Country summary

Overview

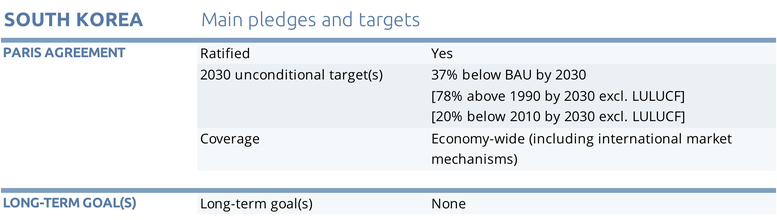

NDC update: In December 2020, South Korea submitted an updated NDC. Our analysis of its new proposed target is here.

The “Green New Deal” announced on 14 July 2020 by President Moon Jae-In did not include what South Korea’s ruling party promised during the general election campaign: no net zero emissions target by 2050, no carbon tax, and no commitment to end financing coal power plants overseas. It remains to be seen whether these targets would be adopted by the government in the coming months. Of even more concern is that the government continues to support new coal power constructions both domestically and internationally, and recently bailed out a major coal plant manufacturer.

Our analysis on South Korea’s existing measures suggests that the country is highly likely to miss its very weak Paris Agreement 2030 target (NDC), which would only reduce the nation’s emissions by 24% below 2017 levels. This level of action is nowhere near achieving the emissions reductions necessary to limit warming to 2°C, let alone 1.5°C as per the Paris Agreement. Therefore, the CAT rates South Korea’s 2030 target under the Paris Agreement as well as its existing climate measures as “Highly Insufficient”: if all countries were to follow South Korea’s approach, warming could reach over 3°C and up to 4°C.

It is expected that emissions will be about 4% to 6% lower in 2020 than in 2019 as a result of the global pandemic. While it is challenging to project the eventual impact of the COVID-19 crisis on future emissions, the CAT estimates that the South Korea’s emissions may stagnate and even slightly decrease towards 2030, a trend that could be further strengthened by more stringent climate policies.

While the current ruling party of South Korea publicly committed during April’s general election campaign to stop financing coal, introduce a carbon tax, and boost the development of renewables as part of its “Green New Deal”, except for renewables support, these were not adopted in the final New Deal package. While the strengthened support for hydrogen and electric vehicles is important for decarbonisation, the South Korean government did not commit to a phase-out timeline for internal combustion vehicles. The government also continues supporting new coal power constructions both domestically and internationally, and recently bailed out a major coal plant manufacturer, Doosan Heavy Industries.

The latest energy policy of South Korea (the third Energy Master Plan up to 2040) adopted in June 2019, together with the 2017 power sector plan for the period up to 2030, aims to increase the renewable electricity share to 20% by 2030 and 30% to 35% by 2040–up from 3% in 2017. The government has yet to commit to a complete phase-out of its coal-fired power plants. The draft ninth electricity plan contains a significantly more ambitious renewable electricity target.

In our December 2019 assessment the Climate Action Tracker projected that, without a stronger policy aligned with the recently-proposed 2050 net zero target, South Korea will even fall short of reaching its 20% renewable energy share by 2030. This will leave the country heavily dependent on fossil fuels, meaning it could only stabilise the growth of emissions, but not decrease them.

Currently implemented policies are estimated to lead to an emissions level of 665 to 743 MtCO2e/year in 2030 (‑7% to 4% in relative to 2017 levels, that is 123% to 150% above 1990 levels) depending on the eventual impact of the COVID-19 crisis, excluding emissions from land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF).

South Korea currently commits, in its NDC, to achieving 539 MtCO2e/year excluding LULUCF To reach this target, South Korea will have to significantly strengthen its climate policies, even more so if the government is serious about achieving carbon neutrality by 2050, including revising and improving its 2030 NDC to be consistent with the Paris Agreement.

The CAT rates the existing target as well as the existing measures of South Korea under the Paris Agreement “Highly Insufficient”, as it is not stringent enough to limit warming to 2°C, let alone 1.5˚C.

Currently implemented policies are estimated to lead to emissions levels of 665-743 MtCO2e/year in 2030 (‑7% to +4% relative to 2017 levels, 123% to 150% above 1990 levels) depending on the eventual impact of the COVID-19 crisis, and excluding emissions from land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF).

South Korea currently commits, in its NDC, to achieve 539 MtCO2e/year excluding LULUCF (81% above 1990 emission levels, 24% below 2017 levels) if their target that was originally based on the IPCC SAR GWPs is converted to AR4 GWPs. To reach this target, South Korea will have to significantly strengthen its climate policies, even more so if the government actually aims to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, including by revising its 2030 NDC to be consistent with the Paris Agreement.

For the power sector, the impact of the Eighth Electricity Plan is not quantified in CAT’s analysis of South Korea’s current policy projections, due to the lack of laws or measures to implement them. The CAT estimates that if fully implemented (and taking into account the expected lower level of electricity demand highlighted above), these announcements would lead to about 20% reduction in electricity-related emissions below the upper bound projections of the current policies scenario in 2030 (see our December 2019 update) and result in similar emission levels as the lower bound projections of the current policies scenario.

The Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS), which replaced a previous feed-in tariff scheme and has been in place since 2012, is the main policy instrument to promote renewable energy. The RPS scheme requires major electric utilities to increase their renewable and “new energy” share in the electricity mix to 10% by 2023 (Korea New and Renewable Energy Center, 2019). Our current policies scenario projections on renewable electricity is modest partly due to this unambitious RPS.

One of the main cross-sectoral policy instruments implemented to date is the Korea Emissions Trading Scheme launched in 2015 (ICAP, 2019b). The ETS cap for Phase II (2018–2020) was announced in July 2018 and is set to increase from 1,686 CO2e in Phase I (2015–2017) to 1,796 CO2e in Phase II.

In the transport sector, the number of annual electric vehicles (EVs) sales doubled from 2017 to 2018 to 33,000, accounting for over 2% of total new car sales in 2018 (IEA, 2019b). The South Korean Government is pushing the uptake of EVs through subsidies and tax rebates (IEA, 2019b), with the goal of having 430,000 EVs on the road by 2022. The government is also investing in a programme to improve charging infrastructure.

On 14 July 2020 President Moon Jae-In announced a “New Deal” to the tune of KRW 160 trillion (USD 130 billion; including private and local government spending) (Cheong Wa Dae, 2020). The announced New Deal contained a KRW 42.7 trillion (USD 35 billion) plan to boost renewable energy deployment and low-carbon infrastructure, including support to put 1.13 million electric vehicles and 200,000 hydrogen vehicles on the roads by 2025 (Shin and Cha, 2020).

However, the New Deal did not deliver what the ruling party promised during the general election campaign: no net zero emissions target by 2050, no carbon tax and no commitment to end financing coal power plants overseas. The South Korean government also did not commit to a phase-out timeline for internal combustion vehicles. If these climate targets were formally adopted, South Korea would become the first country in East Asia to commit to carbon neutrality by 2050. The comprehensive plan is still in discussion within the government, and it remains to be seen which policies will survive.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter