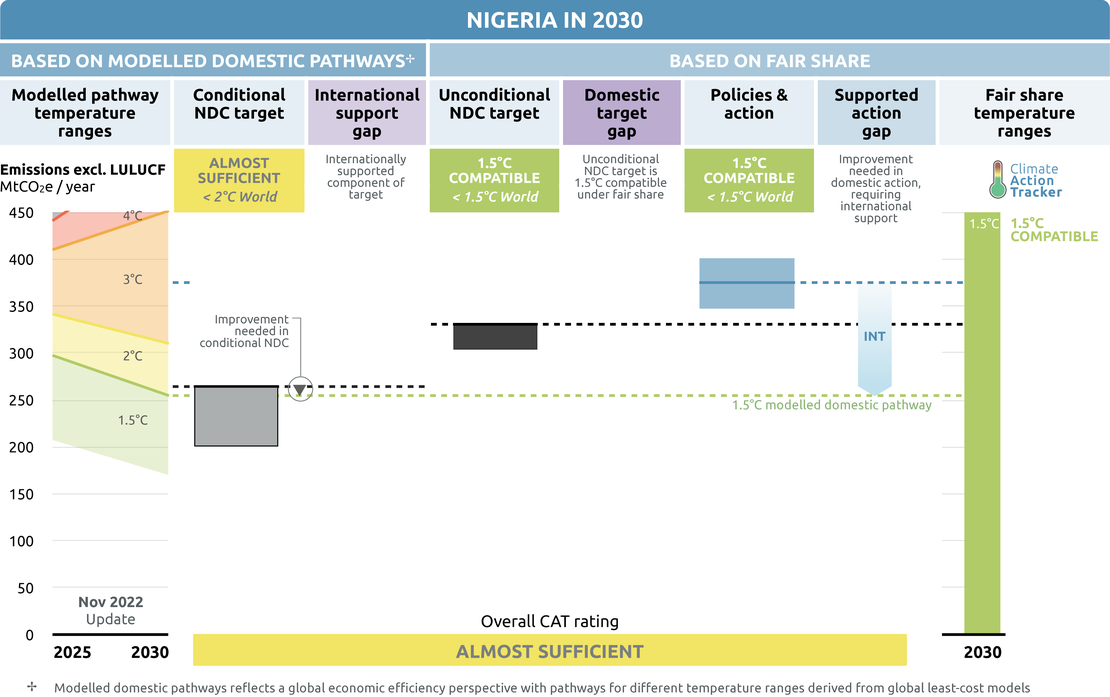

Policies & action

CAT estimates that Nigeria’s greenhouse gas emissions would reach 34-54% above 2010 levels excluding LULUCF in 2030 under current policies and including the impact of COVID-19.

Nigeria’s current policies are rated "1.5˚C compatible" when compared to its fair share contribution. The “1.5˚C compatible” rating indicates that Nigeria’s climate policies and action are consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C. Nigeria’s climate policies and action do not require other countries to make comparably deeper reductions.

While Nigeria’s policies and action are consistent with a fair contribution to climate action, they do not put Nigeria on track to meet either of its targets. These policies are also inconsistent with the level of emissions cuts needed to limit warming to 1.5°C. Implementation of the ETP, reflected in our planned policies scenario, would put Nigeria on track to meets its unconditional target, but not its conditional target.

Nigeria will need to implement additional policies with its own resources to meet its unconditional target, but will also need international support to implement policies in line with full decarbonisation to meet and exceed its conditional target.

Key steps to reducing the gap between current policies and Nigeria’s NDC targets include progressing towards and ramping up its renewable energy target and halting the expansion of natural gas.

Policy overview

In June 2021, the government approved a revised National Climate Change Policy (NCCP) and National Climate Change Programmes for Nigeria for the period 2021-2030 (Department of Climate Change, 2021).

The NCCP outlines mitigation and adaptation policy measures, enabling conditions and means of implementation necessary to achieve Nigeria’s climate objectives. While the NCCP is meant to align with the updated NDC, it presents historical emissions more than double the historical emissions for the same year in the NDC. The NCCP further identifies AFOLU as the largest emissions source (66.6%), while the updated NDC indicates AFOLU is about a quarter of emissions.

In 2019, Nigeria adopted a National Action Plan on Short-lived Climate Pollutants, with 22 measures to reduce emissions, including reducing methane from fugitive emissions and leakages from oil production and processing and natural gas transportation and distribution (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2019).

Nigeria adopted the Economic Sustainability Plan (ESP) to stimulate the economy in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Economic Sustainability Committee, 2020). The ESP includes climate-related programmes, including the installation of five million solar homes and a national gas expansion programme to reduce reliance on oil. In the Middle East and Africa, unabated natural gas in power generation needs to effectively phase out by 2045 (Fyson et al., 2022).

In November 2021, Nigeria passed the Climate Change Act that seeks to achieve low greenhouse gas emission, green and sustainable growth by providing the framework to set a target to reach net zero between 2050 and 2070 (Okereke & Onuigbo, 2021). For more analysis on the Climate Change Act, please see our net zero target analysis here.

In addition to the net zero provision in the Climate Change Act, President Buhari also announced the government’s commitment to achieve net zero emissions by 2060 (Lo, 2021). In August 2022, Nigeria released its Energy Transition Plan (ETP) to serve as the pathway towards achieving this target (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2022). The plan targets significant long-term action through sectoral targets; however, it relies heavily on action after 2030, declared the “Decade of Gas” by the government.

Nigeria is developing a 2050 Long-Term Vision on climate change with support from the 2050 Pathways Platform and a long-term development plan, Agenda 2050 (Akinola, 2020; The Premium Times, 2020).

Sectoral pledges

In Glasgow, a number of sectoral initiatives were launched to accelerate climate action. At most, these initiatives may close the 2030 emissions gap by around 9% - or 2.2 GtCO2e, though assessing what is new and what is already covered by existing NDC targets is challenging.

For methane, signatories agreed to cut emissions in all sectors by 30% globally over the next decade. The coal exit initiative seeks to transition away from unabated coal power by the 2030s or 2040s and to cease building new coal plants. Signatories of the 100% EVs declaration agreed that 100% of new car and van sales in 2040 should be electric vehicles, 2035 for leading markets. On forests, leaders agreed “to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030”. The Beyond Oil & Gas Alliance (BOGA) seeks to facilitate a managed phase out of oil and gas production.

NDCs should be updated to include these sectoral initiatives, if they aren’t already covered by existing NDC targets. As with all targets, implementation of the necessary policies and measures is critical to ensuring that these sectoral objectives are actually achieved.

| Signed? | Included in NDC? | Taking action to achieve? | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methane | Yes | No | Yes |

| Coal Exit | No | N/A | N/A |

| Electric vehicles | No | N/A | N/A |

| Forestry | Yes | No | Yes |

| Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance | No | N/A | N/A |

- Methane pledge: Nigeria signed the methane pledge at COP26. This is significant, given its high methane emissions in its oil and gas operations. Methane accounted for 51% of emissions excluding LULUCF in 2021(Gütschow & Pflüger, 2022). A direct reference to the pledge is not included; however, the 2021 updated NDC includes targets to reduce oil and gas fugitive methane emissions by 60% by 2031 and methane from organic solid waste by 10% (neither target specifies a base year) (Federal Government of Nigeria, 2021).

Since Glasgow, Nigeria has published its Energy Transition Plan which includes the target to eliminate gas flaring by 2030 and reduce fugitive emissions 95% by 2050(Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2022). A 30% reduction in methane below 2020 levels is equivalent to an almost 50 MtCO2e/yr reduction. The NDC update estimates that full implementation of the measures in the update would reduce methane emissions 28% by 2030 compared to a (non-specified) baseline scenario (Federal Government of Nigeria, 2021). - Forestry: Nigeria signed the Leaders' declaration on forest and land use at COP26. Nigeria’s updated NDC includes several measures targeting the forest sector, including forest restoration and protection and reduced fuelwood harvest (Federal Government of Nigeria, 2021). More details on Nigeria’s policies and actions related to the forestry sector can be found below.

Energy supply

The energy sector is the largest source of emissions in Nigeria, responsible for more than 60% of the national total (Federal Ministry of Environment, 2021b). Fugitive emissions from oil and gas are the largest source of energy emissions, followed by transport, electricity generation, residential and industrial consumption.

In August 2022, Nigeria released its Energy Transition Plan (ETP) to serve as the pathway towards achieving the 2060 net zero target (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2022). The plan targets significant long-term action through sectoral targets, but it relies heavily on action after 2030, declared the “Decade of Gas” by the government. The ETP plans to use gas as a “transitionary fuel” with large increases in gas consumption in the power, cooking and industry sectors by 2030 before a near total phase-out by 2050 (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2022). This risks Nigeria investing in stranded assets and locking-in carbon-intensive infrastructure.

The government is in the process of finalising Nigeria’s Medium-Term National Development Plan (MTNDP) for 2021-2025. The current draft MTNDP includes strategies to expand gas and transmission and distribution infrastructure, promote renewables and increase commercialisation of upstream gas to reduce flaring (Ministry of Finance Budget and National Planning, 2021).

Oil & Gas

Nigeria, a member of OPEC, is the 11th largest oil producer in the world. Nigeria is also the 17th largest natural gas producer in the world and plans to increase current production threefold (IEA, 2021a; The Guardian, 2021). Nigeria’s economy is highly dependent on its oil and gas sector, accounting for about 56% of government revenue in 2019 (Central Bank of Nigeria, 2020).

Amid the global energy crisis, European interest in importing natural gas from Africa has surged (Aljazeera, 2022). This has spurred renewed interest in export infrastructure projects, primarily the Nigeria-Morocco Pipeline, even though new export infrastructure would not be operational in time to counter the short-term impacts of the crisis (Rahhou, 2022).

Despite increased demand and its intentions to ramp up production, Nigeria has struggled to meet current supply obligations, largely due to rampant crude oil theft impacting Nigeria LNG’s operations with production at 60 to 68% utilisation in June (Reuters, 2022). Further, the deadly flooding starting in October 2022 and expected to continue into November has impacted production. After all of Nigeria LNG’s upstream suppliers declared force majeure, the company did the same (Nigeria LNG Limited, 2022a, 2022b).

This rise in the use of natural gas in Africa and globally is not aligned with the Paris Agreement goal to limit global warming to 1.5°C. Relying on natural gas runs the risk of investing in stranded assets as future gas demand is subject to large uncertainties. CAT analysis shows that shifting to renewables would not only put Nigeria on a 1.5°C compatible pathway, but would also create more jobs than its current gas-based strategy.

Nigeria’s COVID-19 stimulus plan, the Economic Sustainability Plan (ESP), includes a domestic gas utilisation programme aimed at reducing the country’s reliance on oil (Economic Sustainability Committee, 2020). This includes the promotion of compressed natural gas (CNG) for use in the transport sector.

Nigeria adopted its Gas Master Plan in 2008 with the goal of expanding its domestic, regional and export gas markets (Ukpohor, 2013). The plan has three main elements: a gas pricing policy to ensure affordable prices, a domestic gas supply obligation requiring all gas producers to set aside a predetermined amount for domestic use, and a gas infrastructure blueprint for production, processing and transmission infrastructure. Nigeria’s gas production has increased 37% from 2008 to 2019 (IEA, 2020b). However, to keep warming to 1.5˚C, gas must be phased out, not increased.

Globally, unabated natural gas in power generation needs to peak before 2030 and be halved by 2040 below 2010 levels. Further, according to the IEA, no new oilfield development is needed if we are serious about the world reaching net zero emissions in 2050 (IEA, 2021b).

In August 2021, President Buhari signed the Petroleum Industry Bill (PIB) into law to improve transparency and accountability in the oil sector and ultimately attract more international investment in the sector (Esiedesa, 2021; Thomas, 2020). This comes after 20 years of attempts to pass the bill (Ene, 2018; Iroanusi, 2021). However, increased expansion of oil infrastructure and production increases the risk of costly stranded assets as countries and private sector actors divest from fossil fuels.

Environmental groups have criticised the PIB for including exemptions that allow gas flaring to continue. Further, under the PIB, unlike with upstream fines, midstream gas flaring fines will be used for more gas investment rather than, for example, hosting community development or environmental remediation (EnviroNews Nigeria, 2021; KPMG in Nigeria, 2021).

Gas flaring

In 2000, Nigeria was flaring roughly 55% of the gas it was extracting. To reduce emissions from gas flaring, Nigeria set the goal of completely eliminating routine flaring by 2020, a decade ahead of the World Bank’s “Zero Routine Flaring by 2030” initiative. In 2018, Nigeria further adopted a gas flare commercialisation programme based on the “polluter pays” principle (Ogunleye, Banks, and Legarreta 2019). While Nigeria did not meet its 2020 target, it has made significant progress, now flaring 10% of extracted gas. The ETP targets zero flaring by 2030, as well as a 95% reduction of fugitive emissions from oil and gas by 2050 (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2022).

Electricity

In the power sector, natural gas supplied about 83% of electricity generation in Nigeria in 2018 (IEA, 2020a). The remaining generation is supplied by hydropower and negligible shares of solar PV.

Nigeria’s electricity supply is one of the least reliable in Africa. It has the most frequent and prolonged power outages on the continent (IEA, 2019). In Nigeria’s Sustainable Energy for All (SE4ALL) Action Agenda, Nigeria aims to supply 90% of the population with access to electricity and 80% using modern cooking fuel by 2030 (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2016). These reliability issues contribute to Nigeria’s high reliance on expensive oil-fired back-up generators (IEA, 2019).

Nigerians spend about USD 14bn per year on generators and fuel, producing an estimated 29 MtCO2e annually (Moss & Gleave, 2014; Olalekan, 2020). In 2019, Nigeria and Germany formed a partnership to upgrade Nigeria’s transmission and distribution infrastructure to secure 11,000 MW of reliable power supply by 2023 (The Premium Times, 2019).

The Energy Transition Plan (ETP) identifies the elimination of diesel and petrol generators as the key strategy for the power sector. In the long-term, the ETP aims to achieve this through an expansion of generation capacity, primarily from solar PV, by 2050. In the short-term, however, the ETP expects a ramp up in available gas capacity from 4 GW in 2020 to 14 GW by 2030. While the plan labels gas as a “transitionary fuel”, it still anticipates 10 GW of gas capacity in the energy mix by mid-century.

Renewables

In 2015, Nigeria adopted its National Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Policy (NREEEP) (Ministry of Power, 2015). This policy set an ambitious target of over 23 GW of renewable capacity including large hydropower by 2030; however, Nigeria is not on track to meet this goal.

Nigeria’s renewable capacity, including large hydropower in 2019, was just over 2 GW, substantially less than the NREEEP’s interim 2020 target of over 8 GW (IRENA, 2020). Nigeria’s SE4ALL Action Agenda adopted a year later includes more conservative targets, though Nigeria is not on track to meet those either (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2016). Based on IRENA estimates, Nigeria has only installed 17 MW of renewable capacity as of 2021, mostly solar PV, since either plan was adopted (IRENA, 2022). The ESP, Nigeria’s short-term economic plan following COVID-19, includes measures to install solar power in five million homes (Economic Sustainability Committee, 2020).

The ETP sets ambitious targets for renewables in the power sector, particularly solar PV (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2022). By 2050, the plan targets nearly 200 GW of solar PV, 11 GW of hydro, and 6 GW of biomass. The ETP estimates the power sector will require the highest level of investment, amounting to USD 270 billion in incremental investment from 2021 to 2060; however, it also expects fuel cost savings to offset USD 121 bn of this cost.

Transport

Nigeria’s COVID-19 stimulus plan, the Economic Sustainability Plan (ESP), includes a domestic gas utilisation programme aimed at reducing the country’s reliance on oil (Economic Sustainability Committee, 2020). This includes the promotion of compressed natural gas (CNG) for use in the transport sector.

Nigeria’s National Action Plan to Reduce Short-lived Pollutants includes measures to limit emissions from the transport sector (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2019). It aims to eliminate the use of high-emitting vehicles with a ban on vehicle imports more than 15 years old and increasingly stringent emission standards (Euro III by 2023, Euro IV by 2030). The plan also aims to renew the urban bus fleet in Lagos and adopt CNG buses across Nigeria, introduce low sulphur diesel and petrol, and promote a shift from road to rail and water transport.

In response to COVID-19, Nigeria also announced the removal subsidies for premium motor spirit fuels (Official Gazette, 2020). While pump prices in Lagos have risen from 145 to over 160 naira per litre, the government set price is still well below market value. The state-owned NNPC, the only gasoline importer in the country, has avoided the term “subsidy”, but has acknowledged the price difference which amounts to as much as NGN 120 billion (USD 294 million) in subsidies.

Nigeria had similarly announced the removal of subsidies in 2016 after a fall in oil prices, but returned to subsidising petrol in 2017 when crude prices rebounded. Uncertainty and confusion over government pricing has induced fuel shortages, likely due to a price hike by depot owners in anticipation of higher prices as international oil prices rebound (Olawoyin, 2021).

The Energy Transition Plan (ETP) sets the target to achieve 100% EVs by 2060, but progress towards this goal is largely seen after 2030 (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2022).

There is significant uncertainty around land use and forestry emissions estimates in Nigeria. The country’s Third National Communication (TNC) estimates LULUCF contributes to roughly half of Nigeria’s emissions (over 300 MtCO2e in 2016), while the NDC update reports land use emissions together with agriculture as about one quarter of emissions (approximately 87 MtCO2e in 2018) (Federal Ministry of Environment, 2020, 2021b).

Traditional biomass is Nigeria’s largest source of primary energy. In 2016, almost three quarters of households used fuelwood for cooking (Federal Ministry of Environment, 2020). Nigeria’s National Gas Expansion Programme, part of the Economic Sustainability Plan in response to COVID-19, aims to convert over 30 million homes from traditional fuels such as wood and kerosene to liquified petroleum gas to reduce emissions (Economic Sustainability Committee, 2020). Nigeria’s TNC estimated CO2 emissions from biomass consumption for energy production were about 70% of agriculture, forestry and other land use emissions (42% of total emissions) (Federal Ministry of Environment, 2020). The use of traditional biomass for cooking is linked to indoor air pollution and associated health risks as well as gender labour inequities (Addo & Olajide, 2021; Uchenna & Oluwabunmi, 2020).

In 2020, a new National Forest Policy was approved by the Federal Executive Council that is expected to boost climate efforts in the country, but the policy is not available online. It was reported that at the time of adoption by the National Council on Environment, the policy included a target to increase forest cover from the current 6% to 25% by 2030 (FME, 2019).

From 2001 to 2016, Nigeria’s tree cover decreased by 9.4%, largely due to shifting agricultural lands (Global Forest Watch, 2021). In July 2021, Nigeria launched its National Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD+) Strategy with the aim of reducing forest sector emissions by 20% by 2050 (Federal Ministry of Environment, 2021a; Olugbode, 2021). Pilot REDD+ activities have already progressed in Cross River State, home to half of Nigeria’s forests (FME & UNDP, 2019). Cross River State has developed its own REDD+ strategy and approach to safeguards and submitted its forest reference emission level to the UNFCCC.

Nigeria is a member state of the Great Green Wall (GWW) initiative. The initiative, launched in 2007 by the African Union, aims to restore degraded land, sequester carbon and create green jobs across in the Sahel region. Nigeria’s GWW programme has so far established a 1,359 km contiguous shelterbelt from Kebbi State in the northwest to Borno State in the northeast (UNCCD, n.d.). Other results so far include 2,801 hectares of reforested land and 1,396 jobs created.

Further analysis

Country-related publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter