Policies & action

The CAT rates Norway’s policies and action as “Almost sufficient”.

The “Almost sufficient” rating indicates that Norway’s climate policies and action in 2030 are not yet consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C but could be, with moderate improvements. If all countries were to follow Norway’s approach, warming could be held at—but not well below—2°C.

Current policies are projected to lead to emission levels of 37 MtCO2e by 2030 (excl. LULUCF), which is 27% below emissions in 1990. Norway will need to adopt further policies to meet its updated NDC target of reducing emissions by at least 55% below 1990 levels.

Policy overview

Since 1990, absolute emissions in Norway have decreased only slightly, reaching nearly 47 MtCO2e in 2023 (excl. LULUCF) (Government of Norway, 2025a). Under current policy projections, Norway will fall significantly short of its 2030 and 2035 targets: total emissions are projected to reach 37 MtCO2e by 2030 or around 27% below 1990 levels, highlighting the need for further policies and actions to reduce emissions. The gap between our current policy projections and Norway’s 2030 target has decreased compared to our last update.

A key plank of Norway’s Climate Action Plan 2021-2030 is the gradual raising of its carbon tax to USD 220 per tonne of CO2 by 2030 (Government of Norway, 2021b). The government argues that this will be sufficient to meet Norway’s commitment to the EU of reducing non-ETS emissions by 40% below 2005 levels by 2030. However, it is not clear how the carbon tax will meet Norway’s climate targets, as there is no precise quantification of its impact. Additionally, there is no review mechanism outlined that would calculate the full impact of Norway’s carbon tax on total emissions or consider prospective increases, something that is critical to ensure the price is at the level necessary to achieve the stated emission reduction targets.

A share of Norway’s reduction requirements could rely on international climate action and purchase of emissions quotas under the European regulatory framework. Such investments and purchases abroad are grounded on the cost-efficiency argument, considering that reductions in other countries are, overall, cheaper than more aggressive national policies. However, the CAT warns in our recent brief on Article 6 of the Paris Agreement that mechanisms like carbon credits and offsets should only be used to supplement true domestic action. Otherwise, Article 6 can be used to delay or avoid taking urgent action required to address the climate crisis.

While the power sector is largely decarbonised and the transport sector has made significant progress on electrification, Norway’s oil and gas sector continues to be a significant source of emissions, making up 17% of total emissions in 2024 (Norsk Petroleum, 2024). Given its significant fossil fuel exports, Norway is a large source of emissions in countries consuming its fossil fuel products (Scope 3 emissions). As a result of Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine, the EU has pivoted to buy more fossil gas from Norway. In 2024, Norwegian exports of fossil gas hit record numbers in six of the year’s 12 months (Gassco, 2025a).

The government has refused to adopt a phase-out target for oil and gas production and consumption, committing instead to an expansion of drilling and exploration in the Barents Sea. This decision was challenged before the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), which ultimately rejected the case in October 2025, but affirmed that Norway must assess the global impact of emissions when awarding new licenses for oil and gas drilling (Adomaitis, 2025). Regardless of the ECtHR’s ruling, such an expansion could be considered an “internationally wrongful act” under the International Court of Justice’s (ICJ) July 2025 advisory opinion on state responsibility in the climate crisis (Schwartzkopff, 2022).

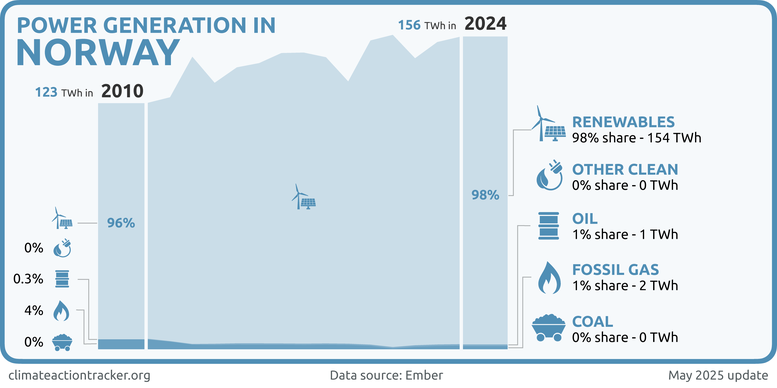

Power sector

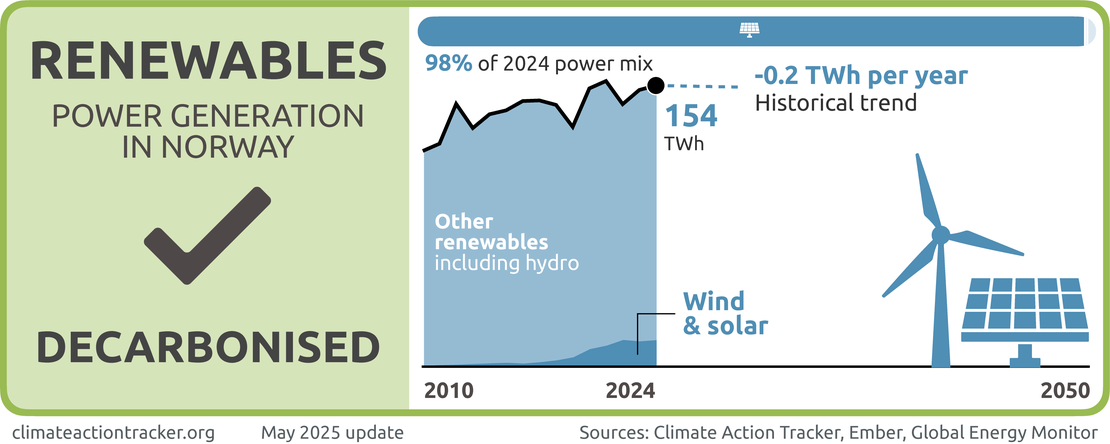

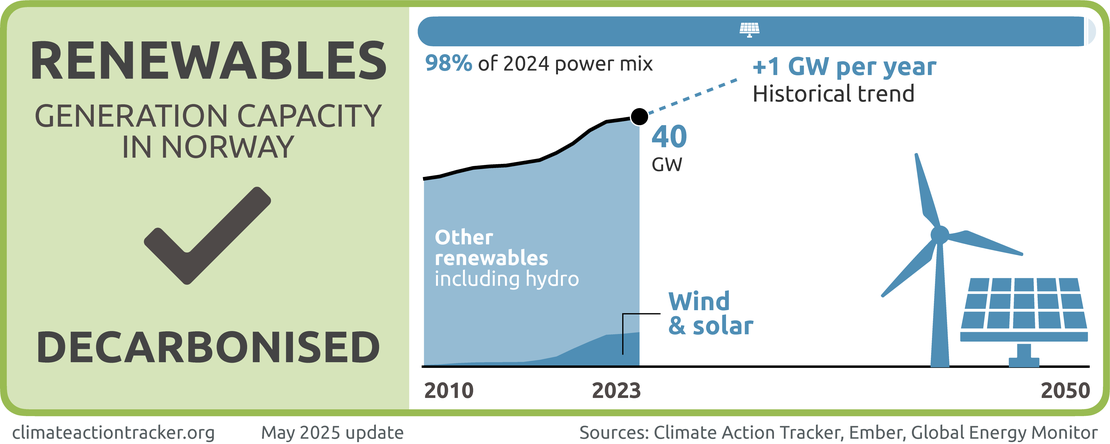

Electricity generation in Norway is almost exclusively renewable. In 2024, roughly 90% of electricity was generated by hydroelectric power plants - Norway has over 1000 storage reservoirs that correspond to 70% of annual Norwegian electricity consumption (Global Energy Monitor, 2024; Norwegian Ministry of Petroleum and Energy., 2022). The share of wind and solar in power generation has increased over the last five years, contributing around 10% of total generation in 2024.

Norway still has a small amount of fossil gas in its power sector, which has been increasing in both absolute amount and share of total generation. Despite this, the emissions intensity of Norwegian electricity is very low – around 19 gCO2/kWh in 2019, in comparison to over 300 gCO2/kWh for the EU (European Environment Agency, 2021). Coal does not play a role in Norway’s electricity supply, which is therefore evaluated as “Coal free”.

Depending on the weather each year, Norway can be either a net importer or exporter of power. When exporting a considerable supply of power, this contributes to lower the overall carbon intensity of neighbouring countries’ electricity consumption. This zero-carbon power is also often used on an hourly or daily basis to help balance the grids of neighbouring countries.

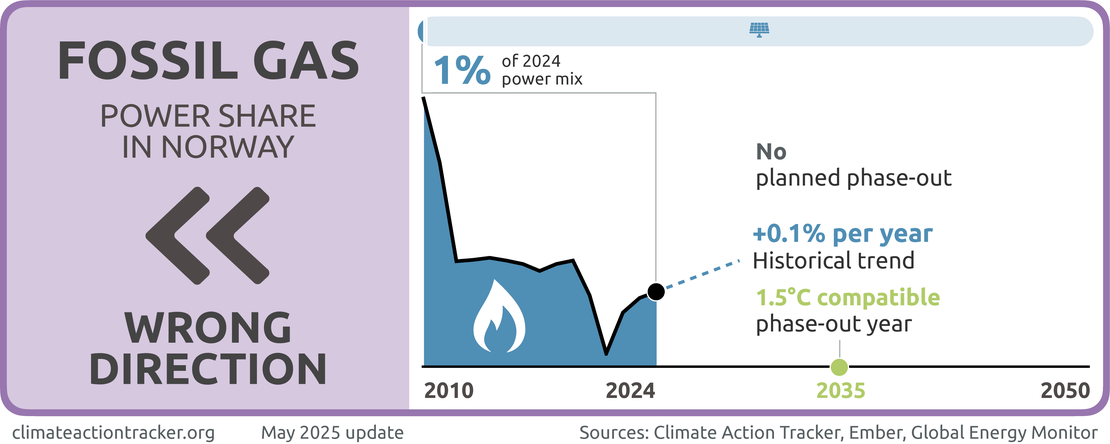

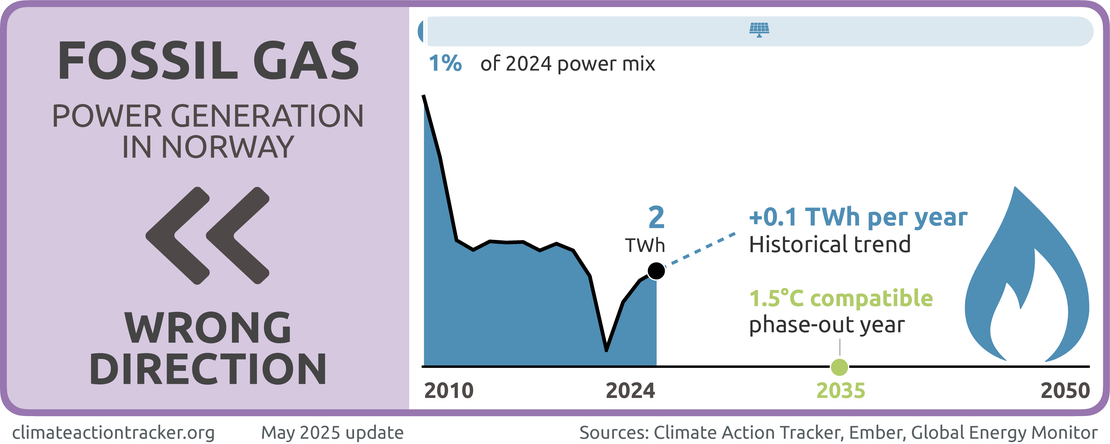

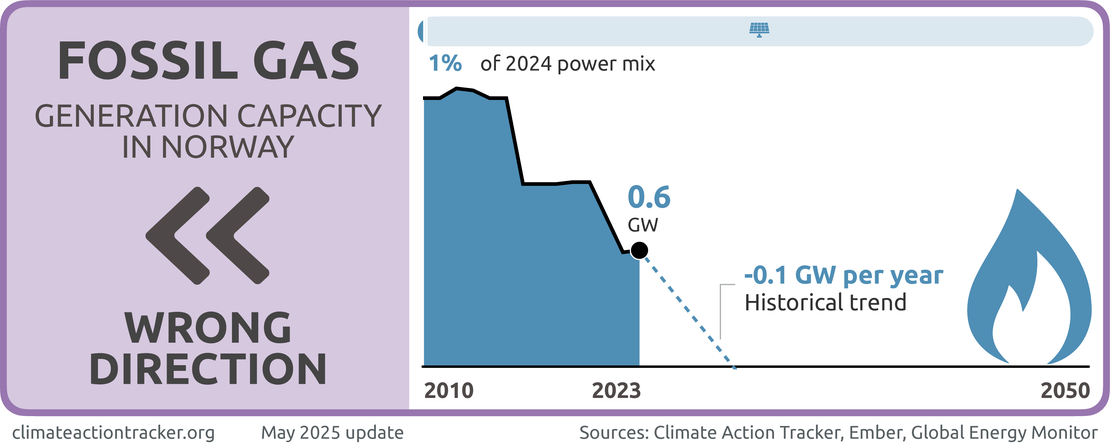

Fossil gas

Despite fossil gas representing only 1% of total power generation in Norway, we evaluate developments in this sector as moving in the “Wrong direction.” Over the last five years, Norway has increased the use of fossil gas in the share of total generation and in absolute terms. The government has also not established a target for limiting or phasing out the use of fossil gas in total power supply. To align with 1.5ºC compatible pathways, Norway needs to phase out fossil gas by 2035 at the latest; however, Norway’s 2035 NDC does not commit to a timeline for phasing out fossil fuels.

Our full analysis of the 2035 target can be found here.

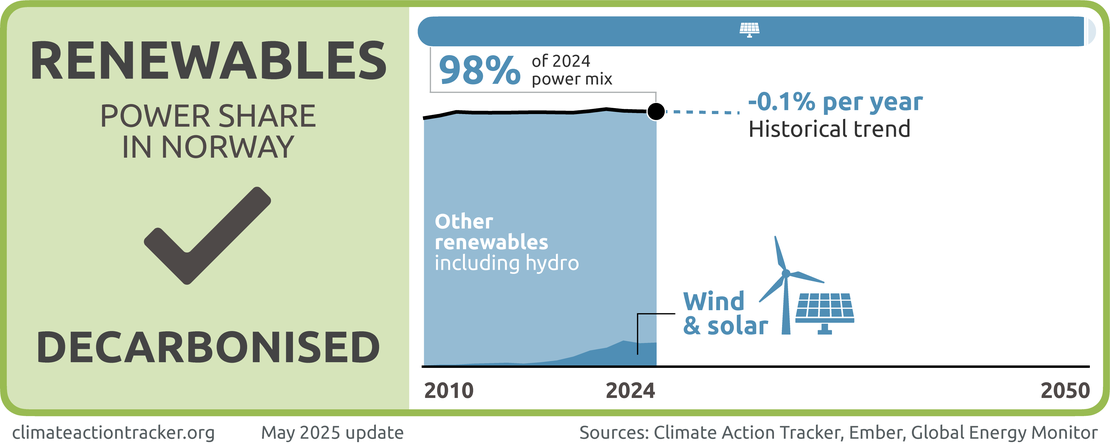

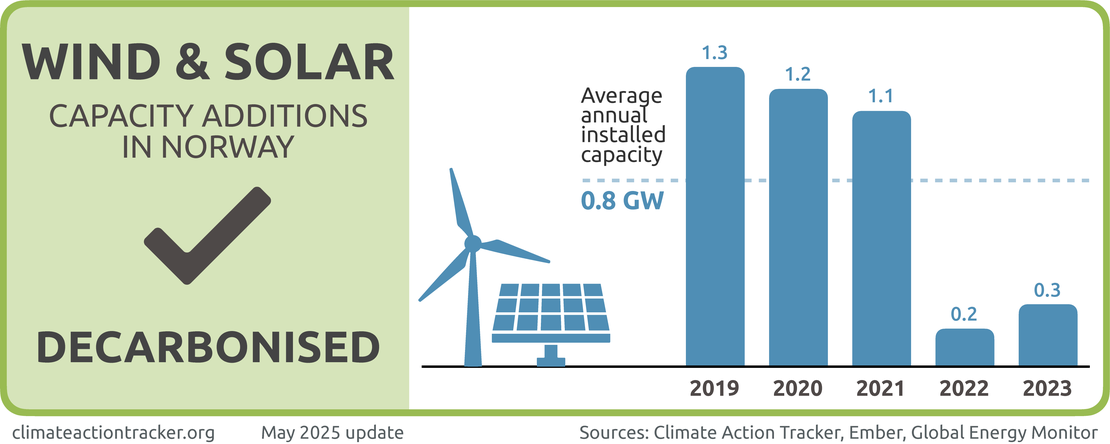

Renewables

We evaluate Norway’s progress on renewables as “Decarbonised” because renewable sources make up over 98% of total power generation. While generation from hydroelectric power plants has remained stagnant, wind and solar have seen growth in their shares of both total and absolute power generation over the last five years.

Hydrogen

In December 2021, Norway’s state-owned climate investment body, Enova, announced an investment of EUR 100 m in clean hydrogen production for three separate industrial projects. Just under three-quarters of the funding was to be directed towards producing “blue hydrogen” from fossil gas with carbon capture and storage (Bellona, 2021).

However, four years later the situation has unfolded somewhat differently. Despite a memorandum of understanding with Germany that contemplated the large-scale export of Enova’s blue hydrogen, Enova scrapped the planned investment in September 2024, citing rising costs and insufficient demand (Reuters, 2024).

Carbon tax

Norway is home to the largest hydrocarbon reserves in Europe and is the world’s fifth largest exporter of crude oil. Its offshore drilling activities have been subject to a carbon tax since 1991 (EIA, 2024). In 1999, the carbon tax was increased, and in 2005 Norway joined the EU ETS.

By 2023, around 83% of greenhouse gas emissions were subject to a net positive Effective Carbon Rate (ECR), with carbon taxes also applied to domestic aviation and mineral oil (OECD, 2024). In January 2021, the Norwegian government announced plans to gradually raise its carbon tax until it reaches NOK 2,000 (USD 220) by 2030. The 2025 rate stands at NOK 944 (USD 93) per tonne.

In July 2025, the Ministry of Finance decided to end the fuel excise tax exemption for Norwegian fishing vessels sailing abroad, incentivising the domestic fishing fleet to refuel in places like the Shetland or Faroe Islands (McBride, 2025). The decision led to 1.5 million litres of cancelled fuel orders on 2 July 2025. Critics argue that while the tax on fishing vessels was intended to begin the transition to cleaner fuels, such alternatives remain unrealistic for a large share of the fleet and neighbouring countries, such as Denmark, compensate both domestic and foreign fishers for 100% of their carbon tax, creating a competitive disadvantage for Norway (McBride, 2025). More work will need to be done to develop a path to decarbonising both the Norwegian and broader European fishing industries that ensures a fair and equitable transition for all involved.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS)

Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) refers to technologies which use engineered methods to capture CO2 from a source and store it geologically. CCS can be applied to a range of different CO2 sources in different sectors. Through higher taxes, investments in CCS have been viable in Norway since 1996, after which nearly 1 MtCO2 a year has been captured from the Sleipner Vest oil field (Norsk Petroleum, 2024).

The Norwegian Government has supported investment in CCS projects by setting aside NOK 80 million (USD 9.6 m) in 2018 to fund Front End Engineering and Design (FEED) studies (Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, 2018). In 2019, Norway’s Ministry of Oil granted a license to the country’s main state-owned oil and gas company, Equinor (formerly Statoil), to develop CCS capabilities, aiming to capture around 1.5 MtCO2 annually from onshore installations (Reuters, 2019). In 2024, Norwegian Minister of Energy Terje Aasland conducted the opening ceremony for the Northern Lights CO2 transport and storage facility in Bergen, which claims it will have a first phase capacity of 1.5 MtCO2 per year (Equinor, 2024).

However, there are reasons to doubt whether these individual CCS projects can be described as successful models for global decarbonisation. Research conducted by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis found that storing carbon dioxide underground may carry more risk and uncertainty than drilling for oil and gas, due to a lack of technical experience and the unique challenges that come with each storage site’s geology (Hauber, 2023).

After just three years of operation, in 1999 the Sleipnir CCS project experienced unexpected problems when the carbon dioxide injected below ground began rising to the upper levels of the storage formation (Hauber, 2023). If the upper layer had not been naturally bounded by geologic formations, the stored CO2 could have escaped, damaging the integrity of the project and requiring costly repairs.

The same issue arose with a CCS project at Snøhvit just 18 months after work began, despite detailed pre-operation field assessments (Hauber, 2023). The Snøhvit site was believed to offer 18 years of carbon storage capacity, but after signs that the underlying geological formation was failing to store carbon, this estimate was reduced to 2 years. The unexpected failure threatened USD 7 bn of investments and required emergency action and long-term alternatives to solve the problem, both deployed at significant cost (Hauber, 2023).

Due to the uncertainty surrounding its technical and financial viability, and the significant costs of establishing, operating, and monitoring storage projects, CCS should be limited to industrial applications where there are fewer options to reduce process emissions, rather than in the electricity sector where deploying renewables is a more effective, cost-competitive, and longer-term way to reduce emissions.

Industry

Emissions from the industry sector contributed one-quarter of Norway’s total emissions in 2024. Industrial emissions play a much more important role in Norway than in many other countries as a result of Norway’s large oil and gas extraction sector (Norsk Petroleum, 2025a). In 2024, the oil and gas sector constituted around 60% of Norway’s exports (Statistics Norway, 2025). Such a heavy reliance on fossil fuel exports places Norway’s economy at risk given the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C temperature limit, which is a strong impetus to diversify away from oil and gas production.

Oil and gas production

Norway was the third largest exporter of fossil gas in the world in 2021, with over 94% of its annual production exported for consumption abroad (EIA, 2022). After Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine disrupted gas lines in 2022, Norway surged to become Europe’s top supplier of fossil gas, providing 30% of fossil gas imports and nearly 10% of the continent’s total energy consumption (Gassco, 2025b). In 2024, Norwegian exports of fossil gas hit record numbers in six of the year’s 12 months.

In the decade leading up to 2022, the Norwegian government awarded more than 700 oil and gas exploration licenses, more than in the previous 47 years (Oil Change International, 2022). These licenses represent 2.8 bn barrels of new oil and gas resources. If development of oilfields already licensed but not yet producing is permitted, an additional 3 GtCO2e could be emitted abroad.

In January 2025, Norway awarded 53 licenses for oil and gas exploration to 20 companies, with Minister of Energy Terje Aasland arguing that further drilling is necessary to sustain Norway’s fossil fuel output (Buli, 2025). However, while the success rate for exploration wells on the Norwegian continental shelf remains high, the average size of discovered oil and gas reserves has been falling. In 2024, Norwegian exploration drilling increased by 24% over the previous year, but yielded 24% less in discovered oil and gas volumes (Coleman, 2025). This is yet another warning sign that oil and gas production is unsustainable and economically non-viable in the long term.

With no plans to phase out fossil fuels, the Norwegian Offshore Directorate reported in May 2025 that oil production is already higher than the annual forecast, coming on the heels of a record-breaking year for fossil gas production in 2024 (Norsk Petroleum, 2025b; Norwegian Offshore Directorate, 2025). As fossil fuel production increases, investments in oil and gas are also projected to hit a record high of nearly USD 27 bn in 2025 (Jacobsen & Adomaitis, 2025).

These developments stand in stark contrast to the fact that oil and gas production should already be declining to be 1.5°C compatible. As one of the world’s most advanced economies that has significantly benefited from oil and gas revenues, Norway should lead by example and immediately end new oil and gas investments and adopt a clear plan to phase out existing oil and gas production.

Climate litigation

In 2022, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) decided to hear a case challenging Norway’s plans for new oil and gas drilling in the Barents Sea (Schwartzkopff, 2022). The case charged that approval of such permits would constitute a breach of fundamental human rights. In October 2025, the ECtHR rejected the case but affirmed that Norway must assess the global impact of emissions when awarding new licenses for oil and gas drilling (Adomaitis, 2025).

In a groundbreaking development for climate litigation, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague, Netherlands, issued an advisory opinion in July 2025, stating that states have a legal obligation to protect the environment and limit greenhouse gas emissions (UN News, 2025). The ICJ ruled further that breaching this obligation brings legal responsibility and states may be forced to stop their polluting conduct and repair the damage caused by their emissions. While it is not yet certain how legal systems around the world may apply this new ruling, it is a powerful reminder for petrostates like Norway that continuing to rely on fossil fuels is not just expensive, unsustainable, and harmful, but it may be illegal.

Transport

Sales of electric vehicles (EVs) in Norway have accelerated tremendously over the past decade, from accounting for less than 1% of total sales in 2010 to nearly 90% in 2024 (Meredith, 2025). As of November 2025, EVs represent nearly 98% of all new cars sold in Norway (Mannes, 2025). Norway’s National Transport Plan (NTP) 2022-2023 outlined a target of all new passenger cars and light vans being zero-emission vehicles by 2025 (Norwegian Ministry of Transport, 2021); recent trends suggest Norway is very close to meeting this goal: a world first.

While electrification of the commercial fleet is lagging behind, with only 29.6% of vehicles being zero-emission in 2024, this represents a 20% increase over just five years and highlights Norway’s accelerating action in the transport sector (Norwegian EV Association, 2024). At COP26 in Glasgow, signatories of the 100% EVs declaration agreed that 100% of new car and van sales in 2040 should be electric vehicles, 2035 for leading markets, leaving Norway in a strong position to meet its pledge (Accelerating to Zero Coalition, 2021).

The NTP also includes a target to reduce transport emissions by 50% below 2005 levels by 2030 (36% below 1990 levels). However, according to Norway’s latest National Inventory, transport emissions only decreased by about 7% from 2005 to 2023 (Government of Norway, 2025a). To meet the target outlined in the NTP, transport emissions would need to fall by 46% from 2023 levels by 2030, a significant decrease that will require more ambitious action. Since the power sector is largely decarbonised, Norway has been focusing more on reducing emissions in the transport sector to align its emissions reductions rates with the EU’s target.

Norway has also announced that new city buses will be zero-emissions or run on biogas by 2025 (Norwegian Ministry of Transport, 2021), while 75% of heavy-duty vehicles will be renewable by 2030 (Meredith, 2025). In 2023, 1,415 electric buses were part of the Norwegian fleet, up from just 840 in 2022, representing a 68.5% year-over-year increase (Salas, 2025). As of 2024, 85% of kilometres travelled by public buses in Oslo are fully electric, up from 0% in 2018 (EuroCities, 2025). While more work remains, such rapid electrification is a very positive indicator for progress in the transport sector.

Electrification is also planned for railways, substituting old diesel-fuelled lines to reduce emissions. New electrified lines are faster, and more cost competitive against road transport, given the country’s low electricity costs. As of 2025, 65% of Norway’s rail network has been electrified, with most improvements taking place in the more populated southern part of the country (Norway Trains, 2025). While further upgrades should focus on electrifying the northern rails, adverse weather and topographical conditions mean progress is advancing slowly.

Norway is also a pioneer in electric ferries. The Norwegian parliament passed a resolution in 2018 which called on the government to transform its fjords into a zero-emissions control area by 2026 (Brown, 2018). In 2022, the high-speed electric ferry Medstraum began servicing passengers between the city of Stavanger and its surrounding communities, a route expected to reduce emissions by 1500 MtCO2e; the equivalent of taking 60 fossil-powered buses off the road (Business Norway, 2025). Medstraum is the latest innovation from the EU-funded TrAM project, which brings together 14 European partners to develop zero-emission ferries through modular production. As a sign of its creativity and success, the TrAM project was nominated for the European Sustainable Energy Award for Innovation in 2023.

Buildings

Norway has tightened building regulations over the last two decades, resulting in direct emissions from the buildings sector decreasing by more than three-quarters between 1990 and 2019 (Climate Analytics, 2022). Norway’s aims to reduce electricity use in buildings by 10 TWh per year by 2030 below 2015 levels through a combination of stricter efficiency rules for new construction and the refurbishing for older buildings (Nordic Energy Research, 2025). In 2019, Governing Mayor of Oslo Raymond Johansen signed the Net Zero Carbon Buildings Declaration, committing Oslo to ensure that all new and old buildings in the capital will be net zero by 2050 (C40, 2019).

EU Regulations

As part of the EEA, Norway aligns its policies with EU regulations but has more flexibility with the timing and implementation of their adoption compared to EU Member States. There are four key EU policies on emissions from buildings that Norway has worked to incorporate into national law:

- The Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD), originally passed in 2010 and revised in 2024, sets minimum energy standards for new and renovated buildings, mandates energy system inspections, and promotes Zero Emission Buildings (ZEBs) (Nordic Energy Research, 2025). The 2010 version was incorporated into Norway’s EEA agreement and has been in force since 2023. The revised version sets stricter energy standards and a binding energy performance target for Member States.

- The Ecodesign Directive, adopted in 2009 and replaced by an expanded version in 2024, sets minimum energy efficiency and environmental standards for energy-related products in the EU and aims to create a circular flow of durable, reparable, and recyclable goods (Nordic Energy Research, 2025). The 2009 directive has been fully implemented in Norway since 2011.

- The Energy Labelling Framework Regulation of 2017 requires clear and consistent labels for household appliances and energy-related products (Nordic Energy Research, 2025). The regulation has been fully implemented in Norway since 2020.

- The Energy Efficiency Directive (EED), originally passed in 2012 and revised in 2023, sets binding energy-saving targets and mandates the renovation of public buildings, improvements to metering systems, and energy audits for large industrial companies (Nordic Energy Research, 2025). The older version has been derogated in Norway while adoption of the 2023 EED is being evaluated; a process still ongoing as of 2025.

While it is very positive to see Norway aligning its policies in this sector with the latest EU standards, it is important to note that several of these directives have been updated since Norway adopted them. Revised directives, such as the EPBD and new Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR), have significantly expanded their coverage and added more ambitious targets compared to their original versions. To reduce emissions from buildings, it is vital that Norway continue to update its national legislation to reflect the latest EU regulations.

Heating and Cooling

Norway has also introduced a ban on fossil fuel heating systems; specifically, oil and paraffin systems, given the unavailability of fossil gas. This ban has been phased in since 2016 and has been in full force from 2020 onwards. The ban applies to both new buildings and renovations and both private homes and public spaces of businesses and state-owned facilities (Reuters, 2017). According to Norway’s Seventh National Communication this ban will reduce emissions in the country by 400 ktCO2 in comparison to business-as-usual (Government of Norway, 2018).

By taxing carbon emissions from fossil heating systems, heat pumps have become a cost-competitive technology in Norway and domestic deployment is now booming (Niranjan, 2023). According to the IEA, heat pumps represented only 10% of the heat used in buildings worldwide in 2021, but over two-thirds of households in Norway used them for cleaner and cheaper heating in 2023 (IEA, 2022). By training their workforce in device installation and adopting national policies incentivizing and streamlining their uptake, Norway’s success with heat pumps is a model for the rest of Europe and beyond.

Agriculture

The agriculture sector accounted for about 10% of Norway’s total emissions in 2023 at 4.5 MtCO2e (Government of Norway, 2025a). Agriculture is the largest source of both methane and nitrous oxide emissions in Norway (Government of Norway, 2021b). Unfortunately, these emissions arise from complex biochemical processes across diffuse sources, such as soils, fertiliser, and livestock. Therefore, there is significant uncertainty about their exact levels. However, even low levels of methane emissions are highly damaging to the climate because of methane’s potent warming effect, which is far greater than carbon dioxide in the short-term.

The agriculture sector is one of few sectors with a sector-specific emissions reductions target in Norway’s Climate Action Plan 2021–2030 (Government of Norway, 2021b). The Norwegian government has signed a letter of intent with the two main agricultural organisations in the country, committing both parties to reduce emissions and enhance removals from agriculture by 5 MtCO2e by 2030.

Unfortunately, the Climate Action Plan 2021–2030 does not commit Norway to any specific policy measures in this sector; rather, it suggests the government will work with agricultural organisations to identify effective policy instruments, promote changes in consumption patterns, and improve emission inventories across the sector (Government of Norway, 2021b). A few measures contemplated by the plan include a tax on mineral fertiliser to reduce nitrous oxide emissions, livestock breeding programmes, improved fertiliser management, and a transition to fossil-free sources for transport and heating.

Without a clear set of policy measures, targets, and accurate inventories across the agriculture sector, it is unlikely Norway will be able to meet the goals set out in its Climate Action Plan 2021–2030.

Forestry

Norway's forests are a substantial carbon sink, amounting to approximately half of Norway’s annual emissions (Government of Norway, 2025a). Since 2010, the forest area has been gradually increasing and in 2023 reached 33.5% of Norway’s total land area, compared to 33.1% more than a decade earlier (World Bank Group, 2023). Norway signed the forestry pledge at COP26, where leaders agreed to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030 (UN Climate Change Conference UK, 2021).

In its latest LULUCF projections, the Norwegian government estimates the available carbon sink in 2030 to be about half the size it was in 2010, emphasising the importance of real emissions reductions rather than reliance on declining removals (Government of Norway, 2025b, 2025a). As part of its Climate Action Plan 2021-2030, Norway committed to introduce a minimum logging age in its Forestry Act in line with the latest PEFC Forest Standard and to facilitate the afforestation of new land, although no quantitative targets have been set (Government of Norway, 2021b).

In addition, Norway has pledged up to USD 343m per year in the framework of the Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative (NICFI) to reduce deforestation in other countries, which was recently extended to 2035 (Government of Norway, 2018, 2024b).

Waste

Emissions from the waste sector accounted for about 3% of Norway’s overall emissions in 2023 at 1.4 MtCO2e (Government of Norway, 2025a). The largest source of emissions in this sector is the disposal of solid waste, either through carbon dioxide released during waste incineration or methane leakage from landfill storage. Although waste emissions have declined nearly 50% from their 1990 levels, this sector is a significant source of methane emissions and further action must ensure that these emissions are properly measured and mitigated.

Similar to the transport, building, and agriculture sectors, emissions from the waste sector are not covered under Norway’s participation in the EU ETS and therefore must be reduced through domestic action (European Commission, 2025c). The most detailed mitigation strategy for the waste sector included in Norway’s Climate Action Plan 2021–2030 is the use of organic waste to produce biogas (Government of Norway, 2021b). Such biogas production contributes to Norway’s goals of establishing circular patterns of resource use by turning waste products into new outputs for clean commercial fuels for road and maritime transport.

The landfilling of organic waste has been banned in Norway since 2009 due to its high potential for methane leakage (Government of Norway, 2021b). The digestate left behind by the production of biogas can also be used as a nutrient-rich fertiliser, returning critical minerals like potassium, phosphorus, and nitrogen to the soil to aid plant growth and enhance carbon uptake. Norway also instituted new requirements in 2024 for biofuels made from organic waste, mandating a 19% rate for transport fuels, which the government may increase further as the carbon tax makes alternative fuels even more cost-competitive (Government of Norway, 2021b).

Methane

Norway signed the methane pledge at COP26, which is significant given its large oil and gas sector and the resulting methane emissions. A commitment to reduce methane emissions has not, however, been included in Norway’s NDC submissions for 2030 or 2035, despite making up 10% of Norway’s total emissions in 2020 (Government of Norway, 2022a). Signatories agreed to cut methane emissions in all sectors by 30% globally over the next decade.

A 30% reduction in methane emissions below 2020 levels would represent a decline of 1.6 MtCO2e. Two existing measures—a 2009 regulation prohibiting the landfilling of organic waste and a 2002 directive mandating the extraction of methane gas from landfills with organic waste—led to a 53% reduction in methane emissions from landfills between 1990 and 2020 (Government of Norway, 2020a, 2022a).

The majority of methane emissions in Norway come from the agricultural sector, which contributes 55% of all methane emissions (Government of Norway, 2023). This methane is primarily released by enteric fermentation, a digestive process occurring in ruminants like sheep and cattle. While Norway’s Climate Action Plan 2021–2030 suggests the government will work with agricultural organisations to reduce methane emissions in this sector, it does not commit to a specific policy pathway (Government of Norway, 2021b). Given agriculture’s significant contribution to methane in Norway, the government should take ambitious action and develop a plan to reduce its emissions.

At COP27, Norway announced along with the US, EU, and other countries the Joint Declaration from Energy Importers and Exporters on Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Fossil Fuels, which reinforces the Global Methane Pledge. The joint declaration outlines the intention to adopt further policies and measure to reduce methane emissions along the supply chain of fossil fuel trade.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter