Policies & action

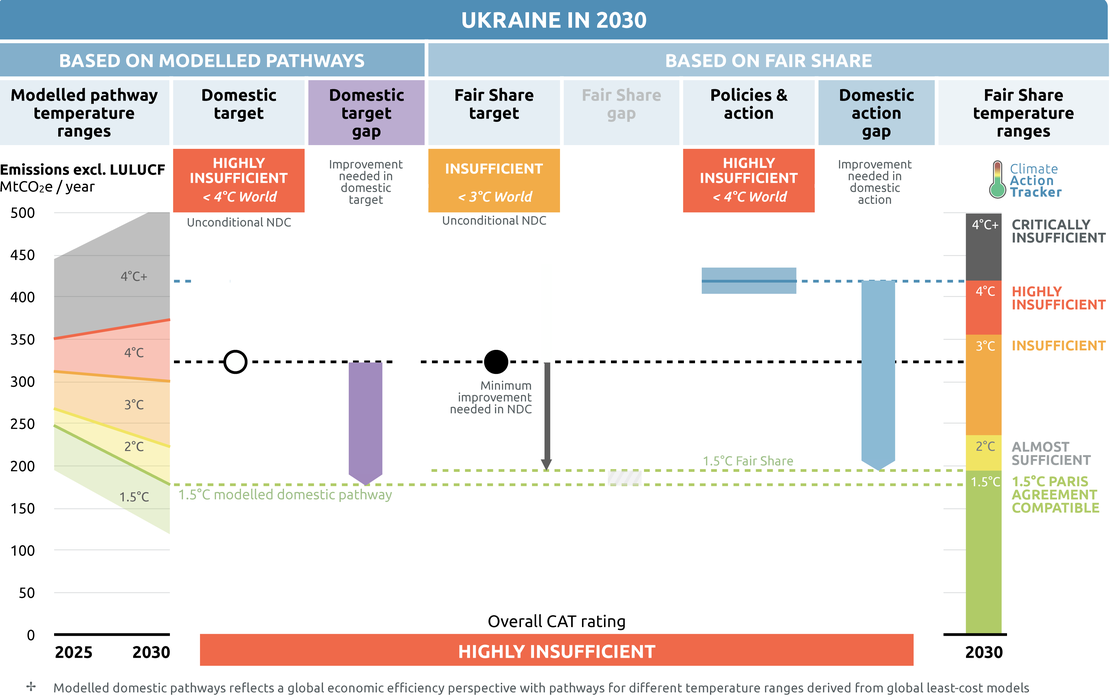

We rate Ukraine’s policies and actions as “Highly insufficient”. The “Highly insufficient” rating indicates that Ukraine’s policies and action in 2030 lead to rising, rather than falling, emissions and are not at all consistent with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C temperature limit. If all countries were to follow Ukraine’s approach, warming could reach over 3°C and up to 4°C. Planned policies would let emissions stabilise roughly at today’s level and rate “Insufficient”.

Note: the assessment below has not been updated and shows the status of the last update (30 July 2020).

Policy overview

Between 1990 and 2000, emissions in Ukraine dropped by 55% from 942 MtCO2e to 427 MtCO2e excl. LULUCF. From 2001 to 2007, emissions started to increase again moderately, followed by a steep decline during the financial crisis in 2009 and further declines in recent years as a result of the conflict in Eastern Ukraine. Between 2017 and 2018, emissions increased by 5% to 339 MtCO2e.

Currently implemented policies and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic are expected to lead to an emissions level of 333-334 MtCO2e excl. LULUCF in 2020 and 403-434 MtCO2e excl. LULUCF in 2030.

The COVID-19 pandemic has severely impacted Ukraine, currently leading to lower greenhouse gas emissions and accelerating the country’s energy crisis which had slowly been building for years. The quarantine measures slowed down the country’s economic activity, and GDP is expected to drop by 8.2% in 2020 (IMF, 2020). Both energy demand and production are decreasing and the power sector payment regime is on the verge of collapse, in the worst case leading to a severe power crisis (Prokip, 2020).

In May 2020, the Ukrainian government approved the Economic Stimulus Program to help stabilise the economy in light of the COVID-19 pandemic (Government of Ukraine, 2020a). The programme includes a number of short and medium-term measures for supporting Ukraine's economy for the period of 2020-2022. While the document mentions optimising the environmental tax to promote eco-friendly modernisations, links to climate and environmental policy are limited (Government of Ukraine, 2020a).

Environmental NGOs argue that money from the economic stimulus funds could be used for restructuring the coal industry to save mining jobs (350.org Ukraine, 2020; Zasiadko, 2020). The Ukrainian government should take into consideration that if low carbon development strategies and policies are not rolled out in the economic stimulus package, emissions could rebound and even overshoot previously projected levels by 2030, despite lower economic growth (Climate Action Tracker, 2020).

Following Ukraine’s national elections in July 2019, Oleksiy Orzhel, former head of the Ukrainian Association of Renewable Energy, was appointed Minister of the newly established Ministry of Energy and Environmental Protection, which sent a positive signal (Chemnik, 2019; Government of Ukraine, 2019). In March 2020 however, more than two-thirds of the Cabinet of Ministers, including Orzhel and the Prime Minister, were dismissed. The changes in government, followed by the COVID-19 pandemic have left the Ministry with an interim minister and no clear policy direction for the energy sector (Krynytskyi & Savytksyi, 2020).

In 2019, the Ministry had laid out priority areas for the near future, including a "significant" increase in imports of gas via Poland and a renewed focus on energy efficiency and renewable energy to reduce the demand for gas in power generation (Elliot, 2019). Ukraine is also looking to attract international investments for untapping natural gas reserves in its onshore blocks and in the Black Sea. While locally-produced gas would lower Ukraine’s dependence on Russia, the country should rather focus on increasing its renewable energy generation to move towards a Paris-compatible pathway and avoid technology lock-in. The constant cost reduction of renewables and the development of battery and hydrogen technologies will also lead to the disruption of business models for gas-fired power plants in the longer term, potentially resulting in higher electricity costs for customers if Ukraine were to invest in new natural gas projects (Krynytskyi & Savytksyi, 2020).

In January 2020, the Ministry of Energy and Environmental Protection published Ukraine’s 2050 Green Energy Transition Concept (Ukraine Green Deal) and presented it to EU officials as a commitment of Ukraine to meet the objectives of the European Green Deal (Ministry of Energy and Environmental Protection Ukraine, 2020; Mitsovych et al., 2020). It is the first Ukrainian strategy document that integrates climate and energy policy and that is based on the long-term energy system model that was developed for the second NDC currently under preparation (Mitsovych et al., 2020). To become effective, the concept will still need to be supported by concrete policy measures through the National Energy and Climate Plan, which is expected to be completed in the second half of 2020. Therefore, we have not yet quantified its impact in our projections.

Overall, the concept focuses on reducing GHG emissions through improving energy efficiency and boosting the deployment of renewable energy. While this is a step in the right direction, the 2050 phase-out date for coal is disappointing and under the current plan, Ukraine will only achieve carbon-neutrality in 2070 (Morgan, 2020). In Paris Agreement-compatible pathways for Eastern Europe and Former Soviet Union countries, coal power generation would need to be reduced by 86% by 2030 below 2010 levels, leading to a phase-out by 2031 (Yanguas Parra et al., 2019). The Green Energy Transition Concept further sets a 70% target for renewable energy by 2050, while modelling done in 2017 showed that Ukraine could reach a 91% renewable share by the same date (Diachuk et al., 2017; Morgan, 2020).

In July 2018, Ukraine published its 2050 Low Emission Development Strategy. This strategy provides emission reduction pathways for the energy and industry sectors based on four scenarios containing different ambition levels of decarbonisation measures and policies. If the strategy and additional measures for the agriculture and waste sectors were fully implemented, Ukraine could significantly overachieve its NDC target with emission levels of 21% to 42% below the 2030 target. The Ministry of Energy and Environmental Protection indicated that an update of the strategy together with Ukraine’s Green Deal, newly published in January 2020, might replace the current Energy Strategy of Ukraine 2035 (Mitsovych et al., 2020)

Since 2011, Ukraine has a carbon tax that applies to CO2 emissions from stationary sources in the industry, power, and buildings sectors. In November 2018, the Ukrainian parliament decided to steadily increase the carbon tax rate (currently 0.02 USD/tCO2) from January 2019 onwards. But even with this increase the rate remains below 1USD/tCO2 in 2020 and still is the lowest carbon price in the world (Ministry of Finance of Ukraine, 2018; World Bank Group and Ecofys, 2018). New instruments for the taxation of carbon emissions are currently being discussed by the Ukrainian government, with one of the options being fuel-based taxation, i.e. taxing primary energy production and imports (Mitsovych et al., 2020).

Energy supply

The energy supply sector is responsible for 67% of Ukraine’s total emissions excluding LULUCF.

In 2017, Ukraine updated its energy strategy through to 2035 (Government of Ukraine, 2017a). The strategy sets new targets for electricity generation from different energy carriers. Although hydropower dominates the country’s renewable capacity (averaging 4.6GW), wind, solar and bioenergy capacity increased by 54% to 2.1GW in 2018, with an additional 4.6GW of capacity in the pipeline (KPMG Ukraine, 2019).

In 2019, the installed capacity of renewable energy excluding hydropower tripled within one year from around 2.1GW at the end of 2018 to 6.4GW at the end of 2019 (Mitsovych et al., 2020). In 2035, 25% of electricity generation is projected to come from renewable energy sources including hydropower (2015: 4%), 25% from nuclear power (2015: 26%), and 50% from coal, natural gas and oil products (2015: 70%) (KPMG Ukraine, 2019). However, a step-by-step implementation plan has not yet been developed. As there are no clear supporting policies tabled or discussed, except the feed-in tariff and auction mechanisms, we have not further quantified the energy strategy.

With regard to renewable electricity support schemes, Ukraine has a feed-in-scheme with fixed prices, called the "green" tariff for electricity, since 2008. The green tariff also guarantees grid connectivity to all renewable power generated from the project. The feed-in tariffs (FiT) were initially established at relatively high rates: 0.47 USD/kWh for rooftop solar PV under 100 kW and 0.12 USD/kWh for wind projects with capacity greater than 2 MW (International Energy Agency, 2017). The tariffs were updated in 2012, 2015, and 2017 and adjusted to market levels. The International Energy Agency (2017a) reports FiT rates of 0.18 USD/kWh for roof-top solar and 0.11 USD/kWh for large wind projects (greater than 30 kW capacity).

Due to concerns about the financial sustainability of the existing support scheme, a law introducing a new scheme based on competitive capacity auctions for renewables was signed into law in May 2019 (Mykhailenko et al., 2019; Savitsky, 2018). However, it is still unclear when the first auctions will be held (Mitsovych et al., 2020). Investors could still secure the “green tariff” if their projects have obtained land use rights, a grid connection agreement, a construction permit and a power purchase agreement (PPA) by 31 December 2019 (KPMG Ukraine, 2019). The tariff was very successful and in 2019 alone, national power companies, foreign and Ukrainian investors poured $4.5 billion USD into building wind and solar power stations to take advantage of the generous tariff (Prokip, 2020). However, the government had only budgeted to buy roughly half of the renewable power that companies are likely to produce this year and, as of March 2020, the government has put payments on hold and is trying to retroactively reduce the “green tariffs”, which would cause significant corporate losses, putting the whole renewable energy industry at risk (Kossov, 2020; Prokip, 2020).

On the measures related to electricity markets, Ukraine opened its electricity wholesale market in July 2019. Market regulations continue to adjust financial flows in the system, requiring the big energy companies to provide more electricity at low prices to the Guaranteed Buyer (GB) so that the GB can use increased profits to finance renewable support costs from the transmission tariff (Mykhailenko & Temel, 2019). Ukraine was, however, neither technically nor legally prepared for the new electricity market and in June 2020 interim Minister of Energy, Olga Buslavets, reported that the GB was roughly half a billion USD behind in payments to renewable electricity producers (Prokip, 2020).

Overall, Ukraine is facing a severe energy crisis, a crisis that has built up for years due to a lack of long-term energy policy planning, and accelerated by the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly putting the renewable energy industry as a whole at risk. In April 2020, the cumulative debt on the electricity market amounted to about $1.87 billion USD and roughly the same for the gas market (Prokip, 2020). In June 2020, the Ukrainian parliament has passed a bill (No. 2386) on the debt settlement in the electricity market but no decision has been reached on the gas market to date.

Meanwhile, the Cabinet of Ministers has signed a memorandum with renewable energy producers, which stipulates that RES producers accept the conditions for the voluntary restructuring of the green tariff. Tariffs for solar power and wind power facilities are expected to be retroactively cut by 15% and 7.5%, respectively, for plants commissioned in the period 2015-2019 and by 2.5% for solar and wind power plants commissioned from January 2020 (Government of Ukraine, 2020b). Ukrainian authorities committed to taking every measure to ensure the timely payment to the Guaranteed Buyer and the repayment of debts to RES producers who have agreed on the terms of the restructuring (Government of Ukraine, 2020b).

The integration of the power transmissions system with the EU is under development. In April 2018, the national transmission system operator Ukrenergo announced—following an earlier announcement in June 2017 on full integration with the European Network of Transmission System Operators Electricity (ENTSO-E) by 2025—the support of full-scale deployment of renewables in Ukraine and investments in grid modernisation (Savitsky, 2018).

Ukraine’s Electricity Market Law of June 2017 aims at aligning Ukraine’s national legislation with the regulation from the European Union’s Third Energy Package on the European gas and electricity markets through which Ukraine’s national electricity market will be liberalised (Government of Ukraine, 2017b; IEA, 2017). This includes separating companies according to distribution and transmission of electricity (Kiyv Post, 2017).

Industry

The industry sector is responsible for 17% of Ukraine’s total emissions excluding LULUCF. However, a significant part of the emissions in the energy sector are also related to industry. In January 2018 Ukraine’s environment ministry published a draft law that will require big emitters to audit their emissions as an initial step towards Ukraine developing a functioning Emission Trading System (ETS), initially by 2020 but in June the process was still ongoing (Carbon Pulse, 2018; ICAP, 2020). The draft law contains no information on the emissions threshold for installations, but sets out plans for a government registry, third party verification, and a process for companies to devise emissions monitoring plans. As this policy is still under development, we have not taken it into account in our analysis. Industrial production decreased in the last quarter of 2019, leading to a drop in energy demand by early 2020 and resulting in the suspension of operations at the biggest Ukrainian private coal mine in April 2020 (Prokip, 2020). The COVID-19 quarantine measures slowed down activity even further.

Transport

The transport sector is responsible for 15% of Ukraine’s total emissions excluding LULUCF. The 2030 National Transport Strategy of Ukraine sets a target of 60% emission reduction from 1990, although the sector had already achieved a 69% reduction in 2017. While the import of electric vehicles is exempt from VAT and the excise duties until 2022, as of 2015 both the first vehicle registration and environmental tax on emissions from cars have been abolished (Center for Environmental Initiatives, 2020; Ministry of Finance of Ukraine, 2018).

Buildings

In 2017, the residential buildings sector was responsible for 30% of Ukraine’s total final electricity consumption (IEA,2020). In January 2020, the cabinet of ministers approved a concept on energy efficiency in buildings and zero-energy consumption buildings along with a national action plan on these issues (Mitsovych et al., 2020).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter