Policies & action

The EU’s emissions have decreased in recent years, with an accelerating trend since 2017 and a major dip in emissions in 2020 as a result of the impacts of COVID-19. However, emissions have increased by 5% in 2021 due to the economic rebound. It remains to be seen whether the policies introduced in the EU in reaction to the ongoing energy crisis will be sufficient to instigate a transformative change necessary for 1.5°C-compatibility or whether the EU and its member states replace dependency on energy imports from Russia with fossil fuel imports from other countries.

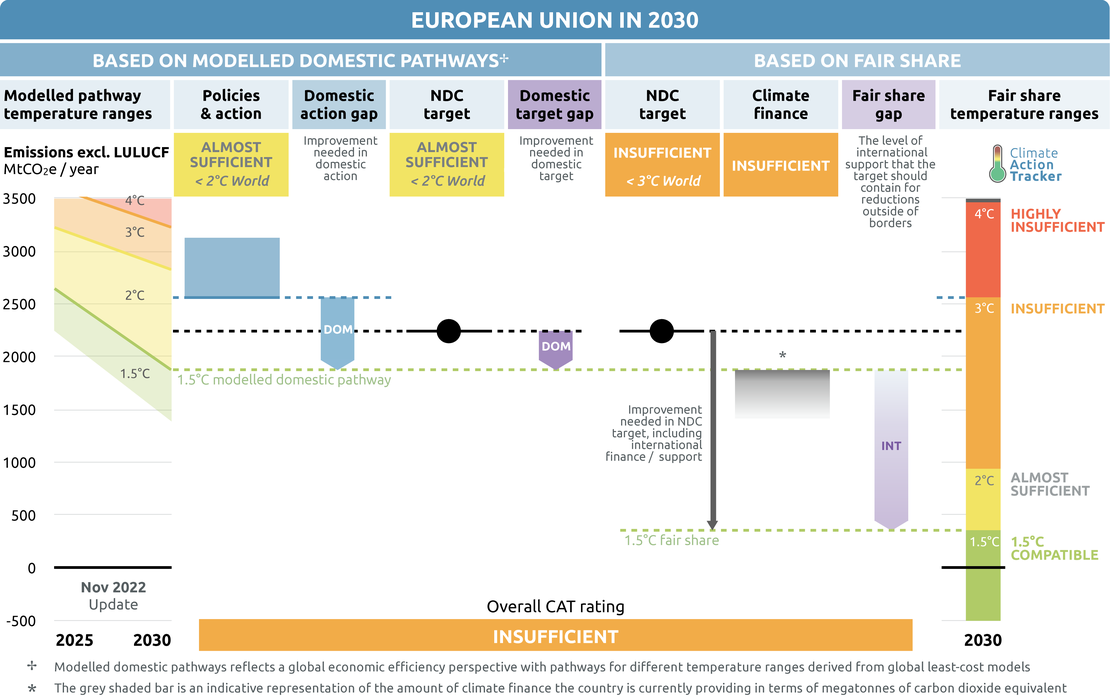

While the proposals presented by the European Commission in July 2021 would result in emissions reductions of around 54% below 1990 levels, policies implemented to date would only result in emissions reductions between 36-47%. This difference is the result of national policies lagging behind policies adopted at the EU level. We consider the lower emissions bound to be more likely and have based the CAT range on this estimate. The CAT rates the EU’s policies and action as “Almost sufficient”.

The “Almost sufficient” rating indicates that the EU’s climate policies and action in 2030 are not yet consistent with the 1.5°C temperature limit but could be, with moderate improvements. If all countries were to follow the EU’s approach, warming could be held below—but not well below—2°C.

Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against modelled pathways and fair share) can be found here.

Policy overview

After a pandemic-driven decrease by over 8% in 2020, emissions in the EU (incl. LULUCF) increased by 5% in 2021 (European Environment Agency, 2022c). The policies implemented and reported to the European Commission by March 2021 would result in emissions of around 3.1 GtCO2e by 2030. This would mean an emissions reduction of 35% below 2005 levels, or only slightly below 2020 levels. Policies adopted at the EU level but not yet fully implemented by the member states would result in emission reductions of 47% below 1990. Both scenarios are far off the recently adopted emissions reduction goal of “at least 55%” (including LULUCF), or 53.9% excluding LULUCF and intra-EU aviation and maritime transport.

“Fit for 55” package and REPowerEU Plan

To close the gap between the EU’s climate target and its policies, the European Commission presented its “Fit for 55” policy package to achieve this goal in July 2021 (European Commission, 2021d).

The package includes 12 pieces of legislation, complemented with the draft of the Energy Performance in Buildings Directive published in December 2021. Some of these proposals were strengthened in the framework of the May 2022 European Commission REPowerEU Plan, formed in reaction to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the ensuing energy crisis (European Commission, 2022m). Should these goals be implemented and achieved, this would result in emissions decreasing by between 58-60% (incl. LULUCF) in 2030 in comparison to 1990.

Below changes to the proposals covering more than one sector are shortly explained. Proposals focusing on development of renewables, transport, LULUCF, and buildings sectors are described in the respective sections.

EU ETS

The reform of the EU ETS should accelerate emissions reductions in the sectors covered, especially the electricity and industry sectors. The negotiations between the European Parliament and the Council are set to take place in late 2022.

The proposal tabled by the European Commission in July 2021 as part of the “Fit for 55” package suggested increasing the 43% emissions reduction goal for the sectors covered by the EU ETS – especially electricity generation and industry - between 2005 and 2030 to 61% (European Commission, 2021g). In May 2022 the Environmental Committee of the European Parliament (ENVI Committee) approved an amendment that would result in a 2030 emissions reduction goal for the EU ETS sectors of 67% below 2005 levels (Committee on Environment Food Safety and Public Health., 2022).

The final version approved by the plenary of the European Parliament was weakened to 63%, with the cap decrease accelerating in the second half of the 2020s, resulting in only small improvements compared with the Commission’s proposal (European Parliament, 2022d). In its negotiating position the Council proposed an emissions reduction in the EU ETS of 61%, the same as indicated by the European Commission in its proposal from July 2021 (Council of the European Union, 2022f). In the coming months both institutions will try to reach a compromise on emissions reduction in the sectors covered by the EU ETS.

Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR)

The higher, “at least 55%” emissions reduction goal also requires increased emissions reduction goals in sectors not covered by the EU ETS, especially the transport and buildings sectors, which are covered by the Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR). Adopted in 2018, this law translated the 30% emissions reduction goal in non-EU ETS sectors into national targets based on the member states’ respective socioeconomic circumstances. The targets were ranging between 0% (Bulgaria) to 40% (Luxembourg) below 2005 levels (European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, 2018b).

In its “Fit for 55” package, the Commission proposed increasing the emissions reduction goal in the ESR sectors by 40% on average, with national emissions reduction goals ranging between 10% and 50% below 2005 levels by 2030 (European Commission, 2021j). Negotiations between the EU institutions started in September 2022.

Renewable Energy Directive

The “Fit for 55” package also includes proposals for a higher share of renewables in 2030. According to the proposal for the amendment of the Renewable Energy Directive, the target for the share of renewables in energy consumption is to increase from 32% to 40% (European Commission, 2021f).

After Russia illegally invaded Ukraine, the European Parliament’s Rapporteur for the amendment of the Renewable Energy Directive suggested increasing this goal to 45%, with the Green faction calling for a 50% renewable energy goal (EPP Group, 2022; The Greens - European Free Alliance, 2022). In May 2022 the European Commission presented its REPowerEU Plan which proposed increasing the share of renewables in final energy consumption to 45% (European Commission, 2022e).

The Council of Ministers took the earlier goal of increasing the share of renewables in the energy mix to only 40% as its starting position, in September the European Parliament adopted the 45% target (Council of the European Union, 2022d; European Parliament, 2022a). Negotiations between the EU institutions started in October 2022 and are ongoing.

Energy Efficiency Directive

The European Commission’s July 2021 package of proposals also included higher energy efficiency goals. According to the recast of the Energy Efficiency Directive, by 2030 EU member states should reduce their total primary energy consumption to no more than 1,023 Mtoe. Their final energy consumption should not exceed 787 Mtoe (European Commission, 2021h).

The Commission’s REPowerEU Plan from May 2022 included the goal of decreasing EU’s primary energy consumption to 980 Mtoe and final energy consumption to 750 Mtoe by 2030 (European Commission, 2022e). Whereas the Council of Ministers ignored the Commission’s REPowerEU Plan in its negotiating position, the European Parliament adopted a more ambitious approach than the Commission and suggested reducing primary energy consumption to no more than 960 Mtoe and final energy consumption to 740 Mtoe. The negotiations between the EU institutions are set to end in 2022 or in early 2023.

| Status in 2020 | Currently binding for 2030 | Proposed in 'Fit for 55' Package from July 2021 | Proposed in REPowerEU Plan from May 2022 | Position of the European Parliament | Position of the Council of Ministers |

|---|

| Share of renewables in 2030 | 22% | 32% | 40% | 45% | 45% | 40% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary energy consumption in Mtoe | 1,379 | 1,273 | 1,023 | 980 | 960 | 1,023 |

| Final energy consumption in Mtoe | 907 | 956 | 787 | 750 | 740 | 787 |

Based on (Council of the European Union, 2022i; European Parliament, 2022c; European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, 2018a; Eurostat, 2022d, 2022e).

Emergency measures

The significant increase in energy prices driven by Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine is a significant challenge to the European citizens and economy. To mitigate this challenge, the EU and its member states have adopted measures aiming at reducing energy costs and consumption.

In July 2022, EU member states agreed to reduce their fossil gas consumption by 15% between August 2022 and March 2023. However, it includes numerous derogations from meeting this voluntary target, which reduce its impact (Council of the European Union, 2022g). Many member states adopted measures aimed at reducing energy consumption, such as curbing air conditioning in summer and heating of public buildings in winter, ensuring that doors of heated or cooled shops remain closed, and switching off advertisements after 10 p.m. (Politico, 2022).

In September 2022, member states agreed to the voluntary target of reducing 10% of their gross electricity consumption and mandatory target of 5% electricity consumption in peak hours between December 2022 and March 2023 (Council of the European Union, 2022a). Finally, a number of countries adopted measures that compensate consumers for higher energy costs or reduced energy taxes (Bruegel, 2022d).

While justified by the extraordinary situation, many of these measures, especially a reduction in taxes or even direct price subsidies, reduce the incentive to decrease the consumption of fossil fuels and move towards low carbon alternatives. A war-like effort to accelerate the development of renewables, manufacture and deploy heat pumps, and facilitate energy efficiency measures to achieve energy savings, would result in a lasting decrease in the consumption of fossil fuels, and with them, cost reductions. While some countries have improved the investment conditions for renewables, such incremental changes do not reflect the urgency of the situation created by the energy and climate crises.

The EU itself failed to mobilise any additional meaningful sources of funding. In its REPowerEU Plan the Commission suggested modifying member states' Resilience and Recovery Plans that form the basis of resource distribution in the framework of the post-pandemic Recovery Fund, by adding REPowerEU chapters. However, the only new revenue in the EUR 20 bn would come from the sale of emissions allowances from the Market Stability Reserve (MSR) (European Commission, 2022f). This would reduce the price of emissions allowances, reducing the overall proceeds from the sale of these allowances which should be invested in emissions reduction anyway.

Sectoral pledges

In Glasgow, a number of sectoral initiatives were launched to accelerate climate action on methane, the coal exit, 100% EVs and forests. At most, these initiatives may close the 2030 emissions gap by around 9% - or 2.2 GtCO2e, though assessing what is new and what is already covered by existing NDC targets is challenging.

For methane, signatories agreed to cut emissions in all sectors by 30% globally over the next decade (Climate and Clean Air Coalition Secretariat, 2021). The coal exit initiative seeks to transition away from unabated coal power by the 2030s or 2040s and to cease building new coal plants (UN Climate Change Conference (COP26), 2021). Signatories of the 100% EVs declaration agreed that 100% of new car and van sales in 2040 should be electric vehicles, 2035 for leading markets (UK Government/UNFCCC, 2021a), and on forests, leaders agreed “to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030” (UK Government/UNFCCC, 2021b). The Beyond Oil & Gas Alliance (BOGA) seeks to facilitate a managed phase out of oil and gas production.

NDCs should be updated to include these sectoral initiatives, if they aren’t already covered by existing NDC targets. As with all targets, implementation of the necessary policies and measures is critical to ensuring that these sectoral objectives are actually achieved.

| EU | Signed? | Included in NDC? | Taking action to achieve? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methane | Yes | No | Yes |

| Coal Exit | Yes | No | Yes |

| Electric vehicles | 14 EU member states | No | Yes |

| Forestry | Yes | No | Neutral |

| Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance | 8 EU member states | No | No |

- Methane pledge: The EU signed the methane pledge at COP26. In 2020 the European Commission published a strategy to reduce methane emissions, which listed a number of measures that should be implemented to achieve this goal. In December 2021, the Commission tabled a proposal of a directive that strengthened reporting and monitoring requirements and introduced mandatory leak detection and repair, and a ban on gas flaring and venting (European Commission, 2020i, 2021o).

- Coal exit: The EU signed up to the coal pledge at COP26. While a large majority of the EU member states either don’t use coal or have an exit date before 2030, Poland, the second largest coal consumer in the EU, failed to move its coal extraction phase-out date forward from 2049. At the same time, EU’s REPowerEU Plan includes EUR 2 bn to adapt coal power plants in the EU to operate longer and shift from gas to coal. This undermines EU’s climate ambition.

- 100% EVs: The EU did not sign the 100% zero emission cars and vans Glasgow pledge. However, 14 EU member states did so. In the framework of the European Green Deal the EU is discussing phasing out the sale of combustion vehicles by 2035.

- Forestry: The EU signed the forestry pledge at COP26 in Glasgow. In July 2021, European Commission proposed an amendment of the EU’s LULUCF Directive that would de facto create a separate target for the LULUCF sink of 85 MtCO2e, in addition to 225 MtCO2eq, which is the maximum that can be included in the EU emissions reduction goal.

- Beyond oil & gas: The EU has not signed the Beyond Oil and Gas (BOGA) declaration but eight of its member states have. Four member states—Denmark, France, Ireland and Sweden—are core members of the alliance and have committed to ending oil and gas exploration and development.

Energy supply

After falling by 4% in 2020, electricity consumption in 2021 increased by 5% and returned to 2019 levels. This contributed to an increase in emissions from electricity generation: after falling by 14% in 2020, emissions increased by 9% in 2021. Contrary to electricity consumption, which returned to the same level as in the last pre-pandemic year, emissions from the sector were 6% below 2019 levels, indicating lower emissions intensity (European Commission, 2021r, 2022g). Emissions intensity of electricity fell from 253 gCO2eq/kWh in 2020 to 241 gCO2eq/kWh in 2021 (a 4.7% decrease) (Ember Climate, 2022b).

In the first and second quarters of 2022, electricity consumption and emissions were heavily influenced by the significant increase in electricity prices: the average wholesale electricity price in the EU reached EUR 201/MWh in the first quarter and fell only slightly to EUR 191/MWh in the second quarter (European Commission, 2022h, 2022i). Electricity consumption decreased by 1% and 0.4% respectively in comparison to quarter one and two of 2021. The unplanned outages of nuclear power plants in France added pressure on the electricity market, resulting in increased generation from fossil fuel power plants.

In the context of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the resulting volatility in commodity markets, prices have remained high. At the same time, there are some indications of a significant acceleration in renewable energy development and stabilisation of fossil gas prices.

Electricity emissions intensity

According to a recently-published study (Ember Climate, 2022d), the EU could fully decarbonise its electricity sector by 2035. While it would require additional upfront investment of between EUR 300–750 bn, it would result in savings of around EUR 1 tn by 2035. This would be in addition to significant benefits in emissions reductions, health, and reducing EU fossil fuel dependency. According to the scenario, by 2030, between 70–80% of electricity would be coming from wind and solar PV, with the share of coal and fossil gas decreasing to less than 1% and 5%, respectively.

Renewables

In 2021, an additional 37 GW of solar and wind energy capacity were added to the grid, compared to 29 GW in 2020. Despite a decrease in onshore wind generation, generation from renewables in absolute terms was 90 TWh higher than in 2020 and amounted to 1,030 TWh. However, due to increased total electricity generation, the share of renewables decreased by 1 percentage point to reach 38% (European Commission, 2022g).

The share of renewables increased from 39% in Q1 to 43% in Q2 2022: 2 and 1 percentage point higher than in the corresponding periods of 2021 (European Commission, 2021r, 2022g). The significant increase in onshore and offshore wind, as well as solar (by 20%, 8%, and 31%, respectively), especially in the second quarter, was counterbalanced by a 27% decrease in generation from hydro power plants driven by drought. In the background of the ongoing energy crisis, many member states increased their renewable electricity goals, with Portugal, the Netherlands, Denmark, and Austria aiming for a fully decarbonised electricity sector by 2030. Except for the Netherlands, this goal is to be achieved exclusively with renewables (Euronews, 2022b).

Wind

Newly installed wind capacity in the EU in 2021 remained at a low level, around 11 GW, almost 90% of which was onshore (WindEurope, 2022d). By the end of 2021, there EU’s combined installed wind energy capacity amounted to 189 GW. WindEurope expects an acceleration in wind energy development, with projected average annual installations of 18 GW between 2022–2026.

However, to meet the goal of 510 GW installed wind energy capacity proposed by the Commission in its REPowerEU Plan, at least 40 GW would have to be installed annually—three times the capacity installed in 2020 and 2021. On a positive note, investments in new onshore wind farms increased from around EUR 19 bn in 2020 to almost EUR 25 bn in 2021, the highest level since 2016. This indicates an increase in the pipeline of new projects (WindEurope, 2022b).

At the same time, contrary to some countries’ plans to increase the role of offshore wind in their future energy mix, investment in offshore wind fell from almost EUR 28 bn in 2020 to less than EUR 17 bn in 2021 (WindEurope, 2022b). Less than 1 GW of new offshore wind capacity went online, and only in Denmark and the Netherlands (WindEurope, 2022d). Only 30 MW of offshore wind were added to the grid in the first half of 2022 in Italy, but work on four other projects in Germany (342 MW), the Netherlands (two projects with combined capacity of 1,520 MW), and France (480 MW) continued (WindEurope, 2022c).

According to the European Commission, between 240 to 450 GW of installed capacity in offshore wind will be needed to reach the 2050 emissions neutrality goal (European Commission, 2020j). The commitments of EU member states, if met, would allow the EU to reach the lower end of this range.

At the end of August 2022, leaders of eight countries around the Baltic Sea committed to increasing the capacity of offshore wind in this area from less than 3 GW currently to almost 20 GW by 2030 (WindEurope, 2022a).

Two weeks later, eight countries bordering the North Sea agreed to significantly accelerate the deployment of offshore wind. According to their Joint Statement, the installed capacity in the North Sea should reach 76 GW by 2030, 193 GW by 2040, and 260 GW by 2050. However, this includes 30 GW that is to be installed by Norway, a non-EU member country (North Sea Energy Cooperation, 2022).

Achieving these goals will be challenging, due to numerous exclusion zones, especially in the North Sea. As a result, only up to 112 GW can be built cost effectively (WindEurope, 2020). To mitigate this issue, already in November 2020, the European Commission published its Offshore Wind Strategy with the goal of increasing installed offshore wind capacity in the EU from 12 to at least 60 GW by 2030 and 300 GW by 2050.

In addition, at least 1 GW of ocean energy should be installed by the end of the current decade, subsequently scaled up to 40 GW by 2050. For this purpose, the Commission would facilitate cooperation between member states, especially in terms of spatial planning. To reduce the potential for conflicts between offshore wind energy projects and nature protection, the Commission has also published a guidance document on wind energy development and nature legislation (European Commission, 2020h, 2020d).

Solar

Almost 27 GW of solar PV was installed in 2021, 34% more than in 2020 and much above the initial prediction of 22 GW (Solar Power Europe, 2020, 2021). As a result of these additions, some of which came later in the year, solar PV generation increased by 17 TWh, or 14% of the additional electricity demand in comparison to 2020 (European Commission, 2022g).

The increase in capacity in 2021 was almost 5 GW higher than initial projections by Solar Power Europe. In their most recent projections, improved national policy conditions in some EU member states will result in much higher growth in installed capacity: by around 39 GW in 2022 (Solar Power Europe, 2022b). Doubling the value of the imports of solar PV panels from China, the source of 80% of solar panel imports, in the first eight months of 2022 indicates that these projects may even be exceeded (Bruegel, 2022c).

The significant dependency on imports constitutes one of the major risks in scaling up the EU’s solar PV installations. To develop the EU supply chain, in the framework of the REPowerEU Plan the European Commission suggested creating the Solar Photovoltaic Industry Alliance to bring together different actors, such as industry, research institutes and consumer associations. In October 2022 the Commission formally endorsed the Alliance’s goal of developing 30 GW of annual solar manufacturing capacity by 2025 (European Commission, 2022b, 2022d).

At the beginning of May 2022, Ministers of the Environment, Climate action and Energy from Austria, Belgium, Lithuania, Luxembourg, and Spain sent a letter to the European Commission calling for a significant improvement in the financial and legal framework, that would result in combined solar PV capacity of at least 1 TW of solar PV by 2030 (Solar Power Europe, 2022a). This would be a sixfold increase in comparison to 2021, when an estimated 165 GW were connected to the grid (Solar Power Europe, 2021).

As part of its REPowerEU Plan the Commission adopted the EU Solar Energy Strategy, with the goal of increasing the installed capacity of solar PV to 320 GW by 2025 and 600 GW by 2030. This would require approximately 45 GW of installed PV annually (European Commission, 2022c). With almost 40 GW set to be installed in 2022, and up to 66 GW of solar PV to be installed in 2025, these projections were from before the ongoing energy crisis, which has accelerated the deployment of solar PV. It’s clear that such a goal is significantly below what’s possible and what’s needed to decarbonise the EU’s electricity sector and reduce dependency on imported fossil fuels.

Renewable Energy Financing Mechanism

To facilitate the development of renewables, in September 2020 the EU adopted a regulation implementing the Renewable Energy Financing Mechanism (European Commission, 2020g). This mechanism allows member states to reach their renewable energy goals by funding the development of renewables in other EU member states where it could be more cost competitive. The potential of the Mechanism is significantly increased by also opening it to private investors, and the possibility of using resources from the recovery fund.

Some of the proceeds from the taxation of the additional profits resulting from high energy prices – as agreed upon by member states in September 2022 – may be used to finance development of renewables through this mechanism (Council of the European Union, 2022b).

Finally, in its commitment to contribute to the development of offshore wind in the North Sea, Luxembourg, which does not have maritime space, planned to contribute to achieving this goals through the Renewable Energy Financing Mechanism (North Sea Energy Cooperation, 2022).

In February 2021, the EU established the European Climate, Infrastructure and Environment Executive Agency (CINEA), which will facilitate implementation of this mechanism, along with other actions (European Commission, 2021b).

Permitting

In conjunction with its REPowerEU Plan, in May 2022 the Commission also published its recommendations on speeding up permitting for renewable energy projects. It suggests that member states define such projects as “being in the overriding public interest”. Such a definition would grant these projects priority when they need to be outweighed against other priorities. In addition, the duration of permit-granting for solar energy should be limited to a maximum of three months. Finally, member states should designate renewable go-to areas in which renewable energy projects could be rapidly deployed (European Commission, 2022c).

Coal phase-out

High fossil gas prices and an increase in electricity consumption resulted in a growth of coal-based electricity generation from 364 TWh in 2020 to 436 TWh in 2021. This was still slightly below 2019 levels at 451 TWh. The share of coal in electricity generation increased from 13% to 15% (Ember Climate, 2022b). Despite higher generation, 14 GW or 7.2% of installed coal capacity was retired, mostly in Germany (7.3 GW), Portugal (2 GW), and Spain (1.7 GW). Poland was the only country that added new coal capacity (460 MW) in 2021, but simultaneously retired 450 MW of capacity (Europe Beyond Coal, 2022).

The switch from gas to coal resulted in an accelerated increase in the price of emissions allowances, which reached a record high of EUR 97 in February 2022. In reaction to the illegal Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February, the price of emissions allowances briefly fell to below EUR 60, but soon after exceeded EUR 80 and approached EUR 90 in early May 2022. However, the Commission’s proposal to fund some of the measures suggested in the REPowerEU Plan with EUR 20 bn from the sale of additional allowances resulted in a temporary decrease in the price of the allowances – to below EUR 80. By September 2022 the price of emission allowances fell further to between EUR 65–75 (Ember Climate, 2022a).

In the first nine months of 2022 coal power plants generated 38 TWh, or around 10% more electricity than in than in the same period of 2021 (Bruegel, 2022c). This increase was used to compensate for a significant decrease in electricity generation from nuclear power plants (-84 TWh) and hydropower plants (-63 TWh) as a result of widespread drought. To prepare for any deficit in fossil gas supplies, many member states decided to temporarily bring some coal power plants back into service or to keep them in reserve for the coming 2022/2023 winter.

The current challenging circumstances are being used by member states to justify such temporary measures, but they need to be accompanied by an urgent and massive acceleration in the development of renewables to avoid a repeat of such steps in the winter 2023/2024.

It is more challenging to understand the Commission’s (REPowerEU Plan) proposal to include EUR 2 bn to revamp existing coal power plants and allow for later phase-out and more operating hours. This would allow coal power plants to generate 105 TWh more than in the “Fit for 55" proposal to compensate for some of the 240 TWh reduction in fossil gas generation (European Commission, 2022c). Such a measure would significantly increase the risk of lock-in on the most emissions-intensive source of energy, turning the temporary measure a permanent one.

Fossil gas

In 2021, fossil gas consumption in the EU increased by 4% in comparison to 2020, reaching 412 bcm, the highest level since 2011 (European Commission, 2022j). With 524 TWh generated, fossil gas covered 18% of EU electricity generation in 2021(Ember Climate, 2022b). In the first nine months of 2022 fossil gas power plants generated almost 26 TWh of electricity, or around 6% more than in the same period in 2021 (Bruegel, 2022c).

As in the case of coal, this increased generation was driven by the unplanned switching off of nuclear power plants in France and some other EU member states and reduced generation from hydropower plants caused by drought. Overall, between January and September 2022 fossil gas consumption decreased by 7% in comparison to the same period of 2021 (Bruegel, 2022a).

The illegal Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, and the resulting calls for an embargo on energy imports from Russia, drastically increased the urgency to reduce EU’s dependency on Russian gas. In 2021 the EU imported 137 bcm of fossil gas from Russia, or 33% of its overall fossil gas consumption (European Commission, 2022j), a slight decrease compared to the previous year.

The Commission’s REPowerEU Plan proposes measures that would reduce fossil gas demand by a combined 250 bcm. This reduction is to be driven by replacing fossil gas with low carbon alternatives, demand reduction, and increasing imports from other countries. Around 24 bcm would result from increased coal consumption and 7 bcm from postponing nuclear phase-out plans in Belgium and France. In addition to the EUR 10 bn of additional investment needed for new LNG infrastructure and pipeline corridors, it also includes EUR 2 bn for switching from gas to coal (European Commission, 2022c).

However, the closure of various gas pipelines by Russia resulted in a much faster decrease in gas imports from Russia than initially predicted by the European Parliament. By October 2022 Russian fossil gas imports decreased to 0.5 bcm weekly, less than one fifth of imports from the same period in 2021 and around 7% of total EU fossil gas imports (Bruegel, 2022b). This decrease was compensated by a significant increase in the import of liquefied fossil gas (LNG) and pipeline imports from other countries, as well as some reduction in gas consumption.

By October 2022 EU gas storage was, on average, 93% full, 15 percentage points above the same time last year (Gas Infrastructure Europe, 2022). Early estimates indicate that in Q1 of 2022 fossil gas consumption fell by 8% or 12 bcm, followed by an even steeper decrease in Q2, when consumption decreased by 16% or 14 bcm. Combined, in the first half of 2022 the EU spent EUR 153bn on fossil gas imports compared to EUR 36bn over the same period in 2021 (European Commission, 2022k, 2022l). This would have been at least EUR 11 bn higher without the year-on-year increase in solar and wind generation (Ember Climate, 2022c).

In the meantime, the EU and its member states have accelerated investment in LNG infrastructure. Between September 2021 and October 2022 investment decisions or announcements have been made toward the construction of 16 onshore LNG terminals with a combined capacity of over 89 bcm and 22 floating storage and regasification units (FSRU), with a combined capacity of almost 90 bcm (Bruegel, 2022c).

Combined, the capacity corresponds to 116% of fossil gas imports from Russia in 2021. Over 93% of the onshore capacity and 25% of the FSRU units are set to go online in or after 2024. The Baltic Pipe is also set to deliver 10 bcm of fossil gas annually from Norway, and additional imports via pipelines are planned from Algeria and Azerbaijan (Euronews, 2022a). All of these investments are accompanied by the development of intra-EU pipeline connections.

Such significant investments in fossil gas infrastructure, most of which will go online after the EU has had enough time to develop low carbon alternatives and invest in energy efficiency, are impossible to justify. According to the European Commission’s own calculations the full implementation of the “Fit for 55" package, combined with the impact of higher energy prices, would result in a gas consumption reduction of 156 bcm (European Commission, 2022c) or around 40% of 2021 consumption. These investments will either result in significant stranded assets or will threaten the EU’s emissions reduction goals. To make matters worse, the EU and its member states are encouraging other countries such as Algeria, Angola, Azerbaijan, Egypt, Senegal or Congo to invest in fossil gas extraction (Bruegel, 2022c; Reuters, 2022).

The need for such a significant investment in fossil gas infrastructure has been countered by a recent assessment indicating that the EU can do without Russian gas without investing heavily into fossil fuel infrastructure (European Climate Foundation, 2022).

This can be achieved by accelerating deployment of renewables through fast tracking permitting for wind and solar projects and building human resources capacity for their installation. Investment in energy efficiency and the deployment of heat pumps could significantly reduce gas demand in the buildings sector.

Finally, electrification of the industry whenever possible could make it more resilient for future energy shocks. To fill the temporary gap in fossil gas supply the EU could rely on temporary FSRUs, better utilisation of existing unused capacity, and short-term contracts on gas deliveries.

Industry

Since 2018, emissions from the industry sector have continued to decrease at an accelerated pace. While the almost 3% decrease in 2019 can be explained by increasing energy efficiency and decarbonising the sector, the 8.6% decrease in 2020 was driven mostly by the pandemic-induced recession (Eurostat, 2022c). While data for 2021 are not yet available, emissions are expected to rebound due to the economic recovery before they fall again in 2022 due to a significant increase in fossil fuel prices, implementation of efficiency measures, and a decline in manufacturing.

To decouple emissions from economic growth, in March 2020, the European Commission published its New Industrial Strategy for Europe with a number of measures that would allow industry to contribute to achieving the “climate neutrality” goal (European Commission, 2020b). Some of these measures have been further elaborated in the Chemicals Strategy published in October 2020 (European Commission, 2020e). In May 2021 the Commission updated the Industrial Strategy, reflecting the changes brought about by the pandemic (European Commission, 2021u).

The update of the EU’s Industrial Strategy was accompanied by Staff Working Document “Towards Competitive and Clean European Steel”, which pointed out that the steel sector, responsible for 5.8% of the EU’s total emissions (including indirect emissions), could be “one of the first hard-to-abate sectors to produce green products”. The document listed a number of measures planned or already taken to accelerate innovation in the steel sector and deployment of low carbon steel. Apart from different streams of funding (e.g. Innovation Fund, InvestEU Fund, Recovery Fund), it also listed measures that could increase demand for low carbon steel (e.g. Construction Products Regulation, Sustainable Products Initiative, Public Procurement policies) (European Commission, 2021t).

While emissions from the industry sector are covered by the EU emissions trading scheme and thus are affected by the increasing price of emissions allowances, the impact of this instrument is lessened by the fact that companies producing products on a so-called “leakage list” receive free allowances up to the average emissions of the 10% most efficient installations in the sector, or subsector, potentially affected by the risk of carbon leakage. Increasing stringency of the criteria that need to be fulfilled by a product to be listed as affected by carbon leakage resulted in a decrease in the share of allowances received for free by the manufacturing industry from 80% in 2013 to 30% in 2020 (European Commission, 2020c).

One of the measures suggested in the Commission’s New Industrial Strategy, and also referred to in the European Green Deal, is the introduction of a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) – an additional charge on energy-intensive products from countries with no or very lax climate mitigation measures. In July 2021, the Commission tabled a proposal on the CBAM that would require EU importers of certain energy-intensive products to purchase CBAM Certificates, mirroring the price of emissions allowances traded in the framework of the EU ETS. The introduction of the mechanism should result in a steady phase-out of free allowances (European Commission, 2021m).

In July 2020, the Commission presented its hydrogen strategy with the goal of realising 40 GW of installed electrolyser capacity in the EU by 2030 to generate green hydrogen from renewable sources of energy. This is to be complemented by a further 40 GW of electrolyser capacity installed in neighbouring countries.

The combined investment needed to develop this capacity, scale up solar and wind generation, and develop the necessary electricity and dedicated pipeline connections has been estimated to be between EUR 309–447 bn. An additional EUR 11 bn would need to be invested in retrofitting the existing hydrogen production plants with carbon capture and storage infrastructure (European Commission, 2020a). While hydrogen can be used in many different sectors, e.g. as storage in the electricity sector, mobility or even heating, its first destination will be the industry sector, especially chemical and petrochemical, where it is currently used as feedstock. In the future, its role will also increase in the steel sector where hydrogen can be used instead of carbon monoxide in a reduction process (Hydrogen Europe, 2020).

Industry emissions intensity (per GVA) MER

Transport

After a continued increase since 2013, emissions from the transport sector decreased for the first time in 2020, by almost 14%, driven mostly by the pandemic-induced reduction in mobility and the economic crisis (European Environment Agency, 2022a). The post-pandemic rebound in 2021 resulted in emissions increase by 8% compared to 2020, but they remained 7% below the 2019 levels (European Environment Agency, 2022c). Overall, emissions in 2021 were 15% higher than in 1990, making transport the only major sector where emissions increased over the preceding 30 years. In 2022 high fuel prices and an increasing uptake of electric vehicles (EV) may result in declining emissions.

In reaction to increasing fossil fuel prices, many governments slashed fuel taxes dampening the impact on energy demand reductions. The temporary measures introduced by member states by the beginning of September 2022 will result in almost EUR 29 bn of fossil fuel subsidies. If prolonged, this would increase to EUR 52 bn for the whole year (Transport&Environment, 2022).

As the transport sector—with the exception of intra-European aviation—is not covered by the EU ETS, the European Union and its member states are trying to reduce emissions from the sector in four ways: (i) adopting sectorial renewable energy targets, (ii) introducing CO2 emissions standards for new vehicles, and (iii) increasing the share of zero and low emissions vehicles, and (iv) encouraging a modal shift, which also has an important role to play, particularly from road and air to rail transport.

Sectoral renewable energy targets

The 2009 Renewable Energy Directive introduced a 10% target for energy from renewable sources in transport by 2020 (European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, 2009). The target was exceeded slightly, with 10.1% of energy consumed in the transport sector coming from renewable sources (European Environment Agency, 2021).

The 2018 Renewable Energy Directive (REDII) introduced a new goal of a 14% share of renewables in the transport sector by 2030. However, the proposal for the revision of the directive currently negotiated between the Council of Ministers and the Parliament allows member states to choose between a target expressed as the share of renewable energy within the final consumption in the transport sector, and a greenhouse gas emissions intensity target. In addition, the share of biogas and advanced biofuels should increase to 2.2% and the share of renewable fuels of non-biological origin should increase to 2.6% by 2030 (Council of the European Union, 2022j; European Commission, 2021f).

In July 2021, the Commission also proposed a new regulation aimed at increasing the role of sustainable fuels in aviation. According to the proposal, their share should increase from 2% in 2025 to 5% in 20230, 32% in 2040, and 63% in 2050. An increasing role in achieving these goals should be played by synthetic aviation fuels, mainly hydrogen generated from renewables (European Commission, 2021n).

For maritime transport, the proposal of the FuelEUMaritime Regulation does not propose any specific share of renewables. However, their uptake is promoted by a requirement to decrease emissions intensity by 2% in 2025, 6% in 2030, 26% in 2040, and 75% by 2050. In addition, when at berth, ships will be required to connect to onshore power supply, if such is available. To reduce emissions-intensity, ships may also use onboard solar for electricity generation or wind for assisted propulsion (European Commission, 2021q).

CO2 emissions standards for vehicles

Emissions intensity of land-based passenger transport

The binding regulation obliges car manufacturers to decrease average emissions of new passenger cars and vans by 15% from 2025. From 2030, an average new passenger car is to emit 37.5% less CO2 than in 2021, whereas the emissions standards for new vans are to improve by 31%. The amendment of the regulation tabled by the Commission in July 2021 strengthened the 2030 target and added emissions reduction for new vehicles of 100% in 2035 (European Commission, 2021k; European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, 2019).

| Vehicle type | Emissions reduction in comparison to average emissions of new cars in 2021 according to Regulation 2019/631 | Emissions reduction in comparison to average emissions of new cars in 2021 according to Commission’s Proposal from 14 July 2021 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starting in 2025 | Starting in 2030 | Starting in 2030 | Starting in 2035 | |

| Passenger cars | 15% | 37.5% | 55% | 100% |

| Light Commercial Vehicles | 15% | 31% | 50% | 100% |

These emissions reductions cannot be directly applied to the existing 95 gCO2/km limit for passenger cars for 2021 and 147 gCO2/km limit for vans in 2020: due to numerous exceptions and different methodology, the real average emissions of new vehicles will very likely be higher.

In June and July 2022, the Council of Ministers and the European Parliament adopted their respective positions regarding the European Commission’s proposal. Both institutions approved the emissions reduction goals proposed by the Commission.

However, they differed in terms of the scope and duration of the derogations from meeting these targets by car manufacturers (Council of the European Union, 2022e; European Parliament, 2022b). These positions have been criticised by various stakeholders for their lack of interim and stricter emissions reduction targets, especially between 2025 and 2029, too many bonuses and derogations, and the lack of realistic CO2 ratings of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles. The independent think tank Transport and Environment also suggests banning the sale of combustion vehicles with emissions above 120 gCO2/km from 2030 (Agora Verkehrswende, 2021; The European Consumer Organisation, 2021; Transport & Environment, 2022).

In October 2022, the representatives of the Council and the Parliament agreed on the goals of reducing emissions from the new passenger cars and vans by 100% by 2035. The major weakness of this agreement is that with emissions reduction by 55% and 50% by 2030 in comparison to 2021, most of the effort will only take place after 2030. In addition, car manufacturers may still exceed these limits by paying €95 per gram CO2/km for each new vehicle sold (Council of the European Union, 2022c). These weaknesses need to be addressed by the member states by accelerating deployment of electric mobility already in this decade and creating attractive alternatives to passenger cars.

Existing legislation has had a mixed impact on passenger vehicle emissions. After average emissions from new cars registered in the EU fell from 123 gCO2/km in 2019 to 108 gCO2/km in 2020, they increased again to 116 gCO2/km in 2021. In almost all Eastern European countries the emissions intensity of new cars exceeded 130 gCO2/km. Only in Romania did they remain slightly below that benchmark at 126 gCO2/km. While, on average, emissions from new passenger cars sold in Western European countries were slightly lower, only in Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands were they below 100 gCO2/km (ACEA, 2022b).

In February 2019, the European Parliament and Council agreed on emissions standards for heavy duty vehicles. Emissions from new vehicles should decrease by 15% in the period 2025–2029 and by 30% from 2030 onwards, in comparison to emissions of the new vehicles sold between July 1, 2019, and June 30, 2020. The regulation also includes a 2% benchmark for the share of zero and low-emission vehicles (ZLEV). Whereas failing to meet this benchmark does not result in any negative consequences, exceeding it leads to more lenient emissions standards for the remaining vehicles (The ICCT, 2019).

Promoting low-carbon vehicles

Zero emission fuels for domestic transport

After a significant increase in the share of EVs in new car sales in the EU from 10% in 2020 to 18% in 2021, the increase slowed in the first half of 2022, with less than 19% of sales being battery electric or plug-in hybrids. On a positive note, the share of battery-only electric vehicles among total EV sales increased from 44% to 53%. (ACEA, 2021, 2022a).

The differences between member states increased even further: with a 52% EV sales share in Sweden, and 34% in Denmark and Finland, the Nordic countries recorded the highest EV share of sales, followed closely by the Netherlands with almost 31% and Germany with 25%. Despite some increases, the EV share of sales in Slovakia, Croatia, Czechia, Bulgaria, Cyprus, and Poland remained at a very low level – between 3-5% in the first half of 2022 (ACEA, 2022a).

The EU is trying to stimulate the development of the market for clean vehicles by introducing binding clean vehicle procurement quotas for public authorities. In February 2019, the EU Parliament and Council agreed on an amendment to the Directive on promoting clean and energy efficient vehicles. The Directive requires public authority vehicle procurement (e.g. for public transport) to take CO2 emissions and the emissions of other pollutants into account. It also sets a minimum share of clean heavy-duty vehicles (trucks and buses) in the total number of heavy-duty vehicles contracted by member states.

These shares differ depending on the member state and type of vehicle. For example, in the period 2021-2025, between 24% (Romania) and 45% (majority of the EU member states) of buses procured by public communities should be clean or zero emissions. For the period 2026-2030, these shares increase to between 33% and 65% (European Parliament, 2019).

Underdeveloped charging infrastructure remains a major hindrance to EV uptake. In July 2021 the Commission tabled a proposal that would replace the Directive on the Deployment of Alternative Fuels Infrastructure from 2014 with a regulation that includes a number of mandatory national targets. For example, for each battery electric light-duty vehicle registered in their territory, a total power output of at least 1 kW must be provided through publicly accessible recharging stations. For plug-in hybrids this factor amounts to 0.66 kW for each vehicle. There should also be a recharging point every 60 km along the motorways that constitute part of the Trans-European transport Network (TEN-T) consisting of fast charging points—at least 300 kW from 2025 and at least 600 kW from 2030.

Additional targets are specified for hydrogen charging stations and charging stations for heavy-duty vehicles. The proposal also requires the development of charging stations for LNG for heavy duty vehicles and ships “unless the costs are disproportionate to the benefits, including environmental benefits“. This requirement could significantly increase dependency of the transport sector on fossil gas (European Commission, 2021p).

Modal Shift

The EU aims to strengthen the position of railways in comparison to other modes of transport, by increasing competition between the operators and investing in rail transport infrastructure, as well as other measures. However, these efforts have still not had an impact on shifting freight transport from road to rail: between 2013 and 2018, the share of freight transported by rail remained constant at between 18–19%. By 2019 it fell to 17.7%, reaching just 16.8% in 2020 (Eurostat, 2022b).

To improve the situation, in the Framework of the European Green Deal the European Commission was planning to present a revised proposal of the amendment of the 1992 European Combined Transport Directive in 2021. After public consultation ended in May 2022, the Commission was planning to table a proposal in Q3 of 2022 (European Commission, 2022n).

Whereas in passenger transport the number of passenger-kilometres increased slightly over the last decade, this increase was much faster than in the case of rail. This is especially the case in Eastern European countries, where a shift from train to plane could be clearly observed with more passenger-kilometres travelled by plane than by train in most of the countries. Due to the massive investment in new motorways, co-financed to a large degree from European sources, the popularity of passenger cars increased significantly. This has been accompanied by only a modest improvement in railway infrastructure (Climate Analytics et al., 2020).

The increase in the role of aviation has been strongly undermined by the COVID-19 related limits on international travel and it remains to be seen how soon and whether it will fully recover. In the meantime, the funding to be made available on climate action in the framework of the Multiannual Financial Framework and NextGenerationEU Recovery Fund presents the opportunity to replace domestic and, in some cases, intra-EU flights with rapid train connections.

Buildings

After a continuous decrease in direct emissions from fuel consumption in households since 2018, emissions in 2020 increased slightly – by 0.2% – in 2020. This could be explained by the colder winter 2019/2020 and the pandemic. In the context of a significant and temporary decrease in emissions in that year, the share of these emissions in the EU total increased to 10% (Eurostat, 2022c). However, this excludes indirect emissions, for example from electricity generation. With indirect emissions and including commercially used buildings, this sector is responsible for 36% of the EU’s total emissions and 40% of energy consumed (European Parliament, 2021).

In 2020 the majority of these emissions were coming from fossil gas consumption, which accounted for almost 32% of EU household final energy consumption in 2020 – a comparatively constant share since the late 1990s. The share of other fossil fuels – oil and coal – has steadily decreased since the 1990s:

- The share of coal burned directly in households for heating decreased from 11% in 1990 to less than 3% in 2020, with 77% of the coal burnt for this purpose taking place in Poland.

- The share of oil decreased from 25% in 1990 to 11% in 2018, before increasing to over 12% in 2020.

- The share of renewables has more than doubled to just above 20%.

- The consumption of electricity in households also increased: from 18.5% in 1990 to almost 25%.

- The share of district heating decreased slightly from 10% to 8%, but with significant differences between member states, with more than a quarter of final energy consumed in households in the Nordic and Baltic countries coming from this source of energy (Eurostat, 2022a).

Heat pumps

There are clear indications that the ongoing energy crisis will have a significant impact on the buildings sector’s energy mix. Already in 2021 the sale of heat pumps – the most effective option to facilitate an electrification of buildings’ heating and reduce final energy demand – increased by 34% and reached almost 2.2 million (European Heat Pump Association, 2022). The growth in 2022 may be even bigger, especially in countries affected the most by the ongoing energy crisis:

- In Poland, heavily dependent on coal imports from Russia for the household sector, the sale of heat pumps in H1 of 2022 increased by 96% in comparison to H1 2021 (Port PC, 2022).

- In the Netherlands and Austria the sale of heat pumps doubled in the same period, whereas in Finland, in which this source of energy is already dominating, an increase by 80% has been registered (Energate Messenger, 2022; Finnish Heat Pump Association, 2022; Vereniging Warmtepompen, 2022).

- While in Germany the sale of heat pumps increased by only 25% in the same period, the country registered a significant increase in the number of applications for funding energy efficiency and renewable energy measures in the buildings sector (BAFA, 2022; BDH Industrie, 2022)

Unfortunately, this significant increase in demand has resulted in long waiting times for heat pump installations and approval of applications for public support. It is therefore of great urgency for the EU and member states to facilitate the scaling-up of manufacturing of the necessary equipment and to train the much-needed workforce. It also needs to ban any kind of support for the installation of fossil fuel-based boilers and decide on a phase-out date for them.

Energy efficiency and renovations

Reducing buildings’ energy demand through home insulation is another key aspect to reducing energy consumption. Despite the adoption of the Energy Performance Buildings Directive (EPBD Directive) in 2010, the EU annual renovation rate remains at around 1% of the buildings stock (European Parliament, 2021).

To increase the renovation rate, in October 2020 the Commission launched its ‘Renovation Wave’ with a number of goals and measures to reduce emissions and energy consumption in the buildings sector, such as providing more adequate and targeted funding, increasing the availability of energy-efficiency and recycled building materials, the introduction of stricter and mandatory minimum energy performance standards, and increasing the role of digitalisation and renewables. As a result, by 2030, at least 35 million buildings are to be renovated and the renovation rate doubled.

To achieve these goals, in December 2021 the European Commission proposed revising the EPBD Directive (European Commission, 2021i). One of the major improvements concerns implementing EU-wide minimum energy performance standards to replace the existing standards determined by each member state.

It also includes a definition of zero emissions buildings and states that, from 2030, all new or deeply-renovated buildings must fulfil the criteria for such a building: they should consume no more than 60 kWh/m2 (for Mediterranean climatic zone) and 75 kWh/m2 (for Nordic climatic zone) annually, all of which should come from renewable sources or district heating.

It also introduces “renovation passports” that should increase transparency and help homeowners identify the best timing for different interventions resulting in lower energy consumption and higher shares of renewable energy. As of October 2022, the Council of Ministers and the European Parliament are still to agree on the final version of the Directive.

The European Commission’s May 2022 REPowerEU Plan includes further amendments to the EPBD Directive. Solar energy installations must be on all new public and commercial buildings from 2027, on all existing public and commercial buildings from 2028, and on all new residential buildings from 2030 (European Commission, 2022e). The higher overall proposed renewable energy target would also result in a higher share of renewables in the energy consumed in buildings: instead of 49% the plan proposes that at least 60% of energy consumed in this sector should come from renewables, almost three times as much as in 2020 (European Commission, 2022c).

The proposal also amends the Energy Efficiency Directive, tabled by the Commission in July 2021, which includes some measures mentioned in the Renovation Wave Strategy, e.g. creation of one-stop-shops for the provision of technical, administrative, and financial knowledge about increasing energy efficiency and house renovation. Member states should also ensure that a mechanism is introduced that would ensure that both tenants and homeowners benefit from the implementation of energy efficiency measures. It also encourages national governments to set up Energy Efficiency National Funds to implement energy efficiency measures (European Commission, 2021h).

An additional tool that should facilitate emissions reductions in the buildings sector is the proposal to adopt an adjacent EU ETS for the buildings and transport sectors. The Commission’s proposal, also presented in July 2021, suggests creating such an EU ETS (“ETS2”) to start operating in 2025. It should result in emissions reductions from these two sectors of 43% below 2005 levels by 2030: 18 percentage points below the emissions reduction in the already-existing EU ETS covering electricity and industry sectors (European Commission, 2021g).

At the same time, emissions from the buildings are also to be covered by the amended Effort Sharing Regulation which includes binding emissions reduction targets for sectors not covered by the initial EU ETS. These targets result in average emissions reduction at 40% - instead of 30% in the initial regulation (European Commission, 2021j).

Buildings emissions intensity (per floor area, residential)

Agriculture

After a continual decrease between 1990 and 2006, especially in Eastern European countries, emissions from the agriculture sector remained at a comparatively constant level of between 375 and 390 MtCO2e. After an increase by 0.2% in 2020, they constituted 12.4% of the EU’s total emissions—a share that increased modestly from 10% in 1990 due to a slower rate of emissions decrease than overall emissions (Eurostat, 2022c).

Currently, emissions from the agricultural sector are covered by the Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR), which covers all sectors, except for those covered by the EU ETS and LULUCF. According to the Regulation, combined EU emissions from the ESR sectors are set to decrease by 30% below 2005 levels by 2030, with different goals for different EU member states (European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, 2018c). In July 2021, the Commission presented a proposal that increases this goal to 40% to reflect the higher overall emissions reduction goal. According to the proposal of the ESR regulation, emissions from agriculture should be climate-neutral by 2035 (European Commission, 2021l).

Furthermore, in its proposal the Commission suggested to increasingly deploy carbon farming schemes and certification for carbon removals through 2030. These schemes will especially promote the creation of new business models that are focused on increasing carbon sequestration in agriculture and other land types. Land users (i.e. farmers and foresters) are expected to avoid further depletion in their carbon stock, especially in soils. In December 2021 the Commission published its Carbon Farming Communication which lists a number of measures that farmers in the EU can introduce to increase carbon storage in the soil and be rewarded from Common Agriculture Policy resources (European Commission, 2021s).

Forestry

The land use, land-use change and forestry sector (LULUCF) has, since 1990, constituted a sink of emissions averaging around 300 MtCO2e. However, since 2017 the sink has begun significantly decreasing, amounting to only 230 MtCO2e in 2020. This change has mostly been driven by Czechia, Estonia, and Latvia joining Denmark, Ireland, and the Netherlands as the net emitters from the sector, as well as a significant reduction of the sink in Germany, Poland, and Italy (Eurostat, 2022c).

The EU Regulation for the Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry regulates the accounting of the GHGs emissions and removals from the LULUCF sector. It allows the use of net removals from this sector to comply with the targets in the non-EU ETS sectors by up to 280 MtCO2 from 2021–2030 (European Commission, 2016). The Regulation includes a no-debit rule meaning that emissions from deforestation could be offset by either afforestation or improved management of existing forests (European Commission, 2016). However, this target is weakened by the possibility of using 2021–2025 LULUCF emissions reductions to offset emissions in the second half of the decade.

In July 2021, the Commission tabled a proposal amending the LULUCF Regulation, under which the flexibility on the accounting of emission reductions from managed forests will still be in place in the period 2021–2025 and will be adjusted in 2026 in line with the European Climate Law. The proposal also includes a goal of increasing the sinks to 310 MtCO2e in the LULUCF sector in 2030. The Council and the European Parliament still need to come to an agreement on a compromise text of the Regulation.

Waste

Waste management is the only major sector where emissions have continuously decreased in the EU since the 1990s. While at a slower rate, this decrease continued in 2020, with emissions falling by around 1%. Overall, emissions from waste management decreased by almost 35% between 1990 and 2019 – as fast as total emissions. As a result, the share in total emissions remained stable at around 3.6% (Eurostat, 2022c).

Waste is covered by the Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR), next to transport, buildings, and agriculture. According to the currently binding legislation, combined emissions from these sectors need to decrease by 30% between 2005 and 2030. The Commission’s proposal amending this regulation increases this emissions reduction goal to 40% (European Commission, 2021j).

The main legislation influencing EU’s waste management policy is the Waste Framework Directive which aims at reducing the amount of waste that end up in landfills and contributes to climate change by promoting recycling and reuse of products (European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, 2008). In addition, the EU is facilitating a transition towards a circular economy. In 2015 it adopted a respective action plan with a list of 54 actions that would for example make products more durable and make it easier to repair, upgrade, or remanufacture after their use. Product labelling should also make it easier for the European customers to make more informed decisions when taking into consideration products’ environmental impact (European Commission, 2015).

In March 2020 the EU adopted a new Circular Economy Action Plan. The plan adapts the EU’s waste policy to the 2050 climate neutrality goal by building on and concretising many of the suggestions made in the initial action plan from 2015. It also suggests integrating life cycle assessments in public procurement. The impact of circularity on climate change mitigation should also be reflected in modelling tools applied at the national and European levels, and taken account for in the revisions of the National Energy and Climate Plan (European Commission, 2020f).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter