Policies & action

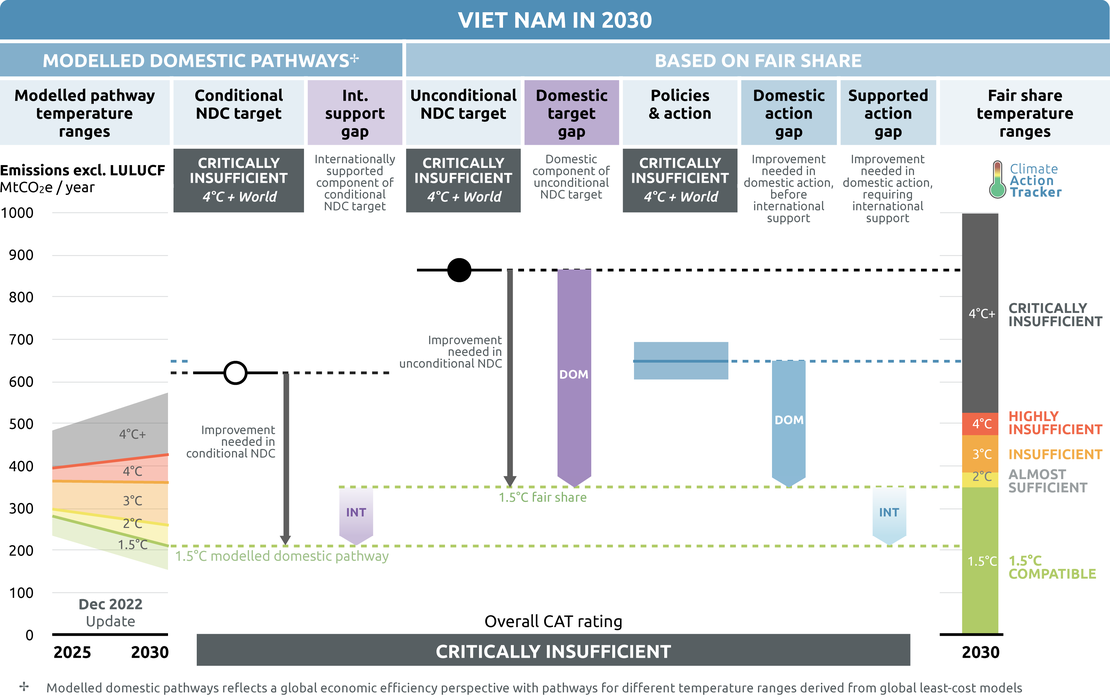

Viet Nam’s current policies and action are rated “Critically insufficient” when compared to its fair share contribution. Current policies will reach around 603-692 MtCO2e in 2030 (excl. LULUCF) whereas a 1.5˚C fair share pathway is 350 MtCO2e in 2030, indicating further domestic policies and international support are required for Viet Nam to align with 1.5˚C. Viet Nam’s conditional target falls within its current policy emission range, while its unconditional target will be easily met and is well above this level. Viet Nam’s emissions in 2030 under current policies and action will be around 118-150% above 2010 levels excluding LULUCF.

The “Critically insufficient” rating indicates that Viet Nam’s policies and action in 2030 reflect minimal to no action and are not at all consistent with the 1.5°C temperature limit. If all countries were to follow Viet Nam’s approach, warming would exceed 4°C.

Policy overview

National Climate Change Strategy to 2050

In July 2022, the Viet Nam government passed its National Climate Change Strategy to 2050 into law, representing an important step towards the country achieving its net zero emissions commitment by 2050. According to the strategy, by 2030, total GHG emissions will decrease by 43.5% compared to the business-as-usual scenario, in which there will be a 32.6% reduction in the energy sector, with the emissions amount not exceeding 457 MtCO2e by 2030 and 185 MtCO2e by 2050. This strategy has also set an emissions reduction target for other sectors: 38.3% from industrial process, 43% from agriculture and 60.7% from waste sector by 2030 from BAU level of emissions.

The strategy also calls for a gradual transition from coal-fired power to cleaner energy sources, reducing share of fossil fuel energy sources, not developing new coal-fired power projects after 2030, and gradually reducing coal power capacity after 2035. This is important for Viet Nam as a signatory of coal exit pledge in COP26.

Improving energy efficiency is also emphasised in this strategy by increasing the share of energy efficient equipment in industry, residential sector along with electrification of agricultural machinery and use energy efficient equipment in post-harvest agricultural production chain.

Law on Environmental Protection

A new Law on Environmental Protection came into effect on 1 January 2022 (replacing an older law from 2014) (Vietnam Briefing, 2022a). The law introduces a domestic carbon market with an emissions trading scheme, where businesses will have an emissions quota that can be traded. The law also allows for a carbon tax. The effectiveness of the carbon market depends on the carbon price, and the cap on emissions. A high cap on emissions would undermine the effectiveness of a carbon price; monitoring and enforcement would be critical (Do & Burke, 2021). The Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MORE) is developing a decree related to carbon pricing (Thi Khanh et al., 2021).

Draft Eighth Power Development Plan

The draft Eighth Power Development Plan (PDP8) is still pending approval from Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh and Deputy PM Led Han Thanh, who cite concerns about the high ratio of renewables in the energy mix given the challenges of grid distribution among Viet Nam’s geology (RECOURSE, 2022).

The latest version of the draft (August 2022) scales down coal (from 46% in 2021 to 9.5% in 2045), increases renewable energy, but ramps up gas. Viet Nam’s latest draft proposes a 50.7% share of wind and solar power in 2045, compared to 40% in previous versions (Energy Tracker Asia, 2022b). To achieve this share Vietnam will need 42.7 GW of onshore wind, 54 GW of offshore wind and 54.8 GW of solar power by 2045 (Energy Tracker Asia, 2022b).

The plan also aims to limit the country’s reliance on fossil fuels and avoid adding any new coal-fired power plants. But it also proposes a large portion of installed fossil gas capacity over 24 GW by 2030, including seven additional LNG import terminals and 22 LNG-to-power projects, operationalising an additional 34 GW by 2045 (Morris, 2022). The draft PDP8 remains focused on fossil fuel for baseload power, and it is at odds with global and regional decarbonisation trends. The latest version of PDP8 also focuses on alternative forms of energy such ammonia and hydrogen.

National Energy Development Strategy

In February 2020, the Politburo issued Resolution No. 55 on the orientation of the National Energy Development Strategy of Viet Nam to 2030, with a vision to 2045 (Viet Nam Government, 2020b). Resolution 55 is not represented in the CAT policies and actions pathway as it is yet to be implemented in a power development plan. The Resolution sets several targets for primary energy levels, total capacity of electricity generation, the total primary energy share of renewables, total final energy consumption, primary energy intensity, energy efficiency in the total final energy consumption and GHG emissions for the energy sector compared to business-as-usual (BAU). The Resolution supports the uptake of renewables, yet it also continues the development of coal, and also building the capacity for scaling up gas imports (see the energy section for further details).

Resolution 55 sets a target to reduce greenhouse gases emissions from energy activities by 15% by 2030 and 20% by 2045 from (an unspecified) BAU. The NDC aims for an unconditional 7% reduction in energy-related emissions below BAU by 2030 and an additional 18% based on international support. The NDC total reduction would lead to 24%, or 451 MtCO2e by 2030, whereas the current policies and action pathway is estimated to be around 447 MtCO2e by 2030 from the energy related emissions. Meeting these targets requires no action.

Viet Nam is highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change at 1°C above pre-industrial levels. With further temperature increases, climate-associated risks also increase, such as extreme heat, droughts, flooding, and sea-level rise impacting coastal areas and some agricultural production areas such as the Mekong delta (Climate Analytics, 2019a). Viet Nam is also a member of the Climate Vulnerable Forum which supports the full decarbonisation of member economies (Climate Vulnerable Forum, 2015).

In February 2021, Resolution of the XIII National Congress of the Communist Party stated Viet Nam needs to be committed to climate change adaptation, and mitigating natural disasters (Thi Khanh et al., 2021).

Just Energy Transition

Viet Nam’s net zero target and joining alliance to phase out coal from power generation are an opportunity to re-orient the nation’s economy along a just, sustainable, high-productivity trajectory. Given that a large part of population depends on coal for livelihood it is crucial for Viet Nam to understand the socio-economic impacts of coal phase out and the need for strategising around policies for an inclusive and sustainable transition.

In December 2022, Viet Nam joined the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP), under which it will receive USD 15.5 bn from a group of donor countries. Key elements of the agreement include the peaking of power sector emissions in Viet Nam at 170 MtCO2 in 2030 and a share of 45% of renewable energy generation by then (European Commission, 2022b). These targets enhance previous plans and, according to our preliminary assessment, exceed the level of ambition of our current policies scenario. The agreement also includes a biennial revision of the targets to increase their ambition. This a positive signal and mirrors the dynamic development of renewable energy in Viet Nam in the last years.

Sectoral pledges

In Glasgow, a number of sectoral initiatives were launched to accelerate climate action. At most, these initiatives may close the 2030 emissions gap by around 9% - or 2.2 GtCO2e, though assessing what is new and what is already covered by existing NDC targets is challenging.

For methane, signatories agreed to cut emissions in all sectors by 30% globally over the next decade. The coal exit initiative seeks to transition away from unabated coal power by the 2030s or 2040s and to cease building new coal plants. Signatories of the 100% EVs declaration agreed that 100% of new car and van sales in 2040 should be electric vehicles, 2035 for leading markets. On forests, leaders agreed “to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030”. The Beyond Oil & Gas Alliance (BOGA) seeks to facilitate a managed phase out of oil and gas production.

NDCs should be updated to include these sectoral initiatives, if they're not already covered by existing NDC targets. As with all targets, implementation of the necessary policies and measures is critical to ensuring that these sectoral objectives are actually achieved.

| VIET NAM | Signed? | Included in NDC? | Taking action to achieve? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methane | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Coal Exit | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Electric vehicles | No | N/A | N/A |

| Forestry | No | Yes | Yes |

| Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance | No | No | N/A |

- Methane pledge: Viet Nam is one of the signatories of Global Methane Pledge and committed to reduce methane emissions by 30% by 2030 compared to the base year of 2020. Around 21% of Viet Nam’s emissions are from methane. Absolute methane emissions have been declining since 2011. Methane emissions mainly come from the agriculture sector. Viet Nam has planned to adopt advanced solutions in agriculture production to reduce methane emission from cultivation and husbandry. In August 2022, Viet Nam released its national methane emission reduction plan with sector-specific goals for 2025 and 2030.

- Coal exit: During COP26, Viet Nam pledged to phase out unabated coal-fired power generation and stop construction of new plants. Viet Nam’s coal capacity grew by around 57% between 2014 and 2021. The Vietnamese government has adopted a plan to not develop new coal-fired power plants after 2030 and will gradually reduce its coal fleet after 2035. However, Viet Nam has a further 15.6 GW coal capacity in the pipeline – 7.4 GW under construction and 8.3 GW at pre-construction level. Viet Nam is exploring options to accelerate its phase-out of unabated coal power through the Just Energy Transition Partnership platform.

- 100% EVs: On 22 July 2022 Viet Nam adopted a green energy transition roadmap, the overall objective of this strategy is to develop a green transport system which will 100% operate through electricity or green energy by 2050 in consistent with its net zero target. At present the electric vehicle market in Viet Nam is very modest, with only 900 electric vehicles at the end of 2020, mainly hybrid models. However, with more than 87% of household owning a motorcycle there is high potential of electric two wheeler market in Viet Nam and electric two wheeler sales is also growing fast.

- Forestry: In 2016, Viet Nam’s sink capacity was 39 MtCO2e/year. In its National Climate Change Strategy to 2050, Viet Nam set a target to maintain forest coverage at 43% and ensure area of national forest; improve forest quality and sustainable forest management.

- Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance: This alliance was created with the aim to restrict any kind of fossil fuel expansion by ending licensing of new projects and phasing out existing oil and gas projects. Viet Nam has not joined this alliance.

Viet Nam is planning for rapid growth in fossil gas and LNG imports for gas-fired power generation. According to Viet Nam’s draft PDP8, 15 GW gas capacity through 22 new LNG-to-power projects are to be constructed by 2030, serviced by seven LNG terminals. Vietnam's domestic crude oil production and sales are also picking up rapidly after post-COVID recovery.

Energy supply

Share of energy sector emissions is 77% in Viet Nam’s total emissions in 2021 (Gütschow et al., 2022). In the updated NDC, more than half of the emissions reduction will come from this sector (Vietnam Government, 2022c). Viet Nam has experienced several challenges in its energy sector in recent years. Total final energy consumption has grown 147% from 2010 to 2019 (IEA, 2021). Viet Nam achieved universal electrification in 2015 and, with an increasing population and economic growth, it is not surprising there is mounting pressure for a secure energy supply (World Bank, 2019). The energy sector represented 68% of emissions in 2019 (Gütschow et al., 2021).

The main policy reflected in the current policy scenario is the revised Power Development Plan 7 (PDP7) discussed below under each fuel category (Viet Nam Government, 2016). The PDP 7 will be replaced by the PDP8. There have been several drafts of the PDP8 circulated, the latest draft used for this analysis is the August 2022 draft.

Coal

Viet Nam is a signatory of the global pledge to phase out unabated coal-fired power generation and stop construction of new plants (UN Climate Change Conference (COP26), 2021). Viet Nam government has adopted a plan to not develop new coal-fired power plants after 2030 and will gradually reduce its coal fleet after 2035. Viet Nam is now receiving international support from International Partners Group (IPG) through Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) platform to accelerate its coal phase-out plan and to achieve net zero by 2050.

Planned coal capacity is under revision in government plans, but the pipeline remains substantial. Coal represents 49.7% of the total primary energy supply and 46.6% of electricity generation in 2021 (BP, 2022a). Viet Nam’s latest draft Power Development Plan 8 (PDP8) plans to reduce current coal capacity to 9.5% by 2045 (Energy Tracker Asia, 2022b). A coal-based power plan places Viet Nam at risk of losing opportunities for cost competitive renewable energy projects as global financial flows move away from coal (Vu, 2021b). In contrast, Viet Nam has the fourth largest coal pipeline in the World after China, India and Indonesia at 15.6 GW - 7.4 GW under construction and 8.3 GW pre-construction (Global Energy Monitor, 2022b).

Viet Nam is cancelling an increasing number of coal projects, mainly due to a lack of financial viability (Veolia Planet, 2021). Between 2010 and 2022, Viet Nam has shelved 45 GW of coal capacity, one of the highest compared to the countries in terms of cancelling of coal projects, and one fifth of that cancellation took place between 2021-2022 (Global Energy Monitor, 2021, 2022b).

Despite the cancellations, Viet Nam’s coal pipeline is still extensive and needs to be revised to avoid the risk of stranded assets, particularly given the need to phase out coal globally and in non-OECD Asia as a region by 2040 (Climate Analytics, 2019c, 2019b).

Resolution 55 includes a guiding orientation towards scaling down coal-fired power generation, however, it also stipulates the development of a strategy for long-term coal imports, extending exploration activities, and increasing domestic coal extraction (Viet Nam Government, 2020b). The Resolution requires technology upgrades to existing coal plants to meet environmental standards, and develop capacity prioritising high efficiency units (Viet Nam Government, 2020b).

The Viet Nam Business Forum has produced a business case for investment in clean energy, finding that coal powered generation creates financial, security, environmental and public health risks (Vietnam Business Forum, 2019). Six provinces out of 63 have called for coal power projects (totalling 17.39 GW) to be cancelled due to environmental concerns (MDI, 2020).

Oil and gas

Oil represents 21.7% of the total primary energy supply, and natural gas has declined slightly in recent years, representing 6% in 2021 (BP, 2022a). In electricity generation, natural gas represents 10.7% and oil 0.5% in 2021 (BP, 2022a). Viet Nam is planning for rapid growth in fossil gas and LNG imports for gas-fired power generation.

According to Viet Nam’s PDP8, 15 GW via 22 new LNG-to-power projects are to be constructed by 2030, serviced by seven LNG terminals (RECOURSE, 2022). This increases the anticipated installed natural gas electricity generation capacity plan from 19 GW in 2030 (PDP7), to over 27 GW in the PDP8 (Baker McKenzie, 2021).

Resolution 55 aims to build capacity to import eight billion LNGm3 by 2030 and 15 billion LNGm3 by 2045 (Viet Nam Government, 2020b).

Renewable energy

Renewable energy projects have continued despite the global supply chain disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, electricity generation from biofuels represents 1%, solar PV 10% and wind <1% (BP, 2022a). The potential for renewables is reiterated in the recent World Bank Systematic Country Diagnostic Update for Viet Nam (2021), pointing out that Viet Nam has one of the fastest growing solar markets in the world, with more solar power capacity added in 2020 than in all of the ASEAN countries combined.

As of 2021, Vietnam has 16.5 GW of solar power and 11.8 GW of wind power capacity. A further 6.6 GW of wind capacity expected be installed by the end of 2022 (Energy Tracker Asia, 2022a). Ambitiously, the government is further planning of adding 12 GW of onshore and offshore wind by 2025. Share of renewable in power generation excluding hydro stands at 11.5% in comparison to less than 1% in 2015 (BP, 2022a).

According to the National Climate Change Strategy government is further planning to scale up the renewable energy as combined renewable energy capacity including hydro, wind, solar, and biomass are planned to reach at least 33% of electricity share by 2030 and 55% by 2050 (Vietnam Government, 2022b).

Hydro

Hydro power is the largest source of renewable energy in Viet Nam, representing 16% of the primary energy supply and 31% of the electricity generation mix in 2021 (BP, 2022b). The potential for large and medium scale hydro power has geographical limitations.

According to National Climate Change Strategy to 2050 Viet Nam will continue to develop small hydro plants selectively that meet environmental protection standards, expand medium and large hydroelectricity to maximise the effectiveness of hydro power.

Solar

The revised PDP7 set a target for 850 MW of solar PV in 2020, 4 GW by 2025 and 12 GW by 2030. By June 2019, Viet Nam had overachieved the 2025 solar target by 4.5 GW of solar (and wind represented 0.45 GW) (MOIT & DEA, 2019). The August 2022 draft of the PDP8 scales up these plans with 54.8 GW by 2045 in the baseload scenario (Energy Tracker Asia, 2022b). At present in Viet Nam more than 2.2 GW of solar capacity is under construction and another 12 GW is under various stages of development (Enerdata, 2022).

The solar support mechanism that led to the upscale of solar power in Viet Nam expired in June 2019. The lack of a support mechanism created a 10 month period of policy uncertainty (Publicover, 2020). The government extended the solar feed in tariff with Decision 13/2020 which applies to utility scale, rooftop and floating solar (Publicover, 2020; Vu, 2021a). Commercial projects will only receive the new rates if they are in operation by the end of December 2020, whereas new projects beyond December can enter into a competitive bidding process (auction) to determine the price (Publicover, 2020). The move from feed-in-tariff to auctions was pushed forward with two pilot auctions for floating solar (Bellini, 2020).

Viet Nam is leading the ASEAN region with floating solar plans, with 47 MW installed and 330 MW planned, whereas other ASEAN countries have less than 150 MW planned, and in 2019 most ASEAN countries had less than 1 MW of floating solar (Ahmed & Hamdi, 2020). Recently Viet Nam has announced two floating solar plants totalling 450 MW capacity with total investment of VND 7800bn (USD 340m) (Enerdata, 2022). Hydroelectricity is one of the main sources of renewable energy in the country, but prolonged dry seasons are reducing reservoir levels in dams and limiting how much electricity they can produce. These reservoirs are being utilised for floating solar projects with private sector financing (Government of Canada, 2021).

Other renewables

Feed-in-tariff mechanisms targeted to wind sources brought about new planned investment in wind power. Viet Nam has one of Southeast Asia’s largest offshore wind potentials. Around 10 GW (by 2030) of wind project plans have been submitted, with 5 GW approved for additional planning so far (MOIT & DEA, 2019).

It is estimated that Viet Nam has a potential for 16 GW of offshore wind within 5 to 100 km from the shore (Danish Energy Agency, 2020). In June 2020, the Prime Minister asked the Ministry of Industry and Trade to add more wind projects to the electricity development plan and extend the wind feed-in tariff deadline which currently applies to plants with operation dates before November 2021 (Massmann, 2020). The draft PDP8 proposes 50% renewable share in 2045, which requires 42.7 GW of onshore wind, 54 GW of offshore wind capacity (Energy Tracker Asia, 2022b)

Policy developments

Resolution 55 supports policies to promote clean energy, such as increasing the share of wind and solar in the total primary energy supply, encouraging investment in waste-to-energy plants; development of renewable energy centres; supporting studies for geothermal, wave, tidal, ocean current energy; and supporting pilot projects for hydrogen (Viet Nam Government, 2020b). Resolution 55 includes a new renewable energy target for renewables to represent 15-20% in 2030 and 25-30% in 2045 in the total primary energy supply (TPES) (Viet Nam Government, 2020b).

The revised PDP7 set targets for electricity capacity and electricity production. Plans for renewable energy encompassing small hydro, wind, solar and biomass, to represent 6.5% of electricity produced or imported in 2020, 6.9% in 2025 and 10.7% by 2030 (Viet Nam Government 2017a). Additional large, medium and pumped hydro is projected to represent 12.4% of electricity production by 2030 (Viet Nam Government 2017a). In terms of electricity capacity, 30.1% will be large/medium hydro and 9.9% other renewables in 2020; 17.4% large/medium hydro and 6.9% other renewables by 2025; and 16.9% large/medium hydro, and 21% other renewables by 2030. Official decisions by the Prime Minster encourage the uptake of wind and solar energy in efforts to encourage and assist the development of projects (MNRE, 2019).

Viet Nam has a Development Strategy on Renewable Energy, with plans to 2030 and a vision to 2050 (MNRE, 2019). The renewable energy targets in this strategy are reflected in the Revised PDP7 (included in the CAT current policy scenario) (MNRE, 2019).

The October 2021 draft of the PDP 8 shows rapid growth of solar and wind comprising 23% of the system capacity in 2030 and 50% in 2045, overtaking coal (Baker McKenzie, 2021). Solar and wind have large potential in the central and south of the country, and a transmission link to north Viet Nam is planned from 2025 (Brown & Vu, 2020).

Energy Efficiency

One strategy to cope with the rising energy demand is to improve energy efficiency. The Viet Nam National Energy Efficiency Program 3 (VNEEP3) (2019-2030) has a legislated target of reducing the total final energy consumption by 5-7% in 2025 below business as usual levels, and by 8-10% in 2030 (MOIT, 2019). The program also includes targets to reduce electricity losses, and industrial sub sector energy saving targets (MOIT, 2019).

Further incentives, such as via the Viet Nam Scaling Up Energy Efficiency Project (VSUEE) funded by the World Bank and GCF, provide de-risking and funding opportunities for companies engaged in energy efficiency certified projects. Aiming to mobilise approximately USD 250m, the projected energy or fuel savings anticipated for the 2019-2025 period are significant, up to 577 GW (Vietnam Briefing, 2022b; World Bank, 2020).

CAT current policy projections which is based on Reference scenario of APEC 2022 takes into account the energy savings from VNEEP3 but do not include VSUEE which would further reduce energy demand (APEC, 2022).

Transmission network and energy storage

Viet Nam’s boom in solar energy has led to pressure on the power grid (Allens, 2020). The state-owned company Viet Nam Electricity (EVN) has curtailed renewables without compensation, creating risks for investors and impacting the bankability of renewable energy projects (Allens, 2020; MDI, 2020). Viet Nam’s transmission grid faces limitations because larger energy projects are installed far from main demand centres. Reportedly, 0.44 GW of over 4.5 GW of new wind and solar experienced forced curtailment between 30 June 2019 and January 2020 (MDI, 2020). These limitations will likely delay the onset of new solar projects in the near future (MOIT & DEA, 2019).

Despite high growth in solar capacity, Viet Nam is currently unable to fully integrate this due to lack of storage capacity. To fully utilise its growing capacity of variable renewables and reduce curtailments, Viet Nam needs to support the growth of its energy storage infrastructure (MOIT & DEA, 2019) through regulatory mechanisms and sustained investments (Vietnam Investment Review, 2022). A grant for USD 2.96m has been awarded by the US government in Ho Chi Minh City, towards the construction of the pilot project of retrofitting battery storage in a utility sale solar power plant (Energy Storage News, 2021).

Co-benefits of renewables

The MOIT & DEA (2019) find that wind and solar will be cheaper than coal by 2030, with further cost reductions by 2050. Whereas a study by McKinsey and Company finds that Viet Nam is already at the tipping point where renewables are the lowest cost option to meet increased electricity demand compared to thermal power (Breu et al., 2019).

The potential for renewables is evidenced by a McKinsey and Company study, modelling a renewables-led pathway with five times more wind and solar than in the “Current Plan” (current policy pathway) (Breu et al., 2019).

The renewables-led scenario offers a “cheaper, cleaner, more secure” pathway compared to the current plan for Viet Nam’s energy sector (Breu et al., 2019). It is 10% cheaper (total cost from 2017 to 2030). The renewables-led pathway has less reliance on imported fuels improving energy security, reducing coal imports by 70%, and creates 465,000 additional jobs (from 2017 to 2030) (Breu et al., 2019). In addition, the renewables pathway is projected to reduce emissions by 1.1 Gt CO2e over the 2017-2030 period compared to the current plan (Breu et al., 2019).

Another report estimates the revised PDP7 would create 315,000 jobs annually to 2030 (GreenID et al., 2019). Renewables produce double the jobs per average installed MW compared to the fossil fuel sector (GreenID et al., 2019). This evidence suggests the government should prioritise renewables over fossil fuels in the PDP8.

There are many co-benefits between transitioning to renewable energy and sustainable development in Viet Nam, such as reducing fuel import dependency, improving the reliability of electricity supply, improving access to modern energy, reducing air pollution impacts both indoor (from switching from traditional biomass cooking) and outdoor (Climate Analytics, 2019a). This is also becoming important in the context of Viet Nam’s recent gas capacity expansion as that is mostly depends on imported LNG (Kumagai, 2021).

The implementation of an early retirement of the existing power plants and shrinking of the existing pipeline would also have spill over effects beyond mitigation, as coal-fired power generation significantly contributes to poor air quality and thereby causes serious health impacts. Viet Nam could avoid up to 81,000 premature death within its own borders between 2020 and 2050 by retiring its existing coal plants and reducing pipeline. This could save over 420,000 premature deaths if including the impact on affected neighbouring countries (AIRPOLIM, 2022).

These estimates are based on Global Energy Monitor 2021 data which reports 9.9 GW additional pipeline compared to 2022 (Global Energy Monitor, 2021, 2022a). Viet Nam can greatly reduce the health impacts of its energy system by planning an accelerated phase out of coal-fired power generation.

Industry

Industrial process emissions are mainly from cement production, but also steel and ammonia production (MNRE, 2019). This sector is projected to be the second largest sector in terms of emissions by 2030 based on the current policy pathway. Viet Nam’s first NDC excluded industrial processes emissions, but its 2020 and 2022 NDC updates have included industry emissions.

In 2015, the Minister of Industry and Trade approved the Green Growth Action Plan 2015-2020 for the industry sector, and the Ministry of Construction has an action plan until 2020 to reduce cement industry GHG emissions (MNRE, 2019). The plan aims to reduce 20 MtCO2e by 2020 and 164 MtCO2e by 2030 compare to BAU levels (MNRE, 2019). The policy reduces energy-related emissions, but not process-related emissions. This policy has not been quantified in the current policy projections as we do not know the baseline used.

The VNEEP3 (2019-2030) sets energy efficiency targets for the industry sector, to reduce average energy consumption in subsectors compared to the 2015-2018 levels (MOIT, 2019). For example, the chemical industry has a target to reduce average energy consumption by at least 10%, and the cement industry has a target to reduce average energy consumption to produce 1 tonne of cement from 87kgOE in 2015 to 81 kgOE in 2030 (MOIT, 2019). VNEEP3 sets targets for newly built industrial parks to apply energy efficiency and conservation solutions by 2025 among other targets (MOIT, 2019).

Transport

The transport sector accounted for 23% of the total final energy consumption in Viet Nam in 2018 (APEC, 2022). Under Reference Scenario of APEC Energy Demand and Supply Outlook (2022), energy demand for transport represents a sharp increase and increase by three times from 2018-2050. Oil is the dominant energy source for transport, which accounted for 91% of the energy demand of this sector in 2018 and continued to be remain so until 2050 under Reference scenario of APEC Energy Demand and Supply Outlook 2022 (APEC, 2022). The VNEEP3 (2019-2030) aims to develop and implement energy conservation practice standards for all transport vehicles (APEC, 2022; MOIT, 2019).

In July 2022, Viet Nam adopted a roadmap for transition to green energy of the transport sector with electrification and use of green energy (Vietnam Government, 2022a). According to this roadmap by 2050 100% of Viet Nam’s transport sector will be operated through electricity or green energy. Particularly for the urban transport this roadmap outlines that by 2025 new buses will be using electricity or green energy, by 2030 all new taxi will be electric vehicle, by 2050 100% buses and taxis will be either electrified or will use green energy. This roadmap also outlines the interim targets for electrification of railways and shipping.

This road map also promotes blending and use of E5 gas for 100% of road motor vehicles. The government has a roadmap to mix A92 gasoline with at least 5% bioethanol, and compulsory energy labelling for LDVs and motorcycles, which is projected to encourage some renewables (4.6%) and electricity (minor levels) by 2050 (APERC, 2019).

Motorcycles are the main mode of transport in Viet Nam: 87% of households own at least one motorcycle (WorldAtlas, 2019). In 2013, Viet Nam aimed to limit the number of motorcycles and cars to 36 million and 3.5 million by 2020 (Investvine, 2013). However, as of 2022, the registered number of two wheeler has already reached 65 million and roughly two-third of the population currently own a motorcycle (Nguyen, 2022).

Viet Nam’s two-wheeler market is significant, ranking the second biggest in South East Asia (after Indonesia) and fourth in the world behind India, China, and Indonesia (VnExpress International, 2020). The electric two wheeler market is also growing fast in Vietnam and it has the second highest electric two wheeler market in the world, after China (MotorcyclesData, 2022).

Sales of electric two wheeler have increased significantly in recent years, from 163,428 vehicles in 2019 to nearly 237,000 vehicles in 2020 (an increase of 45%) (Le et al., 2022). The manufacture and adoption of electric vehicles have been given preferential treatment by the Vietnamese government.

To reduce energy use of this sector the National Strategy for Climate Change to 2050 has also put forward measures for restructuring the transport market, including the transition from road transport to inland waterway and coastal transport; make the transition from road to railway, increase railway goods transport percentage; increase transport efficiency via building and expanding road network.

Buildings

Energy demand in the building sector has risen in the past decade as result of Viet Nam’s successful implementation of universal electrification and increase in use of electrical home appliances (APEC, 2022; APERC, 2019). In recent times use of biomass has seen a significant drop because of increase electrification (APEC, 2022). The residential sector accounts for 18% of the total final energy consumption in 2017 (IEA, 2019). The government has introduced some energy efficiency policies, including the VNEEP3 (MOIT, 2019). An official Prime Minister Decision (No.04/2017/QD-TTg) in 2017 sets out mandatory energy labelling and minimum energy efficiency standards roadmap for equipment and appliances (MOIT, 2019). In the National Green Growth Strategy there are specific tasks relating to the development of green buildings, and energy efficiency of buildings (MNRE, 2019).

Agriculture

In 2021 agriculture represented 17% of Viet Nam’s GHG emissions (Gütschow et al., 2022). Energy demand in the agriculture sector is considered in the current policy scenario. An official Decision by the Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development approved a program to reduce GHG emissions in the agriculture sector to 2020, promoting low carbon agriculture (MNRE, 2019). In 2016, the Minister also approved the Action Plan to Respond to Climate Change of Agriculture and Rural Development for 2016-2020 with a vison to 2050, including mitigation projects to reduce emissions (MNRE, 2019). The Green Growth Action Plan (2017) aims to achieve an emissions reduction of 20% from the sector by 2020 below 2010 levels (MNRE, 2019).

The National Strategy for Climate Change to 2050 calls for a 43% emissions reduction from this sector from its 2030 BAU level and limit the emissions at 64 MtCO2e by 2030 from current level of 76 MtCO2e. Under broad measures and action in the agricultural sector this strategy has also proposed promoting agricultural restructuring, adopting smart agricultural solutions adapting to climate change and utilising advantages of tropical agriculture and develop organic agriculture. In the short run until 2030, Viet Nam’s focus would be on shifting cultivar and domestic animal compositions to smartly adapt to climate change while securing food supply of its population.

Forestry

Viet Nam’s land use, land use change and forestry sector is currently a net sink. Viet Nam’s LULUCF sector is intended to play a large role in meeting Viet Nam’s updated NDC. Under the government reported business-as-usual scenario (BAU), the LULUCF sector is estimated to be a sink of 49 MtCO2e in 2030 (Vietnam Government, 2022c).

In its 2050 National Climate Change Strategy, Viet Nam has set a target for land use and forestry sector to reduce 70% of emission and increase 20% of carbon absorption and achieve a total sink capacity of 95 MtCO2e by 2030. Maintain forest coverage at 43% and ensure area of national forest; improve forest quality and sustainable forest management are also part of it (Vietnam Government, 2022b).

The 2017 Law on Forestry regulates the management of forests, and notes that an assessment is needed to limit forest loss and conserve the forests (MNRE, 2019). The National Action Programme on the Reduction of GHG Emissions Reduction of Deforestation and Forest Degradation, Sustainable Management of Forest Resources, and Conservation and Enhancement of Forest Carbon Stocks (REDD+) by 2030, was approved in 2017 (MNRE, 2019).

Waste

According to the 2050 National Climate Change Strategy emissions reduction from waste sector would be 60.7% by 2030 and 90.7% by 2050. This is supported by various policy planning such as implementing solutions for managing and reducing waste from production to consumption, expand responsibilities of manufacturers; increase reuse and recycling of waste. Viet Nam will also adopt advanced solutions in treating wastes and wastewater to reduce methane emissions (Vietnam Government, 2022b).

In 2014, the waste sector represented 7% of emissions (excluding LULUCF) (MNRE, 2019). In 2018 the Prime Minister approved the National Strategy for General Management of Solid Waste to 2025 with a 2050 vision, which included energy recovery and GHG reduction (MNRE, 2019).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter