Country summary

Overview

Mexico’s new administration under López Obrador, who took office in December 2018, has not yet developed nor announced the third Especial Programme on Climate Change (PECC 2019-2024) that is required under art. 66 of Mexico’s General Law on Climate Change. This indicates that Mexico has no climate change action plan in place for the short-term, making it even less likely to achieve its international climate goals. In contrast to the previous administrations, López Obrador’s National Development Strategy mentions neither specific climate mitigation goals nor implementation strategies for his administration.

López Obrador’s government has also taken a step backwards on climate by favouring fossil fuels over renewable energy generation. This includes the construction of a new oil refinery and a new budget allocation to the “modernisation” of coal, diesel, gas and oil-fuelled power plants, some of which the previous administration had already scheduled for retirement. After fast tracking permits, the construction of the “Dos Bocas” refinery in Tabasco started in June 2019. The move has come at the expense of a successful renewable energy programme.

The new administration has deprioritised the development of other renewable energy projects by also cancelling Mexico’s 2018 “Long-term electricity auctioning” round. The scheme was introduced in 2015 as one of Mexico’s main instruments to achieve its clean energy targets—of 30% and 35% by 2021 and 2024 respectively—under its Energy Transition Law and General Climate Change Law. These rounds have seen considerable uptake of new renewable energy projects.

The decision to favour fossil fuel generation over renewable energy now puts Mexico on a path that is even more inconsistent with the steps needed to achieve the Paris Agreement's 1.5°C limit. Its plans for the power sector - especially the decision to invest in coal - stands in stark contrast to what is required to achieve the 1.5°C limit. The Paris Agreement means no new coal plants, reducing emissions from the existing coal fleet globally by two-thirds over 2020-2030 and to zero by 2050. The Mexican government’s recent decisions also bring into question whether it will achieve its clean energy targets and its mitigation target spelt out as part of its Paris Agreement commitment.

In October 2019, Mexico published the preliminary rules for its carbon market. The ETS contains a trial phase of 30 months after which the formal start will begin in 2023. The official start was originally scheduled for 2021 but has been delayed multiple times.

The preliminary regulations indicate the emissions cap for the trial phase will be determined by Mexico’s Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT) at least 30 days before its start, based on the reported historical emissions of participants and Mexico’s NDC. Defining the ETS cap on historical emissions puts the programme at risk of not achieving substantial emissions reductions. The cap should instead be set based on ambitious international climate commitments that are in line with the Paris Agreement goal.

*Based on CAT calculations

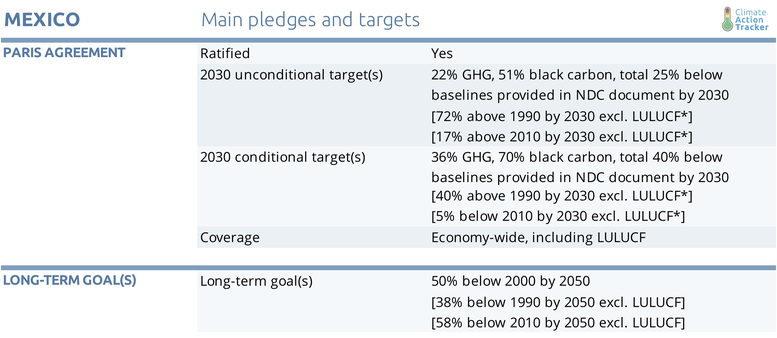

Based on Mexico’s 2030 unconditional target, we rate Mexico “Insufficient.”

According to our analysis, Mexico will need to implement additional policies to reach its proposed NDC targets: Although Mexico has undertaken considerable climate change policy planning and institution building over recent years, the decisions by Mexico’s new administration reverses progress towards implementation of climate change policies.

In April 2012 Mexico adopted its General Climate Change Law (LGCC in Spanish), one of the world’s first climate laws—and the first in a developing country. Under this law, Mexico aims to reduce its emissions by 50% from 2000 levels by 2050. In 2018, this law was reformed to include Mexico’s NDC targets.

Mexico’s LGCC translates the overarching targets into strategies and plans, and provides the institutional framework for its implementation. Part of the institutional framework required by this law includes the development of a National Strategy on Climate Change, providing long-term planning, and a Special Program on Climate Change (PECC) for the short-term planning. Mexico published its first and second National Strategy on Climate Change in 2009 and 2013 respectively, and its first and second PECC in 2008 and 2014 respectively.

Under article 66 of Mexico’s LGCC, every incoming administration is mandated to develop a new PECC reflecting an administrations’ six-year planning on climate change. This document is to include short-term mitigation and adaptation goals per sector, as well as a list of concrete actions, budgeting and clear responsibilities at federal and state level to achieve the goals. This, while aligning the short-term goals with Mexico’s international climate commitments.

Mexico’s current administration, in office since December 2018, has not yet developed nor announced the development of a third PECC for the period PECC 2019-2024. This means that Mexico has currently no short-term action plan for climate change mitigation, making the nation even less likely to achieve its international climate commitments, let alone be aligned with the Paris Agreement goal.

After the COP21 in Paris in 2015, Mexico introduced a major new clean energy policy—its Energy Transition Law, which includes a clean energy target: 25% of electricity generation by 2018, 30% by 2021, and 35% by 2024. The NDC proposal is consistent with these objectives, as is Mexico’s Mid-Century Strategy, which it submitted to the UNFCCC in November 2016.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter