Policies & action

The CAT rates the EU’s current policies and actions against modelled domestic pathways as “Insufficient”. The “Insufficient” rating indicates that the EU’s climate policies and action in 2030 need substantial improvements to be consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C. If all countries were to follow the EU’s approach, warming would reach over 2°C and up to 3°C.

With its current policies in place, the EU’s emissions will reach between 2,470 and 2,755 MtCO2e (excluding LULUCF) in 2030. This current policies pathway does not set it on track to meet its existing 2030 NDC target of 2,307 MtCO2e (excluding LULUCF) by 2030. This represents 3–9% ambition gap. For more details on our projections, see the Assumptions tab.

To be 1.5°C compatible, current policies would need to reach at least 1,815 MtCO2e (excluding LULUCF) by 2030. Our 1.5°C modelled domestic pathway is based on global least-cost mitigation and defines the minimum level of emission reductions needed domestically to be 1.5°C compatible. It should be taken as the floor, and not ceiling, for domestic ambition.

Our planned policies projections of 2,370–2,400 MtCO2e (excluding LULUCF) reflects the EU’s 2030 indicative renewable energy goal (of a further 2.5%, totalling 45%) as well as policy proposals that have been announced but remain to be adopted, most notably is the Energy Taxation Directive. If the EU adhered to the full list of planned policies, then it would be close to achieving its 2030 NDC target, missing the mark by 1–2%.

The full spectrum of policies proposed and adopted under the Fit-for-55 and REPowerEU legislative packages have been effective in improving projected emission reductions by 2030, though some of the regulations are yet to come into effect.

Despite the enormous regulatory exercise that the EU has been pursuing, many gaps still remain, with loopholes and lax enforcement mechanisms in the policy design. Additional action is required to address these issues, including:

Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against modelled pathways and fair share) can be found here.

Policy overview

Economy-wide emissions across the EU have continued to fall since 2019, when the new European government at the time came to power, roughly by 6% from 2019 to 2022 (the last available data point). In June 2024, European Parliament elections were held, and President von der Leyen was re-elected as head of the European Commission. The new work plan for the next Commission has signalled a shift towards framing climate action in the context of decarbonising Europe’s industries, focusing on competitiveness on a global stage and an increasing attention towards developing a new market for carbon removals.

In its previous legislative cycle (2019–2024), the European Green Deal which encapsulated the Fit-for-55 package and REPowerEU legislative packages set out a path for the EU to achieve climate neutrality by 2050. Some key policies and regulations introduced and revised include the:

- Renewable Energy Directive (RED III)

- Energy Efficiency Directive

- new EU ETS II covering transport and buildings

- Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism

- Effort Sharing Directive

For more detail see the previous assessment from February 2024 here

In the past year, the final elements of the Fit-for-55 and REPowerEU packages were finalised and adopted prior to the June elections including the; Gas Regulation and Directive, Methane Regulation, Energy Performance in Buildings Directive and Carbon Removal Certification Framework, which are covered in more details for this assessment.

President von der Leyen plans to launch a “Clean Industrial Deal” building upon existing policies to pivot Europe’s industries. The plan focuses on scaling up manufacturing of net-zero emission technologies and investing in skilled workers to satisfy the growing domestic need for net-zero emission technologies, like electric vehicles (EVs) and heat pumps (von der Leyen, 2024a). With this revision to existing industry related policies, the EU aims to become a global competitor with China and the US in the green technology race. There will be a big push for expanding and improving rail networks and performance, which is a key measure needed to facilitate a modal shift to an alternative less carbon intensive mode of transport compares to airplanes and cars.

Power sector

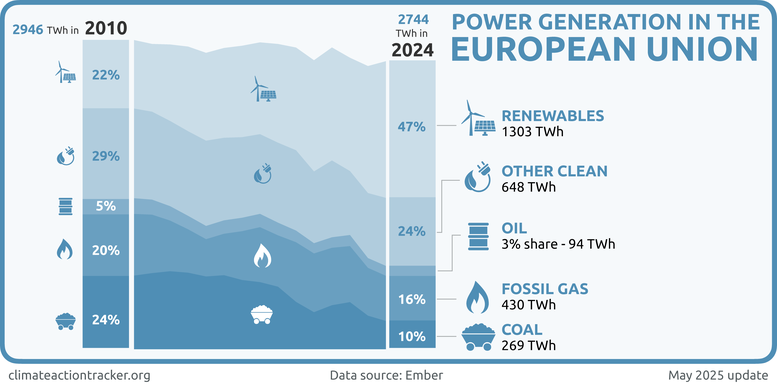

The EU is making progress, though slowly, on phasing out coal and ramping up renewables in its power sector, but fossil gas remains a sticking point with the EU sending mixed signals around its phase out. While the share of total electricity generated from renewable sources has increased to 49%, wind and solar generation deployment remains too slow.

Following the June 2024 European Parliamentary elections, the new Commission has reaffirmed its commitment to increase investments in modernising Europe’s electricity grids over the next legislative cycle (von der Leyen, 2024a). The EU Grid Action Plan announced in November 2023 will be crucial to modernise Europe’s electricity grid to prepare it for the incoming surge of renewables and increased demand for electricity by 2030 (European Commission, 2023c). While the plan will invest EUR 584 bn, it lacks specific target dates for many of its actions, putting their implementation at risk (Mindekova & Cremona, 2024).

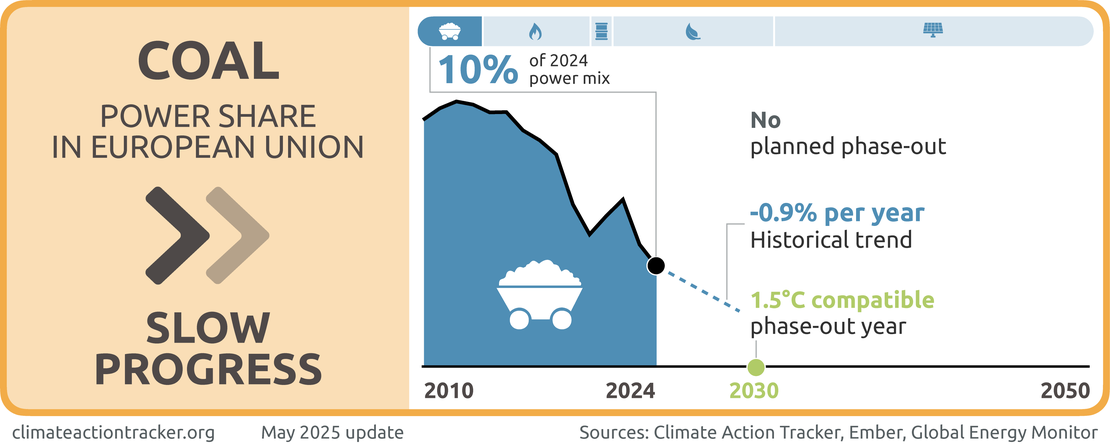

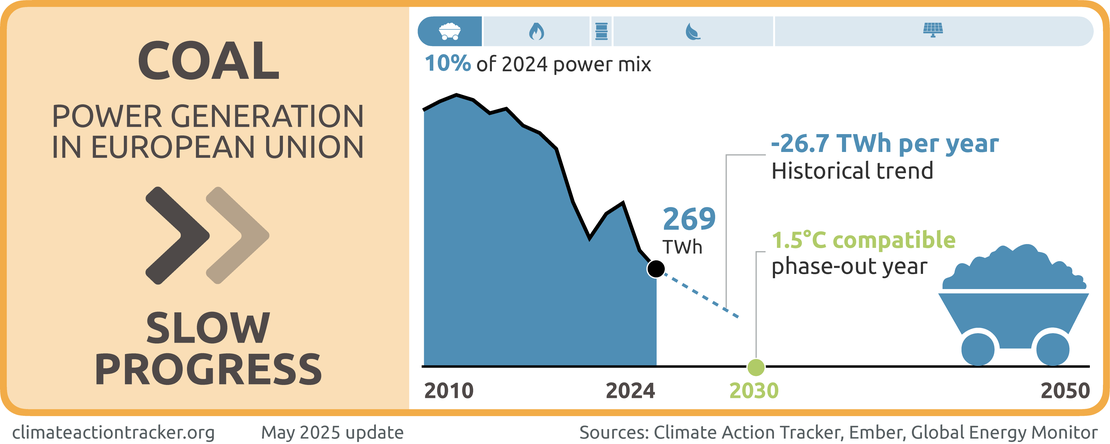

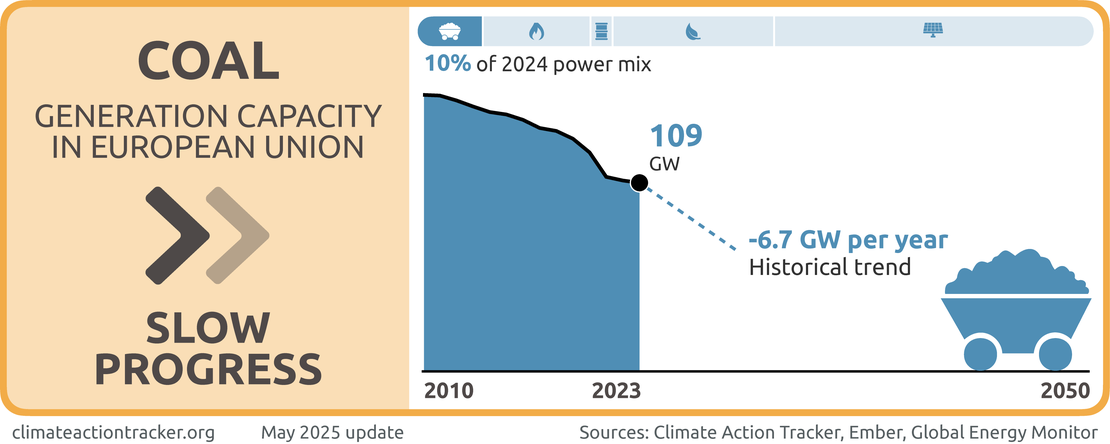

Coal

The EU’s share of coal in the power mix has decreased only marginally from 13% in 2020 to 10% in 2024. Despite this small share in the power mix and having signed up to the coal exit pledge at COP26, the EU has not committed to a coal phase-out date. Given the slow decrease of coal in the power and the lack of a phase out target, we evaluate the EU as making "Slow progress" on phasing out coal use in the power sector.

Though the EU did not include the coal exit as part of its 2023 NDC update, a large majority of the EU member states either don’t use coal power or have an exit date before 2030, a handful still have later dates. As of 2024, 20 EU member states already have no coal in their electricity generation or coal power phase-out dates prior to 2030, while 6 countries have a phase out date beyond 2030 and only one country has not committed to phase out coal entirely (Climate Action Tracker, 2023a). In 2023, France, Italy and Hungary delayed their coal exits but still maintain a deadline before 2030 (Beyond Fossil Fuels, 2024). To be 1.5°C-compatible, the EU needs to phase out coal by 2030 at the latest (Climate Action Tracker, 2023b).

The EU bloc does not seem to fund coal projects overseas. However, some European investors have investments or shareholdings in coal projects and major coal companies across several non-EU countries including India, China, the US, Indonesia and South Africa, classified as “green," and amounting to EUR 65 million as of April 2024 (Civillini & Rodriguez, 2024).

The 2021 Sustainable Financial Disclosure Regulations (SFDR) were supposed to be a transparency framework, introduced to prevent greenwashing and promote more sustainable investing. However it has been ineffective because Articles 8 and 9 of the SFDR inadequately categorise green investments. Article 8 is too broad in its sustainability scope, and Article 9 lacks consistency in defining what qualifies as a sustainable investment. The EU is now conducting an assessment on the effectiveness of this legislation (European Commission, 2024f). This presents the Commission with an opportunity to further close its policy gaps and resolve the loopholes for fossil fuel investments.

Fossil gas

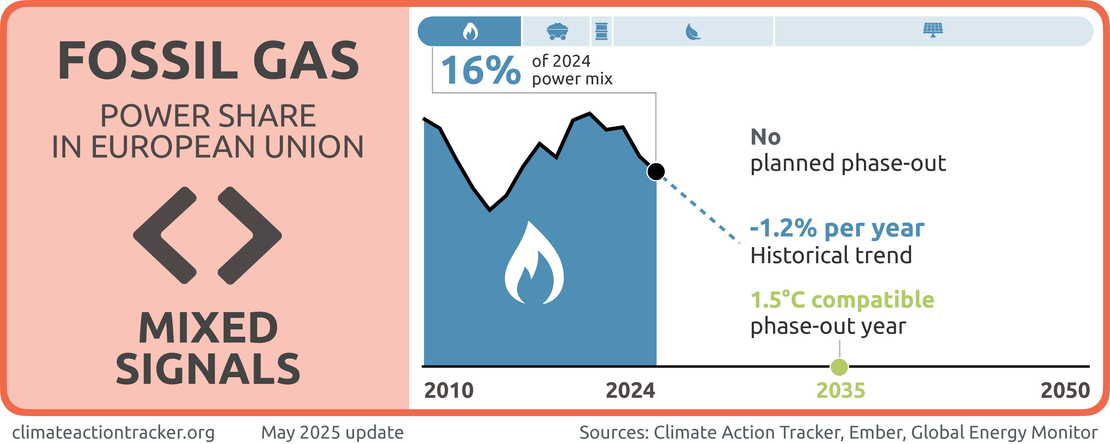

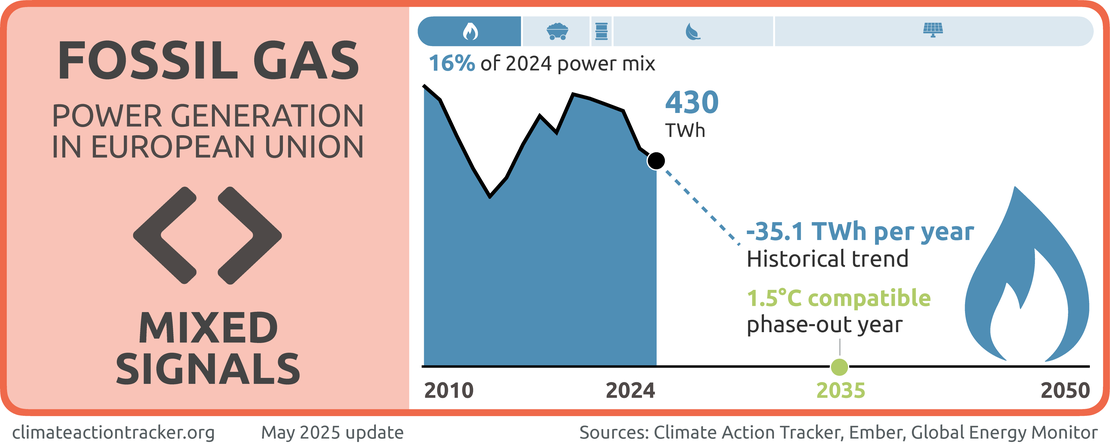

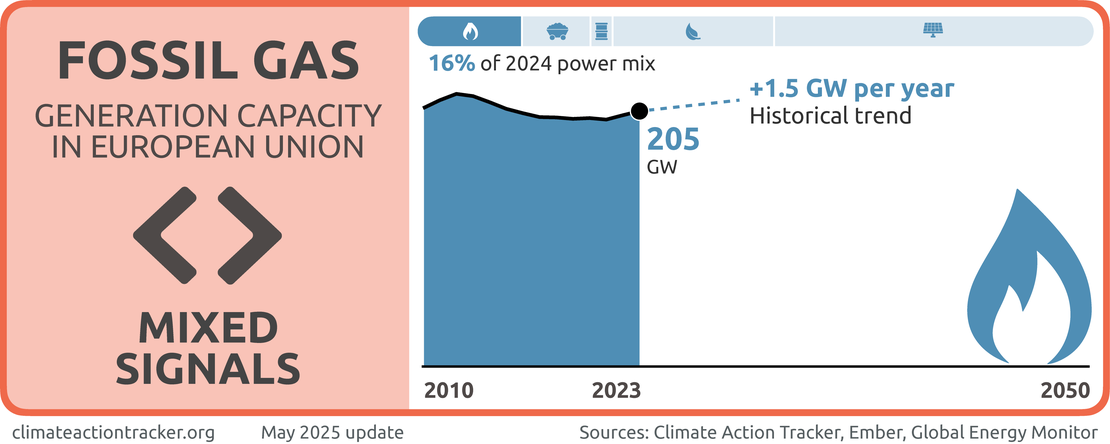

While the amount of electricity generated by fossil gas dropped in the last five years, it still makes up a sizable portion of the overall power mix at nearly 16% in 2024. At the same time, fossil gas generation capacity has grown. Like coal, the share of fossil gas in the overall power mix has decreased minimally over the last five years at just over 1% per year. Instead of setting a fossil gas phase-out date, the EU continues to invest in the buildout of LNG terminals and gas pipelines. We evaluate the EU’s progress on gas as sending “Mixed signals.”

The EU has agreed to extend its fossil gas demand reduction target until the end of March 2024 (Council of the European Union, 2023b). While the to focus on cutting demand and shifting to renewable sources is a positive development, the current pace is far too slow. Additionally, CAT analysis shows that the EU’s fossil gas strategy risks carbon lock-in and undermines global climate action. To be 1.5°C-compatible, the CAT finds that the EU would need to phase out fossil gas by 2035 (Climate Action Tracker, 2023b).

In its efforts to move away from Russian gas following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the EU and its member states have diversified their fossil gas imports from other countries in the form of LNG. This has been accompanied by massive investment buildout in LNG terminals and gas pipelines to the tune of EU 84 bn (Rozansk & Hassan, 2024). As a result, Europe now has an overcapacity of LNG facilities representing long-term stranded assets, further exacerbated by the decreasing demand for gas and forcing consumers to bear the high price of LNG (Jaller-Makarewicz, 2023).

Revised Gas Package

The EU recently adopted the revised Gas Directive and Regulation, intended to “shift from fossil gas to renewable and low-carbon gases, in particular biomethane and hydrogen, and to establish and regulate the upcoming market for hydrogen” (European Council, 2023). Positively, it requires fossil gas distribution operators to develop plans to decommission gas networks and establishes a new and independent governance structure for the future transmission of hydrogen. This new hydrogen market is intended to prioritise the hard-to-abate sectors but the legislation fails to introduce guardrails to guarantee this. There are other concerns:

- The legislation covers low carbon gases but fails to provide a definition as to what a low carbon gaseous fuel is, risking that low carbon fuels could be derived from fossil fuels.

- Long term fossil gas supply contracts are also allowed to run until 2049.

The gas package was a missed opportunity to introduce a legally binding commitment to phase out fossil gas. Needless to say that the current policy direction is still heading in the wrong direction.

There remains a mismatch between current energy needs and the time needed for all of these projects to go online, which makes them difficult to justify as low carbon alternatives when investment in energy efficiency can be brought online instead. The need for such a significant investment in fossil gas infrastructure has been countered by an assessment indicating that the EU can do without Russian gas without investing heavily into fossil fuel infrastructure (European Climate Foundation, 2022).

Renewables

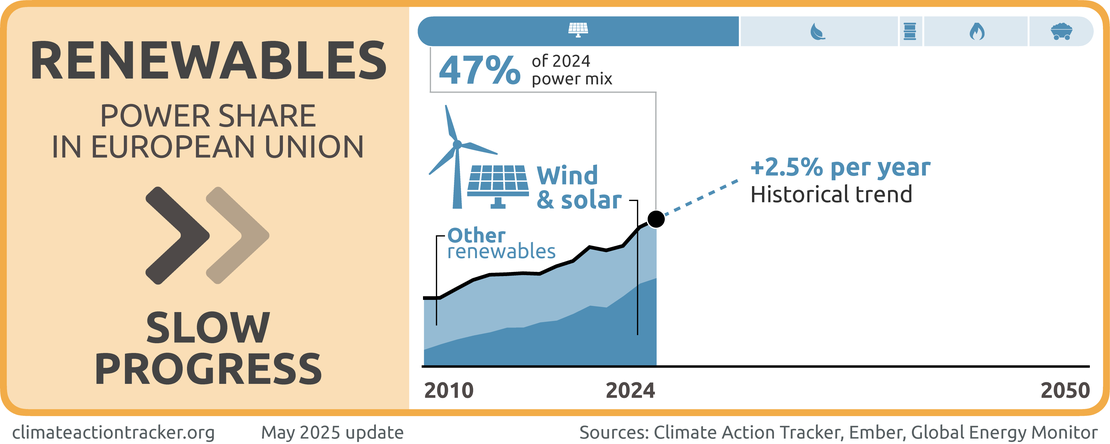

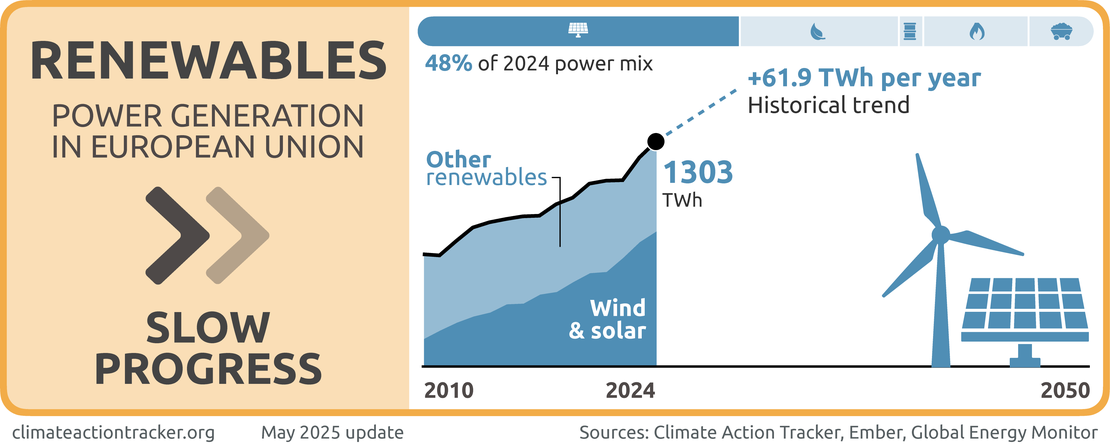

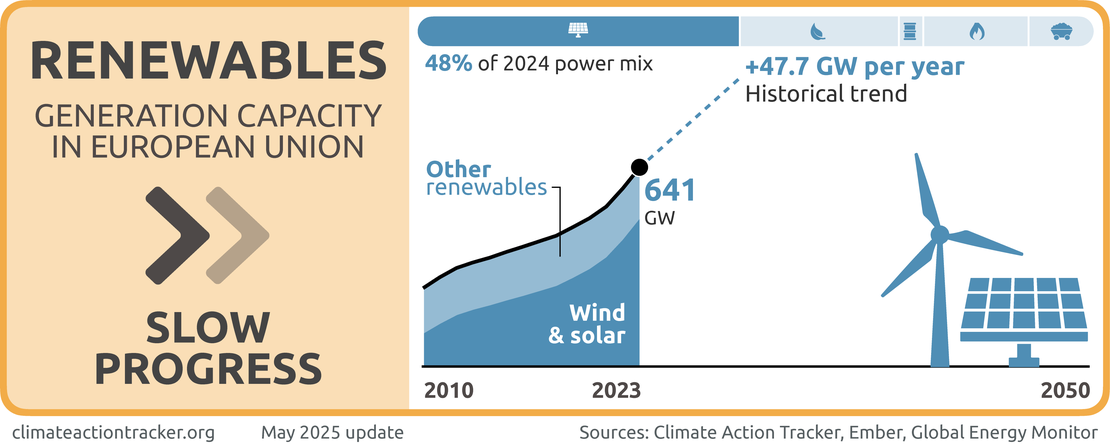

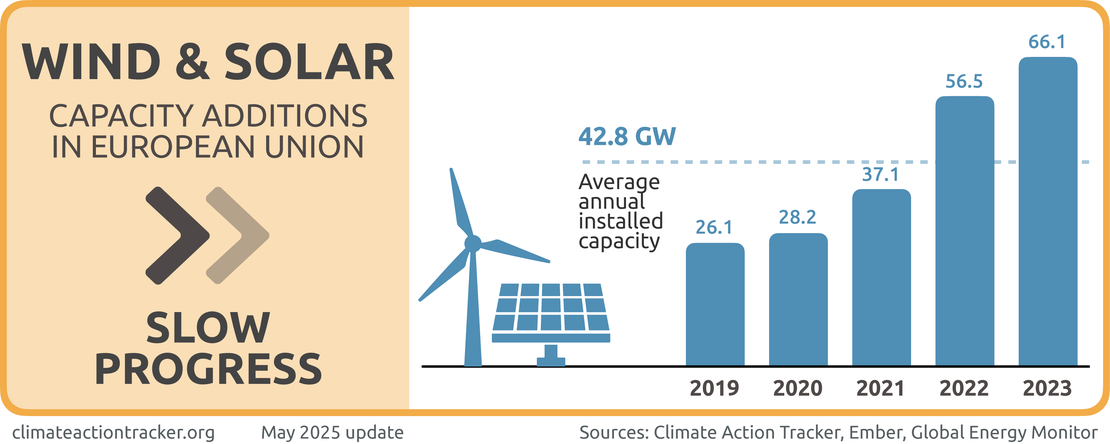

Renewables make up about half of the EU’s power mix with wind and solar generating about 28% of electricity in 2024. Other renewables, such as hydro and bioenergy, contributed the remaining 19% to total 47%. Though wind and solar generation has been increasing at 2.24% per year over the last five years, it is still at too slow a pace. The EU would need to see the historical trend for wind and solar increase to over 2.5% per year over the last five years or increase the share of renewables in the power mix to over 60% to move into the “Making headway” category under our evaluation. To align with 1.5°C compatible benchmarks, the EU would need to fully decarbonise the power sector by 2035 (Climate Action Tracker, 2023b). We evaluate the EU as making “Slow progress” on ramping up renewables in the power sector.

The EU has a binding renewable energy target of 42.5% and an indicative target of 45% by 2030 across all sectors set by the revised Renewable Energy Directive. Under the REPowerEU package, the Commission has indicated that the EU would need to achieve 69% of renewable energy in power generation to achieve this overarching renewable target of 42.5% – 45%. Member states are expected to outline how they will achieve their share of this target in the updated NECPs which were due in June 2024. As of May 2025, 23 out of 27 member states have submitted their final updates.

The draft 2023 NECPs highlighted that their combined ambition was not enough to achieve the EU’s 2030 targets (European Commission, 2023b). While the renewable energy targets in the NECPs have improved, in many cases the NECPs did not include the supporting measures necessary to achieve the targets. The final member state NECPs missing the submission deadline, and a lack of concrete measures, does not instil confidence that member states will follow through on their climate commitments (Climate Action Network, 2024).

Nuclear energy

Nuclear power generated 24% of electricity in 2024 which the CAT does not see as a viable long-term solution to the climate crisis. The EU included nuclear energy in the Net-Zero Industry Act (NZIA), recognising it as a "strategic" technology. The NZIA supports nuclear technologies like small modular reactors, highlighting their potential to provide low-carbon energy with minimal waste, crucial for decarbonisation and energy security (European Commission, 2023d). In its 2040 climate target communication, the Commission did not specify any target or actions towards nuclear capacity build up but reaffirms nuclear a low carbon fuel needed to achieve its targets.

Although nuclear electricity generation does not emit CO2, the CAT doesn’t see nuclear as the solution to the climate crisis due to its risks such as nuclear accidents and proliferation, high and increasing costs compared to alternatives such as renewables, long construction times, incompatibility with the flexible supply of electricity from wind and solar and its vulnerability to heat waves.

There have been no new policy updates since the CAT’s last assessment. For more detail see the previous assessment from February 2024 here .

Industry

The EU’s industrial emissions, both energy related and from industrial processes, accounted for about 24% of its total GHG emissions in 2021 (Climate Analytics, 2024; UNFCCC, 2023). Industrial emissions have been falling on average about 2.3% per year but this is not fast enough and the EU’s industry will need to accelerate this 1.3 times faster than its current trend to reach 1.5°C compatibility (European Climate Neutrality Observatory, 2024b).

The EU has not signed the Beyond Oil and Gas (BOGA) declaration but eight of its member states have. Six member states — Denmark, France, Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Sweden — are core members of the Alliance and have committed to ending oil and fossil gas exploration and development (Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance, 2021).

To decarbonise its industries, the EU introduced indicative targets in the revised Renewable Energy Directive (EU 2023/2413) for the share of renewables in industry. Article 22 requires the industry sectors in member states to increase the share of renewable energy by an average annual rate of 1.6% between 2021 and 2030. This annual 1.6% indicative benchmark was watered down by the Commission from the initial 1.9% growth rate it estimated it would need to deliver on the REPowerEU objectives (European Commission, 2022a).

The revised Renewable Energy Directive also requires that only 42% of incorporated hydrogen be derived from renewable energy by 2030 and 60% by 2035. This means that the industry will use a mix of renewable and fossil fuel derived hydrogen. This design will allow industries to start their shift to hydrogen but access cheaper fossil fuel derived hydrogen until the green hydrogen is available at scale and affordably. The EU does not have any provisions to fully eliminate fossil fuel derived hydrogen from industry beyond 2035, which risks the long-term dependence on fossil derived hydrogen.

Green hydrogen

The Commission’s Hydrogen Strategy sets out that installed capacity of electrolysers in the EU should reach 40 GW by 2030, resulting in the production of up to 10 million tonnes of green hydrogen, complemented with similar capacity installed in neighbouring countries (European Commission, 2020). The EU hydrogen policy framework has several key gaps hindering market development and does not go far enough to address issues such as high-cost entry barriers and uncertainties. At present, renewable hydrogen is also much more expensive than fossil fuel-based hydrogen. Financial support is fragmented, with a shortage of targeted funds necessary to meet the 2030 REPowerEU goals. Additionally, the EU lacks a clear definition for low-carbon hydrogen, and is only expected to develop a methodology by 2025 as part of the Delegated Act of the revised Gas Regulation.

Developing a net zero technology Industry

To tackle replacing industrial technology with cleaner alternatives, the EU has been developing a nexus of polices to facilitate the growth of (1) net zero technology industry and (2) industrial carbon removals, encapsulated by the:

- Net Zero Industry Act (NZIA) (EU) 2024/1735, and more broadly the Green Industrial Plan

- Industrial Carbon Management Strategy

- Carbon Removal Certification Framework (proposal)

- 2040 climate targets (proposal)

In June 2024, the Net Zero Industry Act entered into force (European Parliament & European Council, 2024c). It focuses on 19 net zero technologies. It also includes the objective of developing annual injection capacity for carbon capture and storage of 50 MtCO2e by 2030 that should be used to mitigate residual emissions. These capacities should be developed by oil and fossil gas companies proportionally to their current oil and gas production levels.

The NZIA will be crucial to operationalising the direction set by the Industrial Carbon Management Strategy (ICMS) (European Commission, 2024d). The ICMS lays out how it plans to scale up industrial carbon removals to deliver the EU’s climate neutrality objective, most notably from bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCs) and direct air carbon capture (DACC).

It sets out a target to reach 50 MtCO2e in carbon removals annually by 2030. The ICMS is strongly linked to the proposed 2040 targets, which are yet to be adopted. In its impact assessment the Commission envisions it would need about 75 MtCO2e of industrial carbon removals from BECCs and DACCs by 2040. Additionally, the Commission will create policy options and support mechanisms for industrial carbon removals, including considerations on whether and how to integrate them into the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) but this is not expected until the planned revision of the ETS in 2026 (EPG, 2024).

In April 2024, the political agreement was reached on the Carbon Removal Certification Framework (CRCF) but is still to be adopted (Carbon Gap, 2024a; European Commission, 2022b). The CRCF seeks to establish a framework to certify the emission removals from carbon farming, carbon storage in products and industrial carbon removals (from technologies like Direct Air Carbon Capture and storage (DACCS) and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCs). The CRCF is the mechanism to deliver on the goals of the ICMS and lays out the role the CDR will play. The CRCF gives the Commission the ability to assess options for CDR and CCS targets.

The CRCF is riddled with concerning elements that could go against climate action. The regulation lacks a distinction between emission reductions and removal, potentially allowing removals to offset emissions that should be reduced. It also risks offsetting and greenwashing through the permitting of sales of carbon credits as offsets in voluntary carbon markets, especially if large emitters are allowed to buy these credits.

The 2040 climate target communication keeps the role of CCS in the power sector vague under the proposed 2040 targets. This is worrying as the application of CCS to certain sectors is left open to interpretation. The incoming Commission has the opportunity during the subsequent expansion of the Industrial Carbon Management Strategy and Clean Industry Deal to clearly commit to no CCS in the power sector.

Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) refers to technologies which use engineered methods to capture CO2 from a source and store it geologically. CCS can be applied to a range of different CO2 sources in different sectors. CCS technologies are neither commercially viable nor proven at scale, despite large public subsidies for research and development globally.

Heavily relying on unproven CCS for power generation simply prolongs the use of fossil fuels, diverting attention and resources away from the necessary and urgent switch to renewable energy generation that drives down actual emissions.

The use of CCS should be limited to industrial applications where there are fewer options to reduce process emissions—not to reduce emissions from the electricity sector where renewables are cost-effective mitigation alternatives, not least because CCS doesn't remove 100% of emissions from power plants.

Transport

Transport is the only major sector in the EU where emissions have increased over the last 30 years: emissions in 2022 followed an upward trend of 2.7% compared to 2021. It is too early to say whether emissions from the sector have peaked: the economic rebound and trend towards bigger vehicles may undermine the impact of increasing EV sales on emission levels.

The EU has introduced several policies and regulations to reduce emissions from the transport sector across all transport modes. These include but are not limited to:

- Revised Renewable Energy Directive (EU) 2023/2413, through the adoption of sectoral renewable energy targets,

- Revised Regulation strengthening CO2 emission performance standards for new cars and vans (EU) 2023/851, which established a ban on the sale of combustion engine cars by 2035.

- Revised Regulation on the trans-European transport Network (EU) 2024/1679

- New EU ETS II which covers road transport emissions from 2027

In 2023, electric vehicle (battery electric and plug-in hybrid) made up 22% of vehicle sales. To be 1.5°C compatible in line with the Paris Agreement, the CAT finds that the EU would need to achieve 95–100% sales of light-duty electric vehicle sales by 2030 (Climate Action Tracker, 2024). This is five years earlier than the EU’s current target of 2035. The EU did not sign the Zero Emissions Vehicle pledge at COP26 and did not include this target in its NDC.

In President von der Leyen’s political guidelines for the next four years in office, she hinted that the 2035 ban on the sale of internal combustion engine vehicles might be watered down through the increased use of alternative fuels to achieve the ban (Mathiesen et al., 2024). The ban on fossil fuel car sales has an exemption to allow synthetic e-fuels to continue beyond 2035. Positively, the guidelines also pushes for greater improvements to the EU’s rail network to encourage a stronger modal shift towards rail (von der Leyen, 2024b).

In June 2024, the EU adopted the revised Regulation on the trans-European transport Network (TEN-T) (European Parliament & European Council, 2024b). The regulation intends to create the enabling conditions to scale up zero emission transport modes, improving connecting and promoting a modal shift to more share and zero mission transport.

While no new transport regulations have been adopted since the last CAT assessment in February 2024, some have been revised or are still pending agreement such as the CO2 emission standards for heavy-duty vehicle and the Green Freight Package.

Gaps still remain for some regulations. For example, the FuelEU Maritime Regulation (EU) 2023/1805 (European Parliament & Council of the European Union, 2023c) and the Alternative Fuel Infrastructure Regulation (EU) 2023/1804 (European Parliament & European Council, 2023) consider LNG a “low carbon fuel” in shipping. As LNG is a fossil fuel, its prolonged or expanded use will make it difficult to achieve future emission reductions given the long lifetime of ships and infrastructure, resulting in stranded assets.

To reach full decarbonisation in the transport sector globally by mid-century, the EU would need to increase the share of zero emission fuels (electricity, hydrogen and biofuels) from 7% in 2019 to 55% by 2030. This covers all modes of domestic transport collectively (i.e. road, rail, domestic aviation and maritime travel) (Climate Action Tracker, 2024).

Tariffs on Chinese EVs

In October 2024, the EU Commission announced new tariffs on battery EVs manufactured in China on the basis that the Chinese government unfairly subsidies its EVs, undercutting European car manufacturers. Individual duties will range between 17.4% to 37.6% depending on the Chinese manufacturer (European Commission, 2024e).

To be 1.5°C compatible, the EU needs continued exponential growth in EV sales, needs a lot of them to meet demand, and needs to make it affordable for consumers (Climate Action Tracker, 2024). One of the major barriers to this is affordability. Chinese EV models sold across EU member states are typically cheaper than European manufactured vehicles, which could affect consumer choices.

Buildings

In 2021, buildings accounted for 13% of the EU’s total GHG emissions (Climate Analytics, 2024), consuming 40% of the EU’s final energy consumption. The buildings sector has traditionally been heavily reliant on fossil gas and oil. High energy prices triggered by Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine is having some impact on consumer behaviour and spurring policy action in the sector. GHG emissions in buildings have been steadily falling since 1990, but not fast enough (European Climate Neutrality Observatory, 2024a).

The main legislation driving the decarbonisation of the EU’s building sector fall under:

- Revised Renewable Energy Directive (EU) 2023/2413

- Revised Energy Efficiency Directive (EU) 2023/1791

- Revised Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EU) 2024/1275

- New EU ETS II which covers buildings sector

The revised Renewable Energy Directive sets an EU wide target to achieve 49% share of renewables in the final energy consumption in buildings by 2030 (European Parliament & Council of the European Union, 2023a). The revised Energy Efficiency Directive sets a binding target to reduce the final energy consumption by 11.7% relative to the 2020 or a target of 763 Mtoe of final energy consumption by 2030 across all sectors (European Parliament, 2023).

The EED lacks robust measures specifically targeting the building sector, focusing instead on general improvements in energy efficiency and renovation rates linked to the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive. As of early 2024, no updated NECP submissions from member states fully comply with EED requirements, revealing a concerning lack of commitment. Furthermore, only twelve member states recognise the broader renovation obligation for public buildings (Chapelot et al., 2024), highlighting significant implementation gaps that undermine the EU's climate ambitions.

According to the reform of the EU ETS agreed in early 2023, the buildings sector will be covered by a new emissions trading scheme (EU ETS II) from 2027 onward. The requirement to purchase emission allowances to cover the sale of fossil fuels used in the transport and building sectors will further increase the incentive for home insulation and installation of clean sources of heating.

The revised Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD), adopted in 2024, includes several important measures aimed at achieving a zero emission building sectors by 2050. One of the most significant changes is the mandate that all new buildings must meet "zero emission" standards by 2030. While a step in the right direction, the proposal was watered down from the EU Commission's initial plan, which called for binding EU-level minimum energy performance standards.

While the EPBD targets a 3.5% annual renovation rate by 2030, which aligns with 1.5°C compatible benchmarks, the EU’s current renovation rate stands at only around 1% annually (Climate Action Tracker, 2020; European Climate Neutrality Observatory, 2024b). The Directive also targets the renovation of 15% of the EU's building stock by 2030, but this is widely regarded as insufficient to meet climate goals (European Climate Neutrality Observatory, 2024a). The table below provides a summary of the main targets set out in the EPBD (BPIE, 2024).

| Target | Details | Timeline | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS) | Renovate 16% of non-residential buildings and improve 26% of the worst-performing non-residential buildings through mandatory standards |

16% by 2030 26% by 2033 |

||

| Annual Renovation Rate | Achieve a 3.5% annual renovation rate of the overall building stock to enhance energy efficiency | By 2030 | ||

| Renovation of Residential Buildings | Renovate 22% of the lowest-performing residential buildings to reduce energy consumption | By 2030 | ||

| Total Building Renovations | Renovate at least 35 million buildings to significantly improve energy performance and reduce emissions | By 2030 | ||

| Zero-Emission Buildings | New or deeply renovated buildings must meet zero-emission criteria, consuming very low energy | By 2030 | ||

| Energy Consumption Limits | Set energy consumption limits to a maximum of 60 kWh/m² for Mediterranean climates; 75 kWh/m² for Nordic climates | By 2030 | ||

| Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs) | Update EPCs to enhance their effectiveness, ensuring better transparency about energy performance | Ongoing | ||

| Solar Energy Integration | Mandate solar installations on all new public and commercial buildings to promote renewable energy |

From 2027 (new) By 2028 (existing) |

||

| Funding Mechanisms | Establish a Social Climate Fund with a budget of €65 billion to support vulnerable households and financing for energy-efficient renovations | Ongoing | ||

| Average Primary Energy Use Reduction | Member States to reduce average primary energy use by 16% by 2030 and 20-22% by 2035, with at least 55% of this reduction from renovating worst-performing buildings |

By 2030 By 2035 |

||

| National Action Plans | Member States required to submit national plans to outline how they will meet the set energy efficiency targets | By 2024 and every two years thereafter | ||

| Binding Intermediate Targets | Member States must set binding intermediate targets for the renovation of public buildings | By 2024 | ||

| Inclusion of a ‘renovation passport’ | Introduce a ‘renovation passport’ to guide homeowners in planning and prioritising energy improvements | Ongoing | ||

The revised EPBD missed an opportunity to fully address the issue of locking in fossil fuel heating systems, by introducing an ambiguous ban on fossil fuel boilers by 2040, while it did ban member states from subsiding the installation of fossil fuel boilers from 2025. The 2040 ban leaves the member state to decide whether or not they wish to include this in their national phase-out plans (Verplancke et al., 2024).

The implementation timeline of the revised EPBD is too slow. Key milestones, such as mandatory solar installations for new public and commercial buildings by 2027 and minimum energy performance standards for existing buildings by 2033, push essential changes far into the future. This drawn-out schedule is seen as inadequate to meet the urgent decarbonisation goals needed to address the climate crisis.

To reach full decarbonisation in the buildings sector globally by mid-century, the EU would need to reduce the emission intensity (kgCO2/m2) in residential buildings and commercial buildings by 60% and 75% respectively by 2030, compared to 2015 levels. In energy saving terms, the EU would need to reduce the energy intensity (kWh/m2) by 30% and 25%, respectively, by 2030.

Agriculture

Agriculture accounts for 11% of the EU’s total GHG emissions in 2021 (UNFCCC, 2023). The EU agricultural sector generates about 60% of its emissions from methane, nearly all of which come from livestock, primarily through enteric fermentation and manure management (Eurostat, 2022). Despite this, methane reduction efforts remain insufficient.

While the EU is a co-initiator of the Global Methane Pledge, aiming to cut global methane emissions by 30% below 2020 levels by 2030, only 11 member states have committed to reducing methane from livestock, covering less than 3% of the EU’s livestock units. Leaked reports indicate the EU is not on track to meet its methane reduction target, signifying the need for stronger measures (Ainger, 2022; Changing Markets, 2022). Previous Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) efforts from 2014–2020 had limited success in cutting emissions, focusing instead on increasing CO2 removals (European Union, 2022).

Early 2024 saw widespread protests by farmers against the climate and nature regulations under the Green Deal reach a fever-pitch across many member states, particularly around cutting subsidies for fossil fuels and pesticides (Dwyer, 2024). This prompted the EU to backtrack on some of its initiatives to cut emissions from agriculture under the proposed 2040 target, including on introducing sectoral targets for the first time. The Commission also rapidly passed a new regulation (EU 2024/1468) to limit some of the environmental requirements for farmers under the CAP (2023-2027), which weakened its environmental impact (European Parliament & European Council, 2024a).

The European Court of Auditors (ECA) criticised the 2023–2027 CAP strategic plans for falling short of the EU’s climate and environmental ambitions. Despite being more ambitious than previous plans, the new CAP still lacks alignment with the European Green Deal targets. The ECA recommended that the Commission promote more environmental best practices, estimate CAP’s contribution to the Green Deal, and improve its monitoring of climate and environmental outcomes (ECA, 2024).

Key to the EU achieving its 2040 targets would be the introduction of an emission reductions target for the agricultural sector combined with a levy on agricultural emission. In June 2024, Denmark took a first step in this direction by becoming the first country to introduce an agricultural carbon tax and is pushing for this to be applied at an EU level (Mooney et al., 2024) .

The influence of farmer protests were significant enough to mark a shift in the EU’s tone on regulating farmers. Critically, the EU will need to find alternative pathways in supporting farmers as they transition to decarbonise and adapt to climate impacts but continuing with exemptions risks failing to deliver on net zero by 2050.

Forestry

Since 1990, the land use, land-use change and forestry sector (LULUCF) had constituted a sink of emissions averaging around 300 MtCO2e. However, since 2017, the sink has decreased significantly, amounting to around 230 MtCO2e in 2021.

The EU recently agreed to revisions to the LULUCF regulation (European Parliament & Council of the European Union, 2023d), which governs the sector. It increased its 2030 target to 310 MtCO2e, up from the 225 MtCO2e limit referenced in its Climate Law. The revisions included individual targets for each member state towards the 310 MtCO2e level. While enhancing the size of the land sink is positive, it should not undermine the level of ambition in other sectors.

The EU’s incoming Carbon Removal Certification Framework will also have ramifications for emission in the forestry sector (Carbon Gap, 2024b; European Commission, 2022c). Worryingly, the CRCF is riddled with concerning elements that could work against climate action. The regulation lacks a distinction between emission reductions and removal, potentially allowing removals to offset emissions that should be reduced. It also risks offsetting and greenwashing through the permitting of sales of carbon credits as offsets in voluntary carbon markets, especially if large emitters are allowed to buy these credits (EEB, 2024). For more details on the Carbon Removal Certification Framework, see the Industry section.

In the impact assessment for the 2040 climate targets, while not yet proposed, modelling indicated that the removals from LULUCF in 2040 could amount to somewhere between 215 MtCO2e and 376 MtCO2e with 317 MtCO2e as the central value(European Commission, 2024b). Our assessment of the EU’s proposed 2040 target indicates that the EU intends to achieve 86% emissions reductions by 2040 compared to 1990, excluding LULUCF emissions but including removals from industrial technologies such as DACCS and BECCS. This means that the EU will need to rely on expanding its LULUCF sink to achieve the remain 4–9% emission reductions. Additionally, even the largest estimated LULUCF sink of 376 MtCO2e under consideration is not sufficient to reach the 95% emission reduction.

Waste

Waste sector emissions have continuously fallen since the mid-90s, dropping by 40% between 1990 and 2021 (European Environment Agency, 2023a).

Regulation of waste sector emissions is covered by the Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR), along with those from transport, buildings, and agriculture. Combined, emissions from these sectors needs to decrease by 40% below 2005 levels by 2030 (European Parliament & Council of the European Union, 2023e).

As of 2024, the European Parliament has voted to strengthen the proposed Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) scheme for textiles. The European Parliament's approval of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) for textiles is seen as a step forward, but it lacks specific waste prevention targets and effective management strategies.

Meanwhile, the EU Council has prioritised textile reforms, neglecting critical food waste reduction measures. This approach is viewed as insufficiently ambitious, highlighting the need for stronger commitments to ensure both textile and food waste are managed effectively for sustainable outcomes (Zero Waste Europe, 2024) . The current design may not adequately incentivise producers to improve product design for longevity and recyclability, with some suggesting that the focus remains too heavily on waste management rather than preventing waste generation.

Methane

In 2022, methane emissions accounted for 11% of the EU’s total GHG emissions. The majority of these emissions came from the agricultural sector, followed by waste management and energy. Methane emissions have fallen about 60% since 1990 (UNFCCC, 2024).

The EU signed the methane pledge at COP26 in 2021. Methane is covered in the overall scope of the EU’s latest NDC from 2023 but is also specifically mentioned in the context of mitigating methane emissions from maritime transport under the revised EU ETS. In 2020, the EU released its methane reduction strategy laying out its intention to cut emissions from energy, agriculture, and waste.

As part of the strategy, in 2024, the EU adopted the regulation on methane emission reduction in the energy sector (EU) 2024/1787 (European Parliament & European Council, 2024d), covering emissions from oil and fossil gas exploration, production, transmission, distribution, coal mining and imports of fossil fuels.

The regulation introduces new measures to measure, report and verify (MRV) methane emissions, methane abatement measures and a ban on routine venting and flaring. While a step in the right direction, the regulation does not go far enough – starting with the lack of an overarching methane reduction target and prolonged implementation timeline, which does not reflect the urgency and pace needed.

In addition, many exemptions and loopholes diminish the regulation's effectiveness. The regulation excludes the petrochemical sector and LNG consumption. Methane intensive LNG can be expected to grow considerably, given the signal that other EU polices are pushing. For example, the FuelEU Maritime for LNG fuel in shipping, as well as the build up of LNG infrastructure over the past few years following the shift away from imported Russian gas (Climate Action Network Europe, 2023). A recent study finds that LNG as a fuel has an emission footprint 33% greater than that of coal due to the associated methane leakage (Howarth, 2024). Additionally, despite representing the largest source of methane, the agricultural sector is not included. Instead, it is counted under the overall GHG emission reduction target for member states under the Revised Effort Sharing Directive.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter