Policies & action

Russia’s efforts to tackle climate change are deficient. Under current policies, Russia’s economy-wide emissions are expected to either flatline or continue rising to 2030, when they should be rapidly declining.

In June 2021 Russia adopted its heavily watered-down climate bill that, unlike the original iteration of the legislation, does not enforce emissions quotas nor impose penalties on large GHG emitters. Instead, its main provision simply requires companies to report their emissions from 2023. Considerable uncertainty remains in Russia’s renewable energy sector, with no targets in place beyond its very modest non-hydro generation target of 4.5% by 2024.

Mandatory energy efficiency standards for new buildings were abolished in 2020 and replaced with mandates on automated heating controls and bans on particular inefficient heating systems. It is not clear whether these measures will achieve the efficiency standards of the previous legislation. Action in the transport sector remains very limited, with next to no electric vehicles sold in Russia in 2020 and no plans to target emissions from heavy duty vehicles.

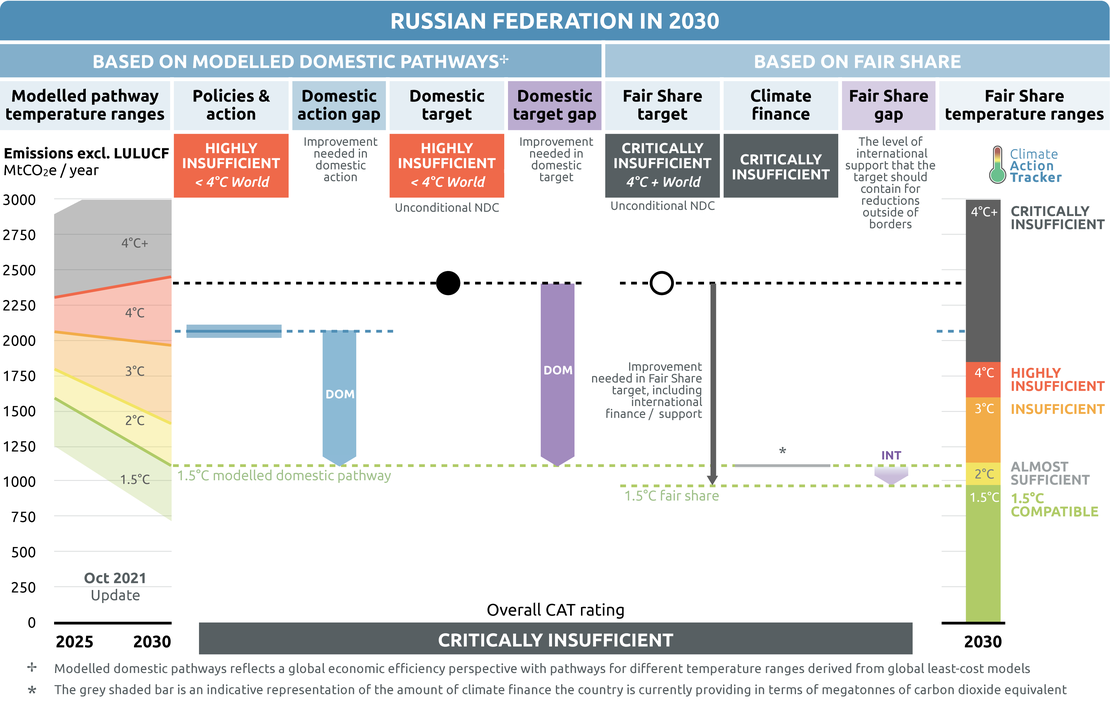

The CAT rates Russia’s current policies as “Highly insufficient” when compared to modelled domestic pathways. The “Highly insufficient” rating indicates that Russia’s policies and actions are not at all consistent with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C temperature limit. If all countries were to follow Russia’s approach, warming could reach over 3°C and up to 4°C.

Policy overview

Contrary to the required peak and decline of emissions needed to achieve the Paris Agreement goal, emissions in the Russian Federation are expected to either flatline or continue growing from 2021, after the expected economic recovery-induced increase, until at least 2030.

Russia’s 2030 emissions target, which uses 1990 as a reference, allows national emissions to continue an upward trend. According to our latest estimates, currently implemented policies would lead to emissions between 2.0 and 2.1 GtCO2e in 2030 (excluding LULUCF), which is just 0.1–5% below 2019 emission levels. This represents a 33–36% decrease in emissions below 1990 levels, a level that is below the NDC target for that year, which amounts to a 24% decrease below 1990 levels (excluding LULUCF).

Draft long-term strategy and net zero target

In March 2020, Russia released its draft long-term climate strategy, which contains emissions projections to 2050 (Russian Federation, 2020a). Both the “baseline” and more ambitious “intensive” emission projection scenarios fail to realise a reduction in emissions below 2017 levels by 2050, representing a severe lack of ambition from the Russian government. According to the IPCC Special Report on 1.5°C, the world must achieve net zero CO2 emissions by 2050 to limit warming to the 1.5°C long-term temperature goal of the Paris Agreement (IPCC, 2018). This demonstrates the extent to which Russia’s projected emissions trajectories fail to live up to the level of ambition required, which is of particular concern given it is one of the world’s major emitters. In October 2021 Russia announced that it will achieve net zero emissions by 2060, a crucial step on the path to Paris Agreement compatibility, but at the time of writing, it has not been formally adopted, nor accompanied by details of how it will be achieved. It is also not clear whether the target covers all GHG emissions or CO2 emissions only.

Reports have emerged of an amended draft long-term strategy under consideration that outlines a 79% reduction in CO2 emissions below 2019 levels by 2050 under its main “target” scenario (Reuters, 2021). This could place Russia on a path to achieving the announced net zero by 2060 target.

Russia’s existing draft long-term strategy includes a list of policy actions required to achieve its stated priority of aligning with the Paris Agreement, including the creation of economic incentives to reduce GHG emissions, systematic replacement of inefficient technologies, and creating conditions to ensure Russian companies are competitive in emerging low-carbon development markets (Russian Federation, 2020a). At present, there is little to no action being undertaken on any of these stated policy requirements. If Russia is to align itself with the goals of the Paris Agreement, as it has stated it intends to, significant action in these areas and others will be required.

Recent legislative developments

Key climate legislation aimed at limiting greenhouse gas emissions introduced in December 2018 was initially intended to establish a cap-and-trade system for major carbon emitters by 2025 and require companies to report their emissions. It would have allowed the government to introduce targets for GHG emissions and charge companies for excess emissions, which would feed into the Emissions Reduction Support Fund. However, due to resistance from the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs, all of these measures, except for the requirement of companies to report their emissions, were removed (Moscow Times, 2019b). The legislation was passed in June 2021 with all originally proposed targets and penalties for large emitters omitted, ensuring it will have very limited impact on Russia’s future emissions.

Russia released its Draft Energy Efficiency Action Plan in 2021, which includes targets for improving the existing housing stock, energy standards for new buildings, and slight to moderate improvements in the efficiency of cast iron and cement production (Russian Federation, 2020f). The measures targeting the building sector, however, replace abolished energy standards that were likely to result in higher overall emission reductions.

Risks to the Russian economy

Russia’s heavy reliance on fossil fuel revenues leaves the Russian economy at risk of significant losses in the event of a rapid decline in global fossil fuel demand as required by the goal of the Paris Agreement. Two recent studies have shown the potential impact on Russia’s economy under a scenario of concerted global climate action. Kahn et al., (2019) estimate that Russia’s GDP per capita could be up to 0.6% lower by 2050, while Makarov, Chen, & Paltsev, (2020) project that such concerted action from the main importers of Russia’s fossil fuels will reduce Russia’s GDP growth rate by half a percentage point. Makarov, Chen, and Paltsev not only found that the Paris Agreement is expected to raise the risks of Russia facing market barriers to exporting its energy-intensive goods, but that redistribution of income from the energy sector would benefit the economy.

The EU’s proposed Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which seeks to place a levy on carbon intensive goods, is likely to have a sizeable impact on Russian exports, with a recent study estimating Russia will face higher costs from the proposed mechanism than any other country (Assous et al., 2021). The EU is Russia’s largest trading partner, and without implementing significant measures aimed at decarbonising the Russian industry sector, these economic costs are likely to climb over time.

Impacts of climate change

Russia’s continued reliance on emissions-intensive forms of energy not only poses a challenge for the Russian economy in the future, it is also expected to exacerbate the impacts it faces from the changing climate. The 900-page report “On the status and protection Environment Russian Federation” produced by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Ecology breaks down the past and future consequences of climate change for the country (Ministry of Natural Resources and Ecology of the Russian Federation, 2017). It concludes that Russia is already being hit by the natural disasters and other impacts of climate change, and projects this trend to increase in the future (e.g. heatwaves, widespread forest fires, epidemics, drought, mass flooding, and food shortages). This was underscored by Russia’s climate adaptation plan for the period to 2022, released in January 2020. In addition to the aforementioned impacts, it projects an increased risk to public health, degradation of permafrost in the northern regions with damage to buildings and communications, disruption of the ecological balance, including the displacement of some species by others, and the spread of infectious diseases and parasites (Russian Federation, 2019a).

Energy supply

Russia’s energy sector accounted for nearly 80% of all emissions without LULUCF in 2019 (the last year for which data is available) (IEA, 2020a).

Energy Strategy to 2035

In June 2020, Russia adopted its long-delayed Energy Strategy 2035, confirming Russia’s intention to heavily support its fossil fuel energy sectors beyond the next decade (Russian Federation, 2020b). The strategy suggests that Russia will continue to sell oil, coal, and gas to the rest of the world, while everything that hinders this goal is considered to be a threat and a challenge (Zhelenin, 2020). This flies in contradiction to the IEA’s recent finding that no investments in new oil and gas extraction projects should occur beyond 2021.

Indeed, the strategy assumes that “until 2035 fossil fuels will continue to form the basis of the global energy sector with a gradual increase in the share of energy based on the use of renewable sources” (Russian Federation, 2020b). These assumptions underpin both scenarios outlined in the document, and accordingly, there is little focus on renewable energy technologies, and no long-term targeted increase in generation from this sector.

The intention behind Russia’s energy strategy has been signalled by recent government decisions supportive of fossil fuel companies. In 2021, Novatek, Russia’s largest independent natural gas producer, requested access to more gas resources to support the construction of its third large-scale gas facility since 2017 (Persily, 2021). The gas deposits Novatek wanted access to were within the boundaries of a natural reserve where industrial activities are prohibited, but after reportedly requesting that the Kremlin instruct the regional government to adjust the boundaries to allow the facility to proceed, the regional government obliged in May 2021 and the boundaries were changed. In addition, President Putin in August 2021 ordered the introduction of amendments designed to allow Russian Railways and coal miners to agree on expanding eastward coal exports.

Other key elements of Russia’s energy strategy include advocating for the development of clean-coal technology and for minimising the flaring of natural gas as key measures to address climate change in the energy sector.

Natural gas and flaring emissions

Despite a stated goal of minimising flaring, and the introduction in 2012 of a 5% limit on flaring of gas as a proportion of total production, the figure in 2016 remained close to 11% (Korppoo, 2018). In 2020, Russia saw its third consecutive year of increasing flaring volumes, maintaining its position as the world’s largest gas flaring nation (Global Gas Flaring Reduction Partnership, 2021). At 25 billion cubic metres, Russia flared over 40% more gas in 2020 than the next highest country, Iraq.

Natural gas made up 54% of Russia’s total primary energy demand in 2020, and this is projected to increase slightly to 55% by 2030 under current policies, mostly at the expense of coal (IEA, 2019b). This high share of gas is problematic, as gas does not have a place in 1.5°C compatible scenarios and still produces significant GHG emissions in both its production and consumption (IPCC, 2018).

Gas share

Fossil fuel finance and risks to the Russian economy

The current and projected future high reliance of the Russian economy on the fossil fuel sector is not without risk. Even before the massive decline in global oil demand caused by the COVID-19 related economic slowdown in early 2020, Russia and Saudi Arabia were already fighting an oil price war (S&P Global Platts, 2020). Russia refused to reduce oil output to keep global prices afloat, and in response, Saudi Arabia drastically increased supply, sending oil prices plummeting. This large oil price shock and the numerous others before it, demonstrate the potential volatility inherent to Russia’s strategy of relying on fossil fuel export revenues for economic growth and fiscal stability. Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Russian energy exports and budget revenues were projected by one study to decrease by 15% and 17% below 2019 levels respectively by 2040 under its “energy transition” scenario (Mitrova et al., 2020). Conversely, the latest projections from the Russian government show oil, gas and coal exports all increasing to 2030 (Russian Federation, 2019b).

There are increasing signs of reticence from the banking sector to finance projects seen as contributing to climate change. A number of Western commercial banks have recently announced policies against providing financing for oil and gas projects in the Arctic, while in late 2019, the European Investment Bank announced a total ban on funding fossil fuel projects by the end of 2021 (Associated Press, 2020; Ekblom, 2019). A continuation of this trend will increase the risk that the envisaged expansion of Russia’s fossil fuel exports fails to eventuate, with substantial negative implications for Russia’s public finances.

In a sign that environmental concerns of investors may also be affecting corporate behaviour in Russia, Enel Russia, a large Italian-owned energy retailer, sold off its largest coal power station in 2019 (Moscow Times, 2019a). Enel Russia is a leading investor in renewable energy and has been attempting to divest itself of coal-fired power assets in order to make its portfolio of power plants greener.

In contrast, Russian state development bank VEB said in November 2019 that it would provide financing of 34 billion roubles (USD 32m) together with VTB Bank for the construction of a new coal port in the east of Russia (Reuters, 2019). The terminal’s initial capacity is expected to be 12 million tonnes of coal per year, eventually doubling to 24 million tonnes per year. Operations are scheduled to commence at the port in late 2021 (AK&M, 2020).

Coal share in energy supply in Primary Energy

Renewable energy

Installed renewable power generation capacity sat at approximately 57 GW by the end of 2019, equivalent to 21% of the country’s total power generation capacity, with hydropower representing by far the majority of the installed renewable energy capacity (54 GW).

A recent positive development is Russia’s decision in late 2019 to extend the support programme for renewable energy beyond 2024, with 400 billion roubles (5.6 billion USD) allocated to construct 5.3 GW of renewable energy capacity between 2025 and 2035 (Lyrchikova, 2019). This is roughly double the 2024 renewable energy capacity target under the previous scheme of 5.6 GW. The funding split under the new programme is to be 60% towards wind energy projects, and 40% towards solar PV projects, resulting in 3 GW and 2.2 GW of new wind and solar PV capacity respectively.

Under current policy projections, there is a slight upward trend in the share of renewable sources in primary energy demand, from around 3.3% in 2017 to 4.5% by 2030. Russia has a 2.5% renewable energy target for 2020 and a 4.5% target for 2024 (excluding large hydropower) for the electricity sector, which we estimate would increase the share of renewable energy sources slightly to 4.5% of primary energy demand by 2030. However, in 2019, just 0.16% of Russia’s electricity came from non-hydro renewables compared to the global average of over 10%, indicating it is very unlikely Russia will meet even its modest short-term renewable energy targets (BP, 2020). The lack of projected progress on increasing uptake of renewable energy in Russia is shown below. This includes generation from large hydro.

Share of renewable electricity generation

Transport

The bulk of Russia’s efforts to decarbonise its transport sector relate to its rail infrastructure. This includes the Russian Railway’s long-term investment strategy to 2025, and the Strategy for Development of Rail Transport 2030. Some of the measures outlined include investments in high-speed rail, improving the capacity of the freight network, 16,000 km of new rail routes, and a planned 33% increase in passenger numbers between 2008 and 2030 (Russian Federation, 2014c; Russian Railways, 2008). Russia’s draft long-term climate strategy includes a commitment to achieve a modal shift for passenger and cargo transport to less carbon intensive modes of transport (Russian Federation, 2020a).

Measures targeting other areas, however, are still lacking; there are no plans to phase out sales of fossil fuel passenger cars or heavy duty vehicles, while there are also no fuel efficiency standards in place. Less than 700 electric vehicles (EVs) were sold in Russia in 2020, something the government is attempting to remedy with a recently released electric vehicle “concept”. This concept targets the construction of 9,400 charging stations and local manufacturing of at least 25,000 EVs by 2024, reaching at least 72,000 charging stations and a 10% EV share of total vehicle manufacturing by 2030 (Baker McKenzie, 2021).

Buildings

Russia has taken steps backwards when it comes to buildings decarbonisation, with a previous regulation mandating efficiency gains in new buildings scrapped in 2020 (Russian Federation, 2020d). In its draft Energy Efficiency Action Plan released in 2020, automated heating controls and energy efficiency surveys for new buildings are proposed to be mandatory, along with a proposal to ban certain inefficient heating systems. The effect of these proposed measures, however, is unclear and appear unlikely to achieve the previously mandated efficiency gains (Russian Federation, 2020c).

The draft action plan also targets a minimum energy efficiency C-rating for all renovations from 2022 and subsidies to incentivise uptake, but does not target a specific renovation rate.

Agriculture

Russia’s agricultural sector in 2019 only amounted to 5.4% of total emissions without LULUCF (Government of Russia, 2021). In the agriculture and forestry sectors, Russia’s approach is primarily based on adaptation instead of mitigation. The government has implemented a series of measures to address the negative effects of extreme weather events and disasters, including drought and fires, and is currently working on expanding the scope of its agricultural climate policies to include the use of new technologies, including new forms of nitrogen fertilisers (Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, 2017).

Negative emissions from Russia’s forestry sector equalled 25% of the country’s total emissions excluding LULUCF in 2019, reaching 535 MtCO2e (Government of Russia, 2021). The Federal Forestry Agency has developed the State Program of forestry development for 2020 (Rosleskhoz, 2013), which includes optimisation practices for afforestation and an improved methodology for risk calculation to minimise the effects of forest and peat fires.

Despite these policies, according to the most recent projections to 2050, included in the Third Biennial Report, instead of increasing, the current net forestry sink will drop to zero over the next 40 years, mostly due to the reduction in the absorbing capacity of aging forests (Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, 2017). This decline can only be halted with radical changes in forestry practices and by protecting significant amounts of primary forests from commercial clear-cutting (Kokorin & Korppoo, 2017). Such a decline in forestry emissions would make the government’s 2060 net zero emissions target very difficult to achieve.

Recently, Russia’s Environment Ministry announced it would be changing the accounting method it uses for calculating the size of Russia’s forestry sink, intending to include unmanaged “reserve” forests alongside managed forests. This violates a key element of international climate reporting, with the UN’s IPCC guidelines stating that only managed forests may be included in carbon accounting practices (IPCC, 2006). The Ministry claims that enacting this accounting change could increase absorption by almost half a billion tonnes of CO2 annually (Russian Federation, 2021). It would also, assumedly, include the largescale emissions caused by forest fires that have been intensifying in recent years due to unprecedented heat waves in Northern regions, including a record 18m ha of forest destroyed in 2021 alone.

In the national project “Ecology” (Экология) 151 billion roubles (2.1 billion USD) have been allocated for the “Preservation of Forests” for the period 2019–2024. The main focus of the policy is on the restoration of deforested land, with an aim to achieve 619 kha of reforestation and afforestation (Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, 2020). The impact of these plans on emissions is unclear and has not been included in our current policy projections.

Waste

The waste sector contributed 4.7% to Russia’s total emissions excluding LULUCF in 2019, the last year for which data is available (Government of Russia, 2021). Measures to curb emissions in the waste sector included in our projections are in line with the integrated management strategies for municipal solid waste, adopted through strategic legal documents between 2014 and 2017 (Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, 2017).

In the national project “Ecology” (Экология) 457 billion RUB (6.4 billion USD) have been allocated for "waste management", of which 296 billion RUB (4.1 billion USD) has been designated for the creation of an integrated waste management system. Other areas include the reclamation of 191 landfills and the creation of infrastructure for hazardous waste management. The impact of these plans on emissions in unclear and has not been included in our current policy projections.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter