Policies & action

Switzerland’s efforts to tackle climate change are heading in the right direction again, since passing the new Federal Act on a Secure Electricity Supply with Renewable Energies in June 2024. Under current policies, Switzerland is projected to achieve even its not specified, estimated domestic target of a 30% to 33% reduction below 1990 levels.

The CAT rates Switzerland’s current policies as “Almost sufficient” when compared to modelled domestic pathways. The “Almost sufficient” rating indicates that Switzerland’s climate policies and action in 2030 are not yet consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C. If all countries were to follow Switzerland’s approach, warming could be held at – but not below – 2°C.

Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against modelled pathways and fair share) can be found here.

Policy overview

Switzerland’s emissions decreased from 45 MtCO2e in 2021 to 41 MtCO2e in 2022, 25% below 1990 levels. The decrease from 2021 to 2022 was mainly driven by a lower demand for gas and heating fuel in the building sector due to the warmer than average winter and subsequently lower need for space heating.

The new Federal Act on a Secure Electricity Supply with Renewable Energies (Bundesgesetz Über Eine Sichere Stromversorgung Mit Erneuerbaren Energien, 2024), approved in a June 2024 referendum, greatly impacts emissions projections under current policies, potentially leading to emissions levels as low as 28 MtCO2e (excluding LULUCF) by 2030. This projected reduction is equivalent to almost 50% reduction below 1990 levels (excluding LULUCF). Switzerland would therefore meet its estimated domestic target of a 30% to 33% reduction in emissions below 1990 levels under current policies and would get very close to meeting its overall NDC of a 50% reduction below 1990 levels through even without the use of carbon credits from international mechanisms.

CO2 Act

The CO2 Act is the key policy addressing emission reductions in Switzerland. To implement the Paris Agreement in Swiss legislation, an amendment of the CO2 Act (known as Total Revision) was drafted to make the 2030 NDC target legally binding (Schweizer Parlament, 2020). However, the Act was rejected in a public referendum in 2021, forcing Switzerland to extend its expired and unambitious CO2 Act to 2024 and start a process of drafting a new amendment.

A new amendment of the CO2 Act (known as CO2 Succession Act) was subsequently presented and accepted by parliament in March 2024. This version, however, includes substantially weaker provisions than the original, and all draft versions appear to have decreased in ambition in every round; i.e. there is no longer a clear domestic emissions reduction target, and all bans were removed from the original text.

Besides the 2030 target, the Act includes measures across various sectors including buildings, transport, industry, and aviation. It also covers climate adaptation support, support for companies exposed to the emissions trading system, and cleaner energy technologies like biogas and renewable fuels (Bundesgesetz Über Die Reduktion Der CO2-Emissionen (CO2-Gesetz), 2024). As this piece of legislation is still open for public consultation and amendments, and will only come into effect in 2025, it is not yet included in current policy calculations.

Climate Protection Act

On 18 June 2023, the Swiss people accepted another important piece of legislation in a public referendum, the Federal Act on Climate Protection Objectives, Innovation and Enhancement of Energy Security (the Climate Protection Act). It enshrines the net-zero emissions target for Switzerland by 2050 in law and sets interim and sectoral targets.

The Climate Protection Act also promotes innovation by providing support for companies to achieve their net zero target, addresses energy security through a programme that funds the replacement of fossil-fuel and electric resistance heating systems and covers adaptation support. The Act, however, is mainly a framework law, mandating the parliament to work out more concrete objectives and measures to meet the 2040 and 2050 sectoral targets. The Federal Act on a Secure Electricity Supply with Renewable Energies (see below) is set out to address this to some extent.

Carbon Levy (CO2 tax)

Switzerland introduced a carbon levy charged on fossil fuels in 2008, which covers ~35% of CO2 emissions. The fee was repeatedly raised over time, culminating at CHF 120 per tonne of CO2 (USD 130) in 2022, making it the highest CO2 levy in Europe (Swiss Broadcasting Corporation, 2021) (Alex Mengden, 2024). The CO2 Succession Act proposes to avoid many taxes altogether in favour of tax incentives and funding instruments in the transport, buildings, and industry sectors. The emphasis of Swiss climate policy is increasingly focussing on incentives rather than bans and restrictions, in order to avoid more rejection at the ballot, which means it includes some exemptions to the CO2 levy, including plant operators that commit to reducing emissions by 2040.

The majority of the proceeds from the levy are reimbursed to the citizens, or they flow into the (new) buildings programme and the economy. In 2023, the total revenue from the levy was around CHF 1.1 bn (USD 1.3 bn), of which roughly two thirds was redistributed to the population and the rest to the economy (Bundesamt für Umwelt BAFU, 2024a)

Emissions Trading Scheme

Another cross-sectoral instrument influencing greenhouse gas emissions is Switzerland’s emissions trading scheme (ETS). Companies participating in the ETS are excluded from an obligation to pay the emissions levy. After linking with the EU ETS in 2020, the price of Swiss emissions allowances broadly aligned with the higher EU allowance prices, which will accelerate emission reductions by the emitters responsible for a third of emissions resulting from the combustion of fossil fuels (EEX, 2019; Swiss Federal Audit Office, 2017). In November 2019, the Federal Council expanded the scope of the Swiss ETS to include civil aviation and fossil-thermal power plants (ICAP, 2020).

ECHR Ruling

In November 2020, a group of senior women in Switzerland filed a case against the Swiss government at the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), claiming that inadequate climate policies threaten their health and violate their rights to life and private life. The court ruled in April 2024 that Switzerland had failed to protect these rights from climate change impacts and lacked an effective regulatory framework to meet emission targets, marking an unprecedented application of human rights law in climate litigation.

Despite this landmark ruling, in June 2024, the Swiss parliament rejected the ECHR's decision, arguing that the country already has an effective climate strategy and the Swiss government subsequently also dismissed the court's findings in August 2024, asserting that its climate policies are adequate and have been bolstered by recent legislation. Environmental groups criticised this dismissal, arguing that Switzerland's plans do not sufficiently address the urgent need to limit global warming to 1.5°C. The CAT echoes these concerns, indicating that while some progress is being made, Switzerland still falls short of meeting the standards set by the ECHR ruling (Domhnall O’Sullivan, 2024; Imogen Foulkes, 2024; Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, 2024).

Power Sector

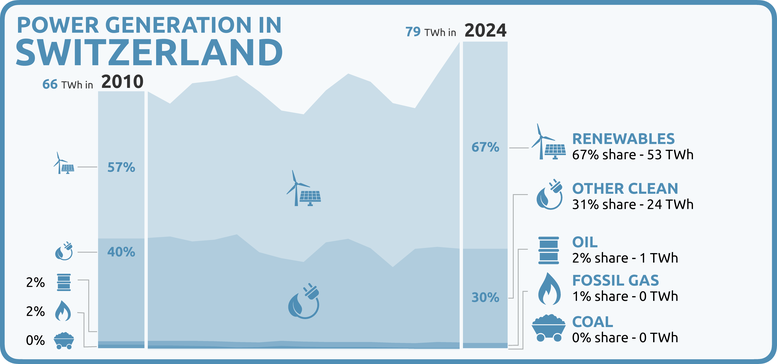

Switzerland’s power sector is largely decarbonised, ranking third globally in carbon intensity of electricity generation (41 gCO2) (Carbon Intensity of Electricity Generation, 1990 to 2023, 2024). In 2024, over 98% of electricity in Switzerland was generated from zero carbon sources, mainly from hydro (57%) and nuclear (31%) (Ember, 2025). The Swiss power sector has been included in the ETS since 1 January 2020, but this only affects a small number of operators given the sector’s highly decarbonised nature.

The Energy Strategy 2050 became the key framework in the energy sector when it replaced the previous Energy law. The energy strategy withstood a public referendum in 2017 and contains a package of measures aiming at increasing energy efficiency, reduction of CO2 emissions, and steadily replacing nuclear energy with renewables (Bundesamt für Energie, 2018a).

To execute the strategy, Switzerland revised its Energy Act (EnG) and set targets for the expansion of electricity production from renewable energy for 2020 and 2035. Switzerland exceeded the 2020 target for non-hydro renewables, but electricity generation from non-hydro renewables must increase by 450 GWh annually to meet the 2035 target of 11.4 TWh (Bundesamt für Energie, 2021).

While it is good that Switzerland has such targets, they should not be absolute but rather as a share of total, as this better reflects the increase in energy demand due to end-use electrification. The Act also prohibits the construction of new nuclear power plants and states that nuclear energy shall steadily be replaced by renewables.

The first of Switzerland's five nuclear power plants was shut down in December 2019. There is no schedule for the other four; they will likely continue running until at least 2030. In August 2024, however, the Environment Minister opened a discussion to amend the Act to again allow the construction of new nuclear plants. While this argument is based around “technology openness”, experts warn this is a derailing tactic to divert the conversation away from implementing the necessary wind and solar expansions (Sarah Schmalz, 2024).

The Act also includes a goal for decreasing per capita electricity consumption and introduced some changes to feed-in tariffs for renewables, including shortening the period during which new installations receive the tariffs from 20 to 15 years (Die Bundesversammlung der Schweizerischen Eidgenossenschaf, 2018; VSE, 2019).

For energy security reasons, Switzerland is highly dependent on traded electricity with its neighbouring countries. Since 2007, non-EU member Switzerland has been negotiating with the EU to form an agreement to better integrate its own market with the EU electricity market. When negotiations on institutional bilateral agreements between Switzerland and the EU were abruptly terminated in 2021 (based on non-energy/climate related issues), discussions on Switzerland’s access to the European electricity market were also put on hold. As a result, Swissgrid, the Swiss grid company, has had to negotiate technical, private-law agreements with European transmission system operators.

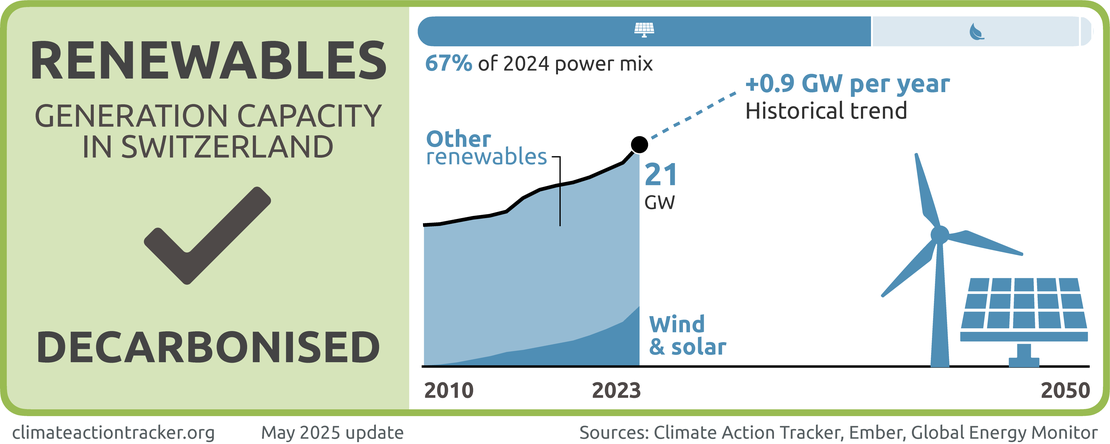

Renewables

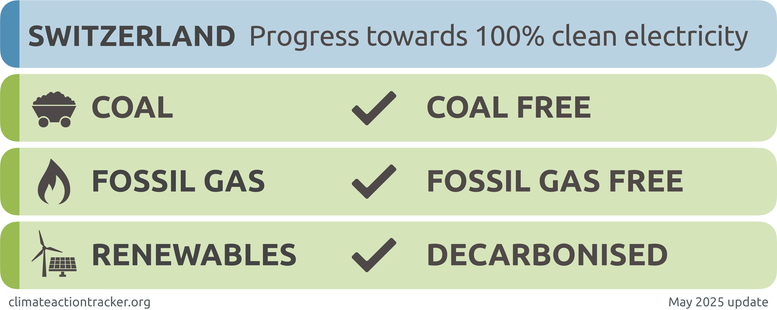

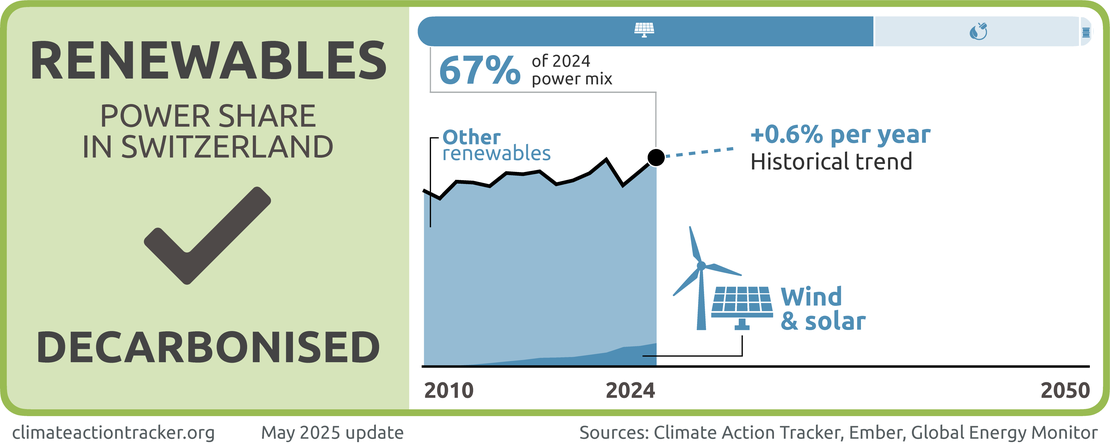

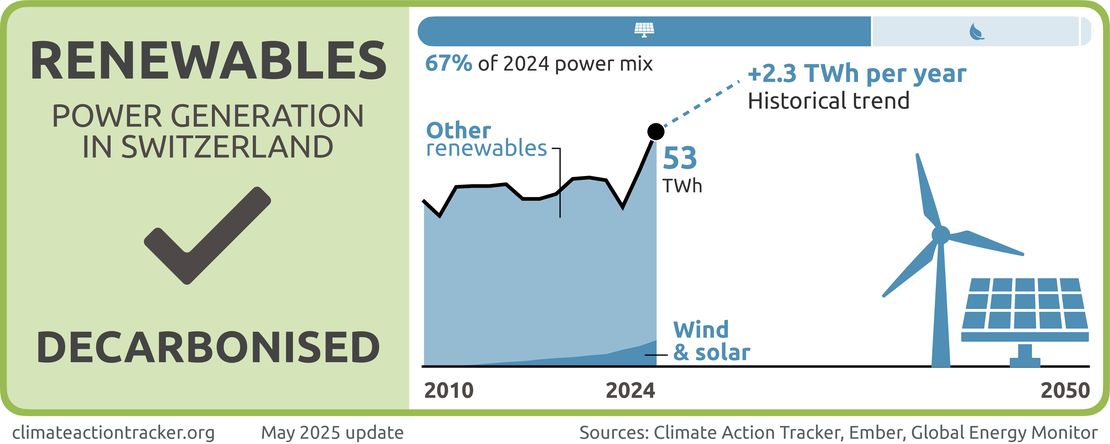

We evaluate the sector as “Decarbonised”. Renewables accounted for 67% of Switzerland’s electricity mix in 2024, with hydropower remaining the dominant source at 57%. Wind and solar have steadily increased in the last five year, rising from 3% in 2019 to 8% in 2024. In 2023, 1.5 GW of new wind and solar capacity were added to the grid (Ember, 2025).

The government is aiming to further support the expansion of wind and solar capacity. In June 2021, the Federal Act on a Secure Electricity Supply with Renewable Energies was launched to set out the necessary amendments to the Energy Act and the Electricity Supply Act to be aligned with the energy strategy 2050, and after several iterations it withstood a public referendum in June 2024 and now is enacted. It includes renewable installation targets for 2035 and 2050 of substantial scale: generation of non-hydro renewable generation needs to grow to 35 TWh in 2035 and 45 TWh in 2050 (from 6 TWh in 2023) while hydropower generation not go below 37.6 TWh in 2035 and 39.2 TWh in 2050.

The Act further includes demand targets to enforce improvements in energy efficiency and includes electricity import thresholds. It also includes specific market-oriented support mechanisms such as the introduction of competitive tenders and investment contributions, phase-out of feed-in tariffs and expansion of market premiums.

Another central part is the a mandatory construction of rooftop PV for new buildings, but this was weakened to only include buildings with a chargeable building area (roofs or facade) of over 300m2.(IEA, 2024; Bundesgesetz Über Eine Sichere Stromversorgung Mit Erneuerbaren Energien, 2024).

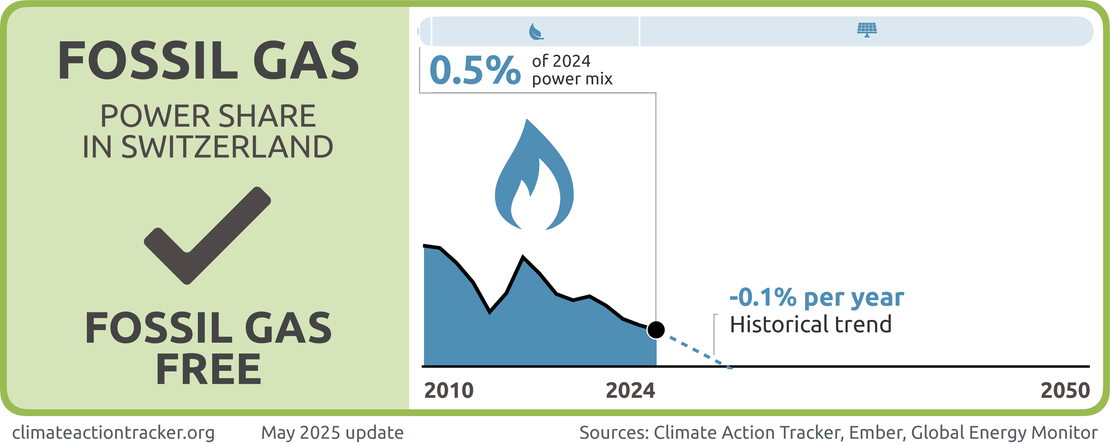

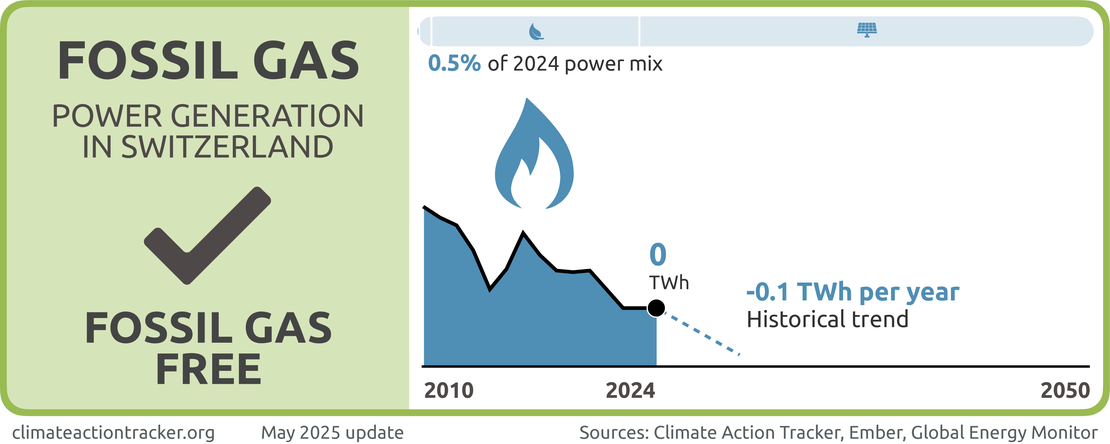

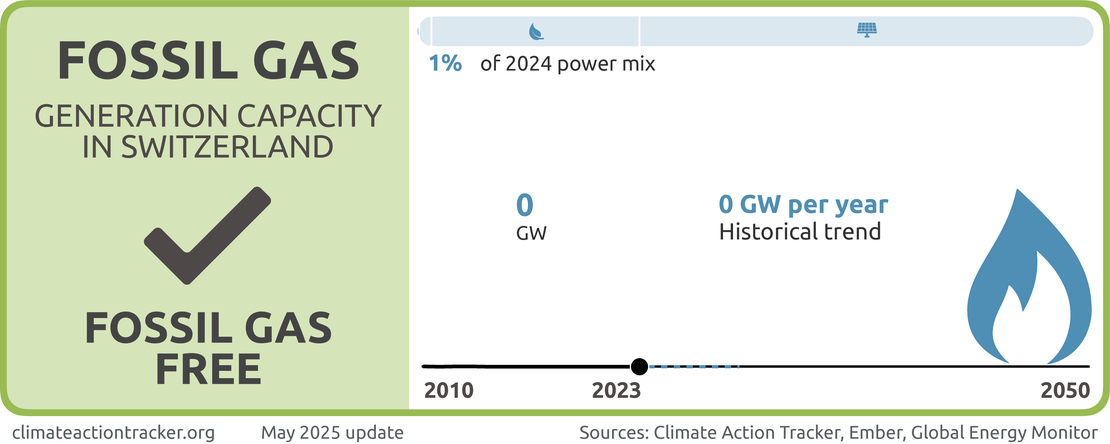

Fossil gas

We evaluate Switzerland’s power sector as “Fossil gas free”. The share of gas in the electricity mix has consistently been below 1% in the last five years and the government currently has no plans to build additional capacity (Ember, 2025).

Industry

Emissions from manufacturing industries, construction and industrial processes and product use (IPPU), accounted for 23% of Switzerland’s CO2 emissions in 2022. These levels are almost equal to those in 1990 (Bundesamt für Umwelt BAFU, 2024b). With Switzerland's new Climate Protection Act that passed a referendum in 2023, Switzerland now has emissions reductions targets for the industry sector to reduce emissions by 50% by 2040 and by 90% by 2050 below 1990 levels (Bundesgesetz Über Die Ziele Im Klimaschutz, Die Innovation Und Die Stärkung Der Energiesicherheit (KlG), 2023).

Most GHG emission reduction policies and measures affecting Switzerland’s industry sector are implemented under the CO2 Act and cover CO2 emissions from fossil fuel use. These include the CO2 levy on heating and process fuels, the Swiss ETS, and the negotiated reduction commitments. A number of key non-CO2 emissions are not covered under the Act, and have been targeted separately. For example, a number of provisions relating to substances stable in the atmosphere cover all F-gases and are expected to result in a reduction of roughly 1.1 MtCO2e in emissions of such gases in 2020 (Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, 2020c).

Similar to the EU, Switzerland also uses an ETS to lower emissions from large, energy-intensive entities. The Swiss ETS is much smaller than the European ETS, not only because of the smaller market but also due to the fact that the emissions generated by 54 companies in the power, cement, pharmaceutical, refinery, paper, district heating, and steel sectors covered by the scheme represent only 10% of the country’s emissions.

Emissions from the sector were capped in 2013 at 5.63 MtCO2, and required to reduce by 1.74% per year in order to reach a target of 4.91 MtCO2 in 2020 (13% reduction on 2013 levels) (Mission of Switzerland to the European Union, 2017). From 2021, the annual required rate of reduction rose to 2.2% of the 2010 baseline, which applies until 2030 (Federal Office of the Environment, 2020).

Transport

Emissions from the transport sector were responsible for 33% of Switzerland’s total GHG emissions in 2022, almost exclusively from road transport (Bundesamt für Umwelt BAFU, 2024b). Since peaking in 2008, transport emissions have steadily been decreasing and in 2020 they fell below 1990 levels for the first time since 1996, primarily due to lower car travel during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Emissions only slightly rebounded in 2021 and even slightly decreased again in 2022, remaining at 7% below 1990 levels. With the adoption of the Climate Protection Act in 2023, Switzerland now has reduction targets for the transport sector to reduce emissions by 57% by 2040 and by 100% by 2050 (below 1990 levels) (Bundesgesetz Über Die Ziele Im Klimaschutz, Die Innovation Und Die Stärkung Der Energiesicherheit (KlG), 2023).

Given the very low emissions intensity of Switzerland’s power sector, a shift to electric mobility has an even higher impact on overall emission reductions. In 2023, 30% of all new passenger cars sold in Switzerland were electrically chargeable vehicles, which includes battery-only (21%) and plug-in hybrid (9%) vehicles (European Alternative Fuels Observatory, 2024a). Although the uptake of electric vehicles is accelerating, the share of new sales in Switzerland remains significantly below that of some countries with a comparable level of income (e.g. 60% in Sweden, 55% in Finland, 90% in Norway in 2023), but it is moving faster than the EU27 average, which in 2023 was 23% (European Alternative Fuels Observatory, 2024b).

The target of 15% battery electric vehicle sales in 2022, outlined in the Roadmap for Electric Mobility 2022, was met a year early leading to the creation a new Roadmap for Electric Mobility 2025, with 2025 targets of EV market sales shares of 50% and of 20,000 charging stations. Although the EV uptake is expected to take an exponential trajectory to achieve 50%, sales need to more than double within two years (Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, 2023)(Bundesamt für Strassen ASTRA, 2023).

While still predominantly on road, the share of freight transported by rail – which is electrified to 99.8% in Switzerland – is slowly growing again and reached 38% in 2022. This is higher than even the EU target for 2030, which is 30% and the current EU average was 18% in 2021 (Bundesamt für Strassen BFS, 2023).

The inclusion of domestic and international aviation between Switzerland and member states of the European Economic Area (EEA) into Switzerland’s ETS since 1 January 2020 is a significant policy development, with emissions from the sector in the scheme to be capped at 2018 levels (Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, 2020c). In addition, from 2020 for new designs, and from 2023 for in-production models, aircraft in Switzerland will be subject to CO2 emission reduction targets. Switzerland also participates in the carbon offsetting and reduction scheme for international civil aviation (CORSIA), under which emissions are capped at 2019 levels. Despite becoming more stringent in 2024, this scheme has significant shortcomings, meaning it is unlikely to deliver the substantial reductions needed to achieve the ICAO’s aspirational goal of carbon neutral growth from 2020.

Within the framework of the new CO2 Succession Act, the introduction of a sustainable aviation fuel blending mandate is planned, in coordination with the EU’s ReFuel programme from 2025 and it also includes instruments to support the conversion of diesel-powered buses and ships to fossil free alternatives. The CO2 Succession Act further introduces quantitative emissions reduction targets for the period after 2025 aligned with those of the EU. It also introduces a new penalty for exceedance of emissions limits at CHF 95 to CHF 152 (USD 119 to USD 176) for each gram of CO2/km exceeding the individual target (Bundesgesetz Über Die Reduktion Der CO2-Emissionen (CO2-Gesetz), 2024).

Buildings

In 2022, the buildings sector, including commercial and residential, was responsible for roughly 23% of Switzerland’s total GHG emissions (excl. LULUCF), a decrease from 1990 levels when they represented around 30% of the country’s emissions. The warm winter of 2022 and subsequent lower demand for emissions intensive heating, contributed to this low number, which – in absolute terms – fell below 10 MtCO2e for the first time, a reduction equivalent to 44% below 1990 levels (Bundesamt für Umwelt BAFU, 2024b).

While missed in 2020, for the first time the achieved emission reduction in 2022 was larger than the goal of a 40% reduction in emissions below 1990 levels by 2020 that was adopted in the 2012 CO2 Regulation (Der Bundesrat, 2012). With the adoption of the Climate Protection Act, Switzerland now has targets for the buildings sector to reduce emissions by 82% by 2040 and by 100% by 2050 (below 1990 levels) (Bundesgesetz Über Die Ziele Im Klimaschutz, Die Innovation Und Die Stärkung Der Energiesicherheit (KlG), 2023).

Within this same Climate Protection Act, a programme to replace fossil-fuelled heating systems with renewable energy sources is prominently featured. The programme receives an annual budget of CHF 200 million (USD 230 million), partly cross-subsidised by the CO2 levy, for 10 years by the Federal Government. Subsidy details and minimum requirements will be defined by the Federal Council (Bundesgesetz Über Die Ziele Im Klimaschutz, Die Innovation Und Die Stärkung Der Energiesicherheit (KlG), 2023).

The focus on heating systems is important, as seen by the impacts that a warmer winter have on overall emissions, and previous efforts have already shown positive results. While 37% of homes were still heated by oil heating systems in 2023, this number has decreased from 59% in 1990.

Unfortunately, a substantial share of this reduction has been taken up by other fossil fuels, namely gas (17% in 2023, up from 9% in 1990). The share of buildings with gas heating, however, has dropped for the first time in 2023. Heat pumps are on the rise and already the main heating source in new buildings, accounting for 21% of homes in 2023 (up from only 4.1% in 2000 and 17% in 2021). In new buildings built between 2011 and 2023, 73% were equipped with heat pumps while fossil fuels like heating oil (just over 1%) and natural gas (10%) are in clear decline.

Besides these traditional energy carriers, district heating is also playing an increasingly important role, accounting for 7% of new buildings and accounting for a total of 3.8% of total buildings in 2023 (Bundesamt für Statistik BFS, 2024).

In Switzerland, regulations and bans on specific heating systems are usually made on the Cantonal level. The installation of new direct resistance heating – with few exceptions – is now banned in all cantons. In some Cantons, such as Zurich, a phase out for such heating systems is even planned for 2030 (buildigo, 2024). The Conference of Cantonal Energy Directors (EnDK), has proposed to the Cantons to ban installations of new oil and gas heating systems by 2030 (with few expectations) (Häne, 2023). The Canton of Zurich already has a law in place that bans the installation of fossil heaters to replace older heating systems (Kanton Zürich, 2024).

Switzerland has several energy efficiency labels for buildings, the so called “Minergie” standards. There are three major categories: Minergie houses should not consume more than 55 kWh/m2 for new single houses and 90 kWh/m2 for renovations. For Minergie-P the standards are 50 kWh/m2 and 80 kWh/m2 respectively. For Minergie-A the standards are 35 kWh/m2 and heating should be zero or below zero. By May 2023, there were over 55,000 Minergie-certified buildings in Switzerland (Minergie, 2022). These are only certifications and not mandatory standards. Public referenda at the local level to mandate that all new buildings have certain Minergie standards have so far failed to pass.

Agriculture

Emissions from the agriculture sector in 2022 constituted around 16% of total emissions (excluding LULUCF), representing a roughly constant share of total emissions as they have been decreasing at around the same pace as overall emissions (Bundesamt für Umwelt BAFU, 2024b).

In 2023, Switzerland released its new Climate Strategy for Agriculture 2050, replacing the 2011 Climate Strategy for Agriculture with a more ambitious, comprehensive approach based on recent sustainable development and agricultural policy framework serving as a guideline for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and adapting to climate change in the agricultural sector, with a focus on enhancing food security.

The strategy sets three primary goals: adapting agricultural production to local climate conditions with at least 50% self-sufficiency rates, reducing the per capita ecological footprint of diets by two-thirds from 2020 levels, and cutting agricultural greenhouse gas emissions by 40% compared to 1990 (this shows an increase in ambitious from a previous one third increase) (Bundesamt für Landwirtschaft BLW; et al., 2023). The strategy includes some measures to achieve these targets, but the plan to make the reduction target mandatory by including it in the third CO2 Act was dropped after the rejection of the act by the Swiss electorate.

Swiss agricultural policy reform faced a significant delay with the suspension of AP22+, the successor of the Agricultural Policy 2014-2017 and 2018-2021. Switzerland’s AP 14-17 and AP 18-21 contained the abolition of unspecific direct payments (livestock subsidies, general acreage payments), additional funds for environmentally friendly production systems, and for the efficient use of resources (e.g., increase in nutrient efficiency and ecological set-aside areas, reduction of ammonia emissions) (Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, 2020c).

In 2020 and 2021, Parliament halted further policy development until the Federal Council could submit a detailed report on the future direction of agricultural policy. This June 2022 report aimed to provide a long-term vision, addressing unresolved issues from previous policies and the need for more sustainable agricultural practices. Following this, work on AP30+ began, with the Federal Council scheduled to review and discuss proposals in 2026, with hopes of finally implementing a sustainable and cohesive agricultural policy framework (Der Bundesrat, 2022).

Switzerland’s unique direct democratic system, which allows citizens to propose constitutional amendments via initiatives, has not been effective in advancing agricultural policy reform. Despite efforts – such as the 2021 initiatives on clean drinking water and pesticide reduction, both rejected by 61% of voters, and the 2024 biodiversity initiative, rejected with 63% – all three proposals were blocked at the ballot, largely due to the strong influence of the farming lobby (Müller, 2021; Rigendinger, 2024)

Forestry

Except for a few selected years, forestry constitutes a sink of emissions in Switzerland of between 1–4 MtCO2 annually. In the current policy scenario this is expected to remain the case until at least 2035. However, this is expected to change with additional measures, as the sector would be projected to become a source of emissions by as soon as 2025 (1.1 MtCO2) and in 2030 to 2035 reaching roughly 1.7 MtCO2e of emissions per year (Bundesamt für Umwelt BAFU, 2024b). Roughly 31% of Switzerland’s total area is covered by forests, a value that has remained constant over the past years.

Waste

Emissions from the waste sector in Switzerland made up roughly 3% of total GHG emissions (excluding LULUCF) in 2022 and registered an absolute decrease of almost 50% since 1990 (Bundesamt für Umwelt BAFU, 2024b). Since 2000, the disposal of untreated municipal waste into landfill has been prohibited, with an increase in the capacity of waste incineration plants implemented to accommodate this ban (Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, 2020c). These incineration plants have substantially reduced methane emissions from Swiss landfills and produce roughly 2% of Switzerland’s total energy consumption.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter