Policies & action

The CAT rates Brazil’s policies and action as “Insufficient”. Brazil’s emissions (excluding emissions from the forestry and land sector) have steadily increased over the past decades but are expected to essentially plateau under current policies, growing only slightly until 2030. Yet, Brazil needs to cut its emissions this decade to meet its 2030 target and for 1.5°C compatibility.

The “Insufficient” rating indicates that Brazil’s climate policies and action in 2030 need substantial improvements to be consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C. If all countries were to follow Brazil’s approach, warming would reach over 2°C and up to 3°C.

Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against modelled domestic pathways and fair share) can be found here.

Policy overview

In October 2022, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was elected president of Brazil for the third time, defeating former president Jair Bolsonaro. He assumed the presidency in January 2023, quickly moving away from the previous administration’s policies and reconstructing the country’s environmental policy which had suffered from budget cuts and policy rollbacks (Nature, 2023). Some positive policy developments can already be highlighted, including:

- Following the resubmission of its NDC in October 2023, the Inter-ministerial Council on Climate Change began reviewing the National Climate Change Policy (PNMC), which will now include sectoral mitigation and adaptation strategies covering the period up to 2035 as well as indicative sectoral targets for 2030 and 2035, a process that could take up to two years (Talanoa, 2023).

- Recent studies reported deforestation rates falling in response to political action (BBC, 2024; Global Forest Watch, 2024). A 36% drop in primary forest losses in Brazil in 2023 compared to 2022 levels was celebrated as an example of the effects of re-establishing law enforcement in the forestry sector. However, deforestation remains higher than in the early 2010s, with negative trends in some regions like the Cerrado where deforestation actually increased by 6% in 2023 (BBC, 2024; Nature, 2023)

- Brazil's presidency of the G20 summit in 2024 and hosting of COP30 in 2025 highlight its renewed engagement with the international community on environmental issues, signalling its commitment to shaping international climate policy. This isparticularly relevant as 2025 will be the year when countries are mandated to submit updated and more ambitious 2035 climate targets under the Paris Agreement.

- The development of new policies such as the Ecological Transformation Plan (PTE) to promote sustainable development while reducing Brazil’s overall environmental footprint, and which includes energy transition as one of its six pillars of action (Government of Brazil, 2023d; Talanoa, 2023).

However, there are still important and inconsistent elements in the new policy development that raise concerns about the prioritisation of sustainability and environmental goals within Brazil's infrastructure agenda, which cast serious doubt on the government's commitment to ecological transformation and transition away from fossil fuels (Nature, 2023), in particular:

- Brazil’s Novo PAC (a new USD 350bn growth acceleration programme designed to stimulate private and public investments in infrastructure, development and environmental projects) which assigned around USD 110bn (just over 30%) of its budget to “energy transition and security” while earmarking 63% of its budget for the oil and fossil gas industries, mainly for the production and development of these fossil fuels (Government of Brazil, 2023c, 2023e).

- The actions outlined under the energy transition pillar of the PTE focus mostly on reducing transport emissions by electrification or low-carbon fuels and further development of wind and solar energy; without concrete targets related to a transition away from fossil fuels.

- Brazil is yet to put forward a timeline for phasing out fossil fuels and questions remain as to how it will achieve an energy transition in a just and equitable way (Nature, 2023).

Our calculations show Brazil’s total emissions (excluding LULUCF) will reach between 1,162 MtCO2e and 1,197 MtCO2e in 2030 under current policies, almost 25% above 2005 levels. Brazil is not on track to reach neither its 2025 target nor its 2030. To peak and then rapidly decrease emissions, as required in order to limit warming to 1.5°C, Brazil will need to sustain and strengthen policy implementation and accelerate mitigation action in all sectors— including a reversal of present plans to expand fossil fuel energy sources.

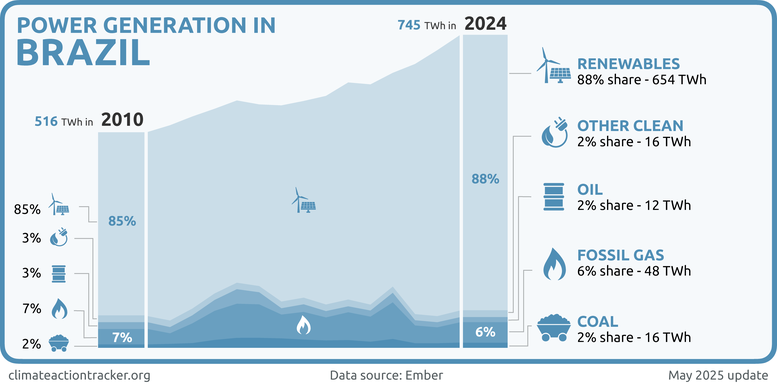

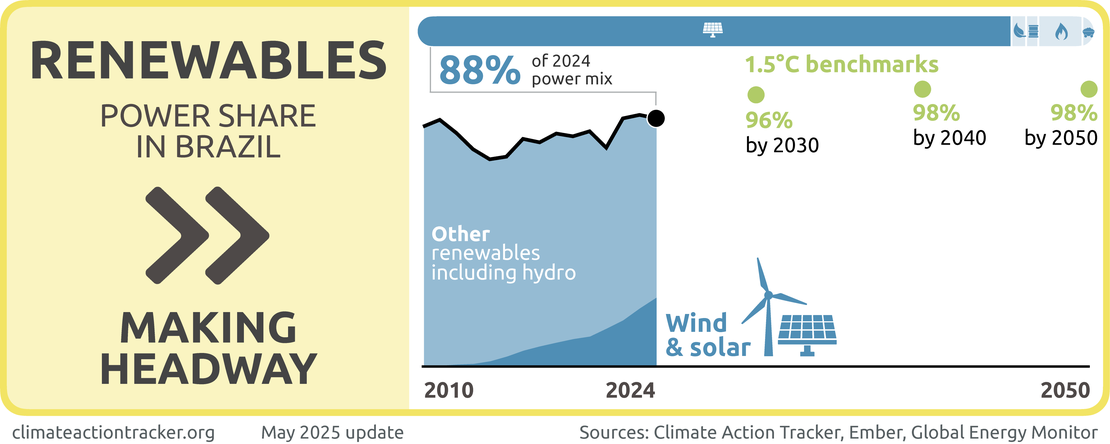

Power sector

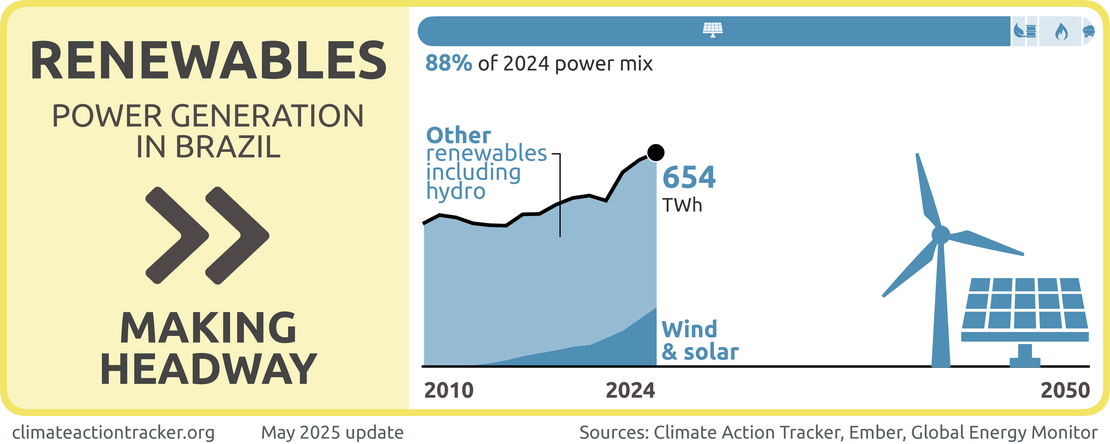

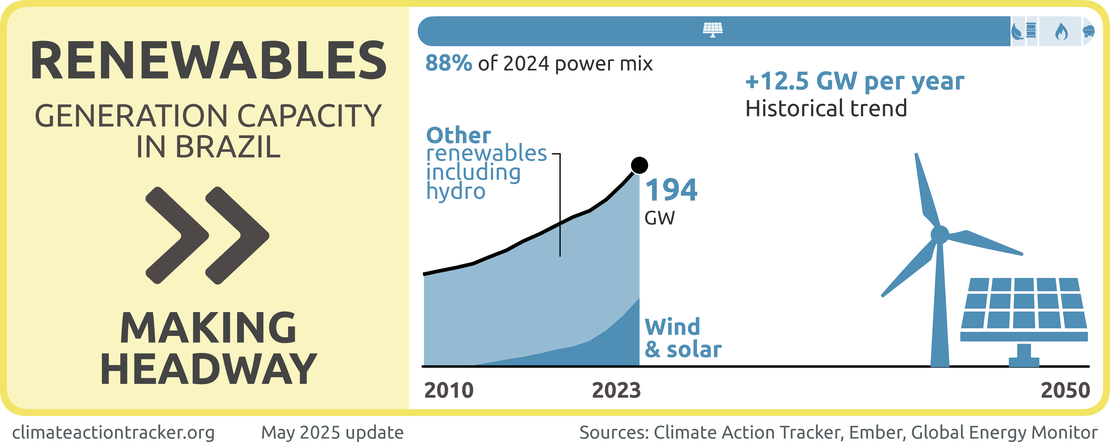

Brazil’s power sector is dominated by renewables which represented almost 90% in 2024 making Brazil’s power grid one of the world's cleanest. Though the high share of renewables is primarily due to hydroelectricity in the system, Brazil has significantly ramped up wind and solar deployment in the last five resulting in an increase in the share of wind and solar in power generation from about 11% to 25%. Fossil gas, coal, oil and nuclear make up the remaining 10% of electricity generation. The historical reliance on hydropower has exposed vulnerabilities as Brazil faced historic droughts that have led to decreased hydro power generation but instead of planning to replace this with other renewable sources, the government plans to also increase fossil fuel use (Ministry of Mines and Energy, 2022; Talanoa, 2023).

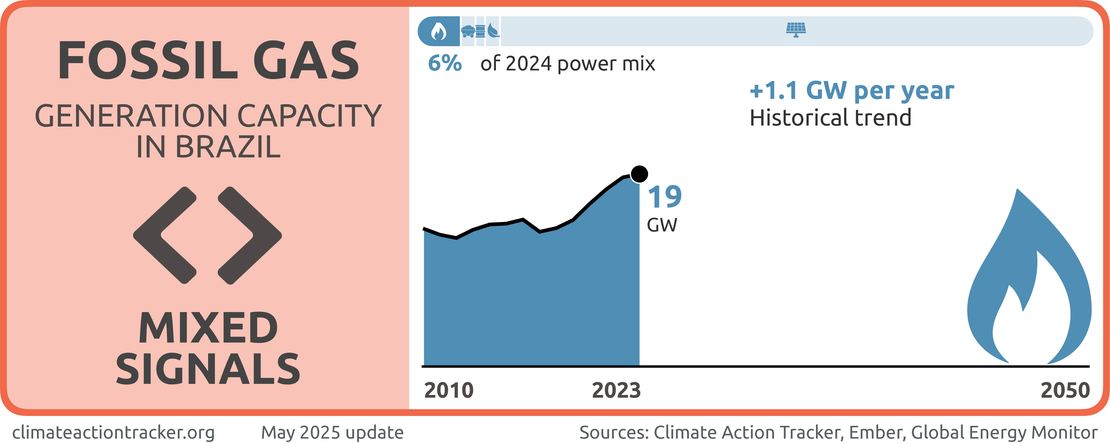

According to the 2031 ten-year energy expansion plan (PDE 2031), hydropower capacity in Brazil's electricity system would steadily decrease from 83% in 2000 to 46% by 2031. Under the PDE, Brazil plans to diversify its power mix through investments in other renewables (wind, biomass, and solar), but also in fossil gas power plants (Ministry of Mines and Energy, 2022). This planned expansion of fossil gas generation is not aligned with 1.5°C, which needs to see coal phased out by 2030 and gas by 2035. Recent scientific literature highlights that there is no room for investment in new oil, gas, and coal activities if global warming is to be limited to 1.5°C (Green et al., 2024). Increasing fossil gas capacity is thus in stark contrast with Brazil’s aspiration to position itself as a climate leader ahead of hosting COP30 in 2025.

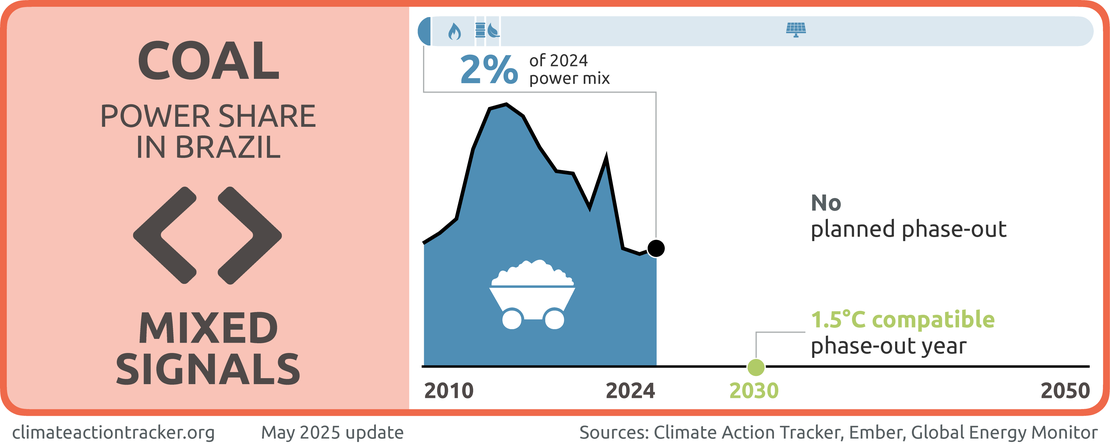

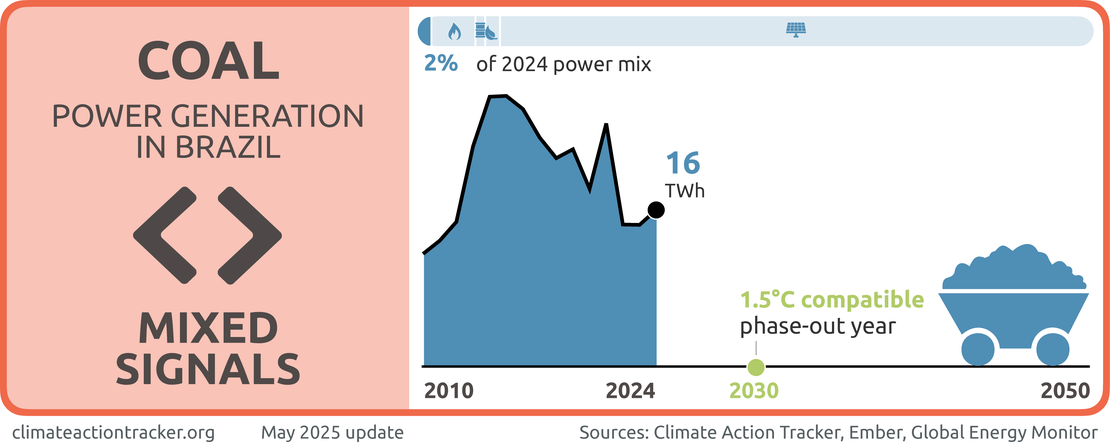

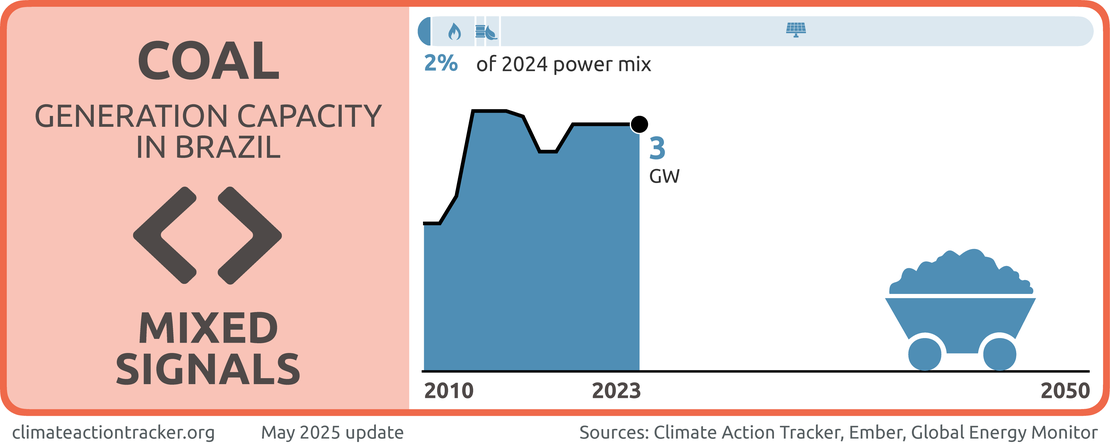

Coal

Coal represented 2% of Brazil's electricity generation in 2024 and it’s share has been decreasing over the last five years at a rate of about 0.3% per year. Despite its small and decreasing share in the power mix, we evaluate progress in this sector as sending "Mixed signals" given Brazil actually plans to expand coal capacity in the near future, does not yet have a coal phase-out target and has not adopted COP26's initiative to transition away from unabated coal power and to cease building new plants. To be 1.5°C compatible, Brazil would need to phase out coal in power generation by 2030.

At COP28, Brazil joined the Global Renewables and Energy Efficiency pledge which also highlights the need for a phase down of unabated coal power, in particular ending investment in unabated new coal-fired power plants (UNFCCC news, 2023). Brazil remains the second-largest user of coal for power generation in the region (IEA, 2024a).

Coal power in Brazil is highly reliant on government subsidies, which are set to expire in 2027 (Inesc, 2022). Brazil’s Ten-Year Energy Expansion Plan (PDE 2031) includes modelling studies that show that most coal capacity could exit the system in 2027 and 2028 as power contracts and subsidies expire (PNME, 2023). However, the same document also proposes the expansion of 350 MW/year of coal-fired power projects, between 2028 and 2031, through the modernisation of the existing plants or their replacement with more modern ones. This would bring back an overall 1.4 GW of coal capacity into Brazil’s energy mix by 2031 (Ministry of Mines and Energy, 2022).

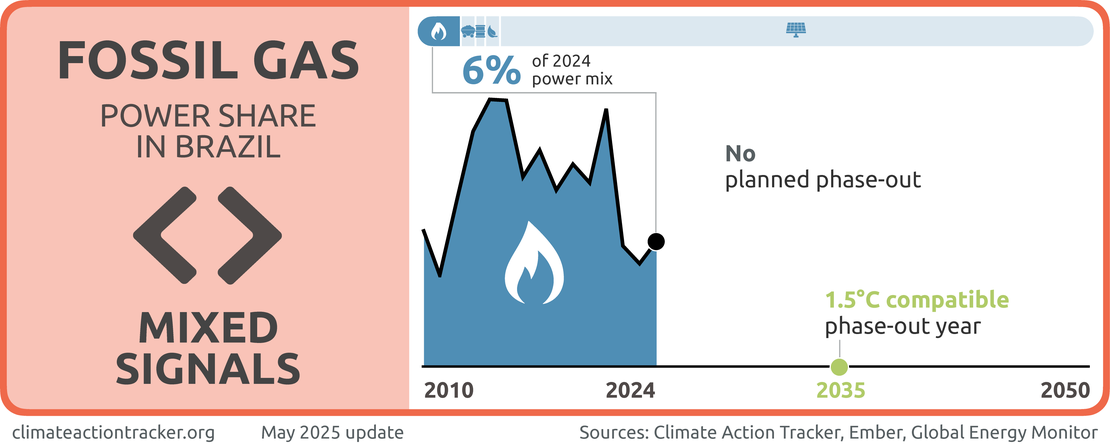

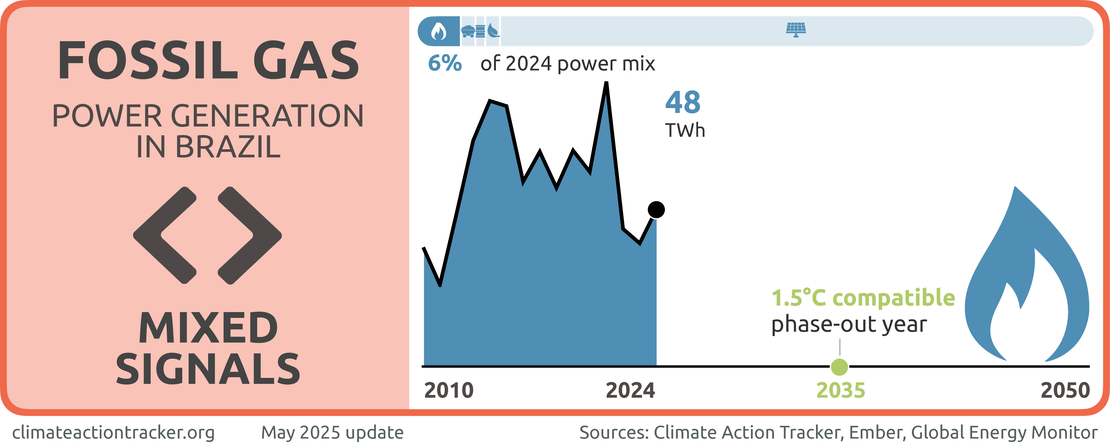

Fossil gas

Gas represented 6% of Brazil's electricity generation in 2024, a decrease from the average 8% over the last five years. Despite this recent decrease in fossil gas generation, Brazil is planning on significantly expanding its fossil gas fleet. There are 41 GW of fossil gas and oil power plants, either announced or in pre-construction phase in Brazil, with over 4 GW currently under construction (Global Energy Monitor, 2024). The 2031 ten-year energy expansion plan (PDE 2031) proposes the diversification of Brazil's energy matrix, complementing investments in renewable sources with fossil gas power plants. As well as expanding fossil gas electricity generation, the government is planning on expanding oil and fossil gas production. For further details on the oil and gas production industry in Brazil, see the industry section below.

Expanding fossil-based generation risks Brazil losing out on its considerable potential for renewable power generation, and is not compatible with 1.5°C. To be 1.5°C compatible, Brazil would need to phase out fossil gas from power generation by 2035 but to date, Brazil does not have a fossil gas phase-out target (Climate Action Tracker, 2023).

We evaluate progress in this sector as sending “Mixed signals” due to the combination of decreasing fossil gas generation, the planned expansion of capacity and the lack of a phase out target.

Renewables

Renewables have consistently contributed to over 80% of Brazil's electricity generation, with figures reaching 88% in 2024. Electricity generation from wind and solar in Brazil has also increased rapidly over the last five years. This steep increase comes from the significant ramp up of wind and solar from about 11% of the power mix in 2020 to 25% in 2024. This is on top of the already large share of hydropower in the country, though this share has been decreasing due to the severe droughts that Brazil has faced in recent years.

Renewables are highly competitive in Brazil, with recent auctions delivering contracts to renewable projects only, and wind and solar generation are set to grow rapidly under current policies and market conditions (IEA, 2024b). Much of the capacity expansion planned in Brazil is wind and solar: Brazil’s Novo PAC aims to have 80% of the added electricity capacity coming from renewable sources. However, renewable deployment needs to be further accelerated and delivered alongside a fossil fuel phase-out. By maintaining current hydropower generation, and increasing wind and solar energy to meet electricity demand growth and displace the remaining fossil fuel generation, Brazil could decarbonise its power sector. To be 1.5°C compatible, Brazil would need to continue to increase the deployment of renewables reaching 96% of the power share in 2030 and a slightly higher 98% in 2040.

While renewable expansion is progressing well, it needs to be supported by policy and delivered alongside a fossil fuel phase-out to be fully compatible with 1.5°C pathways. We evaluate progress in this sector as "Making headway" due to fast, increasing rollout in wind and solar capacity.

Industry and fuel supply

In 2022, industrial emissions accounted for nearly 10% of the nation's total emissions (excluding LULUCF) (Gütschow et al., 2024). Additionally, direct and indirect emissions from Brazil's industrial sector contribute 27.4% and 4.3% of energy-related CO2 emissions, respectively (Climate Transparency, 2022). While there is progress in the power sector, policies to curb emissions from sectors like steel, cement, and oil and fossil gas continue to be limited, and tend to focus mostly on promoting economic development.

Brazil’s new government uses the term "neo-industrialisation" to emphasise the urgency to lay new foundations for the sector's growth. However, policies such as the “New Brazil Industry” focus mostly on economic development rather than pushing for a green transition in the sector. Even though the new growth acceleration programme — called Novo PAC —claims to signal a shift towards green neo-industrialisation, the same programme also designates significant funds to the oil and gas industries (see below for more details).

Oil and gas industries

As outlined in multiple federal government planning documents, Brazil intends to expand its oil production until at least 2029 while fossil gas production is expected to maintain its high levels well into the next ten years (Talanoa, 2023). The 2050 National Energy Plan, a long-term planning instrument, projects an increase in demand for oil derivatives by that year. According to this plan, Brazil will remain a major producer of oil and fossil gas (Talanoa, 2023). At the same time, Brazil’s new growth acceleration programme (Novo PAC) has earmarked more than 60% of the investments for “energy transition and security” to oil and gas, specifically for the production and development of these fossil fuel industries (Nature, 2023).

Brazil was the world’s ninth-biggest oil producer in 2022 and the eighth-largest consumer of petroleum products. Brazil has policies in place that aim at making Brazil the world’s fourth-largest oil producer until the end of this decade (Nature, 2023). At COP28, Brazil’s energy minister decided to announce that Brazil plans to align itself more closely with OPEC+, a group of oil-producing countries (Reuters, 2023).

According to the IEA’s latest net-zero roadmap, which outlines pathways to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, there is no room for any new oil, fossil gas, and coal exploration if global warming is to be limited to 1.5°C (IEA, 2023a). Therefore, Brazil’s oil and gas industry developments are in stark contrast with the 1.5°C temperature limit of the Paris Agreement and with Brazil’s aspiration to position itself as a climate leader ahead of COP30.

Transport

Transport makes up just over 50% of Brazil’s energy sector emissions, and emissions have been steadily increasing since 2018, mainly due to increased vehicle ownership (SEEG, 2023a).

As part of its energy transition goals, Brazil launched the Fuels of the Future Programme which plans to increase the ethanol blend in gasoline from 22% to 27%, as well as the amount of biodiesel blended into diesel from 14% to 20% by 2030. The programme also looks at reducing aviation emissions by gradually increasing the mix of sustainable fuels and stipulates that airlines must reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 1% in 2027 and by 10% in 2037 (Silva, 2024; Talanoa, 2023). Brazil is currently one of the world’s largest producers and consumers of biofuels. If the bill is approved by the Senate later this year, this programme would boost the ethanol industry in the country.

However, it's essential to ensure that biomass used in future energy systems is sustainably sourced. This means preventing upstream emissions from land-use changes, avoiding competition with food crops, protecting biodiversity, and respecting the rights of indigenous peoples in that land (Energy Transitions Commission, 2021). Furthermore, while biofuels may have reduced the emissions intensity of the road transport sector in Brazil, the potential for further reductions in emissions by biofuel blending is limited (ICCT, 2023). Instead, full decarbonisation of the transport sector will require fast uptake of electric vehicles (EVs). Brazil has not set a specific target for electric vehicles and has not joined the COP27’s Accelerating to Zero coalition (A2Z), which states that 100% of new car and van sales in 2040 should be electric vehicles, 2035 for leading markets.

According to the third yearbook on electric mobility, the sale of EVs has grown significantly in recent years. According to the latest estimates, around 2.5% of light-duty vehicles sold in 2022 were electric. The number of EVs sold in 2023 almost doubled compared to the previous year, a positive development that surpassed all projections (Audi, 2024; PNME, 2023). However, despite these positive development, there is still a long way to go. For comparison, the 1.5°C compatible share of EV sales in Brazil would need to be above 45% by 2030 (see figure below). Increasing electrification of the transport sector would also reduce Brazil’s dependency on biofuels, particularly those produced from soy, thereby reducing pressure on Brazilian land for soy farming (PNME, 2023).

EV market share

Agriculture

Agriculture is the second biggest contributor to Brazil’s GHG emissions after the land use sector (LULUCF), with emissions consistently growing over the years and reaching its highest reported levels in 2022 at just over 600 MtCO2e. Excluding LULUCF emissions, agriculture and livestock represent just over half of the country’s emissions. Almost 75% of the sector’s emissions are methane and nitrous oxide from livestock alone (SEEG, 2023a). If the indirect emissions of the agriculture sector (mostly related to deforestation resulting from the expansion of agricultural land) were considered, the sector would be by far the single largest emissions source in Brazil.

However, there are limited policies in place to reduce agricultural emissions. Brazil’s main policy instrument of agricultural activity is the Agricultural Plan (Plano Safra) which aims to facilitate sustainable development by providing credit lines tailored to support crop production and product marketing (CPI, 2023). The Plano Safra for 2023/2024, with a record allocation of BRL 435bn for agricultural financing, designates only 0.5% of this sum for low-carbon measures in the sector (Talanoa, 2023). Furthermore, the new Safra Plan 24/25, unveiled in the first half of 2024, has a 16.5% increase in investment credit lines. This the largest increase in public resources the Safra Plan has received so far (Government of Brazil, 2024).

Renovagro, formerly known as ABC+ Plan, supports low-carbon agriculture by financing practices such as land restoration, integrated crop-livestock-forest systems, the production of bio-fertilisers, and others. The ABC+ Plan aims to prevent over one billion tonnes of carbon emissions between 2021-2030, primarily through restoring degraded pastures and planting forests.

The Brazilian agricultural sector is heavily dependent on fertilisers. In November 2023, the government approved the revised National Fertiliser Plan 2050 aiming to reduce the country’s dependence on fertiliser imports — currently at 87% of total demand — and meet 45% to 50% of the demand domestically by 2050. The plan outlines strategies such as reactivating idle factories, incentivising new industrial plants, and investing in sustainable nutrient production to achieve the goal.

Historically, there is a strong relationship between agriculture expansion and deforestation emissions in Brazil. Forest land is consistently lost to make room for agriculture and cattle ranching. The expansion of soybean plantations became a direct driver of deforestation as it became more financially attractive than cattle ranching (Ionova, 2021). Forests are either directly converted to soybean farms, or soybeans are planted on old pasture, driving deforestation for more pastureland (Kimbrough, 2021).

However, expanding the agriculture frontier through deforestation is unnecessary to increase productivity. Brazil has considerable potential to add value and productivity to already available but currently underutilised land by investing in more sustainable and efficient agriculture methods (Observatório do Clima, 2019; Stabile et al., 2020).

Forestry

Inventory emissions data available shows that the land use and forestry sector has been by far the largest source of GHG emissions in Brazil since the early 1990s. The year 2019 saw an area of over one million hectares deforested in the legal Amazon — 34% larger than in 2018, and 120% larger than the historical low reached in 2012 (INPE, 2020). In 2021, emissions from land use changed reached a new high — 10% higher than those reported for 2019 (SEEG, 2023a). The high deforestation rates are linked to a weakening of Brazil’s institutional and legal frameworks for environmental protection carried out by the previous administration. Weak land tenure enabled land grabbers to occupy and, in many cases, deforest undesignated public forests.

Preventing and combating deforestation stands as the biggest challenge for Brazil’s new administration. In this context, the Lula government launched a new edition of the Action Plan to Prevent and Combat Deforestation in the Legal Amazon (PPCDAm) in June 2023, with a target to reach zero deforestation by 2030. With deforestation in the region projected to decrease by 75% to 80% by 2027 under this plan, Brazil aims to reverse the alarming trends observed, including the loss of 27,800 km2 of forest in 2021, marking the second-highest rate in history (Government of Brazil, 2023a; Talanoa, 2023).

This change in policy focus in Brazil's government is already yielding results. Recent studies reported a 36% drop in primary forest loss in Brazil in 2023, compared to 2022. However, deforestation still remains higher than in the early 2010s, with negative trends in some regions like the Cerrado region where deforestation actually increased by 6% in 2023 (BBC, 2024; Nature, 2023). The new PPCDAm includes a goal to reach zero deforestation by 2030 in the Cerrado, the region where the country’s agricultural land is expanding and the source of numerous major river basins, vital to the nation's water resources. In 2021, Brazil signed the COP26’s forestry pledge “to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030”.

Meeting Brazil’s NDC target will require that efforts to halt deforestation are accompanied by extensive reforestation and restoration of native forests. This can help Brazil to transition towards scenarios where the land use sector not only reduces emissions but also actively removes carbon from the atmosphere (Government of Brazil, 2023a; Talanoa, 2023).

Methane

Brazil signed the methane pledge at COP26. At the time of joining the pledge, Brazil stood as the world's sixth-largest emitter of methane. Close to 30% of Brazil’s total GHG emissions incl. LULUCF are from methane, with more than 75% coming from agricultural activities, followed by energy and waste.

In March 2022, the federal government launched the ‘zero methane’ programme. However, it focuses primarily on actions to reduce emissions in the waste sector and to use methane for energy use, such as biogas and biomethane. In some sectors, such as meat production, this initiative was not well received. The Ministry of Agriculture stated that this measure would affect the economic growth of the sector. To date, Brazil lacks a public policy roadmap to guide its efforts in achieving the necessary methane reduction to fulfil its international commitment.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter