Policies & action

The CAT estimates that Nigeria’s greenhouse gas emissions would reach 62-72% above 2010 levels excluding LULUCF in 2030 under current policies and including the impact of COVID-19.

Nigeria’s current policies are rated 1.5°C compatible when compared to its fair share contribution. The “1.5°C compatible” rating indicates that Nigeria’s climate policies and action are consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C. Nigeria’s climate policies and action do not require other countries to make comparably deeper reductions.

While Nigeria’s policies and action are consistent with a fair contribution to climate action, they do not put Nigeria on track to meet either of its targets. Implementation of the ETP, reflected in our planned policies scenario, would put Nigeria on track to meets its unconditional target, but not its conditional target.

Nigeria will need to implement additional policies with its own resources to meet its unconditional target but will also need international support to implement policies in line with full decarbonisation to meet and exceed its conditional target.

Key steps to reducing the gap between current policies and Nigeria’s NDC targets include progressing towards and ramping up its renewable energy target and halting the expansion of natural gas.

Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against modelled domestic pathways and fair share) can be found here.

Policy overview

Emission levels from current policy trajectory are on course to be between 544-672 MtCO2e in 2035, compared to 430-454 MtCO2e this year 2025. Under current policy projections, emissions are increasing at a rate of about 0.02% per year.

Nigeria's 2021 NDC update includes an unconditional target of between 368-388 MtCO2e by 2030, but the country is not projected to meet this target with current policies. The Long-Term Low-Emissions Development Strategy, published in 2023, sets a net zero target year of 2060 within the framework of the Climate Change Act (National Climate Change Council, 2023a). The plan targets significant long-term action through sectoral targets; however, it relies heavily on action after 2030.

Under the 2021 Climate Change Act, the government is required to develop a carbon tax and carbon trading. In February 2023, the Director General of the National Council on Climate Change announced plans to unveil a carbon tax policy (Gupte, 2023). The policy remains in the planning phase and has not yet been implemented.

The government has recently commenced work on its Second Biennial Transparency Report and Fourth National Communication (BTR2/NC4), raising hopes of further movement on the implementation of climate programs (EnviroNews Nigeria, 2025). New elections for the presidency are not expected before 2027.

The National Climate Change Policy (NCCP) and updated NDC both identify AFOLU as a significant source of emissions. About 70% of these emissions come from burning biomass for energy production, with nearly three quarters of households in 2016 using wood fuels for cooking (Federal Ministry of Environment, 2020). The government's National Gas Expansion Programme aims to convert over 30 million homes from wood fuels to liquified petroleum gas, but no significant developments have been observed yet (Economic Sustainability Committee, 2020).

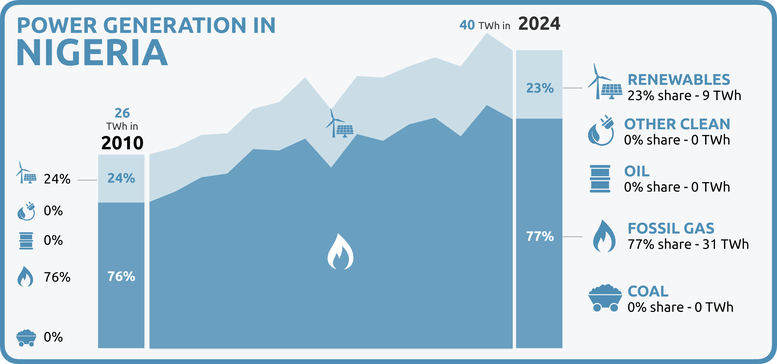

Power sector

In 2024 fossil gas supplied about 80% of electricity generation in Nigeria’s power sector (Ember, 2024). The remaining 20% is supplied by hydropower and negligible shares of solar PV. Coal does not play a role in Nigeria’s electricity supply, and is thus evaluated as "Coal free." While a 600 MW coal-fired plant has been permitted, lack of construction activity and ongoing land-use conflicts make it highly unlikely this plant will ever be constructed or brought online (Global Energy Monitor, 2024).

Nigeria's electricity supply is one of the least reliable in Africa, with the most frequent and prolonged power outages on the continent (IEA, 2019a). These reliability issues contribute to Nigeria's high reliance on expensive oil-fired back-up generators, with households and businesses spending nearly USD 22 billion annually on fuel for generators, or about 5% of 2022 GDP (Dzirutwe, 2022; IMF, 2024). Additionally, Nigeria has the largest population of people without access to electricity, at roughly 88 million in 2023, about 40% of the population (World Bank et al., 2023). The Energy Transition Plan (ETP) identifies the elimination of diesel and petrol generators as the key strategy for the power sector, aiming for universal electricity access by 2030. While the long-term plan targets significant solar PV expansion by 2050, in the short-term the ETP relies on fossil gas as a "transition fuel," risking investment in stranded assets and locking in carbon-intensive infrastructure (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2016).

Fossil gas

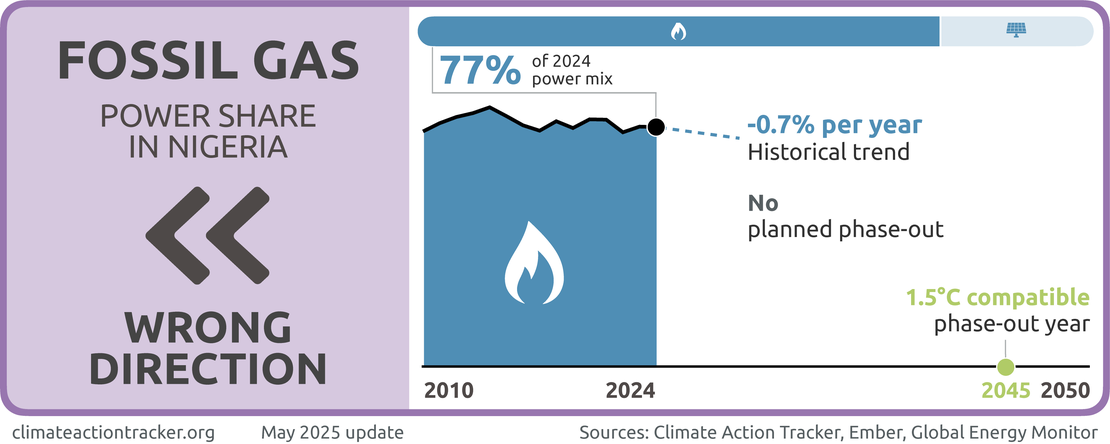

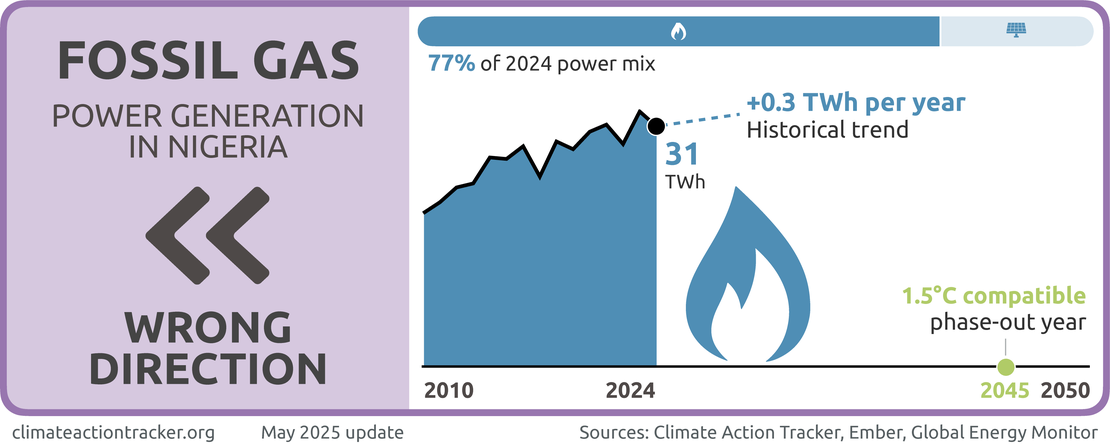

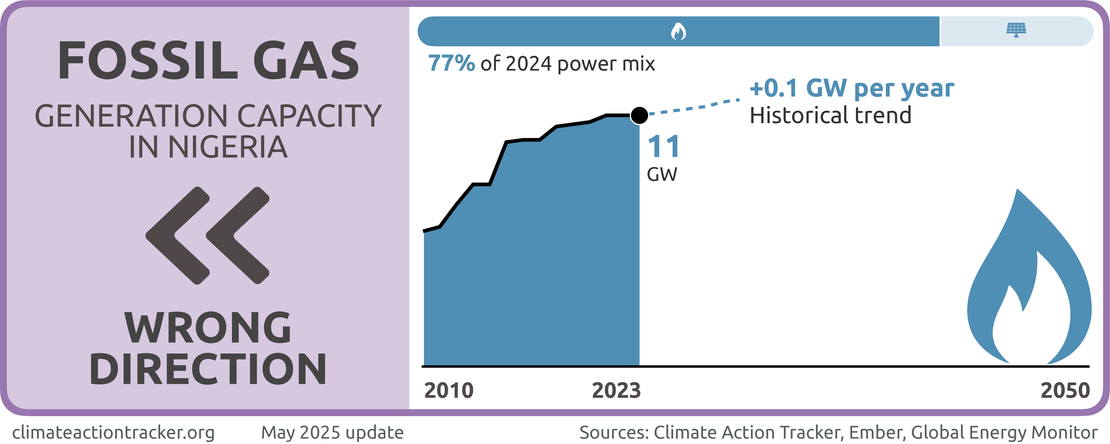

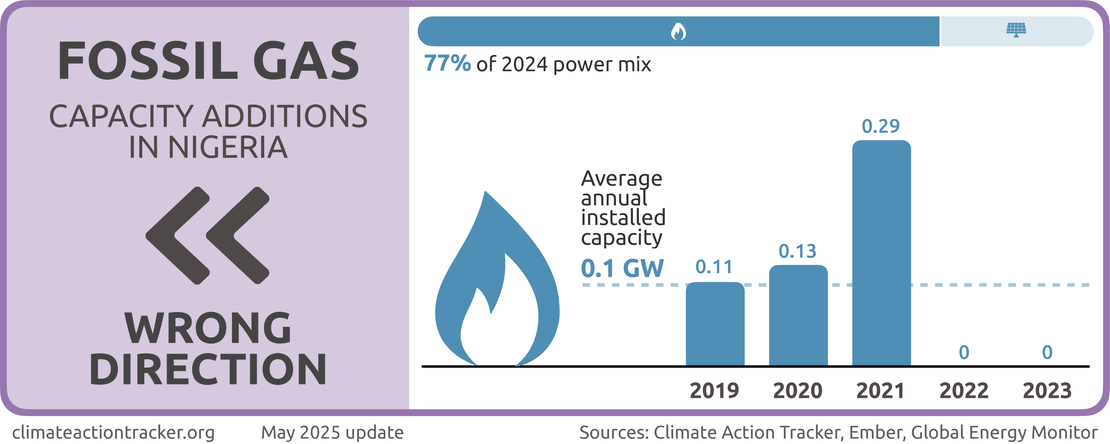

Fossil gas dominates Nigeria's power system, supplying roughly 80% of on-grid electricity generation in 2024 (Ember, 2024). However, due to frequent blackouts, many rely on back-up diesel and petrol generators. With the removal of fuel subsidies (see transport section for more information) and resulting high cost of petrol, Nigerians are seeking cheaper alternatives including solar PV and converting their generators to run on gas (Adebayo, 2023; Olawin, 2023). Fossil gas generation in Nigeria has remained largely stagnant over the last five years, while its share in the overall power mix has been decreasing. However, significant planned capacity additions are pushing fossil gas generation in Nigeria in the "Wrong direction."

Nigeria does not have a comprehensive fossil gas phase-out target for power generation. The Energy Transition Plan presents a mixed approach: it targets a reduction in oil and gas generation from "decentralised" generators from 5.3 GW in 2020 to 3.2 GW in 2030, with a full phase-out by 2050. However, for centralised power generation, the ETP positions fossil gas as a "transition fuel" with plans to expand fossil gas generation. Specifically, the ETP expects to ramp up available centralised gas capacity from 4 GW in 2020 to 14 GW by 2030 and anticipates 10 GW of gas capacity remaining in the power mix by mid-century.

This approach is not aligned with the Paris Agreement goal to limit global warming to 1.5°C. The CAT’s 1.5°C compatible benchmarks see Nigeria phasing down gas to between 1-15% share of power generation by 2040 and completely phased out by 2045 (NewClimate Institute and Climate Analytics, 2024). Relying on fossil gas runs the risk of investing in stranded assets as future gas demand is subject to large uncertainties.

Recent developments include the commencement of construction on the 1.3 GW Gwagwalada Independent fossil gas power plant in 2023. However, Nigeria's high reliance on fossil gas for power has contributed to the instability of the grid. In addition to poor infrastructure, gas supply disruptions from vandalism or financial trouble cause blackouts and reduce power generation (NewsDirect, 2024; Okechukwu Nnodim, 2024; Wiliams et al., 2024).

Nigeria's Long-Term Low-Emission Development Strategy (LT-LEDS) introduces strategies to reduce power sector emissions and emphasises uptake of combined cycle gas plants with carbon capture and storage (CCS) and the acceleration of CCS integration and standardisation for widespread implementation across the power and oil & gas sectors. Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) refers to technologies which use engineered methods to capture CO2 from a source and store it geologically; however, these technologies are neither commercially viable nor proven at scale, despite large public subsidies for research and development globally. Heavily relying on unproven CCS for power generation simply prolongs the use of fossil fuels, diverting attention and resources away from the necessary and urgent switch to renewable energy generation that drives down actual emissions.

Renewables

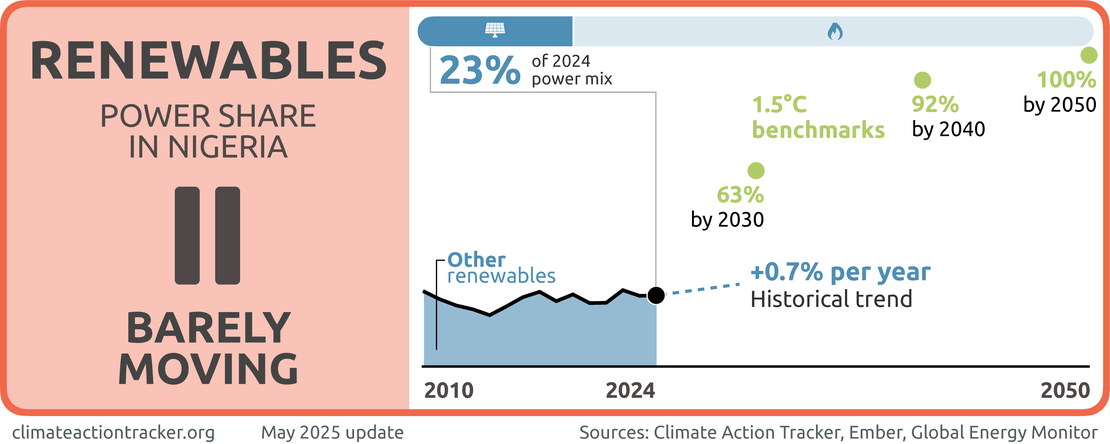

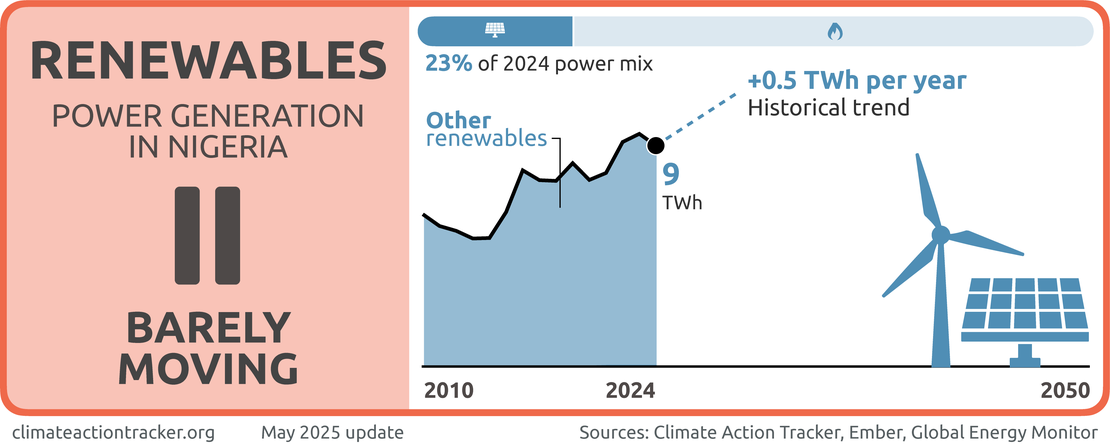

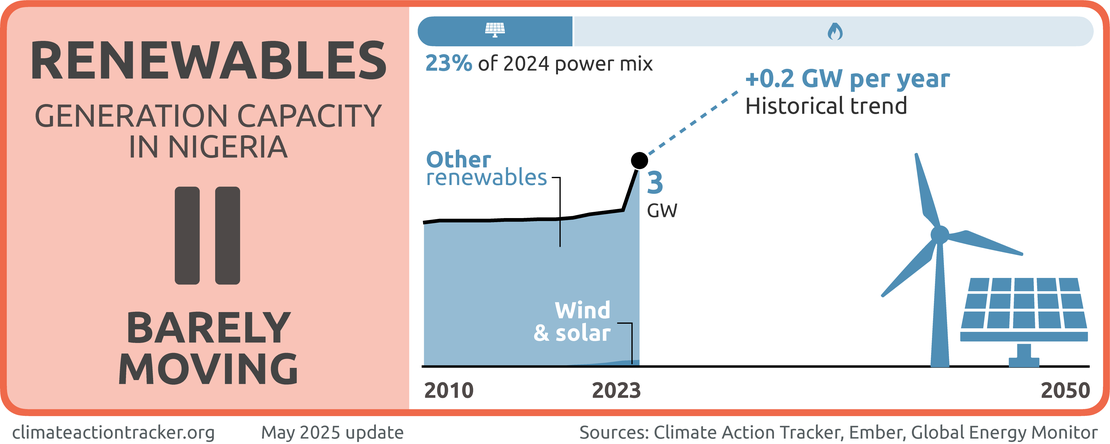

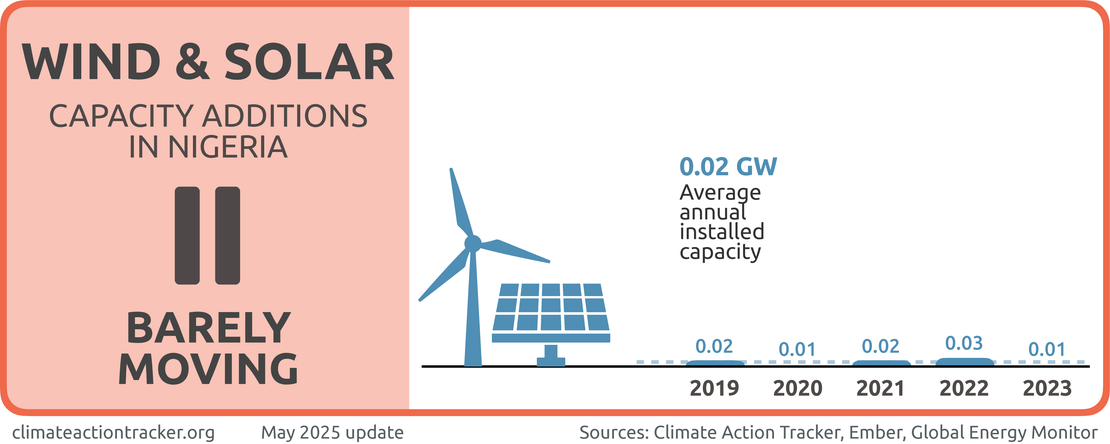

Renewable energy generation in Nigeria has shown minimal growth over the last five years, with essentially no growth in wind and solar and other renewables (primarily hydropower) increasing minimally. The share of renewables in the overall power mix has also barely changed over the last five years. Nigeria's target of over 23 GW of renewable capacity by 2030, outlined in the 2015 NREEEP, is ambitious but implementation has been extremely slow, with only 21 MW of renewable capacity added between 2015 and 2022. The Energy Transition Plan sets longer-term targets of nearly 200 GW of solar PV by 2050 but lacks concrete near-term implementation measures. We evaluate progress in this sector as "Barely moving."

The Economic Sustainability Plan includes measures to install solar power in five million homes by 2023, though there is little information on progress towards this target. Initial funding was announced in 2021, and in March 2023, the Rural Electrification Agency was working to attract further investment to connect underserved areas to the grid (Akande, 2022; Shetty, 2023).

To be 1.5°C compatible, CAT benchmarks see the share of renewables in Nigeria’s power mix increasing to 55-71% by 2030 and continuing on a steep incline to 85-99% by 2040 (NewClimate Institute and Climate Analytics, 2024). Nigeria will need significant international support to achieve a transition at this scale.

CAT analysis shows that shifting to renewables would not only put Nigeria on a 1.5°C compatible pathway, but would also create more jobs than its current gas-based strategy. Nigeria's Long-Term Low-Emission Development Strategy introduces scenarios for renewable energy development, with the Renewable Energy Scenario being the only one that achieves Nigeria's 2060 net zero goal. However, these scenarios are largely illustrative and lack concrete implementation plans.

Industry

Oil & gas production

Nigeria, a member of OPEC, was the 15th largest oil producer in the world in 2023 (US EIA, 2024). Nigeria is also the 19th largest natural gas producer in the world and plans to increase current production threefold (IEA, 2021a; The Guardian, 2021). The country’s economy is highly dependent on its oil and gas sector, accounting for about 40% of government revenue in 2021 (Central Bank of Nigeria, 2021). Despite the recovery of oil prices, this share is down from about 54% of government revenue in 2019, largely due to low oil and gas production.

Crude oil theft and pipeline vandalism has surged in recent years, impacting oil and gas production and government revenues (Central Bank of Nigeria, 2021). In October 2023, crude oil production reached 1.35 million barrels per day (bpd) against a benchmark of 1.69 million bpd. National Security Adviser Nihu Ribadu stated that as of 2023 Nigeria loses up to 400,000 barrels of crude oil per day to theft (Ships & Ports, 2023). The Nigerian government has engaged the military to support monitoring and operations to crack down on systematic and widespread theft and illegal refining (Omeje, 2024).

These issues of theft and vandalism, among other reasons such as militant activity, have led international oil companies (IOCs) to divest from their assets in Nigeria, largely selling to domestic Nigerian firms (Stakeholder Democracy Network, 2021). Reports have indicated that divestments of IOCs to domestic companies have exacerbated pollution and increased flaring in the Delta (Chason, 2023). This raised concerns over how to hold IOCs accountable for the oil spills after they exit the region (Stakeholder Democracy Network, 2021).

While IOCs have been divesting in assets since the early 2010s, there has been a renewed surge of sales in recent years (Stakeholder Democracy Network, 2021). In 2021, Shell announced its intent to sell its stake in onshore oilfields. However, in October 2024, Nigeria’s oil regulator rejected the sale as the buyer was determined unfit to manage the assets (Bousso, 2022b, 2022a; Reuters, 2024). Nigerian communities and organisations also opposed the sale until Shell is held accountable for environmental damages (Ajala, 2024; Shell, 2024). Other IOCs including French TotalEnergies and Italian firm Eni have sold onshore assets, with ExxonMobil also attempting to sell all shallow water assets in Nigeria (Egbejule, 2022; Onsat, 2024; Stakeholder Democracy Network, 2021).

Despite supply challenges, European interest in importing natural gas from Africa surged amid the global energy crisis (Aljazeera, 2022). This has spurred renewed interest in export infrastructure projects even though new export infrastructure would not be operational in time to counter the short-term impacts of the crisis (Rahhou, 2022).

The conflict between Algeria and Morocco has also led both countries to push ahead with competing gas pipelines that would connect Nigeria to Europe: the Nigeria-Morocco pipeline and the Trans-Saharan pipeline that passes through Algeria (France 24, 2023).

Despite the significant challenges and costs faced by the Trans-Saharan pipeline, Nigeria continues to push new pipeline projects, with President Tinubu signing a gas pipeline project agreement with Equatorial Guinea in August of 2024 (Onuah, 2024; Sofiullahi, 2024).

This rise in the use of fossil gas in Africa, and globally, is not aligned with the Paris Agreement goal to limit global warming to 1.5°C. Relying on fossil gas runs the risk of investing in stranded assets, as future gas demand is subject to large uncertainties. CAT analysis shows that shifting to renewables would not only put Nigeria on a 1.5°C compatible pathway, but would also create more jobs than its current gas-based strategy.

Nigeria’s COVID-19 stimulus plan, the Economic Sustainability Plan (ESP), includes a domestic gas utilisation programme aimed at reducing the country’s reliance on oil (Economic Sustinability Committee, 2020). This includes the promotion of compressed natural gas (CNG) for use in the transport sector. In May 2024, state oil firm NNPC announced it was commissioning six CNG stations, with the first in Lagos expected to have a capacity of up to 5.2 million standard cubic feet of CNG per day (Eboh, 2024).

In August 2021, former President Buhari signed the Petroleum Industry Bill (PIB) into law to improve transparency and accountability in the oil sector and ultimately attract more international investment in the sector (Esiedesa, 2021; Thomas, 2020). This comes after 20 years of attempts to pass the bill, which has received criticism for potential environmental and social impacts (Ene, 2018; EnviroNews Nigeria, 2021; Iroanusi, 2021; KPMG in Nigeria, 2021). However, increased expansion of oil infrastructure and production increases the risk of costly stranded assets as countries and private sector actors divest from fossil fuels (CCAC Secretariat, 2023).

Gas flaring

In 2000, Nigeria was flaring roughly 55% of the gas it was extracting. To reduce emissions from gas flaring, Nigeria set the goal of eliminating routine flaring by 2020, a decade ahead of the World Bank’s “Zero Routine Flaring by 2030” initiative. In 2018, Nigeria further adopted a gas flare commercialisation programme based on the “polluter pays” principle (Ogunleye, Banks, and Legarreta 2019). While Nigeria did not meet its 2020 target, it has made significant progress, now flaring only 10% of extracted gas. The ETP targets zero flaring by 2030, as well as a 95% reduction of fugitive emissions from oil and gas by 2050 (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2022).

Transport

The Nigerian government has made repeated attempts to remove subsidies for premium motor spirit fuels (petrol), as it accounts for a significant portion of the government’s budget. In response to COVID-19, Nigeria announced the removal of petrol subsidies in 2020, but this was not achieved (Official Gazette, 2020). Uncertainty and confusion over government pricing-induced fuel shortages, likely due to a price hike by depot owners in anticipation of higher prices as international oil prices rebound (Olawoyin, 2021). Nigeria had announced a similar removal of subsidies in 2016 after a fall in oil prices but returned to subsidising petrol in 2017 when crude prices rebounded.

In 2023, President Tinubu announced the removal of petrol subsidies, with fixed prices for different regions as a key part of his policy platform (Brnic & McColloch, 2023).

Petrol prices have now essentially doubled across Nigeria, contributing significantly to the cost-of-living crisis. Facing significant public pushback and street protests, President Tinubu partially reinstated the subsidy from February 2024 by capping fuel prices, as confirmed by the IMF[MOU4] (Norways & Tracey-Cook, 2024). However, the official position of the Tinubu administration is that the subsidy has not be reinstated, even as President Tinubu approved the transfer of roughly USD 1.3bn in revenues back to NNPC to partially cover the USD 4.9bn subsidy debt NNPC says it is owed for the first two quarters of 2024 (Adeuyi, 2024; Agbetiloye, 2024).

Fuel subsidies represent a significant strain on limited government resources and support the continued use of fossil fuels; however, the impact of removing these subsidies, particularly on vulnerable groups, needs to be mitigated to ensure a just transition. Shifting to electric vehicles (EVs) and expanding public transport systems can reduce demand for petrol and limit the need for subsidies.

The Energy Transition Plan (ETP) sets the target to achieve 100% EVs by 2060, but progress towards this goal is largely expected to happen after 2030 (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2022). The ETP targets increased biofuel blend rates of 10% by 2030 and 30% by 2036.

Nigeria’s COVID-19 stimulus plan, the Economic Sustainability Plan (ESP), includes a domestic gas utilisation programme aimed at reducing the country’s reliance on oil (Economic Sustinability Committee, 2020). This includes the promotion of compressed natural gas (CNG) for use in the transport sector. However, CNG is not mentioned in the ETP transport strategy.

Nigeria’s National Action Plan to Reduce Short-lived Pollutants includes measures to limit emissions from the transport sector (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2019). It includes measures to eliminate the use of high-emitting vehicles, including a ban on vehicle imports more than 15 years old (implemented) and increasingly stringent emission standards (Euro III by 2023, Euro IV by 2030). The plan also aims to renew the urban bus fleet in Lagos and adopt CNG buses across Nigeria, introduce low sulphur diesel and petrol, and promote a shift from road to rail and water transport. (Adeuyi, 2024; Agbetiloye, 2024; Brnic & McColloch, 2023; Norways & Tracey-Cook, 2024; Official Gazette, 2020; Olawoyin, 2021).

There is significant uncertainty around land use and forestry emissions estimates in Nigeria. The country’s Third National Communication (TNC) estimates LULUCF contributes to roughly half of Nigeria’s emissions (over 300 MtCO2e in 2016), while the NDC update reports land use emissions together with agriculture as about one quarter of emissions (approximately 87 MtCO2e in 2018). More recently, the LT-LEDS shows the 2018 share of land use and agricultural emissions at 30%, or 126 MtCO2e (Federal Ministry of Environment, 2020, 2021b; National Climate Change Council, 2023a).

Traditional biomass is Nigeria’s largest source of primary energy. In 2016, almost three quarters of households used fuelwood for cooking (Federal Ministry of Environment, 2020). Nigeria’s National Gas Expansion Programme, part of the Economic Sustainability Plan in response to COVID-19, aims to convert over 30 million homes from traditional fuels such as wood and kerosene to liquified petroleum gas to reduce emissions (Economic Sustinability Committee, 2020).

Nigeria’s TNC estimated CO₂ emissions from biomass consumption for energy production were about 70% of agriculture, forestry and other land use emissions (42% of total emissions) (Federal Ministry of Environment, 2020). The use of traditional biomass for cooking is linked to indoor air pollution and associated health risks as well as gender labour inequities (Addo & Olajide, 2021; Uchenna & Oluwabunmi, 2020).

In 2020, a new National Forest Policy was approved by the Federal Executive Council that is expected to boost climate efforts in the country, but the policy is not available online. As summarised in the LT-LEDS, the policy includes a target to increase forest cover from the current 6% to 25% by 2030 (National Climate Change Council, 2023a).

From 2001 to 2016, Nigeria’s tree cover decreased by 9.4%, largely due to shifting agricultural lands (Global Forest Watch, 2021). In July 2021, Nigeria launched its National Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD+) Strategy with the aim of reducing forest sector emissions by 20% by 2050 (Federal Ministry of Environment, 2021a; Olugbode, 2021). Pilot REDD+ activities have already progressed in Cross River State, home to half of Nigeria’s forests (FME & UNDP, 2019). Cross River State has developed its own REDD+ strategy and approach to safeguards and submitted its forest reference emission level to the UNFCCC.

Nigeria is a member state of the Great Green Wall (GGW) initiative. The initiative, launched in 2007 by the African Union, aims to restore degraded land, sequester carbon and create green jobs across in the Sahel region. A key goal of Nigeria’s GGW programme is the establishment of a 1,359 km contiguous shelterbelt to serve as windbreaks from Kebbi State in the northwest to Borno State in the northeast (UNCCD, n.d.). From 2007 to 2020, the programme established 709 km of windbreaks and created 2,801 hectares of reforested land and 1,396 jobs (Climatekos gGmbH & UNCCD, 2020; UNCCD, 2023).

Methane

Nigeria is a signatory to the Global Methane Pledge, and in 2023 joined the Global Methane Pledge Champions alongside the EU, United states, Japan, Germany, Federated States of Micronesia and Canada (Climate & Clean Air Coalition, 2023).

In 2023, Nigeria produced roughly 139 MtCO2e of methane emissions (Gütschow et al., 2024). Fugitive methane from the energy sector accounted for about 13% of Nigeria’s emissions (excl. LULUCF) in the same year. Nigeria’s 2021 NDC Update and LT-LEDS focus on reducing fugitive methane emissions and leaks in the oil and gas sector, targeting a 60% reduction by 2031. Within the Agricultural sector, the second largest source of methane emissions, Nigeria’s LT-LEDS focuses on strategies to reduce enteric fermentation and improve livestock waste management without specifically mentioning methane emissions or setting a methane emissions reduction target.

In 2023, Nigeria put forward new Methane Guidelines for the oil and gas sector to help reduce fugitive emissions. The guidelines mandate measures such as leak detection, repairs and high destruction efficiency flares. According to the Climate and Clean Air Coalition (CCAC) that provided support developing the guidelines, support will be needed to ensure implementation and enforcement (CCAC Secretariat, 2023).

CCAC and the Nigerian government continue to cooperate on stakeholder engagement and education activities to support the implementation of the guidelines, including hosting trainings on leak detection and repair and the use of online tools to estimate methane emissions (Aminu, 2024; Emeh, 2024).

Additionally, Nigeria’s National Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency (NOSDRA) is currently in the process of developing a Satellite-based Methane Emission Tracker (SMET) to support data-gathering, benchmarking efforts, and identification of leaks and fugitive methane emissions across Nigeria (Mahmoud, 2024).

Further analysis

Country-related publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter