Current Policy Projections

Economy-wide

It is likely that Germany will meet its 2020 target and could potentially even reach the 2030 target under an economic worst-case scenario, but only because of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown measures and ensuing economic crisis, not climate mitigation efforts.

In 2018, Germany’s emissions (excl. LULUCF) were 31.3% below 1990 levels or 858 MtCO2e in total. That is 36 MtCO2e or 4% less than in 2017 and the first significant reduction after four years of stagnation. The Federal Environment Agency indicated that the drop in emissions is largely due to unusual weather conditions in 2018 leading, for instance, to higher renewable energy generation than in an average year and a declining consumption of fossil fuels (Umweltbundesamt, 2019a). Our analysis shows that absolute emission levels resulting from current policy trajectories and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic will be at 714-734 MtCO2e in 2020, which is 41-43% below 1990 excl. LULUCF. This figure has to be viewed carefully as it assumes that the emissions are scaled downwards, with the fall in GDP. Only the actual figures will tell whether the targets will be achieved due to temporary emission reductions caused by the pandemic.

For our analysis we used two scenarios to project future emissions pre-COVID19: one based on the updated reference case of the projection report (“Projektionsbericht”) published by the Federal Environment Agency in March 2020, which only includes measures that were implemented by 29 January 2020 (German Federal Environment Agency, 2020). The other scenario, published on behalf of the German Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi) in March 2020, also quantifies the measures included in the Climate Action Programme (Kemmler et al., 2020). We harmonise both scenarios to the latest available historical data and use the updated lower emissions value for 2019 (805 MtCO2e) published by the Federal Environment Agency (Federal Environment Agency, 2020). Both scenarios lead to emissions reductions in 2030 of between 41% (Federal Environment Agency) and 53% (BMWi) below 1990 levels, still not sufficient to meet Germany’s 55% reduction target. Taking into account the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (see below for method), we estimate that emissions could be reduced by 47% - 55% below 1990 levels in 2030.

The emissions trajectory will be strongly dependent on the speed and character of the post-pandemic economic recovery. In June 2020, the German government agreed a €130 billion stimulus package. Along with more general measures such as a VAT reduction for the second half of 2020 and other tax rebates, it includes a €50 billion “package for the future” that contains investments into climate-friendly technologies and mobility (German Government, 2020b). While the overall focus on climate-friendly technologies was welcomed, NGOs criticised that the government missed the opportunity to fully align the programme with its climate targets (Wehrmann and Wettengel, 2020).

In September 2019 the “Klimakabinett”, a committee including chancellor Angela Merkel and the Ministers of Environment, Agriculture, Finance, Economy, Building and Transport, agreed on a Climate Action Programme for 2030 including a package of sectoral measures and sectoral targets for emission reductions (German Government, 2019c). Germany adopted the package as national climate law and associated regulations in December 2019. The package received heavy criticism from experts and NGOs (Enkhardt, 2019b).

The package distributes the 55% emissions reduction target by 2030 to sectors and gives responsibility to sectoral ministries to implement it. The Building and Transport ministries would also be responsible for paying the fines due under the EU Effort Sharing Regulation, if these targets were not met. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, such a penalty for Germany was estimated in the order of €60 billion if no additional measures were implemented (Agora Energiewende and Agora Verkehrswende, 2018; Höhne and Fekete, 2019).

The law includes binding sectoral reduction targets and the appointment of an expert commission that verifies the annually calculated emissions projections of the Federal Environment Agency, including its sector allocation. If the expert commission finds that a sector is missing its target, the responsible ministry has to submit an emergency programme within three months.

Energy supply

According to the German government targets proposed in the Climate Action Programme and legislatively anchored in the climate law, the energy sector will have to limit its GHG emissions to 175 MtCO2e by 2030. This is a reduction of 62 % below 1990 levels. The Climate Action Programme states that by 2050, energy supply must be “almost” completely decarbonised. On a positive note, the energy sector has already reached its target for 2020 (280 MtCO2e) in 2019 (254 MtCO2e) (German Ministry of Environment, 2020). A driver of this reduction is a significant increase in the share of renewable energy in the electricity mix, but primarily the production of existing capacity increased due to particularly windy and sunny weather, not so much the expansion of renewable capacity (German Ministry of Environment, 2020). Still, the relatively slow and gradual coal-phase out by 2038 and difficulties with the expansion of renewable energy capacity pose a risk to Germany’s ability to reach its longer-term targets for 2030 and 2050.

Implementing all measures proposed in the Climate Action Programme would lead to a remaining 183 - 186 MtCO2e by 2030, leaving a gap of between 8 - 11 MtCO2e (German Federal Environment Agency, 2020; Kemmler et al., 2020). These figures do not take into account the potential impact of COVID-19. As a result of the pandemic, electricity consumption dropped from 246 TWh in the first half of 2019 to 234 TWh in the first half of 2020 (Fraunhofer ISE, 2020a; IEA, 2020). How much this will affect the 2030 target will depend on how strong electricity consumption will rebound in the ten years between 2020 and 2030. During the financial crisis in 2009, for instance, electricity consumption completely rebounded just one year after the crisis.

Coal phase-out

Although CO2 emissions from lignite and hard coal have declined in recent years, about one fifth of total German CO2 emissions still comes from power and heat generation from coal-fired power plants (Agora Energiewende, 2020a).

In January 2019, a government-appointed, multi-stakeholder “coal commission” developed a compromise for phasing out coal-fired power generation in Germany (Kommission „Wachstum Strukturwandel und Beschäftigung“, 2019). The commission proposed phasing out coal by 2038 at the latest and to shut down 13 GW of the currently 43 GW of installed coal capacity by 2022, an additional 13 GW by 2030 and phasing out all production by 2038, with an option of bringing this date forward to 2035.

The original coal compromise was reached with broad societal consensus, but the schedule is not fast enough to be compatible with 1.5°C. In Paris Agreement-compatible pathways for OECD countries, coal power generation would need to be reduced by 86% by 2030 below 2010 levels, leading to a phase-out by 2031 (Yanguas Parra et al., 2019). And while the government promised to enshrine the coal exit roadmap into law by November 2019, it did not adopt it until July 2020, and significantly watered it down from the original compromise; heavily criticised by environmental organisations, scientists, former members of the coal commission as well as the independent expert commission advising the German government on energy issues (Deutscher Bundestag, 2020; DIW, 2020; Löschel et al., 2020). Several studies show that a faster coal phase-out by 2030 would be possible (Oei et al. 2019, Kittel et al. 2020, Oei et al. 2020c).

The coal exit law deviates in several points from the original compromise – at the expenses of climate protection. The changes include dropping substantial CO2 reductions for the period up to 2025 and, in the particularly relevant period from 2023, the phase-out no longer takes place continuously but concentrates on the years 2028-2029 to meet the set target for 2030 (Praetorius et al., 2020).

Further, the coal exit law allows an exception for the ban on building new coal-fired power plants (German Government, 2020c). The text states that the ban does not apply to plants for which "an emission protection permit had already been granted by the time the law enters into force". As a result, the controversial 1,100 MW Datteln 4 coal-fired power plant went online in May 2020 (German Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, 2020). This violates one of the principles of the Powering Past Coal Alliance, which Germany joined in 2019, agreeing to prohibit the construction of new coal-fired power plants (DIW, 2020).

Projections show that coal-fired power plants operating as planned under the German coal exit law would emit almost 2 GtCO2e cumulatively between 2030 - 2038 (DIW, 2020). This is roughly half of Germany’s carbon budget under the CAT’s estimation of Germany’s “fair share” contribution towards limiting global warming to 1.5°C. Further, the compromise was found only by compensating the affected regions (€40 billion and the affected companies operating the coal-fired power plants (additional €4.35 billion) (Agora Energiewende, 2019; Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie, 2019). Research shows the German government is overcompensating the coal companies by almost €2 billion when comparing the difference between a generous, rule-based compensation and the actual proposed lump-sum compensation (Matthes et al., 2020). Coal-fired powerplants will probably not be economically viable in the short run anyway, due to increased prices of CO2-certificates, which increased already in the first half of 2020 and which are expected to further increase in the context of the European Green Deal (Fraunhofer ISE, 2020b; Matthes et al., 2020).

Renewables

The share of renewables in German net electricity generation rose from 40.6% in 2018 to 46% in 2019, surpassing the share from fossil fuels (40%) for the first time and reaching a record share of 55.8% in German net electricity generation in the first half of 2020 (Fraunhofer ISE, 2020c). However this is mainly due to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as numerous winter storms that have increased the share of wind power, while capacity additions for all major technologies have declined (Fraunhofer ISE, 2020b).

After the end of the solar boom from 2010-2012 that saw more than 7.5 GW of additions per year, installation rates fell to 1 GW in 2014 (AGEE, 2019), which saw approximately 100,000 jobs lost (Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie, 2018). In 2019, solar installations underwent a significant increase with almost 4 GW of newly installed capacity while less than 1 GW was added in the first half of 2020 (Fraunhofer ISE, 2020a).

Offshore wind installations peaked at 2 GW in 2015 and were at 1.1 GW in 2019; onshore wind installations peaked at 5 GW in 2017, have significantly dropped in 2019 (0.92 GW) and only very slightly picked up again in the first half of 2020 (Appunn, 2020; Fraunhofer ISE, 2020a). A change in the auctioning system and delays in issuing permits led to a delay in construction of auctioned amounts. As a consequence, wind companies are in serious economic trouble, losing approximately 20,000 jobs from 2016 to 2017, and the outlook is grim (Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie, 2018). Wind giant Enercon alone had lost around 3,000 jobs by November 2019 (Balser and Bauchmüller, 2019).

The German government aims to raise the share of electricity generated from renewable energy to 65% of gross electricity consumption by 2030. While the quantifications of the Climate Action Programme 2030 suggest the target is likely to be met (61-65% in 2030), the government has not implemented sufficient measures to reach this target which itself is not enough, given the relative ease with which emissions can be reduced through renewable energy compared to other sectors (German Federal Environment Agency, 2020; Kemmler et al., 2020). Other studies have estimated onshore wind installations would need to increase to at least 4.4 GW and solar PV to at least 4.3 GW a year to reach the target (Oei et al., 2019). A recent study shows that currently implemented measures would only lead to a 46% share of renewable electricity generation in 2030 (EWI, 2020).

The Climate Action Programme increased the expansion targets for 2030 for offshore wind to 20 GW, onshore wind to 67-71 GW and solar PV to 98 GW. These installation targets imply average annual capacity additions of 4.8 GW for solar PV, and 1.3-1.7 GW for onshore wind. The support cap of 52 GW for PV was removed completely. In 2020, the government agreed the minimum distance regulations to settlements for wind turbines will be subject to individual decisions by the federal states. While this is a step into the right direction, if the states all adopt the national government’s attitude, this could drastically reduce space for wind turbines, making it difficult to reach annual capacity additions of 1.3-1.7 GW for onshore wind (German Federal Environment Agency, 2020; Umweltbundesamt, 2019b).

In June 2020, Germany released its National Hydrogen Strategy (German Government, 2020d) that focuses on “green” hydrogen produced by using renewable energy, and sets out 38 measures for the period up to 2024 to support hydrogen production and to identify fields of application (German Government, 2020d). The government hopes to establish hydrogen as an alternative energy carrier to enable the decarbonisation of hard-to-abate sectors, like industry and aviation (Amelang, 2020). In addition to existing government programmes, the COVID-19 stimulus package includes a further €9 billion investment into supporting the technology development and hydrogen production in both Germany and partner countries, and to support a switch in industry processes.

Industry

Industry emissions declined by 30% from 1990 to 2008 and have been stable since. However, emissions still need to be reduced by 48 MtCO2e to meet the sectoral target of 140 MtCO2e/year by 2030. The measures introduced in the Climate Action Programme would lead to a level of 143 MtCO2e/year by 2030, leaving a gap of 3 MtCO2e (German Federal Environment Agency, 2020; Kemmler et al., 2020).The main instrument for emissions reductions, the EU ETS, has not led to reductions due to the low CO2 price and over-allocation of certificates in the sector.

The Climate Action Programme includes several measures focusing on the improvement of energy efficiency and proposes streamlining the existing support programmes into a "one-stop-shop" and promises additional support from low carbon technologies in areas where reductions are difficult - without any detail of the level of available funding (German Government, 2019c). While these are steps in the right direction, many sectoral measures have not yet been developed in detail, and their impact is therefore difficult to predict.

In April 2020, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, industrial production decreased by 25% compared to the previous year - the largest decrease on record (Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis), 2020). The automobile industry recorded a particularly sharp 74.6% decline. Research suggests the COVID-19 pandemic could potentially reduce emissions in the industry sector by 10 – 25 MtCO2e in 2020 compared to the previous year (Agora, 2020).

Transport

According to German government targets, transport sector emissions need to be reduced by 42% below 1990 levels, meaning they would have to fall to no more than 95 MtCO2e in 2030, while, at 162 MtCO2e in 2019, they are still at 1990 levels today. Measures adopted in 2019 will reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 13 MtCO2e, leaving a gap of 52 to 55 MtCO2e over the next decade (Federal Environment Agency, 2020). This is the largest gap of all sectors in Germany. To close this gap the German Government proposed several measures in its Climate Action Programme that would lead to emissions of between 125 and 128.4 MtO2e in 2030, still leaving a gap of 30 to 33.4 MtO2e/year (German Federal Environment Agency, 2020; Kemmler et al., 2020). Research suggests that due to the COVID-19 pandemic emissions in the transport sector could potentially be reduced by 7 – 25 MtCO2e in 2020 compared to the previous year but are expected to bounce back as mobility restrictions are lifted (Agora Energiewende, 2020b).

Passenger vehicles

In Germany registrations of new passenger cars were down by 35% over the first five months of 2020, a slightly less severe drop than the EU average (41.5%). The registrations of alternatively powered vehicles increased by 74% in the first quarter of 2020 compared to 2019 due to the financial incentives introduced by the German government and in the first half of 2020 the share of electric vehicles in total registrations was at a record high of 7.4% (ACEA, 2020).

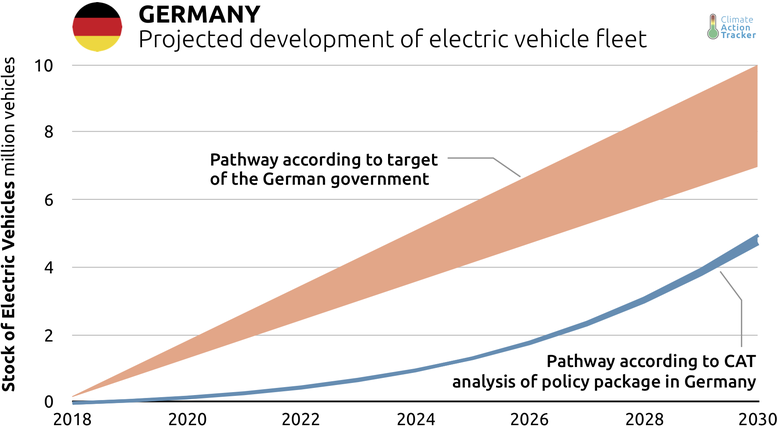

The German government has set a goal of seven to ten million electric vehicles in its fleet by 2030. By November 2019 only 220,000 were on the road (VDA, 2019). To reach this target the government has prolonged tax credits for company cars with batteries or plug-in-hybrid vehicles until 2030 and reduced the taxes for pure electric company cars up to a price of €40,000 from 0.5% to 0.25% (German Government, 2019c). In 2019, the government agreed with the German car industry to increase the financial incentive for newly purchased battery electric vehicles (BEVs) from €3,000 to €6,000 (€3,000 from the Government and €3,000 from manufacturers). The incentive was also expanded to cover vehicles above €40,000, which were previously not eligible. However, the premium may lead to hidden price increases given half of it is covered by the producers themselves. Small start-ups cannot cross-subsidise this premium from other business and may need to raise the price of the EVs, potentially cutting the effective premium in half. As part of the COVID-19 stimulus package ,the government has decided to exempt EVs from vehicle tax until 2030 and has doubled the state’s share of the buyer’s premium for EVs until the end of 2021 from €3,000 to €6,000(German Government, 2020b).

The stimulus package also introduced a €2 billion programme for investments into new technologies by car manufacturers, and another €2.5 billion for expanding EV charging infrastructure and supporting electric mobility research. It should be noted that the government refrained from any form of premiums for cars with combustion engines, despite the intense pressure from German industry (DW, 2020).

With 27,730 chargers by March 2020, the Government aims to have 50,000 public charging stations by the end of 2020 (BDEW, 2020; German Government, 2019c). The Climate Action Programme also stipulates that the number of public charging points for electric vehicles should increase to one million by 2030. All petrol stations will be required to have EV charging stations and if the set goal cannot be achieved through market mechanisms, the government is considering further regulatory measures. On a per capita level, this would result in 604 chargers/million people in 2030, still significantly lower than Norway today, where there are 2,364 public chargers/million people (IEA, 2019).

Initial results from our own modelling1 suggest that the current support of €6,000 per vehicle (€9,000 until 2021), together with the rest of the policy package already in place in Germany, would lead to an uptake of EVs of approximately five million by 2030, well below the target of 7– 10 million (approx. 30% - 50%) by 2030. This would correspond to a share of 30% of EVs in the cars sold in 2030, which is not in line with the Paris Agreement-compatible target of the last fossil fuel car sold by 2035 and is in stark contrast to Norway’s announcement of aiming to have all new cars be zero emission vehicles by 2025.

1 | We compare the support provided for EVs with that in Norway and the corresponding development in the shares of EVs (De Villafranca Casas et al., 2018).

Public transport

The government plans to increase its budget for the improvement and expansion of the public transport system to €1 billion per year from 2021 and €2 billion from 2025. Deutsche Bahn, the national rail company, and the government further plan to invest €86 billion into the rail network by 2030. Additional measures include the reduction of the value added tax from 19% to 7% on long-distance tickets from January 2020 and the support of model projects, including an annual public transport ticket for €365 (German Government, 2019c).

The impact of these measures is difficult to quantify but it can be assumed that they will contribute to emissions reductions and modal shift. As part of the COVID-19 recovery package the government has pledged to provide additional financial support for public transport in the order of €2.5 billion to municipalities and to inject further €5 billion into Deutsche Bahn for railway modernisation, expansion and electrification, despite lockdown-related income losses (CarbonBrief, 2020; German Government, 2020b).

The overall Climate Action Programme also includes the increase of the tax credit for long distance travel to work (‘Pendlerpauschale’). It was introduced to dampen the burden of the CO2 price for commuters, but also makes long distance commuting by car more attractive, i.e. leads to increased emissions.

Carbon price

As of 2021 emissions trading will be introduced on transport fuels. Certificates will be distributed for a fixed price of €25/tCO2 in 2021 rising to €55/tCO2 in 2025 (previously proposed to be at 10€ and 35€ respectively). After 2025 new allowances will be auctioned in a corridor of €55 to €65/tCO2 (German Government, 2020a). If more allowances are needed than available, additional allowances can be purchased from other EU member states. Hence the effectiveness of the instruments also depends on the stringency of measures in other member states.

The impact of this new system is very difficult to predict. An initial price of €25/tCO2 will only have limited effect. If demand supersedes the amount that is provided at a fixed price and allowances need to be purchased from member states, this could see prices reaching relatively high levels. All proceeds from the pricing system will be re-invested into climate protection or returned to citizens.

Aviation

To avoid airlines from offering low ticket prices (“dumping prices”), the Climate Action Programme stipulates that tickets must not be cheaper than the costs of taxes, surcharges and other fees combined and the German government plans to increase the aviation levy by April 2020 and almost double taxes on short-haul flights. For flights up to 2,500 km the levy will be increased from €7.50 to €13.03, from 2,500 – 6,000 km from €23.43 to €33.01 and for flights above 6,000 km from €42.18 to €59.43 (German Federal Ministry of Finance, 2019). Compared to the UK where the levy for flights above 2,000 km is €83.35, this is still quite low.

The COVIC-19 pandemic caused passenger flights to drop by 93% in April 2020, compared to the previous year, and they were still down by 76% in the end of June (OAG, 2020). It is likely that the sector will bounce back quickly once the pandemic is over.

In May 2020, the German government agreed on a €9 billion rescue package for the largest German airline Lufthansa. In sharp contrast to bailout packages by other European countries, this bailout is disappointingly not attached to any additional environmental requirements(Wilkes, 2020). As part of the COVID-19 stimulus package the government has put forward €1 billion for modernising aviation, accelerating a shift towards more efficient aircraft fleets., and another billion for modernising shipping (German Government, 2020b).

Buildings

The buildings sector is responsible for 14% of Germany's total emissions. Emissions have declined by 23% from 2009-2019 and still need to reduce further to meet the sectoral target of 70 MtCO2e/year by 2030. The measures introduced in the Climate Action Programme would only lead to a level of 78 - 87 MtCO2e/year by 2030, leaving a gap of 8 to 17 MtCO2e (German Federal Environment Agency, 2020; Kemmler et al., 2020).

Carbon price

As of 2021 emissions trading will be introduced on fuels in the buildings sector. Certificates will be distributed for a fixed price of €25 /tCO2 in 2021 rising to €55 /tCO2 in 2025. After that, new allowances will be auctioned in a corridor of €55 to €65 /tCO2 (German Government, 2020a). If more allowances are needed than available, additional allowances can be purchased from other EU member states. All proceeds from the pricing system will be re-invested into climate protection or returned to citizens. To ensure that the costs of climate protection do not put a burden on people with low incomes, housing allowances are planned to increase by ten percent from January 2021 onwards (German Government, 2019c).

The impact of this new system is very difficult to predict. An initial price of €25 /tCO2 will only have limited effect. In the long term, prices could reach quite high levels, if demand superseded the amount that is provided at a fixed price, but again, this is difficult to predict.

Building renovations

Germany has a long tradition in providing low interest loans for renovation of buildings and support of renewable heating systems, especially for new buildings. As part of the COVID-19 recovery package the German government is providing an additional €2 billion for energy-efficient renovations of buildings (German Government, 2020b).

As a new measure of the Climate Action Programme, energy-efficient retrofits of buildings used by the owner become tax-deductible by 2020. In addition, a scrap premium of 40% is paid on exchanging an oil heating system by a new one based on renewables or gas with a share of renewables.

According to the programme, new oil heating systems will be forbidden as of 2026, but existing systems can still be operated after this date. This measure does not appear ambitious, as for example the Netherlands already today require that new buildings cannot use fossil fuel heating systems, not even gas (EnergyPost, 2017).

Agriculture

Since 1995 emissions from the agriculture sector have remained almost unchanged. The sectoral target for the agriculture sector is to emit no more than 58 MtCO2e/year by 2030. Compared to 2018, emissions would have to be reduced by 9%, or by 6 MtCO2e by 2030 (Umweltbundesamt, 2019c). With the measures introduced in the Climate Action Programme, the level is expected to still stand at 64 MtCO2e in 2030, leading to a gap of approximately 6 MtCO2e/year.

In April 2019, the Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture developed a ten-point plan to decrease emissions in the agriculture sector, including the calculation of the yearly mitigation potential showing an emissions reduction potential of between 12.5 – 30.1 MtCO2e/year (Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft, 2019). However, only the first five points relate to agriculture, while the others are related to LULUCF. The mitigation potential of the agriculture measures only equates to 5.5 – 13.6 MtCO2e/year, which may not even be enough to reach the minimum target.

Overall, the plan proposes the expansion of organic farming which would constitute 20% of all farming by 2030 through increased financial support and emission reductions from livestock farming in line with animal protection. Further, nitrogen surpluses are expected to be decreased with new regulations for the use of fertilisers, and a national strategy for the avoidance of food waste will be developed. Moor and peatlands will receive better protection and overall, the capacity of soils as carbon sinks will be better exploited, e.g. through reducing the use of peat in growing media.

Forestry

Forests cover approximately 11.4 million hectares in Germany, which equates to one third of Germany's national territory. The LULUCF sector has been a net sink of CO2 emissions. However, in 2017, the removal of CO2e has more than halved compared to 1990 (15 MtCO2e compared to 31 MtCO2e) while forests are increasingly suffering from the impacts of climate change. Even with the measures introduced in the Climate Action Programme, the sector would turn into a net emissions source and emit 16.3 MtCO2e/year by 2030, clearly missing the target of zero by 2030 (German Federal Environment Agency, 2020).

Measures proposed in the Climate Action Programme include increasing efforts for reforestation and the adaptation of forests to changing weather patterns, increasing the capacity of soils as carbon sinks and better protection of moors and wetlands, in a general effort to make carbon sinks more resilient to extreme weather events (German Government, 2019c). The COVID-19 recovery package includes an additional €700 million for the conservation and sustainable management of forests (German Government, 2020b).

The Forest Strategy 2020, which was adopted in 2011, aims to coordinate the ecological, economic and social demands on forests in Germany. One objective of the Strategy is to utilise forest management and wood use to contribute to reducing CO2 emissions and conserve German forests to enhance their resilience (German Federal Ministry of Food Agriculture and Consumer Protection, 2011).

Waste

In 1990 the German waste sector still emitted 38 MtCO2e (3% of total emissions). By 2018, emissions were at 10 MtCO2e - a decrease of 74% and contributing only about 1% of total emissions. This was achieved mainly by ending the disposal of untreated residential waste and the increased utilisation of energy and materials from waste (Umweltbundesamt, 2017). Since 2005 landfilling of biodegradable waste is prohibited in Germany.

The Climate Action Programme proposes three additional measures for the waste sector: 1) continued support of small landfill aeration projects, 2) additional support for large landfill aeration projects and 3) optimised landfill gas capture (German Government, 2019c). If these measures were to be implemented emissions in the sector would reach 4.9-5 MtCO2e in 2030 meeting the sectoral target of 5 MtCO2e set in the climate law.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter