Country summary

Overview

Indonesia is one of the most populous countries in the world, with substantial emissions from forestry, increasing emissions in all sectors, and a massive coal-fired power generation pipeline; it is also highly vulnerable to climate change. Indonesia’s 2030 NDC target is rated as “Highly Insufficient”; however, its current policy projections, if rated, are better (“Insufficient”” and show modest signs of improvement). As with many countries, coal remains a serious and growing issue in Indonesia with plans to install over 6 GW of coal-fired power generation by 2020 and about 27 GW by 2028. Shifting the investments in coal planned for the next five years towards renewable, zero-carbon solutions is crucial to put Indonesia on a pathway compatible with the Paris Agreement and sustainable development.

Indonesia’s current policy emissions projections have been revised downwards, in part due to reduced energy demand expectations. The government has published its medium-term development plan (RPJMN) covering the period between 2020 and 2024. The RPJMN sets a more ambitious renewable electricity target which projects an increase in renewable capacity over three times higher between 2020 and 2024 than anticipated in the electricity supply plan published early in January. If fully implemented, the RPJMN could result emissions reductions beyond current policies and even beyond the National Energy Policy, which sets a renewable target of 23% in total primary energy supply by 2025. But there are no policies in place to support such targets and it is uncertain to what extent Indonesia will adjust existing plans to reach them.

In the past, the government has implemented some policies to support reaching its renewables targets, e.g. by regulating the installation of rooftop solar. However, various design elements of these policies and the general investment environment still favour large-scale fossil-fuelled power and prevent a swift and large-scale expansion of renewables.

In light of the increasing concerns about air pollution, Indonesia is shifting its attention towards electric vehicles (EVs). In 2019, the government implemented supportive policies that aim to not only increase the number of EVs and charging stations but also to develop the country’s local EV manufacturing industry. But, to harness the benefits of EVs for climate, the uptake of vehicles needs to be coupled with decarbonising the electricity sector.

Based on current policy projections, Indonesia is very likely going to overachieve its Paris Agreement targets excluding the forestry sector. However, the CAT rates the Indonesian NDC target (excluding forestry) as “Highly insufficient”. This overachievement puts Indonesia in a position to significantly increase the ambition of its NDC. Including the 2025 renewable energy target in the updated NDC is the first step, though further action would be needed to become 1.5°C compatible.

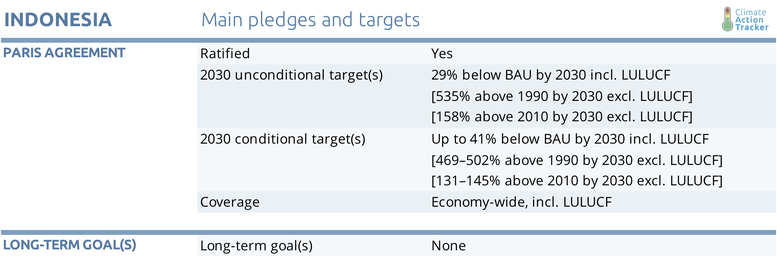

With international support, Indonesia pledges to achieve a 41% reduction from BAU in 2030 (roughly equivalent to doubling of today’s emissions levels). See the pledges and targets section for details and analysis.

While Indonesia’s relative reductions below BAU anchored in its NDC may sound ambitious, a second look reveals a different picture for two reasons: first, Indonesia aims to meet a large share of its commitments through reductions in the forestry sector. This means that other sectors will see substantially lower relative reductions of emissions below BAU. Second, the BAU for the targets projects an increase substantially above our projections under current policies. In fact, Indonesia will achieve its targets (excl. forestry) without any additional efforts while still doubling today’s emissions.

The CAT rates Indonesia NDC excl. the forestry sector as “Highly insufficient” (see Fair Share section). Indonesia’s NDC could be easily strengthened by ensuring its existing renewable energy targets are met. Indonesia’s National Energy Policy (NEP) has a target to increase renewable energy to 23% of total primary energy supply (TPES) by 2025 and 31% by 2050. The new medium-term development plan states that renewable power generation will reach almost 40 GW by 2024, up from 9.5 GW at the end of 2018. If Indonesia were to meet these targets, it would overachieve both its unconditional and conditional NDC targets to an even greater extent than already envisaged.

Indonesia works on five-year planning cycles. It has published its next five-year plan, covering 2020-2024, which foresees an increase in renewable power capacity over three times higher than the electricity supply plan from early 2019 (Ministry of National Development Planning (Bappenas), 2019).

Also in 2019, the Ministry of National Development Planning (BAPPENAS) released its low-carbon development plan, containing three long-term (2045) emission pathways. Only one of these long-term scenarios would bend GHG emissions downwards by 2045, halving emissions (including forestry) compared to today’s levels. While the CAT does not include the forestry sector in its analysis, an increase in total emissions up to 2050 is not in line with any “fair” interpretation of a 1.5°C Paris Agreement compatible development pathway.

A further governmental study for the medium term plan, released in August 2019, appears to only contain the ‘moderate scenario’, now referred to as the ‘fair’ scenario (Kementerian PPN/Bappenas, 2019). Under the ‘fair’ scenario, GHG emissions would be 27.3% below BAU in 2024. This scenario appears to be consistent with the current unconditional NDC and would not be consistent with low carbon development (Climate Action Tracker, 2019).

For electricity generation, hydro remains the biggest source of renewable electricity, reaching a total installed capacity of approximately 5.5 GW at the end of 2018, followed by geothermal and bioenergy with almost 2.0 GW each. Solar and wind reached together 137 MW with the opening of the 75 MW country’s first wind farm (Sidrap) in 2018. The total renewable installed capacity in 2018 reached 9.5 GW at the end of 2018, well below the government target of 15.5 GW for the same year.

The transport sector has also seen progress in the past year. In March 2019, the first line of Jakarta’s Mass Rapid Transit system opened. The government also issued a regulation aiming to boost domestic electricity vehicle (EV) manufacturing and reach electric vehicle targets.

Indonesia’s biofuel blending mandate is one of the most ambitious in the world. Since 2016, the electricity sector must have 30% of its energy supplied by biofuels. However, while Indonesia’s biofuels targets are ambitious, they are not without controversy due to concerns with palm oil production: plantations for biofuel production are specifically exempt from a key sustainability certification.

Since 2011, the government has a had palm-oil moratorium on new palm oil plantations in an area of 66 million hectares. This moratorium has been renewed, but recently the president issued a presidential instruction making it permanent (Diela, 2019). The efficacy of the moratorium has been ambiguous: while the policy is considered to be a good instrument to limit future deforestation in Indonesia, some research shows that deforestation has increased since its implementation due to lack of proper enforcement.

The issue of forest clearance for palm oil is a major problem in Indonesia, which alone contributed to 7% of the total global tree cover loss between 2001 and 2018 and contributes to a large share of Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) emissions reaching around 1 GtCO2e/year – due to an unusually high occurrence of peat fires, the emissions from the LULUCF sector in Indonesia reached 1.6 GtCO2 in 2015. To put that into context, global emissions from LULUCF were about 4.1 GtCO2e in 2016.

In 2019, the Indonesian fires have again been a special source of concerns: in the week of 13 September alone, there were more than 70,000 fire alerts across the country (Global Forest Watch, 2019) causing a state of emergency in at least six Indonesian provinces and sparking complaints from neighbouring countries that were affected by the toxic haze.

Further analysis

Country-related publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter