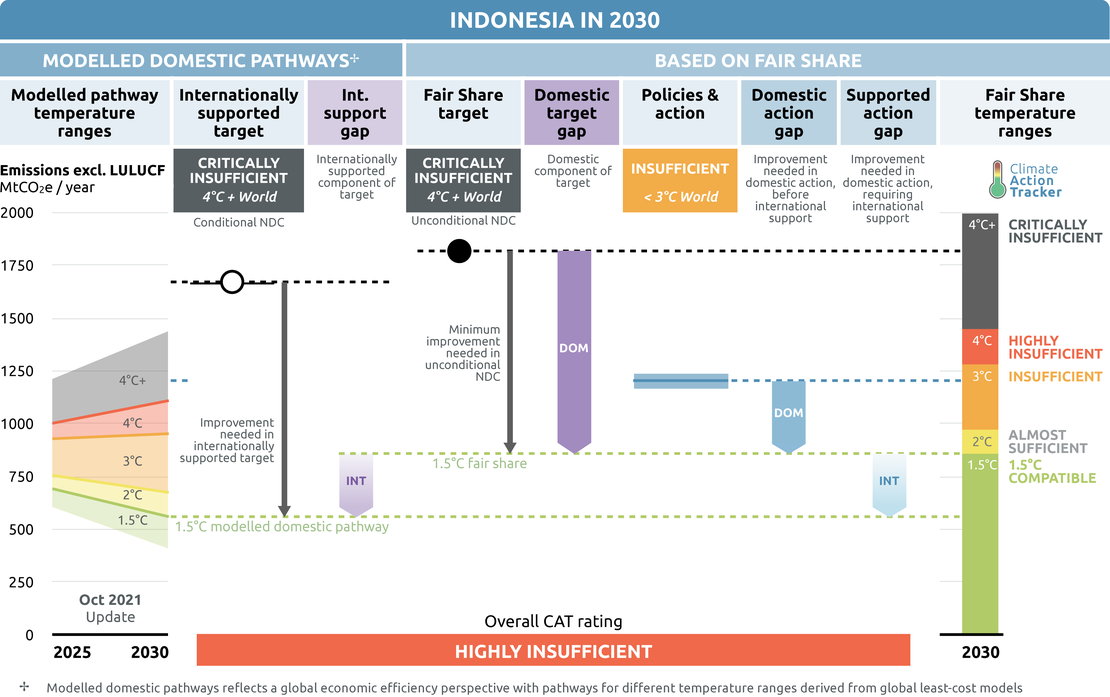

Policies & action

We rate Indonesia’s policies and action as “Insufficient” compared to their fair share contribution. The projected emissions under current policies fall in the upper half of the “Insufficient” range. Indonesia is expected to implement additional policies with its own resources but will also need international support to implement policies for a full decarbonisation. The “Insufficient” rating indicates that Indonesia’s climate policies and action in 2030 need substantial improvements to be consistent with the 1.5°C temperature limit. If all countries were to follow Indonesia’s approach, warming would reach over 2°C and up to 3°C.

Recent developments and plans confirm that Indonesia plans to lock-in long-term dependency on coal. Since 2010 Indonesia has commissioned around 23 GW of coal power capacity and by the end of 2020 had a further 11 GW under construction – amounts exceeded only by China and India (Global Energy Monitor et al. 2021).

The new plan for the electricity sector (RUPTL) fails to envisage a shift away from coal-fired power, which accounts for around 14 GW of the planned added capacity between 2021 and 2030 and is set to meet 64% of demand in 2030. Indonesia’s ambitious low carbon (LCCP) scenario also foresees a significant role for coal – amounting to around 58% of the power mix in 2030 and 38% by 2050. These plans are not aligned with the goals of the Paris Agreement, for which Indonesia would need to reduce the share of coal-fired power generation to a maximum of 10% by 2030 and phase out coal by 2040 (Climate Action Tracker 2020b).

Renewables development has been slow, and current plans do not make full use of Indonesia’s renewable energy potential. Renewables accounted for just 11% of added power capacity between 2019 and 2020, while the installed capacity in 2020 fell short of the targets set by the national energy plan (RUEN) – hydropower and geothermal reached 80% of these targets, while solar, bioenergy, and other renewables reached just 8%, 5%, and 4% of these targets, respectfully (Republic of Indonesia 2021). The new RUPTL did not increase Indonesia’s renewable energy target, which remains at 23% by 2030.

The utilisation of renewable energy potentials is currently very low, ranging from just 0.03% for solar power to 5% for hydropower. The recent record-low bids for renewables like floating solar PV (3.68 USDc/kWh) show that these technologies are already competitive in the Indonesian context (IESR 2021e). However, to realise the full potential outlined above, the government must address the many barriers facing renewable energy development (IESR 2021d).

Indonesia’s biofuel mandate is one of the most ambitious in the world. Indonesia has plans to increase the national energy consumption mandate to 40% in 2022 and produce biodiesel solely from palm oil (IESR 2021e). However, while Indonesia’s biofuels targets are ambitious, they are controversial due to the environmental concerns with increased palm oil production, and deforestation.

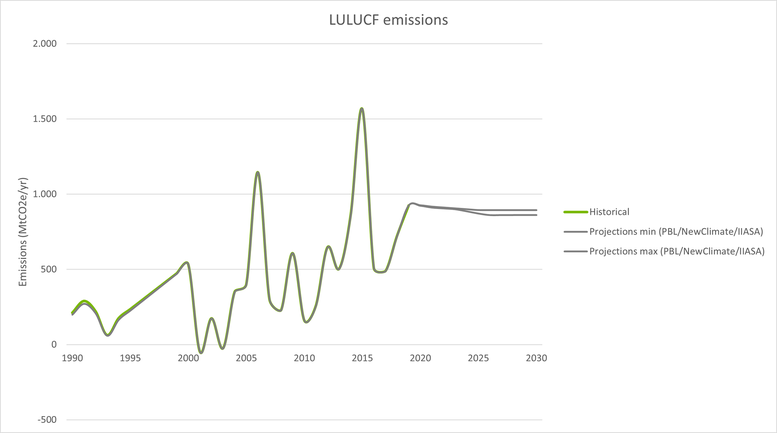

The LULUCF sector contributes a large share of emissions reaching around 1 GtCO2e/a. Mitigation measures in the forestry sector, particularly the moratorium on new forest clearance for activities such as palm oil plantations or logging, have helped Indonesia to reduce tree cover loss since 2016, however, commodity-driven deforestation is still a major concern, accounting for over 90% of forest cover loss in 2019 (Global Forest Watch 2021). Forest clearance for palm oil alone accounted for 7% of total global tree cover loss between 2001 and 2018. The plans for the forestry sector to be a net sink by 2030, outlined in Indonesia’s LTS, rely on the expansion and effective enforcement of existing measures (Reuters 2021).

In March 2019, the first line of Jakarta’s Mass Rapid Transit system opened, allowing a shift from private to public modes of transportation in the city. The government also issued a regulation aiming to boost domestic electricity vehicle (EV) manufacturing and increase EV shares, but details still need to be further defined to harness the EV mitigation potential.

Policy overview

The CAT estimates that Indonesia’s emissions (total excl. LULUCF) dropped by 5% in 2020 due to the lower economic activity and under current policies will reach 1,167–1,240 MtCO2e/a in 2030 (excl. LULUCF). Under current policies, Indonesia overachieves its unconditional NDC and conditional 2030 targets (excl. forestry), despite strongly increasing emissions and not achieving other national targets, e.g., the National Energy Policy, or NDC reductions for LULUCF emissions.

In 2019, Indonesia published its RPJMN 2020-2024 medium term plan, which includes strategies and targets that will guide the country’s development for the next five years (Ministry of National Development Planning (Bappenas) 2019). The RPJMN, used as the lower range of our planned policies projections, could lead to emissions of 1,070 MtCO2e/a excl. LULUCF in 2030, down from 1,222 MtCO2e/a in our previous pre-COVID assessment.

The full effect of COVID-19 on emissions is subject to much uncertainty as emissions projections are dependent on the economic impacts as well as the recovery measures.

The government allocated approximately USD 48bn in 2020 and 2021 (IDR 700 tn) to fund the National Economic Recovery (Ministry of Finance Indonesia 2020a). It does so with the establishment of numerous policy instruments such as tax incentives, direct investments and subsidies, and loans (Cabinet Secretariat of the Republic of Indonesia 2020; Ministry of Finance Indonesia 2020b; Media Indonesia 2020). The post-COVID-19 economic recovery presents an opportunity to increase investment in low-carbon development, especially to foster renewable energy development (Amri, Roesad, and Damuri 2020; Sumarno and Sanchez 2021; IESR 2020). Greening recovery packages can reduce air pollution, create more and better jobs, lead to a more resilient and independent energy supply, and enhance access to energy (Climate Action Tracker 2020a).

In 2020, at least USD 7.5 bn (IDR 109 tn) went to supporting different energy types through new and amended policies, representing around 16% of the government’s total recovery budget (Ministry of Finance 2021; Sumarno and Sanchez 2021). The government failed to trigger a strong green recovery in its economic stimulus, allocating just 3.5% of the total budget to clean energy development (Energy Policy Tracker 2020; IESR 2021e). The COVID-19 recovery packages more than double the existing subsidies to fossil fuels, amounting to almost USD 7bn in 2020 (IDR 97tn), covering electricity (51%), LPG (34%), and fuel (15%), equal to around 8% of the national budget in 2020 (IESR 2021e). By mid-2021 the OECD and IEA estimate that fossil fuel subsidies announced during the pandemic reached USD 12-13 billion (OECD/IEA 2021).

Amidst lower domestic and export demand for coal, the government capped the price of domestic coal at USD 20 per tonne below market value to boost consumption in 2020 (Harsono 2020) and in 2021 moves forward with plans to develop Indonesia’s downstream coal industry, despite the risks of stranded assets (IESR 2021b).

Recent policies to foster renewables development have not been so successful, but some steps have been taken to improve their effect, such as the removal of the obligatory ‘build, own, operate, and transfer’ (BOOT) scheme in the second amendment to MEMR Regulation 50/2017 (MEMR 4/2020). However, policies to support low-carbon development in Indonesia need adjusting to realise their full mitigation potential. Some design elements of policies supporting the uptake of renewables and the general investment environment still favour large-scale, fossil-fuelled power and prevent a swift and large-scale expansion of renewables.

Indonesia’s biofuel future faces challenges due to low oil prices, which have significantly increased the biofuel subsidy expenditure – based on the World Bank’s oil price projections, the Institute for Essential Services Reform (IESR) estimate that Indonesia’s palm oil fund will be depleted as soon as 2021, compared to their pre-COVID estimate of 2027 (IESR 2021e). Under these circumstances the government has postponed plans to increase the biodiesel blending mandate to 40% (IESR 2021e) and produce ‘green diesel’ entirely with palm oil (Diela, Munthe, and Nangoy 2020).

Presidential Regulation 44/2020 now mandates all oil palm plantations must be certified under the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) scheme. While this is a positive development, the efficacy of the ISPO scheme has been questioned, since certified plantations are still involved in deforestation and social conflicts (Forest Watch Indonesia 2017). The effective implementation of this policy at all levels of government remains a key challenge for managing the environmental and social risks of biofuel production in Indonesia.

Environmental regulations were eased under the radar as the government passed the Omnibus law in late 2020, which transfers the decision-making power from local to the central government for deliberation about environmentally sensitive projects. The regulation is considered a significant setback as it downgrades the importance of environmental licenses and reduces the efficiency of monitoring mechanisms (Sembiring, Fatimah, and Widyaningsih 2020).

Indonesia has also been back and forth with the requirements on certification for wood production, which raised concern about increases in illegal logging (Iswara 2020). In an attempt to boost wood exports, regulation 15/2020 discarded the SVLK verification system, which ensures the legality and sustainability of all wood exports. The regulation was supposed to take effect on May 27. However, regulation 45/2020, which took effect on May 11, reinstated the mandatory provision of the certificates for exports (Jong 2020; Myers 2020).

Energy supply

Recent developments in Indonesia highlight the conflict between increasing support for and deployment of renewables, and the continued expansion of fossil fuel capacity, mainly coal, locking in Indonesia’s long-term fossil fuel dependency. The government missed the opportunity to foster a green recovery, allocating just 3.5% of the total recovery budget to clean energy development (Energy Policy Tracker 2020; IESR 2021e).

The Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources’ strategic plan 2020-2024 (based on the government’s mid-term development plan (RJPMN) 2020-2024) and PLN’s electricity supply business plan (RUPTL) 2021-2030 are two of the core documents that underpin energy sector development in Indonesia. The targets set in the RJPMN are considered in our planned policies projections, while the new RUPTL is considered in our current policy projections.

Coal

Since 2010 Indonesia has commissioned around 23 GW of coal power capacity and by the end of 2020 had a further 11 GW under construction – amounts only exceeded by China and India (Global Energy Monitor et al. 2021). The coal power plant pipeline is part of the Government’s 2015-2019 35 GW Plan that was initiated to increase the electrification ratio while meeting the forecast growth in energy demand.

The new RUPTL fails to shift away from coal-fired power, which accounts for around 14 GW of the added capacity planned between 2021 and 2030. In comparison with the previous revision, the new RUPTL lowers planned generation from coal by almost 15 TWh in 2028 (latest year for comparison), however, due to a downward revision of total generation (100 TWh in 2028) and gas-powered generation, the share of coal increases from 54% to 63% in the new plan. The current plans for the electricity sector are not aligned with the goals of the Paris Agreement, for which Indonesia would need to reduce the share of coal-fired power generation to a maximum of 10% by 2030 (Climate Action Tracker 2020b).

Repeated overestimations in demand growth have burdened PLN with oversupply in several main grids like Java-Bali and Sumatra (IEEFA 2021). The increase of coal in power generation is not in line with the decarbonisation needed to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement (see Figure 1). While achieving the targets of the NEP and RPJMN 2020-2024 would result in emission reductions beyond current policy projections, the roles of especially coal, but also oil and gas, would remain significant in the coming decades, making a deep reduction of emissions extremely difficult and very costly.

The current plans for the electricity sector, in which 64% of the demand is met by coal-fired power plants in 2030, are not aligned with the goals of the Paris Agreement, for which Indonesia would need to reduce the share of coal-fired power generation to a maximum of 10% by 2030 and be phased out coal by 2040 (Climate Action Tracker 2020b).

The continued reliance on coal, not only in the power sector, but also in the development of the downstream industry, increases the risk of stranded assets and takes Indonesia even further from achieving a just transition (IESR 2021b; 2021e). The financial agreements for coal-fired power plants increase risk of locking-in costly capacity payments to thermal power plants while renewables become cheaper.

The agreements between PLN and independent power producers (IPPs) ensure a minimum payment for each kilowatt available – not necessarily dispatched. These values might reach up to 40% of the tariff value that the government needs to pay to IPPs during the duration of the whole contract and are estimated to lead to an obligation to pay over USD 16bn for coal idle capacity until 2026 (IEEFA 2017).

Renewables

Renewables have faced significant delays and accounted for just 11% of the added capacity between 2019 and 2020 (Republic of Indonesia 2021). Hydropower saw the largest increase (193 MW) reaching 5.2 GW, followed by solar (14 MW) reaching 79 MW, and geothermal (3 MW) reaching 2.4 GW. The installed capacity of biomass power plants fell by almost one third (52 MW) to 120 MW, while other renewables (mainly wind), remained at 131 MW. Installed capacities fell short of the targets set by the national energy plan (RUEN) – while hydropower and geothermal reached 80% of these targets, solar, bioenergy, and other renewables reached just 8%, 5%, and 4%, respectfully.

The potential for renewables is largest for solar power, estimated by the MEMR as 208 GW (although the IESR estimate that the technical potential for solar is almost three times greater than the MEMR estimate (IESR 2021a). Indonesia also has significant potential for hydropower (94 GW), wind power (61 GW), bioenergy (33 GW), geothermal (29 GW), and wave power (18 GW) (National Energy Council (DEN) 2019).

The Australian National University shows that with this large renewable energy potential Indonesia could generate 100% of its electricity from renewables and be energy self-sufficient (Silalahi et al. 2021). To date, the utilisation of renewable energy potential is low, ranging from just 0.03% for solar power to 5% for hydropower. The recent record-low bids for renewables like floating solar PV (3.68 USDc/kWh) shows these technologies are already competitive in the Indonesian context (IESR 2021e). To realise the full potential outline above, the Government must address the many barriers facing renewable energy development (IESR 2021d).

Recent policies to foster renewables development have not been so successful, but some steps have been taken to improve their effect. The second amendment of MEMR Regulation 50/2017 (MEMR 4/2020) renews the possibly for PLN to use direct appointment, removes the requirement for projects to operate under the ‘build, own, operate, and transfer’ (BOOT) scheme, and enforces PLN to prioritise IPP renewable power sales without a restriction on capacity. Although the amendment addressed several barriers to renewables, it failed to deliver the much-needed revision of the renewable tariff scheme, which remains limited to 85% of the local average generation cost (MEMR Indonesia 2017).

The Renewable Energy (EBT) bill, prepared by the House of Representatives Commission VII in January 2021, is still in the process of consolidation (IESR 2021f). There have been significant changes in the terms since its first draft and it remains to be seen what the scope of the final bill will be.

Regulation 49/2018 establishes a net metering scheme in which the users are compensated for only 65% of the electricity they put into the grid (MEMR Indonesia 2018). The regulation has been amended twice, improving the competitiveness of rooftop PV by easing the administrative process and reducing charges applicable for the industry sector (IESR 2019).

While these improvements are expected to improve the technology uptake, it does not address the cap in the compensation (IESR 2019). Both original and amended regulations result in prices that are still too low for investors to make a reasonable profit against highly subsidised coal and do not account for the broader social benefits of investing in renewables (Suharsono et al. 2019). While they support keeping consumer prices and overall subsidies at current levels, they do not bring Indonesia closer to meet its renewable targets.

The overarching targets for the energy sector are set by the National Energy Policy (NEP) – increase the share of renewables in both primary energy and electricity to 23% by 2025 and 31% by 2050. However, renewables uptake has not been consistent with this target – in 2019 the share of renewables in primary energy and electricity was 10% and 13%, respectively (ESDM 2020; Republic of Indonesia 2021). Under current policy projections, the NEP targets will not be met: the assumed role of coal in our projections is stronger than what it would be under the NEP (read more in Assumptions).

While renewables account for 52% of the planned capacity under the RUPTL 2021-2030, this does not reflect any change in Indonesia’s renewables target, which remains at 23% by 2030. In comparison with the previous revision, the forecast for total generation from renewables decreases by 22 TWh in line with the overall downwards revision of electricity demand in 2030. Hydropower and geothermal have been reduced by 17 TWh and 14 TWh respectively, while other renewables (mainly solar and wind) increase by almost 9 TWh by 2030 in the new RUPTL.

Biofuels

Biodiesel exports plummeted from 1.3 billion litres to just 0.04 billion litres (Statistica 2021), partly due to lower global energy demand, but also due to the EU’s recent policy to ensure the sustainability of imported biofuels, and increasing domestic biofuel production in China (IESR 2021e).

Domestic biodiesel consumption reached 8.5 billion litres in 2020, falling just short of the 9.6 billion litres target, in part due to lower demand during the pandemic (IESR 2021e).

Indonesia’s biofuel consumption mandate is one of the most ambitious in the world. Since 2016 and prior to 2020, biofuels had to supply 30% of the energy in the electricity sector, and 20% in micro-business, fisheries, agriculture, transportation, industry, and public service sectors. In the same regulation, the target share values for all sectors increased to 30% in 2020, with plans to increase the mandate to 40% between 2021 and 2022 (Reuters 2020; ESDM 2015; ICCT 2016).

Plans to increase the blending have been postponed until 2022 due to lack of funding for the subsidy caused by low oil prices during the pandemic. Based on the World Bank’s oil price projections, Indonesia’s palm oil fund will be depleted as soon as 2021, compared to its pre-COVID estimate of 2027 (IESR 2021e).

Biofuels in the development phase (bioethanol and ‘green diesel’) have faced delays. By early 2021 domestic bioethanol production had not started due to high production costs and lack of subsidy. Green diesel production from pure palm oil is planned to scale-up from 2022, following successful trials by Pertamina in 2021 (IESR 2021e).

Deforestation is a key issue surrounding biofuel development in Indonesia since commodity-driven deforestation (such as oil palm plantations) are the main driver for tree-cover loss (see Forestry section). Until 2020, biofuel suppliers were exempt from the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) certification scheme. Presidential Regulation 44/2020, passed in March 2020, now mandates all oil palm plantations to be certified under the ISPO scheme. While this is a positive development, the efficacy of the ISPO scheme has been questioned, since certified plantations are still involved in deforestation and social conflicts (Forest Watch Indonesia 2017). The effective implementation of this policy at all levels of government remains a key challenge for managing the environmental and social risks of biofuel production in Indonesia.

Industry

In 2019, industry accounted for 6% of Indonesia’s total emissions (excl. LULUCF). Cement, ammonia-based fertilisers and metal industries are the largest emitting industry subsectors in Indonesia (Republic of Indonesia 2018b).

The Indonesian government is focussed on reducing cement industry emissions by lowering clinker-to-cement ratio (Republic of Indonesia 2018a). Voluntary guidelines have been developed to encourage the use of blended cement by using clinker substitutes such as fly ash, and by using biomass and other alternative fuel and raw materials (AFR) in the cement production process. Indonesia also has various CDM projects in the industry sector, ranging from clinker replacement in the cement industry to oil field flaring reduction (UNFCCC 2018). In addition, there are plans for energy audits and conservation for all energy intensive industries (Republic of Indonesia 2018b). The CAT has not quantified the impact of those policies separately.

Transport

The expansion of zero emission fuels in the transport sector is essential for meeting the 1.5°C temperature limit. While Indonesia has strategies in place to support both the use of biofuels and electric vehicles, outcomes are not currently aligned with Paris compatible benchmarks (Figure 2).

Biofuels

Indonesia’s biofuel policy mandates high shares of biofuel consumption in the transport sector. Since 2016 and prior to 2020, biofuels had to account for at least 20% of diesel consumption in the sector and by 2020 this share increased to 30% (see Energy section).

Although current biofuel production is dominated by biodiesel, the government also has plans to produce bioethanol, targeting 20% blending by 2025 in the National Energy Policy. However, by 2020 bioethanol production had not started due to high production costs and low subsidies (IESR 2021e).

While Indonesia’s biofuels targets are ambitious, they are not without controversy due to concerns with palm oil production (see Energy section).

Electric vehicles

In the face of increasing concerns about air pollution, Indonesia is shifting its attention towards electric vehicles (EVs). An Electric Vehicles Development Plan and Targets are part of the General Plan of National Energy published in 2017 (Republic of Indonesia 2017). This plan presents the vision of over 2,000 four-wheeled EVs, 700,000 hybrids, and over two million electric two-wheelers on the streets by 2025; these numbers increase to four, eight, and 13 million by 2050. An EV share of the total stock of light vehicles of about a third of the total fleet (including two and three-wheelers) by 2030 would be a benchmark consistent with the Paris Agreement, reaching between 80% to 90% by 2050 (CAT, 2020).

By September 2020, Indonesia recorded around 2,300 EVs (80% two-wheelers) – well short of the RUEN targets of 900,000 EVs by 2020 and 2.3 million EVs by 2025 (IESR 2021e). The RUEN 2020 targets were also missed for EV production (0.15% and 0.26% progress for electric cars and two-wheelers, respectively) and EV infrastructure (43% progress).

In 2019, the government issued a regulation to boost the domestic electric vehicle (EV) industry and to support reaching these targets. Regulation 55/2019 is the first attempt to grow a new market by providing incentives to manufacturers and consumers, although the specifics are still not well defined. The regulation provides targets for the local content share (minimum level of goods and services required to be bought and/or manufactured locally) required to reach 80%, by 2026 for two or three wheeled-vehicles and by 2030 for four wheelers; it also indicates that charging stations can be privately owned (President of the Republic of Indonesia 2019). Nonetheless, the regulation neither provides a clear roadmap for the rollout of the strategy nor presents details on the incentives supporting the uptake of EVs (IESR 2019).

Several regulations were introduced in 2020 to support Regulation 55/2019, providing fiscal incentives to lower the cost of EV ownership and infrastructure development, however, these are still insufficient to make EV purchase prices comparable with conventional vehicles in Indonesia (IESR 2021e).

In 2020, Indonesia had installed 62 charging units, just 27 of which are open for public use, falling very short of PLN’s target for 180 units outlined in their public charging station roadmap (2020-2024) (IESR 2021e). The target for charging stations is also not aligned with the number of EVs targeted in the RUEN – the ratio of charging stations to EVs in 2025 will be seven times lower the 1:10 ratio recommended by the IEA (International Energy Agency 2018; IESR 2021e).

Transport infrastructure & public transit

Mitigation actions on transport infrastructure and planning in Indonesia are being guided by the Transportation Decree No. 201/2013 (Climate Policy Database 2013). They include a major overhaul of the existing system with an "avoid, shift and improve" approach, including the construction of Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) corridors, implementation of traffic management technologies to reduce congestion, and construction of urban railway systems (Republic of Indonesia 2018a). The Sustainable Urban Transport Program (SUTRI) Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Action (NAMA) is being implemented in seven pilot cities and will be a key instrument to support transformation in the transport sector. The NAMA aims to improve public transport and implement transport demand management measures, e.g. road pricing and public bicycle schemes (Ministry of Transportation 2014).

Jakarta, the Indonesian capital, has approximately one million commuters every day. The city’s Transport Master Plan states that public transport should reach 60% of the passenger ridership by 2029 (Republic of Indonesia 2018c). In March 2019 the first line of Jakarta’s Mass Rapid Transit system opened. A second line is expected to be completed by 2024. A key challenge now is securing the modal shift in commuter habits. The transit system is currently only used by 20% of commuters.

Buildings

The growing middle-class energy demand means a continued relevance of the building sector in Indonesia. Emissions per capita in the sector have more than tripled since 1990 (see chart below). To mitigate the impacts of growing demand, the Indonesian government has set targets to reduce total final energy consumption in the buildings sector (both commercial and housing) by 15% compared to a BAU by 2025 (ASEAN Centre for Energy and GIZ 2018).

Regulation 36/2005 under Law No. 28/2002 sets energy standards for buildings (SNI) concerning building envelop, air conditioning, lighting appliances, and energy audit procedure (GBPN 2013). Also, Energy Performance Certificates are mandated for building users whose energy consumption is beyond 6,000 toe/a. These users are required to conduct an energy audit and implement its recommendation, and report result of the implementation energy measures to the government.

Indonesia also has a mandatory labelling for lighting ballasts (since 2011), energy standards, and mandatory labelling for air conditioning (since 2016) that are also under development for refrigeration, cooking, washing machines, dishwashers and motors (CLASP 2018; IEA 2016). In addition, municipal actors have been active in promoting green building concepts.

In 2012, Jakarta passed a mandatory Green Building regulation. Compliance with energy conservation and efficiency regulations for large buildings that is reinforced through the issuance of building permits and the shutdown of buildings that do not comply with the established criteria (ASEAN Centre for Energy and GIZ 2018).

Agriculture

The overall emissions intensity of the agriculture sector has been on a declining trend in Indonesia for the past 20 years. Nonetheless, the demand for biofuels has impacts on the agricultural and land use sector, as this demand may be met by expanding domestic palm oil industries. We have only quantified the impact the biofuels mandate would have in the transport under our current policy projection, but have included lifecycle emissions when assessing emissions reduction impact (see Assumptions).

Until 2020, biofuel suppliers were exempt from the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) certification scheme. Presidential Regulation 44/2020, passed in March 2020, now mandates all oil palm plantations to be certified under the ISPO scheme. While this is a positive development, the efficacy of the ISPO scheme has been questioned, since certified plantations are still involved in deforestation and social conflicts (Forest Watch Indonesia 2017). The effective implementation of this policy at all levels of government remains a key challenge for managing the environmental and social risks of biofuel production in Indonesia.

Since 2011, the government has had a palm-oil moratorium on new palm oil plantations in an area of 66 Mha. This moratorium has since been renewed, but the president has now issued a presidential instruction making it permanent (Diela 2019). The efficacy of the moratorium is ambiguous: while the policy is considered to be a good instrument to limit future deforestation in Indonesia (Mosnier et al. 2017) some research shows that deforestation has increased since it was implemented (Greenpeace Southeast Asia 2019). The policy can only be successful if properly enforced.

As of January 2019, suppliers involved in deforestation are suspended from sourcing to Wilmar International, one of the world’s largest agribusiness groups (Wilmar International 2018). Months later in June, the European Union, the second largest importer of Indonesian palm oil, introduced the Renewable Energy Directive (REDII), which imposes restrictions to ensure that the production of biofuel feedstocks is sustainable and does not drive deforestation through indirect land use change. These developments put pressure on the Indonesian Government and industry to create more sustainable supply chains in the country.

In 2018, Indonesia implemented a policy that mandates all state crops to maintain sustainable practices including banning the use of fire for land clearing (Republic of Indonesia 2018a). The government allocates its highest agriculture mitigation target to developing palm plantation areas on non-forested land/abandoned land/ degraded land/other use areas, but the exact approach to achieving this is neither well-explained nor easily traceable (Republic of Indonesia 2018b).

Forestry

Indonesia’s emissions from Land-use, land-use change and forestry have accounted for almost 50% of the country’s total emissions over the last 20 years. Emissions from the sector have shown strong fluctuations at a high level, and with an increasing trend. Reducing emission from deforestation is a vital part of Indonesia’s climate action.

Indonesia alone contributed to 7% of the total global tree cover loss between 2001 and 2020 (Global Forest Watch 2021). The country contributes to a large share of LULUCF emissions reaching around 1 GtCO2e/a, considering deforestation, forest degradation, peat decomposition, and peat fires (Alisjahbana and Busch 2017; UNFCCC 2015). Due to an unusually high occurrence of peat fires, the emissions from the LULUCF sector in Indonesia reached almost 1.4 GtCO2 in 2015. To put that in context: global emissions from LULUCF were about 4.1 GtCO2e in 2016 (FAOSTAT 2018).

Assessing a LULUCF emissions trajectory is somewhat complicated by the fact that these emissions have shown large fluctuations due, among other things, to the variability of emissions from peat fires to external factors such as the influence by El Niño. Emissions projections for the LULUCF sector show that current policies remain insufficient to curb down emissions (Figure 4) (Nascimento et al. 2021).

The LTS envisages this sector becoming a net sink by 2050 under the current policy scenario, and by 2030 under the ambitious low carbon scenario compatible with the Paris Agreement (LCCP). However, emissions projections from this sector under current policies range from a 42 MtCO2e/a decrease, to a 76 MtCO2e/a increase between 2020 and 2030, remaining a net source of emissions by 2030 (Nascimento et al. 2021). To achieve its NDC targets, Indonesia must achieve a decrease in LULUCF emissions. If this sector is taken into account, more ambitious actions would be needed to reach the NDC targets considering both the reinforcement and expansion of the current forestry moratorium (Wijaya et al. 2017).

Although Indonesia has made significant progress in reducing deforestation and forest fires, these problems persist. Weak implementation of commitments to international agreements, contradictory regulations and objectives, and poor coordination between government agencies and ministries are key challenges to achieving greater reductions in this sector (Dwisatrio et al. 2021). The outlook of this sector worsened in 2020 with the passing of the Omnibus law, which significantly weakens Indonesia’s environmental protection regulations. The regulation removes the “strict liability” clause, which will make it more difficult to prove and prosecute businesses that clear land using forest fires, removes limitations on minimum forest cover for river basins and islands, and centralises decision making processes regrading permitting forest areas (Investment Policy Hub 2020).

Fires are a major source of LULUCF emissions in Indonesia and are used as a cheap and easy way to clear land for commodity plantations like palm oil. In 2019, the Indonesian fires were again a special reason for concern: in just the one week of 9 September there were almost 64,000 fire alerts in the country (Global Forest Watch 2021), causing a state of emergency in at least six Indonesian provinces and sparking complaints from neighbouring countries that were affected by the toxic haze (Walden 2019). The peak number of alerts in a single week decreased to 6,000 in 2020 and to below 4,000 in 2021 (Global Forest Watch 2021).

Indonesia has seen a decreasing trend in tree cover loss since 2016 and by 2020 this amounted to 962 kha, the lowest level since 2003 (Global Forest Watch 2021). While this reduction is a good sign, the biggest driver for deforestation is still commodity-driven deforestation, which accounted for over 90% in 2019. The underlying cause of commodity-driven deforestation is economic development. The expansion of commodity industries like palm oil is driven by global demand and fostered by national development policies (Dwisatrio et al. 2021).

To reduce LULUCF emissions, Indonesia has signed several international agreements on forest governance and the protection of biodiversity (UNFF, FLEGT, Amsterdam Declarations, Bonn Challenge and the New York Declaration on Forests, CBD, CITES) and made changes to the institutional arrangements and regulations relating to the reduction of emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (Dwisatrio et al. 2021).

As part of the National Action Plan for Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction (RAN-GRK), Indonesia identified actions in the forestry sector. Those are sustainable peat land management, reducing the deforestation and land degradation rate, and developing carbon sequestration projects in forestry and agriculture (Mersmann et al. 2017). These efforts are reinforced through the REDD+ Task Force, which in the short- and medium-term focuses on improving governance of forests, and in the long term aims at turning Indonesia’s forests and lands into a net carbon sink. In the Third National Communication, Indonesia describes 13 “core mitigation plans” that have been pursued since 2010, each with a quantitative emission reduction target attributed to them, adding up to reductions of 810 MtCO2e/a.

Laws in place to regulate the sector are the moratorium for new permits and improvement of forest and peatland governance and the National Strategy for Forest Law Enforcement in Indonesia from 2005, a programme to combat illegal logging. The policy constitutes not just a freeze on new licenses, but an order for the relevant central government ministries and regional governments to conduct a massive review of palm oil licensing data. Indonesia is also in the process of implementing the One Map Policy, with the objective to create a transparent monitoring system of forest areas (Mulyani and Jepson 2016).

We made separate analyses of Indonesia’s LULUCF emissions in our 2015 and 2016 assessments. LULUCF emissions are a huge uncertainty factor in assessing the extent to which Indonesia is in line with meeting its NDC. The CAT does not assess the LULUCF component of the NDC; however, both conditional and unconditional targets depend heavily on the forestry sector. It comprises about 60% of the emissions reduction effort.

Further analysis

Country-related publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter