic – and eventually global – industry standards for next-generation technologies such as 5G, the Internet of Things (IoT), and artificial intelligence (Koty, 2020).

To decarbonise China’s hard-to-abate sectors, development of CCS/CCUS and hydrogen solutions have become priority strategy areas for Chinese industry. CCUS will be a critical technology to help China drastically reduce emissions towards carbon neutrality in the long-term and has received increasing national attention in the last two decades, with objectives now focusing mainly on large-scale project demonstrations.

As of 2021, CCUS was highlighted in the last three FYPs, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) have encouraged provinces have been encouraged to pilot and demonstrate CCUS projects, and 29 provinces had already issued policies and plans related to the technology. Since the 10th FYP (2000–2005), China has invested more than 3bn yuan into CCUS R&D (Fan, 2021).

China, the world’s largest producer of hydrogen, published its national hydrogen strategy (2021–2035) in 2022, confirming the technology’s key role in China’s future energy system and mitigation efforts. While hydrogen is mainly produced from coal and gas sources, the plan targets a modest production of 100,000–200,000 tonnes of “green” hydrogen with renewable sources by 2025 (Yao, 2022). Given China’s hydrogen production reached 25 million tonnes in 2022, this would constitute less than 1% of its production. The China Hydrogen Alliance estimates this could reach 100 Mt by 2060, accounting for 20 percent of the country’s final energy consumption (Nakano, 2022).

China has further been active in tackling non-CO2 emissions, most notably in regulating hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) emissions from refrigeration and cooling activities embedded in many industrial activities. China produces – and consumes – more than 60% of the world’s HFCs. China’s first NDC committed to targeted reductions of HCFC22 production of 35% by 2020 and 67.5% by 2025 below 2010 levels, but there are no numerical targets in its updated NDC.

In US-China bilateral climate discussions in 2021, both countries recommitted to implement the phasedown of HFC production and consumption, reflected in the Kigali Amendment, a commitment also re-emphasised in a bilateral agreement between French President Macron and President Xi in 2019 (IGSD, 2019; US DOS, 2021). China finally ratified and started enforcing the Kigali Amendment in 2022 (Rudd, 2021).

China reported that it halted new production capacity of five of the 11 HFCs it produces (covering 75% of total HFC production) two years ahead of the freeze requirements of the Amendment (McKenna, 2022). According to our analysis, under the Kigali Amendment’s phase out schedule, China would reduce emissions by a modest ~40 MtCO2e/year by 2030, although emission reductions could increase to almost 400 MtCO2e/year by 2045. A 2019 estimate that a full phaseout of all HFC gases could reduce China’s emissions by more than 650 MtCO2e/yr in 2050 compared to current policies at the time (Lin et al., 2019).

Transport

China’s transport sector is a vast consumer of energy (trailing only the industry sector) and accounts for almost 14% of national primary energy consumption (IEA, 2021d). Urban passenger transport is the primary end-use sub-sector, with activity having increased ten-fold from 2005 to 2019 (Energy Foundation China, 2020). Road transport, and specifically gasoline passenger cars, has been the largest source of emissions.

China’s prioritisation of new energy vehicle (NEV) uptake, including battery electric vehicles (BEVs), plug-in hybrid vehicles (PHEVs), and fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs), has been documented as far back as the 1990s. The growth in NEV sales faltered briefly before the onset of the global pandemic, as the government halved purchase subsidies in 2019 and cut them further in 2020, part of a phase-out of incentives due to end in 2020 (Sun and Goh, 2020; Vincent, 2020).

A massive slump in NEV (and all car) sales followed when the auto industry was hit even harder during COVID-19 (sales were down 80% in February 2020 compared to the same time in 2019) (BBC, 2020; IEA, 2020b). China subsequently targeted the NEV sector in its economic recovery packages, extending the subsidy scheme to 2022 and injecting CNY 2.7bn (USD 0.42bn) in BEV charging infrastructure (Cheng, 2020).

NEV car sales rebounded; by the end of 2020, of a total light duty vehicle fleet of 281 million, 4.9 million (1.7%) were NEVs, according to the Ministry of Public Security (Finance Sina, 2021a).

By the end of 2021, the China’s Ministry of Public Security reported that China’s NEV fleet had grown to a staggering 7.8 million (after considering scrapped vehicles), of which 82% are BEVs; this represents a YOY growth of almost 60% for BEVs while total light duty vehicles increased only 7.5% (to 302 million (Zhang, 2022).

China’s NEV market share is reportedly on track to reach its 20% target in the next year, reaching the 2025 market share target years in advance (Xinhua, 2020; Ren, 2022). China’s LTS stipulates that 40% of new vehicles sold by 2030 should be NEVs, with authorities suggesting a target of 50% NEV/50% hybrid sales target by 2035 (Tabeta, 2020; Government of China, 2021).

Due to accelerating market forces promoting NEV sales, the government appeared to confirm that the industry has already matured to be purely demand-driven, by reducing emphasis on policy support for NEVs in the latest 14th FYP (Shen, 2021). The Ministry of Finance has also continued the phase out schedule for NEVs subsidies with a 20% cut in 2021, a 30% cut in 2022, and a complete withdrawal by the end of the year (Sun and Goh, 2020). Recent research also suggests that the market is reaching maturity, as BEV initial price parity with conventional cars and sport utility vehicles is likely to be achieved within China in 5–10 years, without yet accounting for fuel savings (Lutsey, Cui and Yu, 2021).

In our 2021 scenario analysis of post-Covid NEV policies even the most ambitious scenario (modelling 100% BEV sales by 2035) would lead to a 70 to 110 MtCO₂e/year in emissions reductions from the reference scenario in 2030, with the figure rising to 370 to 850 MtCO2e/year in 2050 depending on the carbon intensity of electricity (which has been updated in 2022) (Climate Action Tracker, 2021b). According to a study by Greenpeace, to reach a net zero emissions car fleet by 2060, China’s fleet would need to decrease emissions by 20% from peaking levels and have NEV market shares of 63% in 2030 and 87% in 2035 (Greenpeace, 2022).

Despite modest implications in the medium-term, rapid EV deployment is a requirement for establishing a 1.5°C-compatible car industry. To limit global temperature increase to 1.5°C, China’s EV stock will need to make up 35% to 50% of the entire car fleet by 2040, when the last fossil fuel car will also need to be sold (Climate Action Tracker, 2020a). By 2040, China is only projected to reach a 70% EV market share (rather than 100%), although this is the most rapid trajectory of the world’s largest emitters.

China is also giving high prioritisation to other forms of electrified transport. It already boasts 80% of the world’s public fast chargers (particularly important for electric buses in urban travel) and has outlined expansion of national high-speed rail and local electric public transport systems in its COVID economic stimulus packages. China’s high speed rail network consisted of about 38,000 km in 2020 (all built since 2008) and is planned to extend to 50,000 km in 2025 and 70,000 km by 2035 (Jones, 2022; O. Wang, 2022).

The uptake of electric buses has been rapid, with approximately 84% of the world’s electric buses in 2030 expected to be operating in China (BloombergNEF, 2019; Eckhouse, 2019). More than 30 Chinese cities have announced plans to completely electrify their taxi and bus fleets by 2022 and municipalities involved in the EV Pilot Cities Programme, such as Shenzhen, virtually already reached these targets several years ago (UNEP, 2019). According to the IEA, 25% of the world’s electric two and three-wheelers in circulation (approximately 350 million) are in China (IEA, 2020b).

The transport sector currently accounts for 58% of oil consumption in China (NRDC, 2019). The increasing importance of electricity for inter and intra-city mobility in China decreases its dependence on oil in the long-term. China’s LTS states that oil consumption will peak and plateau during the 15th five-year plan period, from 2026 to 2030 (Government of China, 2021).

China manages its conventional petrol and diesel vehicles mostly through fuel economy standards and staged phase-out of inefficient vehicles. Previous fuel economy standards for passenger cars finished in 2020. For cars, the fuel economy standard will be upgraded to a fleet average target of 4L/100km in 2025 (previous standards targeted fleet average of 5L/100km in 2020) (IEA, 2020b).

Buildings

China’s LTS states that by 2025, all new buildings would adhere to China’s “green building standards” and have an 8% replacement of fossil fuel energy consumption by renewables. The country has on average constructed around 4 billion m2 of new floor space annually from 2013–2020 (National Bureau of Statistics, 2021). Further, China will “strive to” install solar panels on 50% of the rooftops on new public buildings and factories starting in 2025 (Government of China, 2021). Currently, fossil fuel sources supply a third of energy consumption in buildings and half of all space heating (IEA, 2021a). China has mandatory energy efficiency codes for urban residential and commercial buildings and promotes voluntary energy efficiency codes for rural residential buildings through financial incentives (GBPN, 2018). In 2018, more than 2.5 billion m2 of urban and commercial floor space was green-building certified, while China has also launched its Near Zero-emission Buildings Standard (NZEB) in 2019, which will provide the technical basis for decarbonization in building sector in China through 2060 (S. C. Zhang et al., 2021). By 2020, almost 10 million m2 of NZEB projects have either been in construction or completed (Zhang and Fu, 2021).

China’s 13th FYP included targets for improving building energy efficiency standards and retrofitting, including targets to achieve a 65% energy efficiency level compared to 1980 and retrofit 500 million m2 of existing residential floor space, and increase the total of green building floor space to 2 billion m2. The 13th FYP also targeted an increase of the renewable energy utilization rate in total building energy consumption to 6% (from 4% in 2015) (Zhou et al., 2020). Retrofits of buildings are paramount in China’s bid for energy efficiency in the sector, as the average age of building stock is young at 15 years, meaning almost half of existing floor space could still exist by 2050 (IEA, 2021a). It is unclear whether China’s 13th FYP targets have been achieved, and details are still pending on building sector targets in China’s 14th FYP.

For compatibility with the Paris Agreement temperature goals, China’s emissions-intensity in residential and commercial buildings needs to be reduced by at least 65% in 2030, 90% in 2040, and 95–100% in 2050 below 2015 levels, while energy intensity needs to be reduced by at least 20% in 2030, 35–40% in 2040, and 45–50% in 2050 compared to 2015 levels. China will also need to achieve renovation rates of 2.5% per year until 2030 and 3.5% until 2040 to achieve a Paris-compatible buildings sector by 2050 (Climate Action Tracker, 2020b).

Forestry

China’s updated NDC pledges to increase forest stock volume by 6 billion m3 by 2030 compared to 2005 levels (up from 4.5 billion m3). At COP26 China signed the Glasgow Declaration on Forest and Land Use, which is committed to “halt and reverse” forest loss and land degradation by 2030.

In 2021, China stated that it will plant 36,000 km2 of new forest annually to 2025 in a bid to increase the forest coverage to 24.1% (from 23.04% in 2020) (Stanway, 2021). China’s drive for implementing forestry projects has been extensive, but not without setbacks. Initiatives such as the Three-North Shelter Forest Programme aiming to grow 35 million hectares (a forest the size of Germany) in northern regions by 2050 has faced trial and error due to poor planning and management (Bloomberg, 2020).

China has implemented many national forest conservation policies, beginning with the National Forest Protection Programme, which aims to recover native forests, and which has more recently been expanded to ban commercial logging in native forests. In 2020, China revised its Forest Law for the first time in 20 years, with the most significant policy change being the implementation of a ban (in effect as of July 2020) on Chinese companies purchasing, processing, or transporting illegal logs (Client Earth, 2020; Mukpo, 2020).

China is both the world’s largest importer of legal and illegal logs, with a large portion of its tropical timber imports in 2018 coming from countries with weak governance and accountability indicators, according to reports (Global Witness, 2019). As illegal trade could represent up to 30% of trade in all wood products and be worth up to USD 150bn a year, the revised Forest Law could have a large impact on curbing global deforestation (Interpol, 2019; World Bank, 2019).

China has been a large proponent of nature-based solutions and was a co-lead of the nature-based solutions coalition for the Climate Action Summit in 2019, which received over 200 submissions for initiatives that could help preserve and sustainably manage global forests (IISD, 2019; Ministry of Ecology and Environment, 2019). China is still set to host the UN Biodiversity Conference in Kunming in August 2022, although this has been delayed four times. The deal to be negotiated in Kunming involves deliberation on the Post-2020 Biodiversity Framework, which targets to cover 30% of Earth’s land and seas as protected areas by 2030 (Vaughan, 2022).

To reach China’s carbon neutrality goal by 2060, carbon sequestration through afforestation or other means such as direct air capture, are assumed to play a critical role (He, 2020). However, for Paris Agreement compatibility, sinks from the forestry sector should not be used as an excuse to delay emissions reductions in other sectors (Climate Action Tracker, 2016).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter