Country summary

Overview

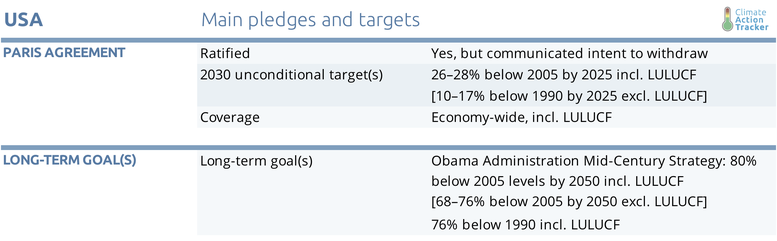

On 4 November 2019, the Trump Administration formally notified the United Nations that the US would withdraw from the Paris Agreement. This was the first possible day that the US could issue such a notification under the Agreement’s rules. This move puts the world’s second-largest emitter at odds with the rest of the world. The US exit will take effect exactly one year later, one day after the 2020 US Presidential Elections. It would leave the US as one of a handful of countries outside the Paris Agreement.

Domestically, the Trump Administration has continued with its campaign to systematically walk back US federal climate policy. Despite President Trump’s stated intentions to revive the coal industry, market forces of cheaper renewables and gas are leading to a fast decline of coal-fired power and the rise of renewables. Indeed, even though the EPA has weakened the Clean Power Plan (CPP), the US power sector still looks set to overachieve the Plan’s emission reduction goals.

Along with its weakening of the CPP, in the last six months, the Administration has also relaxed requirements for more energy-efficient lightbulbs, proposed freezing vehicle efficiency standards after 2020, and proposed allowing methane leaks from oil and gas production to continue for longer before they are found and fixed.

The government also adopted a rule that would revoke California’s authority to set its own emissions standards for cars and trucks that exceed the federal ones. This authority has allowed California to implement stricter programmes that aim to decarbonise the transport sector, including its Zero Emission Vehicle (ZEV) Program. Thirteen other states and the District of Columbia have adopted California’s tighter standards.

Blocking California and other states from implementing stricter state-level standards and the plans to weaken automobile emissions standards nationwide are a major step backward in addressing the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the US. California and another other 22 states, of which 13 have adopted California’s standards, have filed multiple lawsuits to stop the government from revoking states’ abilities to set stricter emission standards.

These actions build on more than 50 rollbacks that began in 2018 when the Administration passed a rule to ignore new regulations limiting highly potent hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) emissions, proposed weakening emissions standards for new coal-fired power plants, and instructed government agencies to change their climate science methodology.

In 2018, the US overtook Russia and Saudi Arabia to become the world’s largest producer of crude oil. It is also the world’s largest producer of natural gas, and increased LNG exports by 53% in 2018. The steady upward trend continued during the first half of 2019, when average net exports of natural gas more than doubled compared to average levels in 2018. With this significant increase, in 2019 the US became the world’s third-largest LNG exporter, behind Australia and Qatar. Globally, the power sector needs to decarbonise by 2050 to stay within the Paris Agreement’s long-term temperature goal; gas is not a long-term solution to deep decarbonisation.

At the subnational level, some cities, states, businesses, and other organisations are taking action. Recent analysis suggests that if recorded and quantified non-state and subnational targets were fully implemented, these measures could come within striking distance of the US Paris Agreement commitment, resulting in emissions that are 17–24% below 2005 levels in 2025 (incl. LULUCF). In total, 22 states, 550 cities, and 900 companies with operations in the US have made climate commitments, and all 50 states have some type of policy that could bring about emissions reduction.

The CAT’s US emissions projections for 2030 increased by 2-3% from our previous projections in September 2019, mainly due to the quantification of implemented rollbacks and new, higher, non-CO2 emissions projections data. On the CAT rating scale, we would rate US current policies as “Highly insufficient”. The US is within striking distance of the upper end of its 2020 target, with emissions projections for 2020 just 2–3% higher than the target.

The CAT would rate the existing US target under the Paris Agreement “Insufficient”, as it is not stringent enough to limit warming to 2°C, let alone 1.5˚C. However, given the Trump Administration’s decision to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, which nullifies the target, we rate the US “Critically insufficient.”

*based on CAT calculations

To meet its NDC target, the United States would have had to implement the Obama Administration’s Climate Action Plan, or equivalent measures. Current US policies are only projected to reduce emissions to 11–13% below 2005 levels (excl. LULUCF) by 2025.

Projected emissions in 2030 increased by 2-3% from our previous projections in September 2019. This is driven by updated projections of non-CO2 emissions and policy rollbacks that increase projected emissions in 2030 in non-power sectors:

- Increased emissions projections of non-CO2 gases (mainly methane and N2O),

- Increased emissions in the building sector due to the repeal of energy-efficiency requirements for lightbulbs, and

- Increased non-CO2 emissions due to the non-enforcement of the Significant New Alternatives Policy (SNAP) programme that would limit HFC gases emissions.

These have largely been offset by lower emissions in the electricity sector. The EIA’s Annual Energy Outlook 2019 (AEO) projects 8% lower emissions from electricity generation compared with 2018 (reference case), despite increased generation overall, with increased electricity generation from gas and renewables, and decreased generation from coal.

- Coal is projected to account for 22% of generation in 2030 (down from 26% in 2018),

- Gas: 38% (up from 34% in 2018),

- Renewables: 24% (up from 23% in 2018),

- Nuclear: ~15% (unchanged from 2018).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter