Pledges And Targets

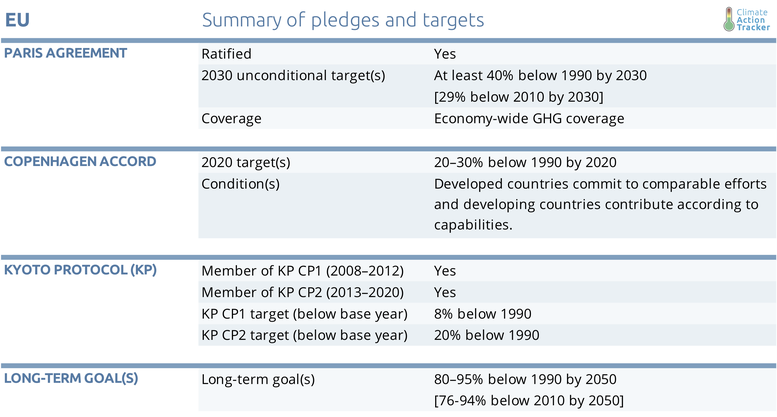

Summary table

Paris Agreement targets

In October 2014 EU leaders agreed on a 2030 climate and energy policy framework, putting forward a legally binding EU target of at least 40% reduction in domestic emissions by 2030 in comparison to 1990 (Council of the European Union 2014). In contrast to the period before 2020 it will also make no use of international credits, as it refers to domestic emissions reductions only. This target became the basis for the EU’s first NDC (European Council 2015).

Achievement of the renewable energy (32% share in final energy consumption as opposed to earlier 27%) and energy efficiency (32.5% improvement in comparison to business-as-usual, as opposed to earlier 27% suggested by the Council and 30% subsequently suggested by the Commission) goals agreed in June 2018 would result in greenhouse gas emissions reductions approaching 45% (European Commission 2018d; Terlouw, Blok, and Klessmann 2018). While this has not yet been reflected in an updated Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), in its position for COP24 the European Council pointed out that the more ambitious renewable energy and energy efficiency targets would have an impact on the level of emissions and that the EU and its member states would take stock of those additional efforts and other specific policies (Council of the European Union 2018a). The European Parliament—similarly to an earlier call by the Dutch government—has called for the adoption of a more ambitious emissions reduction target of 55% (European Parliament 2018d; Government of the Netherlands 2018).

A study by Climact and New Climate Institute shows that emissions reduction of up to 62% would be possible if best practice policies found in some EU member states are applied across the EU (Climact & New Climate Institute 2018).

The uncertainty around LULUCF accounting

Following the agreement reached between the European Parliament and the Council in December 2017, in June 2018, the Regulation dealing with the inclusion of emissions and removals from the LULUCF sector in the EU 2030 climate and energy framework entered into force. Combined with the Effort Sharing Regulation adopted in parallel it allows the utilisation of credits from removals from that sector of up to 280 MtCO2—spread over the period between 2021 and 2030—to meet the emissions reduction target in the non-ETS sectors (European Parliament and the Council of the European Union 2018e, 2018f). Since the removals have not been included in 1990 emissions levels, this means a potential weakening of the 2030 emissions reduction target. The best assumption that can be made about the utilisation of the 280 MtCO2 from the LULUCF sector is that, on average, all member states will use these allocations divided equally every year over the whole period between 2021 and 2030. This would potentially weaken the EU’s 2030 emissions reduction target by 28 MtCO2 or 0.8%.

2020 pledge and Kyoto target

Under the Copenhagen Accord, the EU committed to reducing emissions by 20% below 1990 levels. Should other developed countries commit to comparable efforts, and developing countries contribute according to their capabilities, the EU offered to increase its 2020 emissions reduction target to 30%.

In May 2012, the EU submitted a provisional QELRO1 (Quantified Emission Limitation or Reduction Objective) level equivalent to 20% reduction from base year over the second commitment period. This target is to be fulfilled jointly by the EU and its member states.2

In 2015 the EU and Iceland signed an agreement to jointly fulfil the second phase of the Kyoto Protocol (European Commission 2015a).

In 2008 the EU member states agreed on the 2020 Energy and Climate Package that included a number of measures that would make the achievement of the 20% emissions reduction target possible. These measures included the Effort Sharing Directive specifying national emissions targets for the EU member states, amendment of the EU’s Emissions Trading Scheme, and the Renewable Energy Directive aiming to increase the share of renewables to 20% by 2020. While the EU has already achieved the emissions reduction target for 2020, it is on track to achieving the latter one as well with 17% of energy in the EU coming from renewables in 2016 (Eurostat 2018b).

1 | The QELRO, expressed as a percentage in relation to a base year, denotes the average level of emissions that an Annex B Party could emit on an annual basis during a given commitment period.

2 | This QELRO is inscribed in the amendments agreed in Doha in December 2012. The EU has yet to ratify these amendments.

Long-term goal

In February 2011, based on the former 2°C warming limit agreed in Copenhagen, EU leaders endorsed the objective of reducing Europe's GHG emissions by 80–95% below 1990 levels by 2050 (European Commission 2011b) conditional on necessary reductions to be collectively achieved by developed countries in line with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). However, the Paris Agreement’s long-term temperature goal is significantly more ambitious than the former 2°C Copenhagen target, and requires more rapid—and deeper—emissions reductions.

In March 2018, the European Council invited the Commission to present a proposal for a Strategy for long-term EU greenhouse gas emissions reduction by the end of the first quarter of 2019. The member states pointed out that it should remain in accordance with the Paris Agreement and take into account the national plans. The political agreement on the draft of the Governance Regulation reached in June 2018 obliges the European Commission to, inter alia, develop a scenario on achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 and negative emissions thereafter. However, contrary to the initial position of the Parliament, it does not set a clear date when the EU should achieve carbon neutrality, instead stating that it should happen “as soon as possible” (Council of the European Union 2018b).

The European Parliament and the mayors of the ten largest European cities have already called for aiming for climate neutrality by the middle of the century (C40 Cities 2018; Euractiv 2018a). Such a goal also has support of some member states: in the Meseberg Declaration, the German Chancellor Angela Merkel and the French President Emmanuel Macron agreed to “develop an EU strategy 2050 for the long-term transformation towards carbon neutrality, which is not only a necessity, but also an economic opportunity” (The Federal Chancellor 2018). In their common statement adopted in June 2018 representatives of 14 EU member states—representing 76% of the EU population demanded that the long-term strategy includes “at least one pathway towards net zero GHG emissions in the EU by 2050 followed by negative emissions thereafter” (The Ministry for an Ecological and Solidary Transition 2018).

Some member states have already adopted - or are considering adopting—such a goal at a national level:

- In July 2017 the French government presented its climate plan with the aim of greenhouse gas emissions neutrality by 2050 (Ministry for the Ecological and Inclusive Transition 2017).

- In June 2018, all Danish political parties agreed to aim at carbon neutrality by 2050 (The Ministry of Energy Utilities and Climate 2018).

- Sweden’s January 2018 Climate Act introduced the goal of net-zero emissions by 2045 (Government Offices of Sweden 2018).

- In March 2018 Finnish Parliament approved the government’s report on a medium-term climate change policy plan for 2030, which also suggests adopting a target of carbon neutrality by 2045 (Ministry of the Environment 2018).

- In 2016 Portugal adopted the objective of achieving carbon neutrality by the end of the first half of this century. This target was reconfirmed by Portuguese Prime Minister António Costa during COP22 in Marrakech (REA 2018).

- The Climate Law adopted by the Dutch Parliament in June 2018 introduces the target of reducing GHG emissions by 95% by 2050 (Groenlinks 2018).

- The UK Minister of State for Energy and Clean Growth, Claire Perry, raised the possibility of the UK increasing its 2050 emissions reduction target from 80% to “net zero” (The Guardian 2018).

- Germany has adopted an objective of “extensive greenhouse gas neutrality by mid-century” with its Climate Action Plan 2050, (Federal MInistry for the Environmet Nature Conservationand Nuclear Safety 2018).

Adopting the target of climate neutrality at the European level would enhance the EU’s position as a leader in climate action. Such a role has been called for by Commission President, Jean-Claude Juncker, in his State of the Union Address in September 2017 and French President Emmanuel Macron’s speech two weeks later (European Commission 2017d; Ouest France 2017).

While so far only a few EU member states adopted or presented their long-term emissions strategies, the Governance Regulation obliges all EU countries to prepare and report their long-term strategies with a perspective of at least 30 years, before 1 January 2020 (Council of the European Union 2018b).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter