Country summary

Overview

NDC update: In December 2020, the UK announced an updated NDC. Our analysis of its new target is here.

The onset of the COVID-19 crisis has had a severe impact on the UK economy, and the government’s commitment to “build back greener” has so far not been matched by strong action. To date only 2% of the economic recovery funds are allocated towards climate related measures, compared to 30% of the EU’s latest 2021-2027 budget and associated recovery package. Since legislating its 2050 net-zero emissions target in 2019, the UK has been strengthening its announced suite of climate policies, an encouraging development. However, according to a key advisory body, these announcements do not yet go far enough to put the UK on a path to achieve the 2050 net-zero target. With the UK set to host the pivotal UN COP26 climate negotiations in November 2021, there is great impetus to show global leadership by bridging this policy gap. The CAT rates the UK as “Insufficient”.

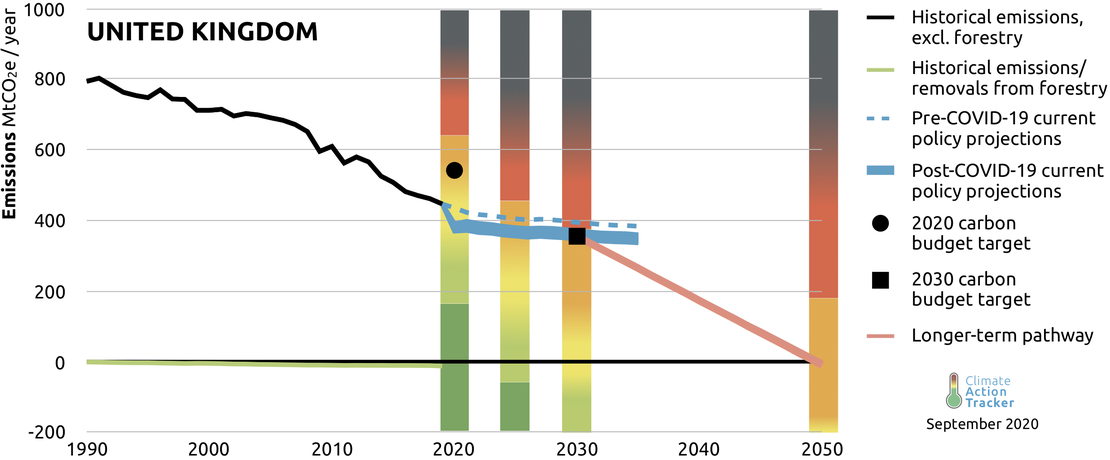

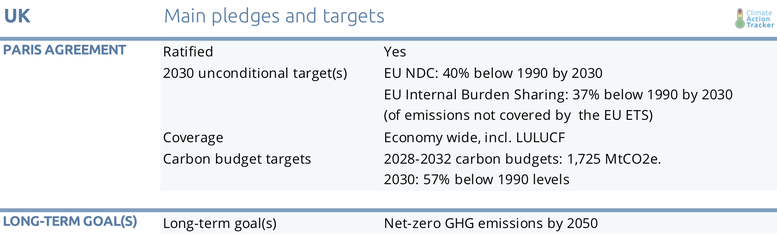

The economic slowdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic is expected to result in a 13-17% decline in UK greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2020 below 2019 levels. As a result, it is now possible the UK could achieve its 2030 climate target of a 57% reduction below 1990 levels under current policies. However, this target was set back in 2016, and is not compatible with achieving its 2050 net-zero target. Having left the EU in early 2020, the UK is no longer bound by the EU target and will need to submit its own, an ideal opportunity to formalise a stronger domestic target in line with its 2050 net-zero goal and a further chance to show global leadership ahead of COP26 next year.

In July 2020, as part of its COVID-19 economic recovery package, the UK government announced a £3 billion investment for improving the energy efficiency of homes and public buildings. This is far less than the £9.2 billion pledged for this purpose during the 2019 election campaign. Along with a £350 million investment in reducing emissions from heavy industry, these are the only significant climate-related investments in the recovery announced so far. The UK has stated it plans an additional round of spending later in the year, which will require a scaling up of commitments to fulfill the intent of its purported “green” recovery.

The release of key sectoral strategies later in 2020 will be critical in assessing the UK government’s commitment to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. Chief amongst them is the Transport Decarbonisation Plan, as transport emissions remain the largest single emissions source in the UK economy, and are currently only marginally below 1990 levels. The Energy White Paper, originally scheduled for release in mid-2019 will lay out the path forward to decarbonisation of the energy system, while the Heat and Buildings Strategy and Future Homes Standard, both currently under development, will be pivotal in ensuring a rapid decarbonisation of the buildings sector, a key challenge for the next decade and beyond.

A number of significant policy developments have been adopted over the last 12 months which will contribute to reducing the UK’s future emissions. These include a £2 billion investment to improve cycling and walking infrastructure, the reversal of a 2015 ban on onshore wind and solar PV projects from competing in renewable energy tenders, and the approval to proceed with a large-scale high-speed rail project despite major cost blowouts. Other measures announced but yet to be legislated include the bringing forward of a 2040 ban on fossil fuel vehicles to 2035, and a ban on the installation of gas boilers in new homes from 2025.

As a result of sustained political pressure from the activist group Extinction Rebellion, the UK government agreed to the formation of a ‘citizen’s assembly’ on climate change in 2019. This group of 110 citizens representative of the general population met over four weekends in early 2020 to learn about climate change and how the UK can address it, and to discuss what policies they would like to see implemented to reach the UK’s net-zero 2050 emissions target. The assembly’s final report is due in September 2020, which will be used by six select committees of the House of Commons as the basis for detailed work on implementing the assembly’s recommendations. An interim briefing found that 79% of assembly members strongly agreed, or agreed that the government’s economic recovery should be designed to help achieve the 2050 net-zero target.

Although the UK left the EU in early 2020, it has committed to continue working with the EU, aligning and, where possible, going beyond the EU’s climate and energy ambitions. The UK’s current targets are more ambitious than what was required under the EU effort-sharing legislation, so there is no expectation of a weakening of climate policy ambition as a result of leaving the EU.

The government’s current 2030 target of a 57% reduction in GHG emissions below 1990 levels is rated as ‘Insufficient’, for limiting warming to below 1.5°C.

The UK government’s strengthening of climate policies over the last 12 months is a welcome development, but as the CCC notes, there is still much more needed in order for the UK to be on a path to its target of net-zero emissions by 2050. In its 2020 progress report to Parliament, the CCC outlined that while 14 of its 21 key indicators of necessary progress are heading in the right direction, only four indicators were on track in 2019, and these were the same four as in 2018. They relate to total vehicle distance driven, emissions from, and renewable energy generation in the power sector, and the percentage of heat demand from buildings coming from low carbon sources.

In a separate correspondence to the Prime Minister, the CCC outlined six specific policy priorities that would support climate goals and the economic recovery from the COVID-19 crisis and could be delivered in the nearer term in the context of social distancing. These are: reskilling and training programmes, targeted science and innovation funding, housing retrofits and building homes that are fit for the future, strengthening energy system networks, tree planting, peatland restoration and green infrastructure, and making it easy for people to walk, cycle and work remotely.

The UK’s primary policy success in addressing climate change so far has been achieved in the electricity sector, with emissions from this sector more than halving between 2014 and 2019. This has primarily been achieved by shutting down coal-fired power stations and investing heavily in renewable energy technologies. However, with limited coal now left in the electricity system, further emission reductions in the coming decade will also need additional action in other sectors.

The progress so far in transitioning to renewable energy has been encouraging, with the electricity output of renewables in Q3 2019 outpacing the output of all fossil fuels combined for the first time ever. Electricity generation from renewables reached a record high 36.9% in 2019, while current policy projections show a further scaling up of renewable energy to approximately 52% of generation by 2030.

The future of offshore wind looks particularly bright, with the government’s 2019 renewable energy auction yielding six new offshore wind farms totalling 5.5GW. The electricity prices confirmed for these projects is below the government’s projected electricity price in 2024/25 and could generate cheaper electricity than existing gas-fired power stations by 2023. The previous target of 30GW of offshore capacity by 2030 has now been raised to 40GW.

In June 2020, the UK Government published its response to its consultation on the design of a future Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). It proposes a starting date of 2021, with the first phase running until 2030, but does not specify whether it will be linked to the EU ETS or be a standalone system, noting that the government is still considering both options. The scheme will cover energy intensive industries, the power generation sector, and aviation, including domestic routes, and those across the European Economic Area (EEA). This broadly aligns the proposed UK ETS with the current scope of the EU ETS, which also covers industry, the power sector, and aviation across the EEA.

The continued fall in pricing of renewable energy sources underlines outstanding questions as to the future viability of the UK’s nuclear sector, with three planned projects cancelled in late 2018 and early 2019. The projected price of power from future nuclear power plants remains high and the Hinkley Point C plant currently under construction continues to register cost blowouts and delays, with the total cost of the project now expected to be over £22 billion. A government retreat from nuclear power would require additional investment in renewable energy, and there is considerable anticipation for the government’s upcoming energy white paper scheduled for release later in 2020.

A 2035 ban on the sale of fossil-fuel vehicles, brought forward by the government from 2040 earlier this year, puts the UK in a small group of countries with such a policy, however the CCC has warned that this date needs to be brought further forward, to no later than 2032. The slow projected rate of future emission reductions from the transport sector also suggests the government must do more over the short term. The government decision to cut subsidies for electric vehicles twice in three years will make such short-term emission reductions more difficult to achieve.

The considerable progress made since 1990 in decarbonising the UK’s industry sector must continue if the UK is to meet its current emission reduction targets. The release in 2017 of eight sector-specific action plans for decarbonising UK industry by 2050 provides a blueprint for doing so. In 2030, industry emissions are projected to be 56% lower than 1990 levels, just under the economy-wide target.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter