Country summary

Overview

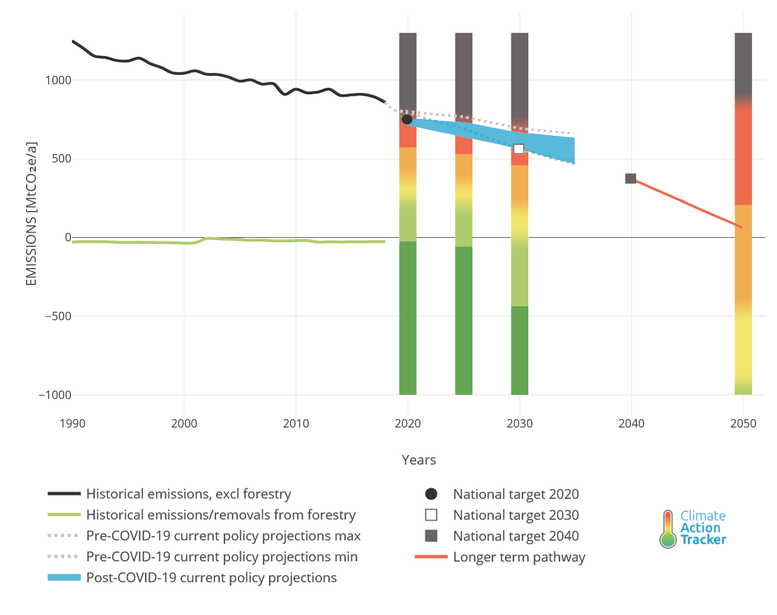

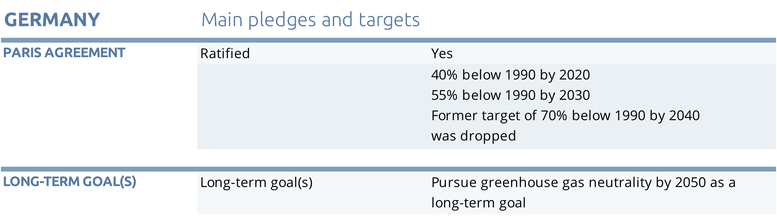

The German government’s Climate Action Programme 2030, adopted in December 2019, does not contain enough policy measures to meet its own 2020 or 2030 emissions reduction targets, which themselves are outdated and insufficient. The targets might be met only with the impact of COVID-19 under a worst-case scenario. The CAT rates Germany’s 55% emissions reduction target for 2030 (agreed in 2010) as “Highly Insufficient”, it needs to be strengthened to be compatible with the Paris Agreement.

We expect Germany’s GHG emissions in 2020 will be 9-11% lower than in 2019. Restricted mobility and quarantine measures due to the COVID-19 pandemic significantly reduced industrial production and energy demand, and put an almost complete stop to passenger flights. In 2020, GDP is expected to decrease by 6.8 – 8.8%. In response the German governing coalition agreed on a €130 billion economic stimulus package in June 2020, including a €50 billion “package for the future”. While the overall focus on climate-friendly technologies was welcomed, NGOs criticised the government for missing the opportunity to fully align the programme with its climate targets.

The government’s Climate Action Programme lacks a clear plan to reach its envisaged goal of climate neutrality by 2050. The new, positive structural elements to German policy - a coal phase-out, a carbon price on fuels in buildings and transport, and an overarching climate law - lack sufficient quantitative ambition to meet the government’s targets, let alone the Paris Agreement’s mitigation challenge.

The 2038 coal phase-out date is almost a decade too slow to meet the objectives of the Paris Agreement, and a new coal-fired power station went online in May 2020. The original phase-out schedule was proposed by a multi-stakeholder commission and included compensation to local people and companies of up to €45 billion. The corresponding coal exit law, adopted in July 2020, significantly watered down the already weak coal commission recommendations, and has been broadly criticised by civil society actors and scientific advisors.

The government had previously acknowledged that it would not meet its 40% reduction target for 2020 but is now likely to reach it because of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The CAT’s current policy projections indicate emissions reductions of 41% to 43% below 1990 levels.

Meanwhile, after previously leading in providing new renewable energy capacity in electricity, capacity additions of wind and solar have slowed down significantly, putting the whole industry at risk. 2019 saw solar PV installations significantly pick up again, but onshore wind fell to the lowest level in 20 years. More jobs were lost in the last decade in each sector than people currently employed in the coal sector. The measures in the Climate Action Programme are not necessarily enough to accelerate development to meet the government’s 2030 renewable electricity target of 65%, which itself is insufficient.

On the basis of the September 2019 Climate Action Programme, Germany adopted a national climate law and associated regulations. It includes the national 2030 climate target and the “commitment to pursue greenhouse gas neutrality by 2050 as a long-term goal”. The national climate law distributes the 55% reduction by 2030 target to sectors and gives implementation responsibility to sector ministries. While this improves accountability, the associated measures are not ambitious enough.

One of the main instruments for achieving emission reductions is the new carbon price for the buildings and transport sectors with an initial price of €25/tCO2. However, the impact of this new instrument is difficult to predict.

Based on this target we rate Germany “Highly Insufficient”.

According to our analysis, it is likely that the COVID-19 lockdown and ensuring economic crisis will allow Germany to meet its 2020 target and potentially even its 2030 target under an economic worst-case scenario. It is not due to climate mitigation efforts.

The December 2019 Climate Action Programme distributes the 55% reduction target by 2030 to sectors and gives implementation responsibility to sector ministries. In the event of the targets not being met, the Building and Transport Ministries would be responsible for paying the fines due under EU regulation. In a pre-COVID-19 scenario Germany would have faced an EU compensation bill of up to €35 billion (Höhne and Fekete, 2020). The Climate Action Programme measures are not ambitious enough, and have been heavily criticised (Enkhardt, 2019a).

The new climate law includes the “commitment to pursue greenhouse gas neutrality by 2050 as a long-term goal” (German Government, 2020a). This was included despite the difficulties the German government had earlier in 2019 to clearly commit to such a goal.

In the energy sector, CO2 emissions from coal power have declined in recent years and the share of renewable energy in electricity has risen, but in 2019 about one fifth of German CO2 emissions still came from coal-fired power plants. Capacity additions for all major renewable energy technology are still not sufficient, with onshore wind almost coming to a standstill in 2019 after a change in regulation and only very slightly picking up again in 2020. Some studies suggest the government’s currently implemented policies will only just meet its target to raise the share of electricity generated from renewable energy to 65% of gross electricity consumption by 2030, while several other studies suggest that current measures are not sufficient (EWI, 2020; German Federal Environment Agency, 2020; Oei et al., 2019).

In January 2019, a multi-stakeholder Coal Commission found a compromise for phasing out coal-fired power generation (Kommission „Wachstum Strukturwandel und Beschäftigung“, 2019). Of the 43 GW of currently-installed coal capacity, the commission proposed shutting down 13 GW by 2022, an additional 13 GW by 2030 and completely phasing out electricity generation in coal power plants by 2038, with the option of bringing this date forward to 2035.

This compromise was found only by an agreement to compensate the affected regions (€40 billion) and the affected companies operating the coal power plants (an additional €4.35 billion) (Agora Energiewende, 2019; Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie, 2019). The original compromise received broad societal consensus. However, the schedule is still not fast enough to be compatible with a 1.5°C pathway that would require a coal phase-out by OECD countries by 2030 (Climate Analytics, 2018). And while the government promised to enshrine the coal exit roadmap into law by November 2019, it was only adopted in July 2020 and watered-down significantly from the already weak coal commission recommendations.

As of 2021, emissions trading will be introduced on fuels in the transport and building sector. Certificates will be distributed for a fixed price of €25/tCO2 in 2021 rising to €55/tCO2 in 2025. It is difficult to predict the overall impact of this new instrument.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter