Policies & action

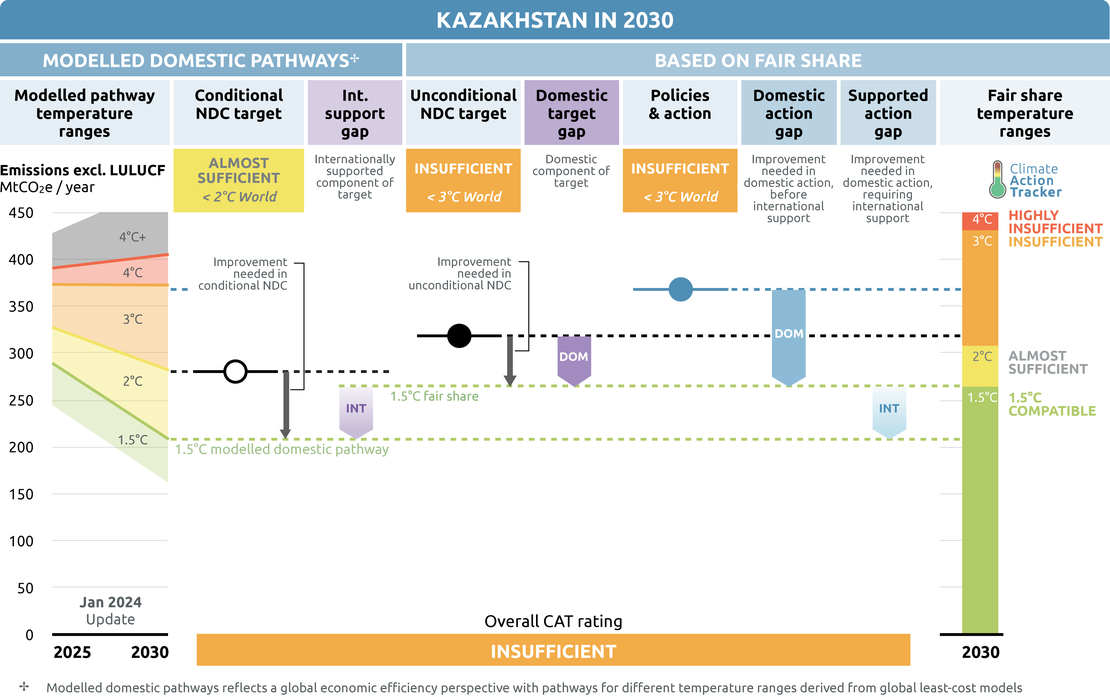

Kazakhstan’s rising emissions trajectory shows that its climate policies are not in line with its own emission reduction targets and global warming limits. We rate Kazakhstan’s current policies as “Insufficient” when compared to their fair share contribution as this metric is slightly favourable than the modelled domestic pathways. The “Insufficient” rating indicates that Kazakhstan’s climate policies and action in 2030 need substantial improvements to be consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C. If all countries were to follow Kazakhstan’s approach, warming would reach over 2°C and up to 3°C.

Policy overview

Kazakhstan’s emissions under current policies are projected to continue increasing, in contradiction to its NDC and net zero targets. According to our analysis, Kazakhstan’s policies will result in emissions increasing from 338 MtCO2e in 2021 to 368 MtCO2e in 2030 (excluding LULUCF). This amounts to a decrease in emissions relative to 1990 (base year for NDC target) of only 4.9%. As such, Kazakhstan will miss both its unconditional and conditional NDC targets.

Kazakhstan’s policies in the energy sector pull in different directions. On the one hand, the government plans further development of and investment in fossil fuels, which account for 98% of primary energy supply. These plans include the construction of new coal power plants, gassification of older coal plants and expansion of gas as a “transition fuel”, exploration and ramping up oil production.

On the other hand, policies to support renewable energy led to a marked uptick in renewable energy generation capacity in the past five years. In the power sector, shares of renewable energy – excluding old hydro-power plants – reached 4.5% in 2023, on track with the government's modest targets. Similarly, energy efficiency policies have contributed to a declining trend in the economy's emissions intensity. However, the balance between policies that support emissions growth and those supporting mitigation remains skewed to the former.

Significant additional efforts are needed to translate Kazakhstan’s net zero strategy into equivalent and actionable climate policies and programmes. New policies will be needed to increase the strength of the overall policy framework, but there are also opportunities to build on existing climate policies and institutions.

Recent examples already delivering impacts include amendments to the 2009 Law on supporting the use of renewable energy sources, which established the legal basis for the auction mechanism used to procure renewable energy, and the 2021 update of the Environmental Code, which ramps up the “polluter pays” principle by, for instance, giving the 50 largest companies, which account for 80% of the country’s GHG emissions, until 2025 to adopt the best available technologies (BATs) (Shayakhmetova, 2021).Further stringency enhancements to the Emissions Trading System (ETS) are a key opportunity area for building on existing climate institutions.

Sectoral pledges

In Glasgow, a number of sectoral initiatives were launched to accelerate climate action. At most, these initiatives may close the 2030 emissions gap by around 9% - or 2.2 GtCO2e, though assessing what is new and what is already covered by existing NDC targets is challenging.

For methane, signatories agreed to cut emissions in all sectors by 30% globally over the next decade. The coal exit initiative seeks to transition away from unabated coal power by the 2030s or 2040s and to cease building new coal plants. Signatories of the 100% EVs declaration agreed that 100% of new car and van sales in 2040 should be electric vehicles, 2035 for leading markets. On forests, leaders agreed “to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030”. The Beyond Oil & Gas Alliance (BOGA) seeks to facilitate a managed phase out of oil and gas production.

NDCs should be updated to include these sectoral initiatives, if they're not already covered by existing NDC targets. As with all targets, implementation of the necessary policies and measures is critical to ensuring that these sectoral objectives are actually achieved.

| Kazakhstan | Signed? | Included in NDC? | Taking action to achieve? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methane | Intends to | No | Not applicable |

| Coal Exit | No | No | Not applicable |

| Electric vehicles | No | No | Not applicable |

| Forestry | Yes | No | Yes |

| Beyond oil and gas | No | No | Not applicable |

- Methane pledge: Kazakhstan has not signed the methane pledge. However, it has indicated an intention to join it, repeated by the President in his address to COP28, and has two relevant policy programmes in development: the National Methane Emissions Inventory and Reduction Programme, and Fugitive Methane Emissions and Carbon Intensity Reduction Programme (IEA, 2023). In 2022, methane accounted for over 12% of GHG emissions - arising mainly from processes of extraction, transportation, handling / storage of fuel, biodegradation of organic waste, and livestock (Republic of Kazakhstan, 2023). Methane leakage risks from gas pipelines will increase if fossil gas production increases as expected (IEA, 2022). In 2023, Mangistau in Kazakhstan was the sight of a “ultra-emitter” methane leak which will likely prove to be the biggest in the world in 2023 and may be the largest in history.

- Coal exit: Kazakhstan only endorsed Clause 4 of the coal phase-down pledge at COP26, which focuses only on financial, technical, and social support for a just transition. To date, there is no clear plan or commitment for coal phase out in Kazakhstan even though coal accounts for over 55% of national net emissions. In 2020, almost 70% of electricity and 99% of heat were produced from coal combustion.

Coal is also used in industrial processes, such as iron and steel production, and is mined for export. Kazakhstan announced plans for new coal power plants in 2022 while several mines have announced plans for increased production or expansion (Babajeva, 2023). The government has not indicated any intention to move towards limiting permit issuances and construction of new coal power plants or mines. Under current policies, coal will remain one of Kazakhstan’s main energy sources past 2030 (Republic of Kazakhstan, 2019).

- Forestry: Kazakhstan signed the forestry pledge at COP26 in 2021, committing to the goal of halting and reversing forest loss and land degradation by 2030, and announced a goal of planting over two billion trees by 2025 (Prime Minister of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 2021). Kazakhstan had previously pledged to restore at least up to 1.5 million ha of degraded land through afforestation and reforestation by 2030 under the Bonn Challenge, to which it became a signatory in 2018. The LULUCF sector is currently a minor emissions source in Kazakhstan. Emissions from the sector are attributed to croplands rather than forest conversion, and have been declining since the mid-2000s (Republic of Kazakhstan, 2022).

- Beyond oil and gas: Kazakhstan did not join the ‘Beyond Oil & Gas’ initiative launched at COP26 to end oil and gas exploration and production. Along with coal, the Kazakhstan economy is heavily reliant on oil and gas not only for domestic use (oil fulfils 41% of national primary energy consumption, coal just under 30%, and fossil gas almost 8%) but also for export earnings. The government plans on the expansion of oil and gas consumption, with fossil gas identified as an “intermediate” fuel for the energy transition. There are no explicit plans in place for phasing down the production or consumption of these fuels, aside from general emissions reduction targets (Republic of Kazakhstan, 2019).

Energy

The decarbonisation of Kazakhstan’s energy industry is complicated by its significant fossil fuel resource endowments, which are used internally and exported. In 2020, fossil fuels accounted for just over 98% of total primary energy supply (50% coal and others, 31% gas, 18% coal) and renewables accounted for just under 2% - mainly hydro (IRENA, 2023) . Kazakhstan is a major fossil fuel exporter in the region, with 66% of fossil fuel production exported in 2020 (IRENA, 2023). In terms of consumption, oil fulfils 41% of national primary energy consumption, coal just under 30%, and fossil gas almost 8%.

Climate policy ambition and progress has been slow in the energy supply sector to date. Further fossil fuel development and investment are still being planned, including construction of new coal power plants, gassification of older coal plants, exploration, and ramping up oil production. The energy supply industry accounted for over 80% (90% fossil fuel combustion/10% fugitive emissions) of Kazakhstan’s annual GHG emissions in 2020 (Republic of Kazakhstan, 2022). Oil and gas production alone accounts for 2.7% of national emissions – more than LULUCF or Waste sectors (Republic of Kazakhstan, 2023).

Kazakhstan’s steps towards further exploitation of fossil resources are inconsistent with its net zero target, fails to acknowledge the short-term steps necessary to keep the window open for a 1.5°C-consistent GHG emissions pathway, and risks deeper carbon lock-in.

Fossil fuels

Kazakhstan is among the top 20 countries globally in terms of coal, oil, and gas reserves and exports: In 2020, placing 10th for proved reserves and 9th for coal exports, 12th and 9th for oil, and 16th and 12th for fossil gas (BP, 2023). Around 80% of its oil is exported (IEA, 2022). Kazakhstan’s economy remains dependent on fossil fuel revenues. Oil and gas accounted for 17% of GDP in 2020 and 44% of the government’s budget (IEA, 2022).

Kazakhstan’s coal production and consumption have been relatively stable over the past 10 years. In 2020, coal combustion accounted for 55% of net emissions, almost 70% of electricity generation, and 99% of heat (with household coal consumption one of the highest in the world) (IEA, 2022). Coal is also used in industrial processes, such as iron and steel production, and is mined for export.

In 2022, the government announced plans to build new coal power plants and several mines have indicated plans for increased production or expansion (The Third Pole, 2023). There has been no indication that the government intends to move towards limiting permit issuances and construction of new coal power plants or mines. Under current policies, coal will remain one of Kazakhstan’s main energy sources past 2030 (Republic of Kazakhstan, 2019). Kazakhstan’s mitigation approach for the coal sector is limited to the modernisation of existing coal plants, as well as plans to replace coal with fossil gas.

President Tokayev has stated that the government was considering the complete phase out of all coal-fired power plants by 2050 at the earliest. This is completely out of line with the 2031 coal phase-out benchmark for Eastern Europe and Former Soviet Union, and the 2040 global benchmark (Climate Analytics, 2019).

Kazakhstan’s fossil gas consumption has almost doubled since 2013 and oil consumption has grown by almost 50% (BP, 2023). The government plans on the expansion of oil and gas sectors and has identified gas as an “intermediate” fuel for the energy transition, which is short-sighted considering that gas is not a long-term solution for the deep decarbonisation needed (Climate Action Tracker, 2017).

Short-term plans for oil production could see an increase of 15.8% compared to 2020 levels, at over 100 million tonnes, by 2025 (IEA, 2022). The government also plans to expand the energy sector to include coalbed methane exploration and production in the Karaganda region (kazinform, 2018) and in July 2019 signed a 15-year extension to the production sharing agreement of the Dunga fields, from 2024 to 2039, which will allow the production of an additional nine millions tons of oil (The Astana Times, 2019).

Kazakhstan has experienced fuel shortages in recent years, despite its vast resources and production exceeding demand. This is due to the persistence of artificially low prices, under-investment in network infrastructure and the energy industry, and perverse export incentives.

In response to energy shortages and efforts to rationalise prices, protests broke out across Kazakhstan in 2022, leading the government to reintroduce price caps and utilise export restrictions for the past two years (Fracassi, 2023). And yet, other measures to attract investment into the sector seem to reinforce existing drivers. For example, subsoil regulation amendments in 2023 include export customs and tax exemptions to support oil, fossil gas, and mining industries in various exploration and production activities (KMPG, 2023). Other measures to support these industries include a proposed gas union between Russia, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan (Mitrova, 2023).

Improving energy security is an important national priority, but the fossil fuel pathway involves significant risks – including those of a geopolitical nature. For example, Kazakh oil exports were throttled in Russian owned pipelines when the government did not support its invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Besides the closure of export routes, the incurred war risk insurance premium led to high prices that deterred buyers (O’Byrne, 2022).

Adding to this, transition risks should be of major concern as the emissions intensive economy may encounter trade restrictions or declining demand for important exports. With around 5% of the workforce employed in the energy industry, regional energy access and economic disparities, and sensitivity to energy price increases, the absence of policies for a just transition could compound these risks.

Renewables

Kazakhstan has globally competitive wind power resources and, as land is not constrained, solar potential is also significant. With enabling policies, this potential could see Kazakhstan becoming a major renewable energy producer and exporter in the region (World Bank, 2022). Renewables are primarily used in power generation, with hydropower accounting for 8% of generation in 2021, wind 2%, and solar 1%.

Despite an early start with the 2009 law on supporting the use of renewable energy, development on the ground has been slow. Amendments to the law first introduced feed-in tariffs in 2014 and then an auctioning mechanism in 2017. Alongside the 2013 Green Economy Concept target of 3% renewable energy in power generation (excluding hydro) by 2020, which Kazakhstan met, these policies have contributed to a marked uptick in renewable energy generation capacity in the past 5-years. Auctions have also contributed to significant cost declines.

Renewable’s share of power generation stands at around 4.5% in 2023, from 133 renewable energy facilities with an installed capacity exceeding 2,500 MW – mainly solar and wind (Nakispekova, 2023). This represents an almost trebling of capacity compared to the 900 MW installed in 2019 and a 20-fold increase since 2011. In 2021, the Government increased its 2030 renewable energy generation target from 10 to 15% by 2030 to reflect the changing energy landscape. This is a step in the right direction but not yet 1.5ºC compatible.

There is clearly support for renewables in Kazakhstan, including among citizens. According to a recent representative survey, conducted by the UNDP and the Ministry of Energy, over 90% of the public support government’s move to renewable energy resources (UNDP, 2023). However, the government will need to do more to create an attractive and enabling policy environment for investment – which has mainly come from international development banks - especially as competition from neighbouring countries like Uzbekistan increases (Kumenov, 2021a).

Increasing renewable energy targets, improving transparency of long-term power planning, and scaling up auctions, alongside strengthening grid management capacity and transparent long-term grid extension planning, are some areas where improvements could help to accelerate renewables growth.

Electricity

Power generation is dominated by coal and gas, which account for ~70% and ~20% respectively (IEA, 2022). Despite significant potential and recent gains, solar and wind still play a minor role in the power sector.

Much of Kazakhstan’s power grid and generation infrastructure is performing poorly, due to advanced age and significant wear-and-tear. For example, the bulk of Kazakhstan’s coal power capacity comes from plants that are more than 40 years old, the typical design life. According to the Ministry of Energy, a recent technical audit of coal plants found that most are not in good shape and will require increased finance for maintenance and repair (The Third Pole, 2023).

Since 2021, Kazakhstan’s cheap power prices and clamp-downs in other regions, notably China, caused an unexpected influx of crypto currency miners that placed unexpected strain on the already tight power system (Gordeyeva, 2021). Regulations have since been developed to help manage the situation, but power supply remains constrained and staggered power outages have been used to manage shortfalls (Eurasianet, 2023).

To address the supply shortage, the Ministry of Energy stated that an additional 19 GW of generating capacity is required by 2035 – with 10 GW from renewable energy sources (Ishekenova, 2022). Increasing the flexibility of the grid and power system will also be essential. The government has recently launched auctions for investments in new flexible generating capacity, including large gas-fired and hydropower projects (IEA, 2022). Kazakhstan also codified the use of waste to power technology, which is expected to reduce the volume of waste accumulated in landfills by 30% by 2025 (Nurbay, 2021).

Nuclear power

Nuclear is also being proposed as a means to decarbonising the power sector while meeting increasing demand. In addition to renewable targets, Kazakhstan’s 2013 Green Economy Concept set the following goals for the power sector: by 2030, 30% of power generated from renewable and alternative energy sources and, by 2050, 50% power generated from renewable and alternative energy sources, 30% gas, and a 40% overall reduction in CO2 emissions (Republic of Kazakhstan, 2015).

While Kazakhstan has no nuclear generation capacity, government officials have increasingly advocated for its inclusion in the energy mix. Kazakhstan hosts some of the world’s largest uranium deposits, and is the world’s largest uranium producer (International Trade Administration, 2022). In 2021, President Tokayev ordered the government to comprehensively assess the possibility of establishing a nuclear power industry in Kazakhstan (Abbasova, 2021). In 2023, he proposed a referendum on the question of whether nuclear power should be considered (Avdaliani, 2023). Kazakhstan’s fifth Biennial Report to the UNFCCC indicates 1.5 GW of nuclear in 2030 and 2 GW in 2050. Even if approved, it is unlikely that new nuclear will be commissioned in time to help Kazakhstan meet its 2030 targets.

Energy efficiency

Kazakhstan has one of the most energy intensive economies - 12th globally at 0.145 koe/USD15p -, although energy intensity has been declining since 1990 (Enerdata, 2023). Kazakhstan’s 2013 Green Economy Concept includes the following energy efficiency-related targets: decrease the energy intensity of GDP by 25% by 2020, 30% by 2030, and 50% by 2050 below 2008 levels (Republic of Kazakhstan, 2015, 2019). It has already achieved its 2030 target, with emissions intensity declining almost 40% between 2008 and 2022 (Enerdata, 2023). These targets are cross-sectoral in nature and range from initiatives for district heating to thermal renovation of houses, to energy standards and energy efficiency categories for buildings and household appliances (Republic of Kazakhstan, 2015). The updated 2021 Environmental Code stipulating that 50 major emitters need to adopt the best available technologies by 2025 could help reduce energy intensity significantly if enforced.

Carbon Pricing

After a temporary suspension, the ETS restarted operation on 1 January 2018 with new allocation methods and trading procedures for all market participants (ICAP, 2022). However, it only covers centralised heat and power, extractive industries, and manufacturing or 46% of total GHG emissions (ICAP, 2022). Few transactions have been made under the system due to generous benchmarks, a high number of free quotas, and a low carbon price (IEA, 2022). There are also questions around the reliability of current measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) practices in the trading system (Beisembayev, 2022).

The LTS National Allocation Plan for the period 2022–2025 represents a marginal improvement with an emissions cap of 140.3 MtCO2e for 2022 (ICAP, 2022) and free quotas are expected to be reduced annually by 5.4%, but benchmarking coefficients are expected to remain the same (IEA, 2022; Kumenov, 2021b). Kazakhstan could consider carbon pricing to cover all sectors, enhancing stringency through increasing the carbon price while lowering the emissions cap, and improving the credibility of the system through more predictable planning and more robust MRV.

In its fifth Biennial Report to the UNFCCC (2022), government mentions a carbon tax for sectors not covered by the ETS in its scenario “With Additional Measures” scenario. However, the indicative price level used is rather low: starting at USD 2 per ton of CO2-eq and increasing at USD 2 increments up to 2030 (to USD 16) and at USD 2.5 up to 2035 (to USD 29).

Transport

Transport is responsible for around 8% of Kazakhstan’s total emissions, the bulk of which come from fossil fuel internal combustion engine road vehicles. 85% of the sector’s primary energy needs are met with oil, in contrast to 3% electricity – mostly rail (IEA, 2022). Kazakhstan has introduced some new policies to support the uptake of EVs.

Most recently, the Ministry of Industry and Infrastructure announced that an electric vehicle roadmap had been adopted, setting out regulatory and technical requirements for electric vehicle charging station and promoting domestic production (Kazakhstan to Build More Electric Charging Stations by 2029 - The Astana Times, n.d.). Import taxes were suspended for personal use vehicles (one per person) and all EVs have been exempt from end-of-life recycling taxes since 2021(Roshchanka et al., 2017). However, fossil fuel subsidies and outdated vehicle emission standards will work against such policies without reform.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter