Policies & action

We rate Türkiye’s current policies and action as “Highly insufficient” when compared to its fair share contribution as this metric is more favourable than the modelled domestic pathways. The “Highly insufficient” rating indicates that Türkiye’s policies and action in 2030 lead to rising, rather than falling, emissions and are not at all consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C. If all countries were to follow Türkiye’s approach, warming could reach over 3°C and up to 4°C.

The CAT estimates that Türkiye’s emissions will be between 534–611 MtCO2e in 2030 (excluding LULUCF) under current policies and action, which means Türkiye is on track to achieve its updated NDC target based on our estimate. To improve its Policies and Action rating, Türkiye needs to focus on adopting further policies and action to stop its emissions growth and start reducing emissions towards decarbonisation.

For a full explanation of the methodology behind our current policy pathway for Türkiye, please see the Assumptions tab.

Policy overview

A key feature of Turkish policy planning involves reducing its reliance on fossil fuel imports. In 2022 alone, Türkiye’s net energy trade deficit was USD 81bn, placing a burden not only on its economy but also leaving it vulnerable to volatile commodity markets and geopolitical shifts (Türkiye Cumhuriyet Merkez Bankası (Central Bank of the Republic of Türkiye), 2023; Ugurtas, 2022). As a result, increasing energy independence is a strategic goal of the Turkish government, with diversification of the energy mix central to government policy.

Managing energy demand is a first step to reducing reliance on imported fossil fuels. The energy intensity of Türkiye’s economy is above the G20 average, but decreased by 6.2% in 2022 compared to the previous year(Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, 2024b). Reducing the energy intensity of the Turkish economy remains a priority for the government.

However, it is also the fastest growing energy consumer in the OECD (Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2022). Through its 2030 Energy Efficiency Strategy and Action Plan, Türkiye aims to reduce energy consumption by 16% below 2023 levels by investing USD 20bn in energy efficiency projects (Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, 2024b). If realised, these investments could allow Türkiye to further decouple energy consumption from economic growth and reduce dependence on imported fossil fuels.

Türkiye intends to have 120 GW of installed wind and solar capacity by 2035. Along with hydropower and biomass, Türkiye’s installed renewable capacity in 2035 will be 160 GW (Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, 2024c; Turkish Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, 2022).

Meeting the wind and solar targets will involve bringing at least 7.5–8 GW online every year, significantly more than what was envisioned in Türkiye’s 2022 National Energy Plan. However, implementation will need to shift up a gear, as the country is struggling to meet even its National Energy Plan’s targets due to a slower than planned renewables rollout. For example, wind power grew from a negligible share of total electricity generation in 2012 to over 10% in 2022 but has since stalled (Ember, 2025). Regularity changes including streamlining the permitting process and improving investment conditions are intended to stimulate private investment in renewable energy projects.

Despite the improved commitment to renewables, Türkiye has yet to commit to a phase-out plan for coal or fossil gas, which need to be taken out of the energy mix in the 2030s if Türkiye is to align with the 1.5°C temperature goal (Robins, 2023). Instead, Türkiye plans to become a fossil gas hub and continue exploiting coal (Robins, 2023; Turkish Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, 2022). If Türkiye is serious about its 2053 net zero emissions target, then it will need to introduce a plan to phase out fossil fuels.

The most significant piece of industrial policy of 2025 has been the passage of Türkiye’s new Climate Law and its framework for an Emissions Trading System (ETS) in line with the EU’s ETS. If designed to cover major sectors and price carbon competitively, the ETS could be the backbone of emission reductions in Türkiye’s industry sector and help to mitigate some of the more severe impacts of the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). CBAM will levy a carbon tax on certain products imported into the EU if they fail to align with EU emissions standards (European Commission, 2024).

Ramping up production of Türkiye’s domestically produced electric vehicle (EV), the Togg, and high-speed electric trains forms an important part of Türkiye’s industrial strategy, which can support domestic uptake while opening a new revenue stream from exports. Türkiye also plans to invest USD 298bn up to 2053 in the transport sector. Sectoral targets include increasing the share of rail in passenger transport to 5.31% and to 20.12% in freight transport by 2035, up from 2019 levels of 0.89% and 3.13%, respectively (Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Transport and Infrastructure, 2022).

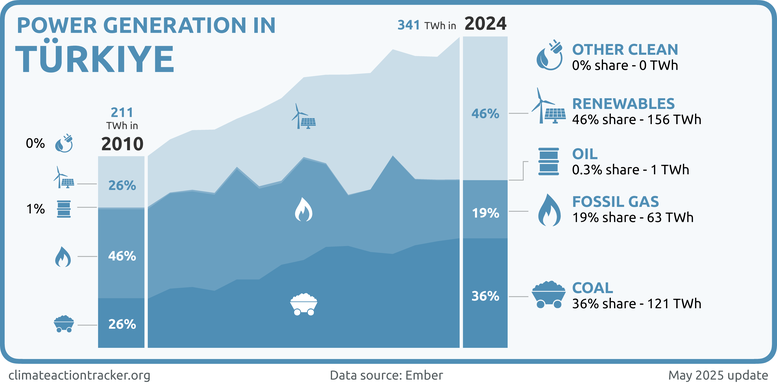

Power sector

Fossil fuels met 55% of Türkiye’s electricity supply in 2024 (Ember, 2025). Reliance on fossil fuel imports has driven efforts to diversify the mix, though imported coal continues to drain Turkish finances and imperil efforts to align with 1.5°C (Ember, 2025; Türkiye Cumhuriyet Merkez Bankası (Central Bank of the Republic of Türkiye), 2023).

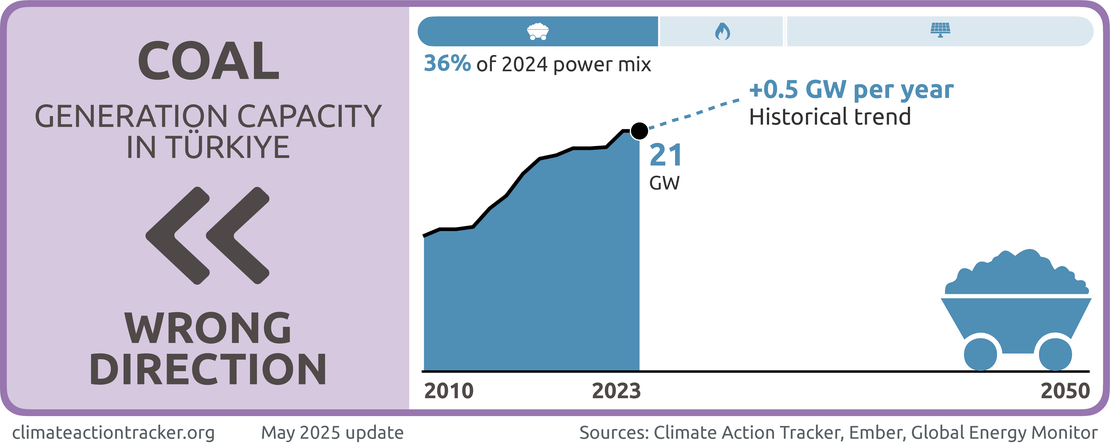

Türkiye’s power sector is thus a tale of two stories; wind and solar are on the rise, but so is coal. Just as there are efforts to speed up the rollout of renewable energy, Türkiye became the largest producer of coal-fired electricity in Europe in 2024, when it overtook Germany (Ember, 2025). It is possible that coal power may be close to peaking in Türkiye, although it provides over a third of Türkiye’s energy supply and the government has not committed to a phase-out plan (Ember, 2025). Meanwhile, Türkiye continues to pour money into oil and fossil gas exploration, with plans for 270 drilling operations in 2025 (Türkiye Today, 2024).

A 1.5°C compatible Turkish power sector requires a targeted shift away from coal and fossil gas, building on the promising momentum in renewables. The Turkish government needs to double down on renewables by rolling out wind and solar faster – to 90 GW by 2030 and 150 GW by 2035 – while developing a fossil fuel phase out plan.

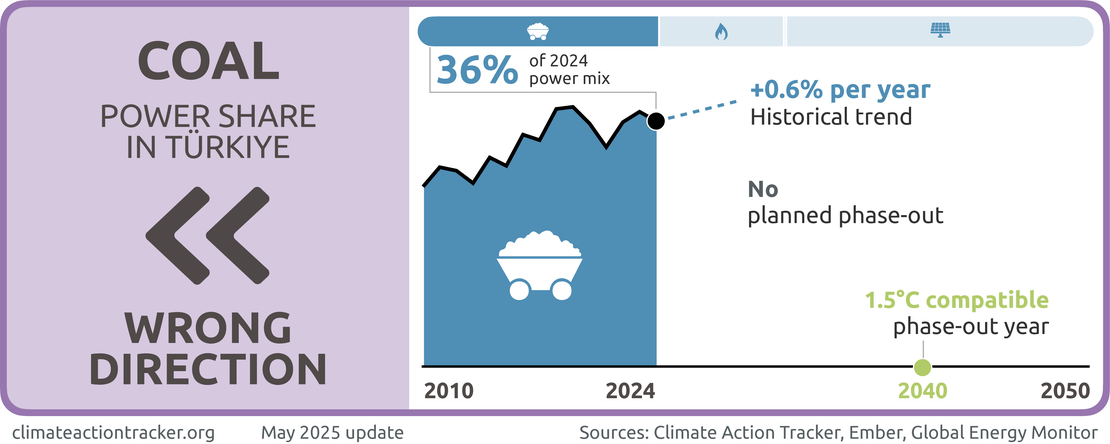

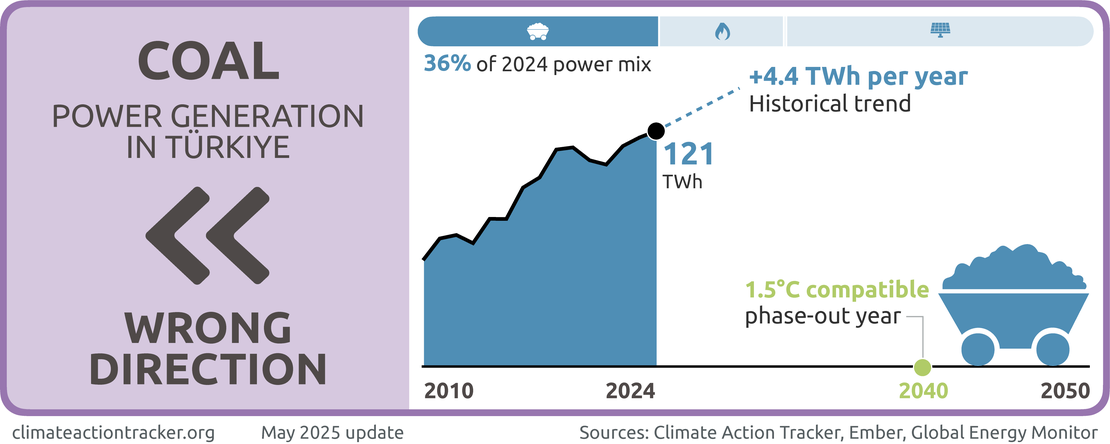

Coal

While coal’s share in the electricity mix slightly declined in 2024, it maintains a significant share, accounting for 36% of electricity generation in 2024 (Ember, 2025). This stands in sharp contrast with what is needed to limit warming to 1.5°C, which would see Türkiye cut coal’s share in electricity generation to single digits by 2030 and 0–3% by 2035 (Climate Action Tracker, 2023). Due to declining investment interest along with growing citizen opposition, much of Türkiye’s planned coal capacity extensions have been shelved. However, no phase-out plans exist, and coal continues to factor into long term energy planning continues. As a result, we evaluate coal in Türkiye as moving in the “Wrong direction.”

Türkiye did not adopt COP26’s commitment to a coal exit. Although at the start of 2024 the Turkish government openly supported exploiting the country’s coal reserves and had approved extensive deforestation in order to expand coal mines, local resistance and legal action led to the cancellation of the vast majority of planned coal projects (Global Energy Monitor, 2024b, 2024a; Hummer et al., 2024). This trend is emblematic of wider global trends, whereby citizen opposition, mounting financial risks and decreasing investment interest have led to the cancellation of projects (Global Energy Monitor, 2024a; World Resources Institute, 2023).

Türkiye’s plans for its domestic coal reserves – and the subsequent cancellation of those plans – only tells half the story. Although domestic coal reserves were intended to reduce dependency on imported fossil fuels, Türkiye remains heavily reliant on imported Russian coal. In 2023 around half of Türkiye’s coal capacity was met by imports, racking up significant costs (Ember, 2025).

Cancelling most planned coal capacity is a positive step towards weaning the country off coal. The Turkish government should now develop a coal phase-out plan to align with 1.5°C and ensure an orderly and just transition for Turkish coal mining communities.

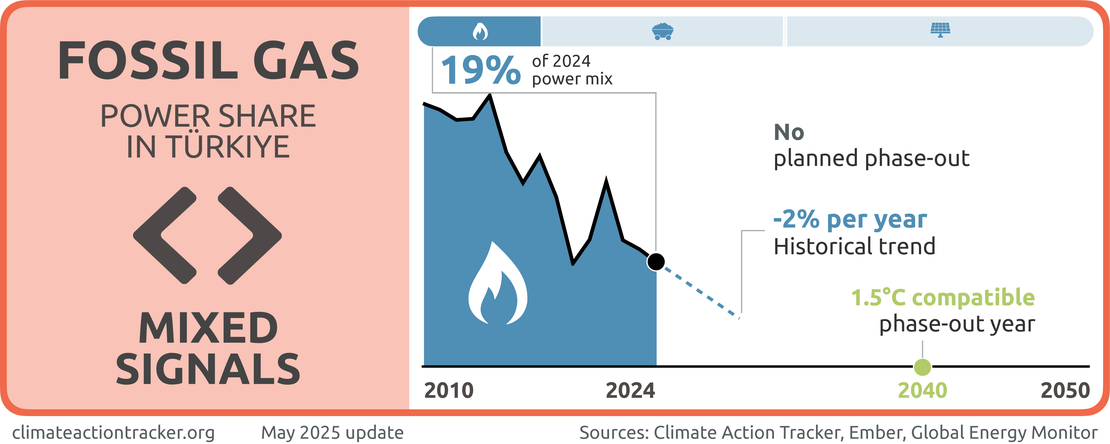

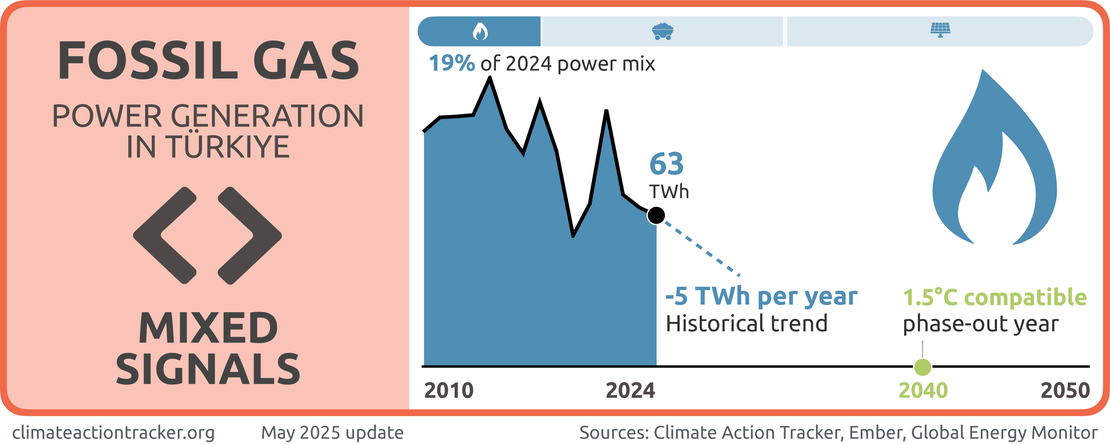

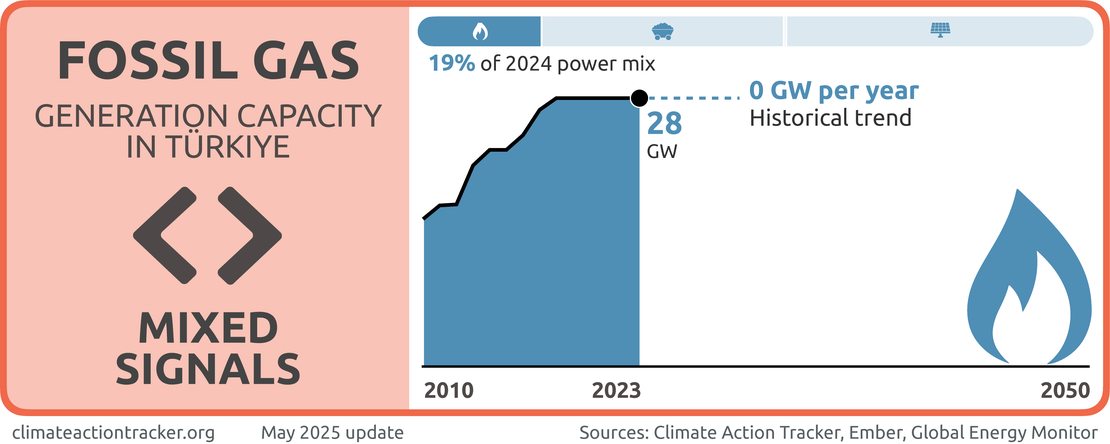

Fossil gas

Fossil gas made up 19% of Türkiye’s electricity supply in 2024 (Ember, 2025). Despite 1.5°C benchmarks requiring that share to fall to 0-3% by 2035 (Climate Action Tracker, 2023), Türkiye intends to maintain that 19% until 2035, and aims to become a fossil gas trading hub (Turkish Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, 2022). To be 1.5°C compatible, Türkiye would need to phase out fossil gas by 2040.

We evaluate fossil gas in Türkiye as "Mixed signals." Despite the declining share of fossil gas in electricity generation, Türkiye is pouring money into exploration for new fossil gas fields and aims to become an international fossil gas hub (Daily Sabah, 2024).

In recent years, Türkiye has strategically focused on diversifying its fossil gas resources. Russia has long been Türkiye’s main supplier of fossil gas. Efforts to diversify supply have seen the share of Russian gas in total gas imports fall from 58% in 2013 to 42% in 2023 (Energy Market Regulatory Authority, 2023, 2024). Other major suppliers include Azerbaijan, Iran, and the US (Energy Market Regulatory Authority, 2024).

Diversifying the fossil gas supply has also taken the form of increasing domestic production, a choice that goes against the latest IEA findings that fossil-fuel use is on track to peak this decade, and no new oil and gas investments are needed in a 1.5C compatible world (Evans, 2025). The discovery of the Sakarya gas field in the Black Sea has been Türkiye’s largest fossil gas discovery to date (Daily Sabah, 2022; IEA, 2021). Production began in 2023, and supply from the Sakarya gas field is expected to grow in the coming years (Energy Market Regulatory Authority, 2024; Offshore Technology, 2023). Oil and fossil gas exploration is a core priority for the Turkish government, with 2024 seeing record extraction and plans for 270 drilling operations in 2025 (Daily Sabah, 2024; Türkiye Today, 2024).

In 2024, Türkiye signed a fossil gas deal with Hungary, a deal that represents the first time Türkiye will be exporting fossil gas to a European country that is not its neighbour (Gavin, 2024). While European negotiators have been open to continuing talks with Türkiye about establishing a fossil gas hub even after the collapse of talks on Türkiye’s accession to the EU, continued investments in fossil gas are out of sync with European standards as the continent seeks to transition away from fossil fuels (Siccardi, 2024).

Existing global fossil gas infrastructure already supplies the volumes of gas projected to meet global demand. Any addition therefore risks becoming a stranded asset (Climate Action Tracker, 2022). Aside from the risk of stranded assets connected to a fossil gas hub, expanding domestic gas consumption also runs counter to Türkiye’s Paris Agreement obligations. If Türkiye intends to achieve net zero by 2053, it needs to focus on decreasing the share of gas in the energy mix, shelving plans to expand oil and gas production, and instead direct investments towards deploying renewables (Güllü et al., 2023).

Renewables

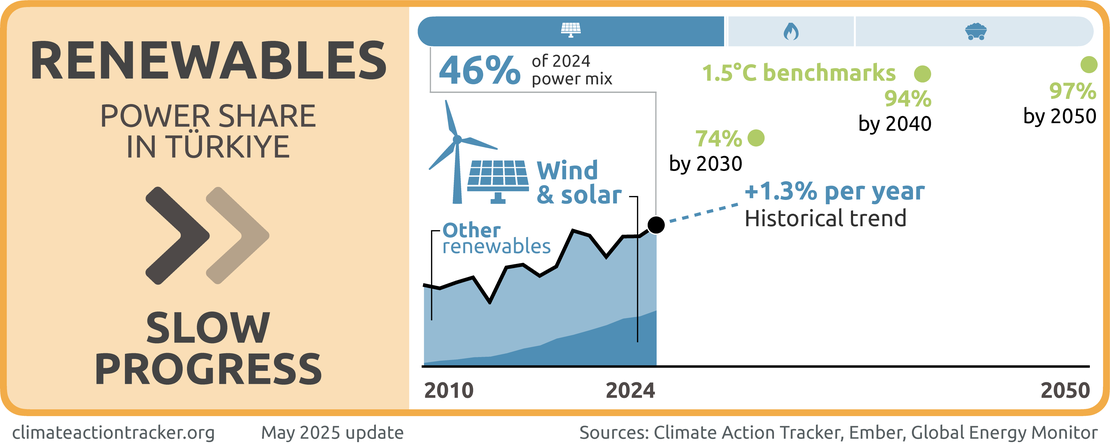

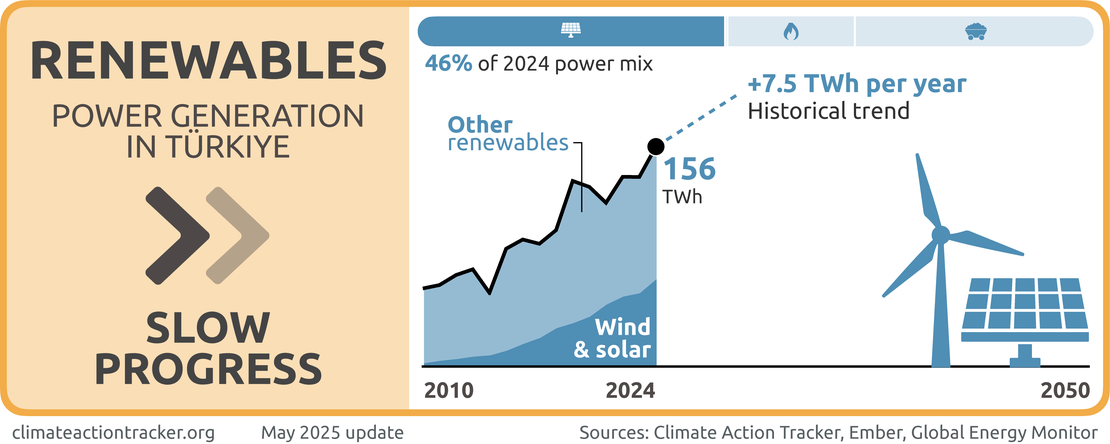

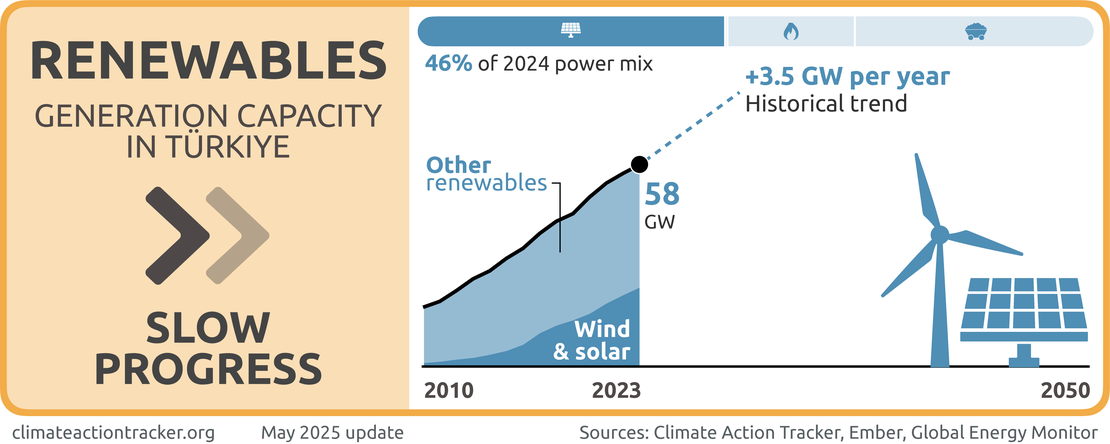

Wind and solar made up 18% of Türkiye’s total electricity generation in 2024. Türkiye aims to quadruple wind and solar capacity to 120 GW in 2035, which would make up 49% of total generation. While this is commendable, it falls short of what is needed for 1.5ºC. A 1.5°C compatible Turkish power sector would see wind and solar capacity reach 150 GW by 2035, 30 GW more than its current 120 GW target (NewClimate Institute and Climate Analytics, 2024). We evaluate progress in this sector as “Slow progress.”

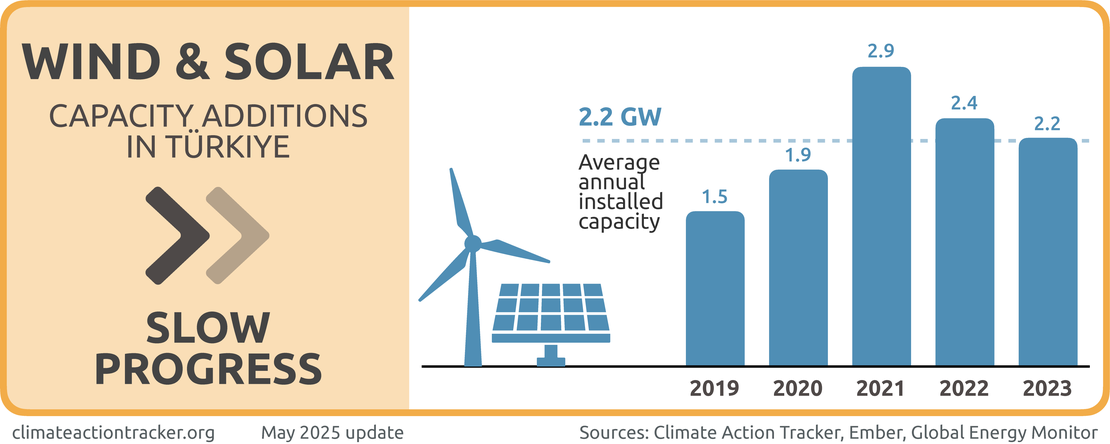

In 2023, Türkiye ranked eleventh in the world in terms of installed renewables capacity, with 59 GW of capacity already online (over half of which came from hydro) (IRENA, 2024; Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, 2024a). According to the recently-announced Roadmap for Renewable Energy to 2035, Türkiye intends to increase its total wind and solar capacity to 120 GW by 2035, compared to a current capacity of about 67 GW in 2024 (Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, 2024c; Ember, 2025). This will involve bringing at least 7.5–8 GW of wind and solar online every year until 2035, a significant increase on its previous goal of 5 GW of annual additions (Kazanci, 2024; Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, 2024a).

Türkiye’s increased ambition must also be matched by increased implementation. Since the National Energy Plan was released in 2022, the country has struggled to meet the annual targets. In 2023, 2 GW of solar and just 411 MW of wind capacity were added – the lowest annual rollout for wind power in 13 years (Ember, 2024). Considering Türkiye’s heavy investments in fossil fuels, missing its renewables targets is hard to justify, particularly given the strategic importance of increasing energy independence.

To speed up the rollout, Türkiye aims to reduce permitting times for new projects from 48 months to less than two years (Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, 2024c). As the private sector is expected to cover the bulk of the costs for the renewable energy transition (Climate Investment Funds, 2024), faster returns on investments should in turn stimulate more investment. A more competition-based model will be encouraged using tenders, and the government will hold a tender for 2 GW of wind and solar each year (Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, 2024c). Regulatory adjustments which offer a floor price and long-term electricity purchase guarantees to investors aim to improve investment conditions for renewable projects (EnergyNews, 2024).

USD 108bn of public and private investment will be needed to achieve the target, of which USD 28bn will go towards upgrading the transmission infrastructure (EnergyNews, 2024). This is designed to expand the transmission system in order to improve interconnectivity for the introduction of greater renewable capacity (Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, 2024a; Spasić, 2023).

Nuclear

Efforts to meet growing energy demand while reducing dependency on fossil fuel imports have seen Türkiye include nuclear power in its energy portfolio (Gesellschaft für Anlagen- und Reaktorsicherheit, 2023). With support from Russia, Türkiye’s first nuclear power plant, the Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant, was expected to begin supplying energy in 2025, but due to delays will not be fully operational before 2028 (Maddela, 2025). Türkiye aims to bring 7.2 GW of nuclear capacity online by 2035, which would account for 4% of electricity supply (Turkish Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, 2022).

A second proposed nuclear power plant in the northern city of Sinop has been in the works since 2013, when Türkiye signed an agreement with Japan (Enerdata, 2020). However, in 2020 the partnership to build the 4.5 GW nuclear power plant fell apart (Hürriyet Daily News, 2020). The Ministry of Environment and Urbanisation has given a positive environmental impact assessment (EIA) to the Sinop project, but the government is still seeking project partners (Shaw, 2024). Türkiye is also in advanced negotiations with China to build another nuclear power plant in Thrace, near the Greek border (Nuclear Business Platform, 2024).

Although nuclear electricity generation does not emit CO2, the CAT does not see nuclear as the solution to the climate crisis due to its risks such as nuclear accidents and proliferation, high and increasing costs compared to alternatives such as renewables, long construction times, incompatibility with flexible supply of electricity from wind and solar, its vulnerability to heat waves, and security issues.

While nuclear power can reduce the emissions intensity of the Turkish power system, there are also fears around the potential impact of earthquakes in the region (Hadjicostis & Mcdermott, 2023). There has been considerable opposition towards nuclear energy as a result, with safety considerations around seismic activity a concern for local communities (Temocin, 2018). The uncertainties and risks around nuclear construction make the technology unreliable in terms of planning the necessary power system decarbonisation, which needs to happen globally by 2050.

Industry

Türkiye’s industry sector accounts for 24% of total emissions (excl. LULUCF) (Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, 2023; Republic of Türkiye, 2024). This share is split between industrial processes (12%) and energy use (12%). The manufacturing industry alone represents over a fifth of Turkish GDP (Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Environment Urbanisation and Climate Change, 2024), so decoupling economic growth from emissions is critical to placing Turkish industry and the broader economy on the path to net zero.

Cement, iron, and steel production account for most of Türkiye’s process-related emissions (Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Environment Urbanisation and Climate Change, 2024). These industries will be impacted by the EU’s Carbon Adjustment Border Mechanism (CBAM), which will be fully introduced in 2026 (European Commission, 2024). CBAM places a carbon price on goods imported into the EU. Given that the EU represents an important trading partner for Türkiye, decarbonising the industrial sector will be essential to maintaining industrial competitiveness.

With the passage of its new Climate Law in July 2025, Türkiye has formalised the launch of an Emissions Trading System (ETS) modelled after the EU’s ETS) (Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Environment Urbanisation and Climate Change, 2024). This is a market mechanism which caps how much GHGs a company can emit, with the cap gradually declining over time. The pilot phase of Türkiye’s ETS will begin sometime in 2026, with all necessary plans and secondary legislation to be ready by 2027 (ICAP, 2025).

The specific sectors and gases to be covered, as well as exact details on the emissions thresholds, will be defined in secondary legislation and are not yet known. However, the Turkish ETS is expected to have coverage similar to the EU ETS and leaves the door open for Türkiye to adopt its own CBAM for imported goods (ICAP, 2025).

Agriculture

Agricultural emissions account for about 13% of Türkiye’s total emissions (excl. LULUCF), with the main sources being methane emissions from enteric fermentation in livestock and nitrous oxide emissions from organic decomposition in soil (Republic of Türkiye, 2024). Agricultural emissions have been steadily climbing over the last several decades and were 38% higher in 2024 than 1990 levels.

60% of Türkiye’s methane emissions come from the agricultural sector (İklim Değişikliği Başkanliği [Climate Change Directorate], 2024). In its Long Term Climate Strategy, the government lays out four key priorities for reducing emissions from agriculture: improved management of soil and water, adoption of climate-smart agriculture practices, improved management of agricultural residue, and increased education in the form of skills training (İklim Değişikliği Başkanliği [Climate Change Directorate], 2024). However, the government has not yet implemented policies to meaningfully decarbonise this sector.

Transport

Transport emissions account for around 16% of Türkiye’s total emissions (excl. LULUCF) (Republic of Türkiye, 2024). The largest share of emissions comes from road transportation, which more than tripled between 1990 and 2021 (Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, 2023).

In line with increasing road transport emissions, the number of vehicles on Turkish roads has almost tripled since 1990 (Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Environment Urbanisation and Climate Change, 2024). Nevertheless, there are 161 motor vehicles per 1000 inhabitants in Türkiye, which is far less than in developed countries (Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Environment Urbanisation and Climate Change, 2024). In the EU, for instance, this figure is 560 per 1000 inhabitants (Eurostat, 2024).

Turkish transport policy is therefore at a crossroads. As the economy continues to grow, so too will vehicle ownership. Putting in place incentives and infrastructure designed to increase electric vehicle (EV) uptake will allow Türkiye to expand vehicle ownership sustainably without increasing emissions. Türkiye aims to place EVs at the heart of industrial policy through the manufacturing of its first domestically produced EV, the Togg (Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Industry and Technology, 2022).

Türkiye adopted the COP26 declaration on accelerating the transition to 100% zero emission cars and vans but has yet to introduce policy at the national level with a commitment to expand the market share of zero emission vehicles to 100% by 2040. However, Türkiye does aim to increase the market share of EVs to 35% by 2030 (Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Industry and Technology, 2022) and has made significant progress towards this goal, with EVs reaching 21% of the market in August 2025 (Daily Sabah, 2025).

Its domestic EV production gives it an advantage in terms of meeting the goals of the COP26 declaration, and Togg sales have already driven a substantial increase in EV sales in Türkiye (Kasapovic & Knowles, 2024). In July 2024, the Turkish government passed a USD 5bn package to boost annual EV production to one million vehicles (Reuters, 2024). A stronger target that implements its COP26 commitment can set Türkiye on a path toward 100% zero emission sales by 2040.

Rolling out EV infrastructure is critical to supporting their uptake. The government aims to establish a fast-charging network by providing grant support to private sector actors (Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Environment Urbanisation and Climate Change, 2023), as well as supporting drivers’ access to public charging stations at a regulated price (Kaya, 2022). However, EV infrastructure is not being rolled out fast enough. There are 12.5 EVs per charging point in Türkiye. In contrast, there are 3-to-1 in the Netherlands and Belgium, and about 6-to-1 in Italy (Hürriyet Daily News, 2024).

A modal shift towards rail will form an important aspect of reducing emissions in line with 1.5°C. Türkiye aims to increase the share of freight transport by rail to 20% by 2035 and the share of passenger transport by rail to 5% by 2035, up from 2019 levels of 0.9% and 3%, respectively (Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Environment Urbanisation and Climate Change, 2023). Ongoing measures to achieve this include significant investments in modernising its rolling stock and constructing new lines between major cities (Railway Gazette International, 2024; Railway Supply, 2024).

Türkiye also aims to become a producer of high-speed electric trains, which it can use domestically as well as export. Similar to its approach with the Togg, Türkiye sees domestic manufacturing of electric trains as a way to blend industrial policy with environmental goals.

Waste

Waste emissions account for around 3% of Türkiye’s total emissions, representing a small and relatively stable source of greenhouse gases since 1990 (Republic of Türkiye, 2024). The two main sources of waste emissions in Türkiye are solid waste disposal and the treatment and discharge of wastewater, both of which produce significant amounts of methane.

Türkiye’s main programme to reduce emissions in the waste sector is the “Zero Waste Policy,” which launched in 2017 and aimed to increase recycling rates to 35% by 2023 (EEA, 2025). Unfortunately, Türkiye has seen a significant increase in waste generation over the last decade, with landfill rates remaining high while efforts to boost recycling have struggled.

Türkiye does not currently impose pretreatment requirements or bans on landfilling or incineration of waste (EEA, 2025). To reduce emissions in the waste sector, Türkiye should consider enacting policies such as these that aim to reduce the amount of methane generated during the waste cycle.

Türkiye had a small LULUCF sink of 56 MtCO2 in 2022, compared to a total emissions level of 502 MtCO2 (incl. LULUCF) (Republic of Türkiye, 2024). The sink is diminishing, however, due in large part to the government’s increase in wood production (Climate Transparency, 2022). Türkiye has also suffered from increasingly severe wildfires in recent years, which show no signs of stopping in a warming world (Global Forest Watch, 2023).

Türkiye was successful in meeting its target of increasing its forest land to cover 30% by 2023 (Kübra Ağaçyetiştiren, 2024; Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Environment Urbanisation and Climate Change, 2024).

Türkiye signed the forestry pledge at COP26. The updated NDC does not specifically mention the declaration; however, the main mitigation policies in the LULUCF section do aim to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030.

Methane

Methane is responsible for around 16% of Turkiye’s emissions and comes predominantly from agriculture and waste (Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Environment Urbanisation and Climate Change, 2023). Türkiye has not signed the Global Methane Pledge.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter